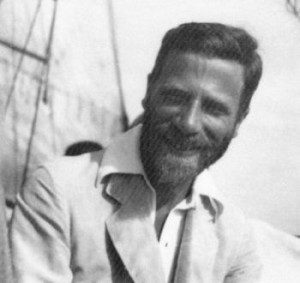

Theodore Stephanides, doctor, biologist, translator, poet, and mentor of Gerald Durrell

Sources in order of recency:

Conversation with my mother-in-law Alexia Mercouris née Stephanides

12th May 2016

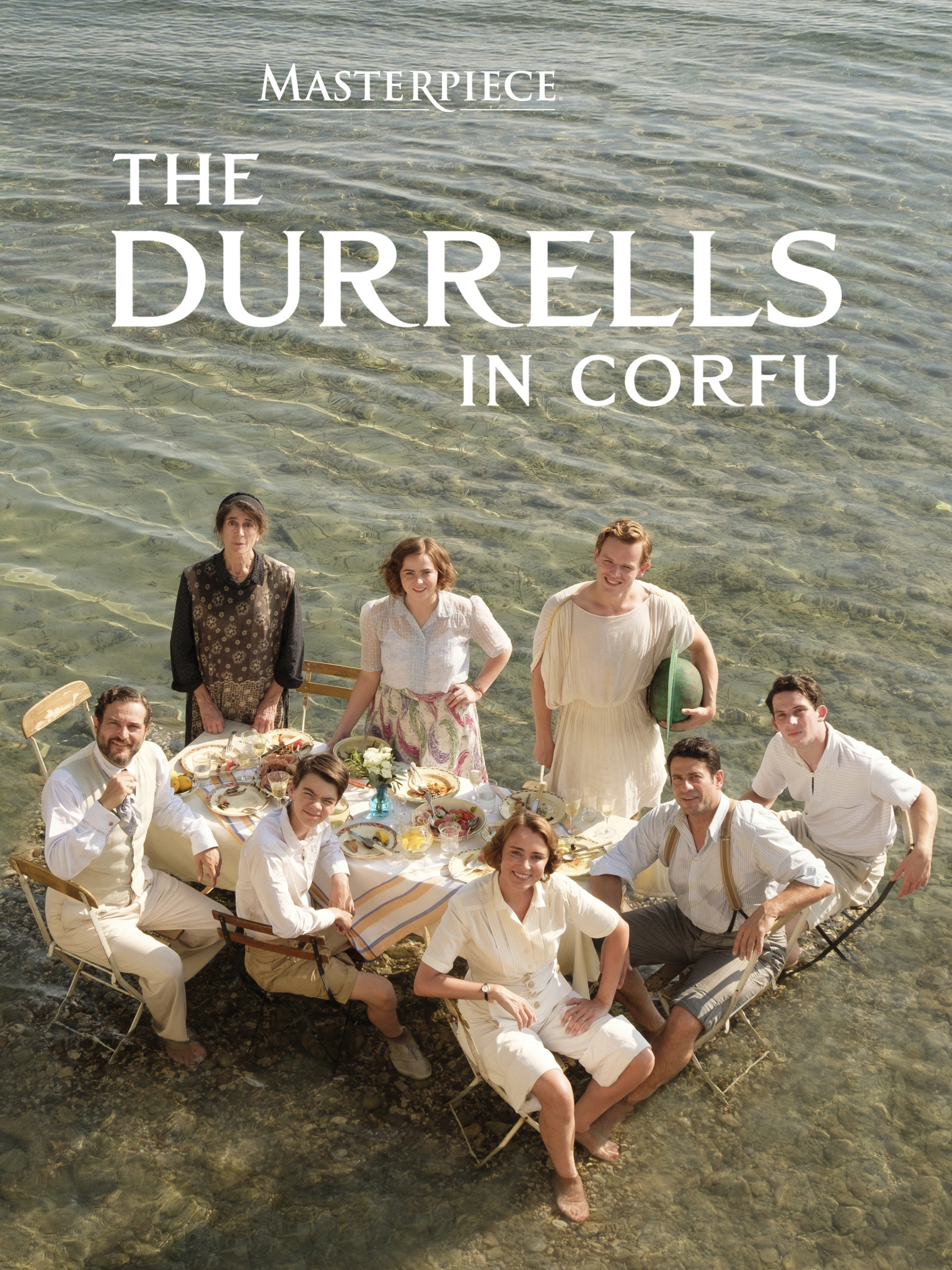

The Durrells

2016 ITV 6 part TV series, broadcast from 3rd April, written Simon Nye, directed Steve Barron and Roger Goldby

Autumn Gleanings: Corfu Memoirs and Poems

2011 (posthumous collection of memoirs) Theodore Stephanides

My Family and Other Animals

2005 BBC TV film, written Simon Nye, directed Sheree Folkson

My Family and Other Animals

1987 BBC 10 part TV series, written Charles Wood, directed Peter Barber-Fleming

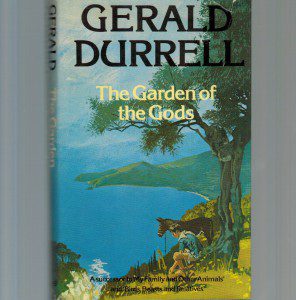

The Garden of the Gods

1978, Gerald Durrell

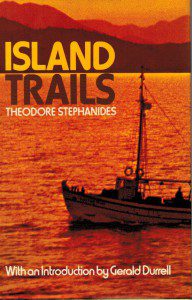

Island Trails

1973, Theodore Stephanides

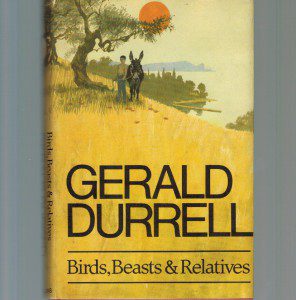

Birds, Beasts and Relatives

1969, Gerald Durrell

The Garden of the Gods

1967 BBC documentary with Gerald Durrell and Theodore Stephanides

My Family and Other Animals

1956, Gerald Durrell

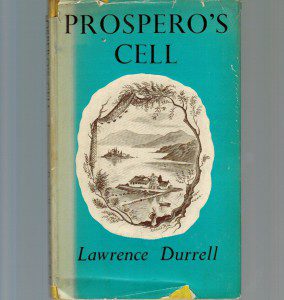

Prospero’s Cell: a guide to the landscape and manners of the island of Corcyra

1945, Lawrence Durrell

‘Why’, my Greek husband asked me today, ‘is anyone interested in the lives of an upper-middle class English family on Corfu?’

Certainly, it seems that lots of English people are. The BBC has adapted Gerald Durrell’s 1956 My Family and Other Animals (and its 1969 and 1978 successor volumes) twice, in 1987 and 2005. Now ITV has had a go, with a six-part series that prominently announces itself as ‘Series 1’, and which seems to have been popular enough to guarantee its successors.

