Philip McGinley as Blackmore and Anne-Marie Duff as Lizzie Holroyd

National Theatre: Dorfman, 21st October 2015 – 10th February 2016

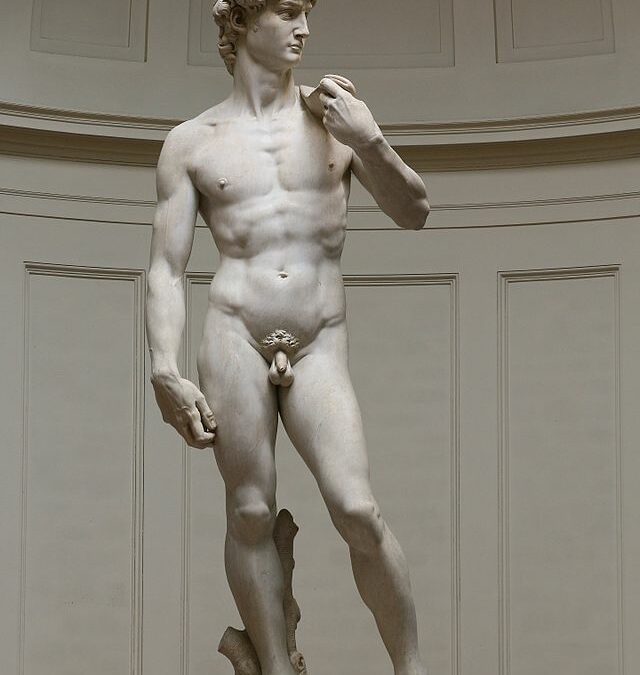

Husbands and Sons is not a play by D.H. Lawrence; it is a mash-up (hear that word in an Eastwood accent) of three of them: A Collier’s Friday Night (1909), The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd (1909-10) and The Daughter-in-Law (1913). Ben Power did the mashing up, feeling ‘the danger for an audience, if staged as a trilogy, of how potentially repetitive they could be.’ That – and Peter Gill did wildly successful productions of these three plus The Fight for Barbara (1913) in 1968 and, it would seem, he didn’t want to compete with those, one of which was a world premiere. 1968 was the giddy height of both the Lawrence craze and of kitchen-sink realism, which Lawrence had anticipated by half a century; of course those productions were a success. Nowadays Lawrence’s star is much lower. The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd was well-revived by the Orange Tree Theatre in the autumn of 2014, and RADA did a decent The Daughter-in-Law that February. But, it was presumably felt, these days a full Lawrence series would be just a bit too much. Hence the mash-up.

Or jigsaw, to use Power’s metaphor. He argues that the three plays’ pieces slot into each other; and he’s right. The plays’ families – the Lamberts, the Holroyds, and the Gascoignes – are all variants of Lawrence’s own; the wives are all more thoughtful, refined and ambitious than their men; the couples are all unhappy; the mothers all jealously guard their sons from their lovers, and run into conflict with their actual or potential daughters-in-law. The plays were all written and set at around the same time in Lawrence’s native Eastwood. So why shouldn’t these families be neighbours, as they are presented on the Dorfman’s stage-in-the-round? Why shouldn’t the action take place, as the programme has it, ‘Three weeks in October, 1911’ (it actually felt like one, very long, Colliers’ Friday night). Though the focus of the action is on one household at a time, at times the characters, moving between their houses, interact: Mr Lambert and Mr Holroyd bump into each other on their way home from the pub; he and Luther Gacoigne help to carry Mr Holroyd’s corpse to his wife. Tableaux underline the common themes: Lizzie Holroyd kisses her engineer whilst Ernest Lambert and his mother are joined in an alternatively-illicit embrace in the next house; Lizzie Holroyd reconciles with her husband only in death, whilst next door Minnie and Luther Gascoigne are reconciled after Minnie has lost her wealth. Michael Billington, in his review for The Guardian, complained that the Strindbergian flavour of The Daughter-in-Law, the Zolaesque tragedy of The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd, and the Sons and Lovers realism of A Collier’s Friday Night, are all lost as distinct flavours. So they are. Nonetheless – it works.

The simultaneity of the three houses’ actions is moving. We know that it is so – that if our houses lost their walls and only their ground-plans remained, as though painted on a stage, then the similarities and divergences of all our lives would become suddenly obvious. One family has a tragedy whilst the next one is having a reconciliation; c’est la vie. Except, in an early twentieth century mining community, the similarities, and the division of the men on the one hand and the women on the other, are especially striking. I was reminded of Khatyn – one of the hundred and eighty-five Belarussian villages which were burned along with their inhabitants during the Second World War. The memorial site preserves the villagers’ houses only as plans, with the family name – as on this stage – marked at ground level. One cannot walk round this site but speculate on how life was lived out by these neighbours, within earshot of one another, with similar occupations, and divergent fates – until the Einsatzgruppen arrived.

It was said of the 2011 BBC4 miniseries adaptation of Women in Love that it was feminist (even if nobody claimed the same of the 2015 BBC1 Lady Chatterley’s Lover). I would say that this play was feminist in exactly the way that the separate plays and Lawrence themselves were – intensely interested in women, and sensitively sympathetic to their wish to break out of the limitations of their circumstances, and the hardness of their lives with their men. At the time that he wrote them Lawrence was more interested in the women’s than the men’s side of the story, even though the men suffer too; and this shows in this production. The play’s title names the men, but as they exist in relation to the women. The poster nicely conflated both sexes, showing Mrs Holroyd’s face blackened like a miner’s; crucial to the play and these lives is the fact that the women don’t get their faces dirty.

Lloyd Hutchinson as Mr Lambert, Anne-Marie Duff as Lizzie Holroyd and Louise Brealey as Minnie Lambert were all excellent, but, alas, the cast as a whole was variable. Attempts at Eastwood accents varied not only between the actors (they can’t all have been right), but in individual actors across the course not only of the play, but a sentence, or even a word. This was irritating, and reminded one, in this ‘National’ theatre, that actors on London stages nowadays tend to be people to whom received pronunciation is native, and to whom all others need to be taught. In which case, for God’s sake let them learn it; isn’t that part of the actor’s craft, and aren’t these professionals?

No matter. This was a moving production of a well-conceived and well-constructed play, and a vindication of Lawrence’s strength as a playwright – even if most of the audience looked as though they might have been there at the Gill quartet of 1968, and therefore already converts. There is after all something right about Lawrence’s plays appearing in London. It was after moving to Croydon as a school-teacher in 1908 that he started visiting the theatre often, and directed a play by Yeats at his school. He may have discovered that his greatest talents lay in other genres; but it was also the case that his plays were ahead of their time, and that the London stage on which he had hoped to see them took fifty years to catch up. Since then, the life which they depict largely vanished, in the 1980s; it, no more than working-class realism, should be forgotten.