23rd January – 19th March 2016

The Old Vic, directed by Matthew Warchus

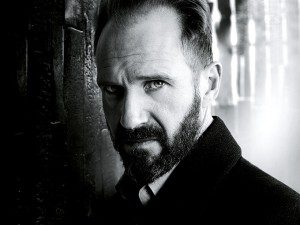

Ralph Fiennes as the Master Builder

London has form with Ibsen’s late great play Bygmester Solness. In 1893 a hundred Londoners were turned away from the world première. Over the preceding decade the English had come to like Ibsen very much, and were proud to be putting on this play (of the preceding year) before even the Norwegians. There was much discussion as to what it meant – a discussion which continues in newspaper reviews and undergraduate literature tutorials to this day. One of those to see the première was Henry James, who was impressed enough to write an article called ‘On the Occasion of The Master Builder’. Obviously, in his view, the ‘practised London’ actors had done a good job:

‘Not only has the battered Norseman had in the evening of his career the energy to fling yet again into the arena one of those bones of contention of which he has in an unequalled degree the secret of possessing himself, but practised London hands have been able to catch the mystic missile in its passage and are flourishing it, as they have flourished others, before our eyes.’

(Note to novices of James’s prose: it’s up to you whether you glory in the syntax – or forgive it for the sake of such phrases as ‘the battered Norseman in the evening of his career’). He goes on to describe Ibsen’s:

‘peculiar blessedness to actors. Their reasons for liking him it would not be easy to overstate; and surely if the public should ever completely renounce him players enamoured of their art will still be found ready to interpret him for that art’s sake to empty benches.’

James would be happy to know that a hundred and twenty-three years later the London public has emphatically not renounced Ibsen. Tickets to The Master Builder were hard to get. And according to the press, practised London hands have again caught the mystic missile in its passage and are flourishing it before our eyes: Time Out and The Observer give the production three stars, The Guardian, four and The Telegraph, five.

Certainly, Ralph Fiennes in the title role, despite giving a quiet performance in an enormous space, fills The Old Vic with his presence. Rob Howell’s opening set – a cross between a constructivist sculpture and a building site – is promising. But, on the whole, I felt this production to be a disappointment.

The main problem is the lack of passion. Fiennes is made to affect an old-man’s bandy-legged stoop, whereas he could and should have acted his own age. He is meant to be sexually magnetic – hence his young secretary Kaja’s obsession with him – but here he isn’t. He is at first utterly detached from what Hilde tells him took place between them a decade before, then is converted bizarrely quickly to the idea of it. An old man taking an easy way out is a far less moving spectacle than a man toppled by passion, desperation, or imagination (take your pick) at the peak of his career. It doesn’t help that Kaja is played by Charlie Cameron as an idiot child (either her bad acting or Matthew Warchus’s bad direction). David Hare’s adaptation of Ibsen’s text is prosaic and aims for laughs; the prose is never allowed to soar into creating castles in the sky.

There are deflating infelicities: the set turns red, with banal literalism, when the fire which consumes Aline’s ancestral house is recalled. A garden swing hangs around unused for most of the third act – only to swing into action when Hilde jumps on it to cheer on Solness as he climbs the tower from which he will fall. This isn’t a bad idea; it draws attention to the enormous set and its fly-tower in a way that stresses the connections between the building site and the theatre, between creating houses and creating plays, and between being Solness and being Ibsen. It also, like the three empty nurseries, seems like something kept for the absent children. But it is poorly used. Hilde doesn’t climb high enough to give a sense of ecstasy, and, once Solness has fallen, she should either carry on swinging herself with undiminished vigour (showing that she will live in the castle which his feat has constructed) – or she should suddenly stop swinging (indicating the reverse) – but she did something unfortunately inbetween.

Sarah Snook as Hilde Wangel on her swing

In other respects, the production makes clear choices between the various options permitted by the text in relation to Hilde Wangel. Her hiking dress, and what James observes to be her ‘curiously charmless name’, suggest robustness, whilst her feverish imagination suggests someone wraith-like, even consumptive. This production goes for robustness without a backwards glance. Sarah Snook has a ringingly-confident upper-class voice to match her physical strength (the former sitting oddly with her origin as a Norwegian village girl).

Sarah Snook as Hilde Wangel in hiking dress

Then there’s the question of whether Hilde is what E.M. Forster, in his essay ‘Ibsen the Romantic’, calls ‘a minx’ – or ‘a lure and an assessor’ through whom ‘from the moment she knocks at the door poetry filters into the play’. Forster thinks that she is both: ‘though her own voice may be that of a sadistic schoolgirl the sound has nevertheless gone out into the dramatist’s universe, the avalanches in Brand and When We Dead Awaken echo it’. Warchus, by contrast, opts for someone utterly sincere and without sadism, but equally lacking in poetry. She does not conjure up the splendour and theological challenge of the mountains which she loves to tramp – ‘the scenery of western and south-western Norway’ which Forster considers to be ‘The vehicle in which poetry reached’ Ibsen. She is somewhat too solid and prosaic to live in aerial castles; whilst Solness is a little too passionless and decrepit.

It is likely, therefore, that he falls passively rather than actively from the scaffolding; he doesn’t quite have the wherewithal to want to die at his supreme moment – and he leaves on the ground someone who will, one feels, somehow recover and live on. Meanwhile – for goodness sake let his poor wife Aline get out of her cursed house, not move in to the doubly-cursed new house which he has died inaugurating, move in with that nice inevitable Ibsenite Doctor (this time called Herdal), and finally get a life. Because one fears that Solness has nothing left of one now.

So this was a disappointment – given a stunning play and a great lead actor. 1893 was not too early for film; if only they had thought to film the world première.. Filming plays is something very obvious that humans have thought of doing amazingly late, like putting four wheels on suitcases. Had they done so, we might have learned a great deal about the Victorians – and ourselves – from the difference. But here, at least, is a photograph.

Elizabeth Robins who played Hilde Wangel in the 1893 London world première of The Master Builder