‘Well’, I answered, ‘it has to do with the English relationship with Southern Europe’. And I started to extemporise on the differences between those English who were awakened to sex, life and suntan by, respectively, the South of France (probably more the upper and upper-middle classes, those who don’t like their abroad too far away or foreign, cultural Francophiles), Italy (the intelligentsia of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, D.H. Lawrence, E.M. Forster, the liberated young things that both describe, me), and Greece (the Classically-inclined, Turkophobes, Byron, colonial and military occupiers who had a nice time there, the Durrells, those who like the Durrells, Willy Russell, those who like Shirley Valentine, Louis de Bernières, those who like Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, and so on).

In these various Southern parts we English do native-bewildering things such as swim in the sea, lie in the sun, drink too much, or flog round ruins or mountains for pleasure. The Durrells and The Durrells, I tried to explain, have the appeal of these kind of experiences, lived for us by proxy by a comically-diverse family with whom we can variously identify, during the halcyon days before World War II destroyed much of Corfu, and mass tourism followed in its wake. They enable us both to acknowledge, and to gain a distance from, our Englishness, as Larry did when he described the remaining traces on Corfu of its English occupation of 1815-60:

‘The discreet picnics among the olive-groves, the memoranda, the protocols, the bustles, sidewhiskers, long top-boots, tea-cosies, mittens, rock-cakes, chutney, bolus, dignity, incompetence, book-keeping, virtue, church bazaars; you will find traces of all of them if you look deeply enough. The flash of red hunting coat through the olive-groves as the officers galloped over the island on their dangerous paper-chases; the declarations of love among the cypresses, the red-faced sportsmen setting out for Albania. Big Tom, Adams, Leech, and ‘Fusty’ Andrews; Lockler, Jones, and Jervis White-Jervis. Dr. Anstead fussily visiting these ‘embayed seas’ to record the lamentable venality of the islanders. Edward Lear’s gloomy pictures of Perama and the Hyallic Gulf.’

