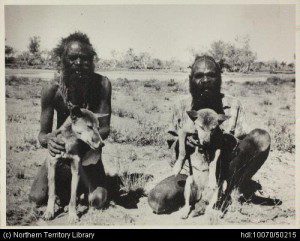

Native Australian woman nursing dingo puppies

I have recently read In Defence of Dogs (Penguin 2012, 324 pp.) by John Bradshaw, biologist and founder-director of the Anthrozoology Institute at the University of Bristol. The font is academically-small and intimidating. The book is good.

I will pass on its arguments on the assumption that they are correct. Bradshaw has done as much research as anyone – Darwin and Pavlov included – into dog behaviour, and, though some of his findings and inferences remain controversial amongst dog trainers, I have no reason to doubt them. In any case, they have prompted some interesting reflections in me about people.

Bradshaw describes the generic dog – for example, the village dog that one finds all over Africa. They all look roughly alike within the climatic region to which they have evolved as most-fit. Selective breeding – which intensified in the Western world particularly in the nineteenth century, though it had existed to some degree for ten millenia before that – necessarily produces dogs which are less-fit. The dogs no longer choose their own sexual partners, and the characteristics for which they are selected are not survival, but utility or looks. No wonder that veterinary science is now needed to bridge the fitness-gap that we have created, nor that we have created dog trainers and psychologists to deal with dogs that are suboptimal companions, given that our breeding does not select primarily for companionship. X breed, we complain, tends towards bossiness, or aggression, or anxiety, as though X breed were not entirely our own creation, and its faults the creation of our own.

I infer that we humans, by contrast, resemble village dogs. Except in aristocracies, which have their own problems with fitness, we breed more or less at will, in order to be all-round humans (give or take a degree of manual labour). Ease of long-distance travel has broadened our gene pools still further. Brave New World gives us one vision as to what would happen were it otherwise. Dogs give us another. Bred by another species, we might become subdivided into human equivalents of Miniature Schnautzers, Dobermans, Bichons Frises, Golden Retrievers, Boxers, Borzois and the rest – yet would, let us assume, retain, as dogs do, an unerring ability to identify other members of the same species whatever the differences in our appearance, and an unerring sexual preference for our own species not others. Most dogs in the Western world are now more pedigree than mongrel; even what is called a mongrel is likely to have at least one pedigree parent or grandparent. By contrast we are for the most part comfortably and healthily mongrel. We don’t need annual vaccinations and monthly worming, as our dogs do, and we are all the better off for it.

Dogs are wolves at arrested stages of development. The Pekinese skull resembles that of the wolf foetus; it just doesn’t keep growing into the long, narrow skull of the wolf. Dogs, unlike wolves, continue to play when they are adults, and are dependent on humans throughout their lives. They therefore never become psychologically mature and independent, as wolves do. Because of the consistency of food supply throughout the year, they are fertile all the year round, unlike wolves, which mate in winter in order to give birth in spring. But because the food that humans can spare for dogs is limited, they are smaller than wolves. They are less fussy about sexual partners than are wolves, which pair-bond, whereas dogs are promiscuous.

And so we are more dog than wolf. We are smaller than earliest man because of our more herbivorous diet (we are only now reapproaching the size of early humans). We are fertile all the year round, and, although we pair-bond to a degree, we are more promiscuous than wolves are. We play, with our child toys or our adult toys, at our child games or our adult games, throughout our lives. Of course, this dogginess is unsurprising, given that we created dogs in our image.

Yet the wolves from which we created dogs are not today’s wolves. Since we have persecuted wolves almost to extinction, we have negatively selected those which are most distrustful of us to be the survivors. It is likely that dogs descended from wolves living around 20,000 years ago which had a mutation which enabled them to form relationships with more than one species – our own as well as their own. This mutation served them well; their numbers now dwarf those of wolves. But, especially in the twentieth century, dog psychology has misleadingly tried to understand dogs with reference to a) modern wild wolves, which are a distrustful, persecuted minority, and b) captive wolves, which, not being able to form and dissolve their own packs, are far more agonistic and violently hierarchical than are the internally-peaceful nuclear family packs of the wild. These false reference points, combined with the false assumption (based on exaggerating the importance of genes over nurture) that dogs are essentially wolves in dogs’ clothing, has led to the stress on dominance in dog training. The assumptions are: every dog wants to be top dog; dogs treat humans as members of their pack; every attempt at dog dominance must be thwarted, and so on. In fact, dogs relate very differently to humans as compared to dogs, and tend to be far more dependent on the former, even in households of multiple dogs. At our own best, we are dog-like in our sociability with all other members of our species, not just within our nuclear families. Where we become wolf-like, in our rivalry with and violent hostility towards other packs, is at the level of the nation. Best to keep dogs within our sights.

Finally, one of the things that makes us human (and dog-like) is our ability to interact with, and nurture, multiple species. This is apparent in the story of the evolution of dogs from wolves. The explanation that wolves were initially tolerated as scavengers in villages is not sufficient by way of explanation of the beginnings of domestication – why would wolves prefer human scraps to the far better and more plentiful food that they can hunt for themselves? Nor is the idea that humans consciously took wolves to train them for various useful purposes, such as those for which working dogs are used today, entirely plausible. Wild, adult wolves would not in themselves have suggested such usages to humans. Rather, the evidence is that hunter-gatherers, past and present, adopt a variety of kinds of baby animal to bring up alongside their own young, simply for the joy of the process, a delight in their cuteness, a delight in play, and, in some cases, the status that accrues from having pets. Amongst today’s Penan of Borneo, and the Huaorani of the Amazon rainforst, parrots, toucans, wild ducks, raccoons, small deer, rodents, opossums, and monkeys are all adopted. Indigenous Australians foster dingo puppies, which, when they become unmanageable adults, are simply driven away to reproduce in the wild. It is likely that the same happened with wolf puppies – and that, eventually, a few of the puppies became domesticated as well as tame, so that they consented to reproduce in a human environment, and thus were set on their course to become dogs.

This is one of the most charming things about humans that I know – that we care about the survival of species other than our own, for reasons other than utility. We delight in nurturing, cuteness, and play, will spend our limited resources on these things, and have done so for as long as we have been human.

Native Australian men with dingoes