My husband still didn’t see it.

Purist fans of the Gerald Durrell trilogy may be irritated at the departures made by the recent television series from its template.

Like the other adaptations, it downplays the ‘other animals’ and plays up ‘my family’, on the understanding that most people do not belong to that botanically-obsessed minority that included Gerry and Theodore. Theodore giving his scientific explanations, as he is recorded as doing in the trilogy, and as he does himself in parts of his memoirs, would bore most viewers. So too, alas, might voiceover of Gerry’s breathtakingly beautiful descriptions of the nature with which he interacts – for example: ‘The sky looked as black and soft as a mole-skin covered with a delicate dew of stars. The magnolia tree loomed cast over the house, its branches full of white blooms, like a hundred miniature reflections of the moon, and their thick, sweet scent hung over the veranda languorously, the scent that was an enchantment luring you out into the mysterious, moonlit countryside’. Without either, one is left simply with close-up shots of flora and fauna. And so these are brief, and briefly glossed by Gerry, annoyingly played by Milo Parker. Let those who are interested in these things read the books, or, preferably, move to Corfu, and get a friendly local Professor to lend them a boat and crew for a grand botanical tour of the Greek islands, as Theodore Stephanides had the good fortune to have done for him in 1933.

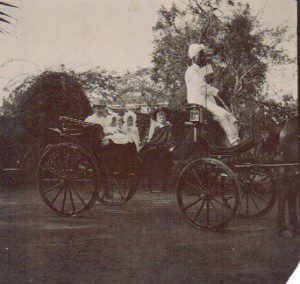

Another major departure from the trilogy and from fact was the use of English. More than the 2005 film, this adaptation used subtitles sparingly, and therefore gave the impression that most of the island’s peasants spoke English, and that the Durrells did not speak Greek. In fact, it was the other way around, the Durrell children learning Greek pretty fast. Even today I doubt that many rural Corfiots speak English as well as they do in this adaptation. But to have much Greek would have been a bit too estranging, too foreign, for the viewing public. On the other hand, Theodore Stephanides as played by Yorgos Karamihos is given a Greek accent, in a pardonable simplification of the fact that Theodore was born to a Greek family in the Raj (his father married a daughter of the merchant Ralli family) and brought up with upper-class English, only later learning to speak Greek at all.

Theodore Stephanides in Bombay in 1900

Theodore Stephanides in Bombay in 1901

But there were other, bolder departures from the trilogy. Mrs Durrell is animated from a placid matron into a vital, if harassed, woman ready for love; she has an invented love interest; Leslie gains and loses a Corfiot girlfriend; Larry has a visiting girlfriend; Theodore Stephanides is not a doctor (nor anything like the original, whom Christopher Godwin captured excellently in 1987); the island’s only doctor has an invented British wife; Margo works for the Countess; and so on. Many, though not all, of the incidents are invented.

But such irritation is, I think, rendered absurd by what Gerald did to his family in the first place. At the opening of the second book in the trilogy, Birds, Beasts and Relatives, he recalls the first meeting of the family in England ‘since the war’, at which ‘that bloody book of Gerry’s’ (My Family and Other Animals) is mentioned by Leslie. Larry expostulates: ‘You’ve no idea what damage that Dickens-like caricature did to my literary image.’ Leslie responds: ‘By the way he wrote about me, you would think that I never thought about anything but guns and boats’. Margo chips in: ‘I was the one that suffered most. He did nothing but talk about my acne’; and their Mother responds: ‘I thought it was quite an accurate picture of you all. But he made me out to be a positive imbecile’. The family is collectively appalled at Gerry’s sudden bright idea of writing a sequel, but, ‘Faced with such a firm and united family, bristling in their resolve to prevent me at all costs, there was only one thing I could do. I sat down and wrote this book.’ In this anecdote, and thereafter, the various family members are simplified in precisely the manner that they complain of.

One thing that The Durrells makes clear is that one just can’t flatten character quite as much on film as one can on a page. Just by virtue of being visible, and mutually interactive, the characters’ respective interests in something other than acne, hunting, art, cooking, or fauna becomes manifest. Gerry cut so much out (and he was, after all, writing the recollections, two decades after the fact, of a ten-to-fifteen-year-old) that the film-maker not only can but more or less has to take some liberty in deciding what to put back in.

And what has writer Simon Nye chosen? Sex or something in that direction for all the family apart from Gerald (though he too seems to have found a girlfriend during the closing knees-up of Episode 6). And this is fair enough. It is understandable that it was not the young Gerry’s main concern, but it is part of life – perhaps particularly for pale Englanders warmed by the Ionian sun; and so, why not? One can object that Mrs Durrell, from all one knows of her, had no such reawakening, and that Larry, had he had a girlfriend visiting during this period, would certainly not have had sex with her at the villa, nor kissed her in front of his relatives. These last are reprehensible anachronisms. But, liberty with the past though it was, the love interest for Mrs Durrell was sensitively drawn.

As for the made-up characters – they stand in place of the real ones who were excluded from the memoirs in the first place. For all concerned made striking exclusions. Gerald fails to mention Leslie’s wife Nancy, and the fact that the couple eventually moved away from the family into a villa of their own. He does not mention Theodore’s wife Mary, nor the latter’s daughter Alexia. Larry, in Prospero’s Cell, does not mention the rest of his family being on the island, gives one mention to Theodore’s wife, and none to Theodore’s daughter – despite the fact that, as Theodore recalls in the memoirs published as Autumn Gleanings, for some time Mary and Alexia lived in one half of a villa, whilst Larry and Nancy lived in the other. For his own part, Theodore does not mention Gerry at all in Autumn Gleanings, and in Island Trails gives him only one brief mention: ‘Other people besides Nikos were also interested in my doings. Among them was the ten-year-old Gerald Durrell, the younger brother of Lawrence […] I think that it was I who first inoculated Gerald with the natural-history virus. He often used to accompany me on my expeditions, returning home wet and muddy, but brimful of enthusiasm. This enthusiasm was not always shared by the rest of the family when they encountered the leeches and spiders and other interesting specimens which were continually escaping from custody and roaming about the house’ – that, and a few details in the couple of paragraphs which follow, is it. By contrast he stresses Larry’s interest in nature, of which Gerry’s memoirs make little mention. In all of these male memoirs, women (with the exception of Mother in Gerry’s) are marginalised, and the one girl in their lives gets cut almost entirely. This despite the fact that Alexia Stephanides would accompany her father and Gerry on their Thursday afternoon explorations of the island’s nature, and that a number of the incidents which are described as happening to Mrs Durrell happened in fact to her mother Mary Stephanides (née Alexander).

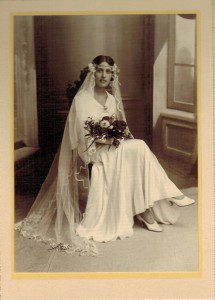

Mary Alexander (mother’s maiden name Moustoxides) on the day of her marriage to Theodore Stephanides in 1930

Theodore and Mary

Mary and Alexia

Theodore and Alexia

This is no doubt partly a reflection of the relative patriarchy of the then (1930s) and the there (Greece). Women were not only less present in narrative, but in social life. Larry, Theo, and other men do a great deal of socialising without their women folk. Gerald also explained to Alexia after the publication of his books that he had not wanted to cast the shadow of future divorces over his sunlit narrative (Larry and Nancy divorced, as did Theodore and Mary); though the remedy was pretty ruthless.

But if Alexia has been elided, her father most certainly has not.

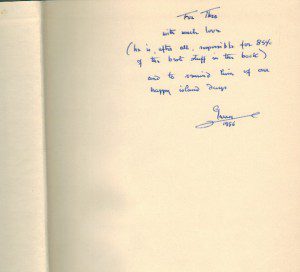

Our family copy of My Family And Other Animals is inscribed:

‘For Theo with much love (he is, after all, responsible for 85% of the best stuff in this book) and to remind him of our happy island days. Gerry 1956.’

Birds, Beasts and Relatives is inscribed:

‘for THEO a small tribute to a great man with love from Gerry’. The dedication is to ‘Theodore Stephanides in gratitude for laughter and for learning’

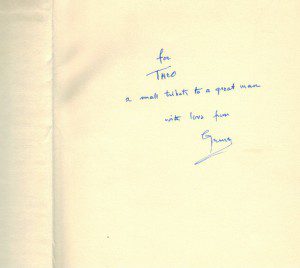

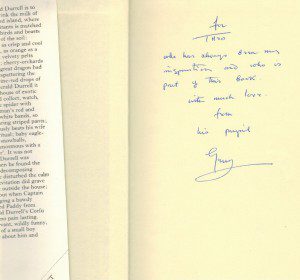

The Garden of the Gods is inscribed:

‘for THEO who has always been my inspiration and who is part of this book. With much love from his pupil Gerry’

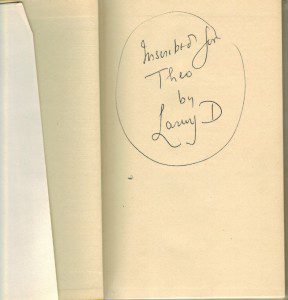

Prospero’s Cell is inscribed more reservedly:

‘Inscribed for Theo by Larry D’

but is dedicated thus: ‘Four of the characters in this book are real people and appear here by their own consent. To the four of them, Theodore Stephanides, Zarian, The Count D. and Max Nimiec it is dedicated by the author in love and admiration’

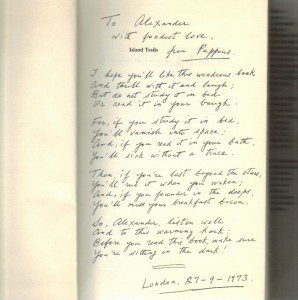

Finally in Island Trails my husband gets a look in. It is dedicated ‘To my two grandsons, Alexander and Pyrrhus, with fondest affection’, and is inscribed:

To Alexander with fondest love from Pappous.

I hope you’ll like this wondrous book

And thrill with it and laugh;

But do not study it in bed

Or read it in your baugh.

For, if you study it in bed,

You’ll vanish into space;

And, if you read it in your bath,

You’ll sink without a trace.

Then, if you’re lost beyond the stars,

You’ll see it when you waken;

And, if you founder in the deeps,

You’ll miss your breakfast bacon.

So, Alexander, listen well

And to this warning hark:

Before you read this book, make sure

You’re sitting in the dark!’

London 27-9-1973

Earlier that year his daughter and son-in-law had bought, with his money, the house in which Alexander and I now live. Aged seventy-seven, and twelve years retired as chief radiologist at St Thomas’s Hospital, he moved cordially back in with his ex-wife and their family, and wrote Island Trails – or wrote it up, from notes which he had made at various times before.

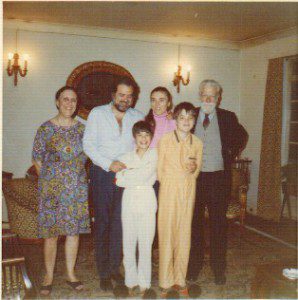

Mary Stephanides, Spyros Mercouris, Pyrrhus Mercouris, Alexia Mercouris, Alexander Mercouris, and Theodore Stephanides, in Bayswater just before moving to our current house

In that year, the dictatorship of the Colonels still had a year to run. He vocally supported it, whereas his family (now in political exile) had not only actively opposed it, but sharply suffered from it. Seven years before, soon after the junta had come to power, he had returned to Corfu with the BBC and Gerald Durrell to film The Garden of the Gods, a documentary in which the son of the Greek Ambassador to London, then aged ten, ran about recreating the role of Gerald of the mid-thirties. At the same time, both his grandsons were under house arrest in Athens.

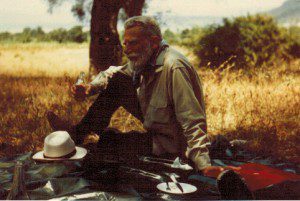

Theodore Stephanides visiting Corfu with the BBC in 1967

And yet, miraculously, the family did not allow this political difference to cause strife between them. In Island Trails itself, his only words for dictatorship, and for the extremes of fascism and communism which he considered to meet, are negative. And he had after all been bruised by the War, and Civil War, and the perspective on Greek Communism which he took from them. He ends Island Trails: ‘Twice in my life-time have all my plans been turned upsidedown by a World War. And my case could be multiplied by many millions, amounting to a stupendous total of human disappointment and frustration.’

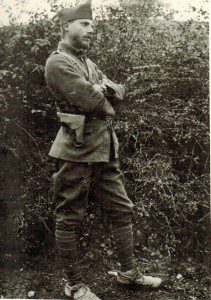

Theodore Stephanides serving in the Greek Army in Macedonia in 1917; he described this period in his memoir ‘Macedonian Medley’

And it is of course the War that is the end-stop to all the books of memoirs, since it was that that destroyed the idyllic world (for all the peasant cruelty towards animals) that they all describe. Yet they differ greatly in their mention of the War. My Family and Other Animals and The Garden of the Gods just don’t mention it; and the former mendaciously describes the family as returning to England for Gerry’s education (whereas in fact they left in June 1939 precisely because of the approaching War). Birds, Beasts and Relatives, however, ends with an elegiac Epilogue of ‘Mail’ from the various people, the last of whom is Spiro the chauffeur, who writes to Margo: ‘Dear Missy Margo, This is to tell you that war has been declared. Don’t tell a soul. Spiro.’ The more sombre memoir Prospero’s Cell contains an ‘Epilogue in Alexandria’ (Larry and Nancy left Corfu only after the outbreak of war in September) which ends with a reminiscence of April 1941 when he sailed to Crete: ‘I found myself thinking back to that green rain upon a white balcony, in the shadow of Albania; thinking of it with a regret so luxurious and so deep that it did not stir the emotions at all. Seen through the transforming lens of memory the past seemed so enchanted that even thought would be unworthy of it.’ Theodore has a similar Brideshead Revisited moment when he goes to fight in Crete in the same year. In the Epilogue to Island Trails he writes: ‘Some of the chapters of this book were roughed out while I was serving with the R.A.M.C. in the Western Desert’. He describes his 1933 touring visit to Crete with the following prolepsis: ‘Little did I guess then under what unexpected circumstances my next journey to Crete, in May 1941, was to be made. I did not see the ruins of Knossos; but I saw the ruins of Canea and the parachuted thugs who were spewed on that helpless town from the skies.’

But in general, the memoirs of all three men – Gerald Durrell, Lawrence Durrell, and Theodore Stephanides – are remarkably free of shadows, save for the friendly shadow of the olive trees. Even the description of the return of King George to Greek territory on Corfu in Birds, Beasts and Relatives contains no chill, partly because Gerry misdescribes this as coinciding with the end of the Metaxas dictatorship, whereas in fact it coincided with its beginning, and partly because the festivities are absurd, and entertainingly described. The memoirs have no plots, only episodes, which feel as though they might have been experienced in any order. The three books of the trilogy cover just the same period, from which they select incidents at will. Goodbye to Corfu these memoirs are not. Storm clouds do not gather. Whatever the reasons for the outbreak of World War II, according to these memoirs the people of Corfu, expatriate and otherwise, had nothing to do with them. I fully believe that they had relatively little to do with them. And I delight in the fact that they so obviously had so much delight in that timeless time.

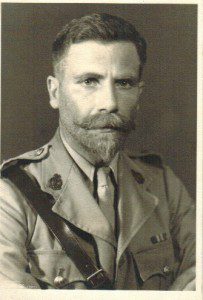

Theodore Stephanides in British Army uniform in WWII (he describes this period in his memoir ‘Climax in Crete’). All photos in this post belong to the family; anyone is welcome to reproduce them.