This article, of which an unedited version appears below, was published as ‘Our Love Affair with Anna Karenina’ here in Standpoint November 2014.

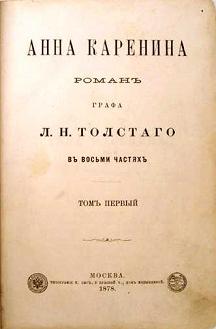

The appetite of English-speakers for Anna Karenina is, it seems, insatiable. There have been twelve translations since the American Nathan Haskell Dole’s of 1886, four in this millennium, and two in this year. In Foyles today one can choose between seven different editions, including translations from 1901 (Constance Garnett’s), 1918 (Louise and Aylmer Maude’s), 2000 (Richard Pevear and Larissa Vokokhonsky’s), 2008 (Jenny Hughes and Kyrill Zinovieff’s), and 2014 (Rosamund Bartlett’s). Selling one of the above to me, the cashier enthused: ‘it’s such a great love story, isn’t it?’ ‘No’, I thought but didn’t say, ‘I don’t think that it’s that at all’.

Yet the perception that the novel is romantic is as common as the perception that Shakespeare’s sonnets are. Let noone send a close-reading lover a Shakespeare sonnet (they are all too tricksy) – and let noone send any lover Anna Karenina at all.

Its adulterous heroine, after all, ends up as blood on the tracks – and it is by no means clear that a hypocritically-disapproving society alone is to blame for this. It has long been debated what judgment the novel makes of Anna. Some readers have found Anna to deserve her fate, others have found her not to, and some of each kind have found the novel to agree with them. Early European critics including Arnold and de Vogüé approved of what they thought was the novel’s condemnation of Anna, whereas early Russian critics such as Shestov, Strakhov, and Svyatopolk-Mirsky interpreted the novel the same way, but criticized it for this. Certain modern critics, such as Mandelker, have found the novel not to condemn Anna at all. Steiner and Bloom thought that its condemnation was contradicted by Tolstoy’s love for Anna, whilst D.H. Lawrence thought that its condemnation was subverted by the novel’s own artistry.

On this question I stand with the early Russian critics. Certainly, the Petersburg aristocracy’s toleration of ubiquitous casual affairs, and condemnation of Anna for the relative urgency and honesty of her own, are presented as loathsome. But the novel nonetheless suggests that Anna would have done better by herself, man, and God, had she resisted having the affair; or, failing that, had conducted it in the manner of a Betsy Tverskaya – discreetly, fleetingly, and with minimum disruption to her family. Thomas Mann was right to find ‘a certain contradiction inherent in the author’s originally moral theme, in the charge he raises against society; for one wonders what weapon of punishment God might use if society behaved other than it does’. And the punishment is extreme, anticipating as it does Pozdnyshev’s murder of his wife for adultery in The Kreutzer Sonata, on which Tolstoy had started work before completing Anna Karenina.

The novel’s famous epigraph has focused this debate. ‘Мне отмщение, и аз воздам’ is the standard Slavonic translation of a divine prophecy quoted by Paul to the Romans. The passage from the King James Authorized translation (with the relevant words italicized) is:

Dearly beloved, avenge not yourselves, but rather give place unto wrath: for it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord. Therefore if thine enemy hunger, feed him […] Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.

(Romans 12.19-21)

The second and third sentences quoted make clear that Paul is quoting in the spirit of the section of Leviticus in which God tells Moses:

Thou shalt not avenge, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself: I am the Lord.

(Leviticus 19.18)

But Paul is not in fact quoting this passage, but slightly misquoting from Moses in Deuteronomy:

To me belongeth vengeance, and recompence; their foot shall slide in due time: for the day of their calamity is at hand, and the things that shall come upon them make haste. For the Lord shall judge his people.

(Deuteronomy 32. 35-36)

To leave vengeance to the Lord is, however, merely to defer and outsource it. Can the epigraph be suggesting to its readers that they should not judge Anna, but leave it to the plot, which lies in the author’s godlike hands? Anna can be seen as the author of her own downfall, by degenerating into febrile narcissism and delusion. But this degeneration seems underdetermined by her character as initially presented (by an idealising masculine narrator), facing such opprobrium as it encounters. Anna’s degeneration too, then, seems somewhat imposed by the author, and part of her punishment. It is as though the progression which Anna’s character had made through the novel’s successive drafts from a crude coquette to the Anna we know, is partially reversed. In making Anna as attractive as she initially is, Tolstoy may have been testing how loveable he could make an adulteress, and still show the wages of sin.

The novel’s subtitle ‘роман’ (‘roman’) is a euphemism for an affair, so connected were the concepts of the European novel, and adultery – and of adultery, and a finite piece of entertainment. The novel’s title and subtitle therefore hang above it rather as Pilate’s judgment hangs above Christ on his cross, stating the crime of the man he has condemned to death (having a ‘roman’) in a manner indeterminately ironic, honouring, and accusatory. Within the novel Tolstoy, Pilate-like, both condemns Anna’s society for condemning her, and imposes the death penalty (which that society did not possess) for the sake of a higher cause than that society can comprehend.

Today, only a few non-Western polities impose the death penalty for adultery, and our own society imposes so few penalties of any kind for it that the term, like ‘fornication’, is beginning to sound old-fashioned. Today, Anna’s friends would remain such. She could occupy a box at the Royal Opera House without incurring scandal or insult. Karenin would be obliged both to divorce her, and to give her custody of or access to their son. His career and social standing would be largely unaffected. In the novel Oblonsky, in his easy attitude towards his sister’s adultery, represents the liberal future in which women are ever less likely to commit suicide if they behave as she does. D.H. Lawrence and his professor’s wife, Frieda Weekley, read Anna Karenina during their elopement in a ‘how to be happy though levanted’ spirit. Fewer than four decades after the novel’s writing, they became happy. A similar couple today would need neither to elope, nor to turn to the novel to work out how to avoid its kind of tragedy.

But the novel contains another story. Levin was introduced in the novel’s third draft, and his story was expanded over the remaining two drafts until it occupied slightly more than half the novel. A Boston Literary World review of 1886 noted that the novel oscillates from side to side ‘like an express train’ on a winding route – and so it does. We are moved from Anna’s Petersburg to Levin’s estate, and back, with occasional mediation via Moscow and its consummate social mediator, Oblonsky. But the novel does not oscillate to its end. In its serialized version, the words describing Anna’s death were followed by a note indicating that the novel was to be continued. Clearly, it was not Anna’s life that was to be continued.

There ensued an impasse. Tolstoy’s editor did not want to publish Tolstoy’s eighth and final part. He not only disapproved of its hostility to Slavophilism (Vronsky’s volunteering in Serbia has recently been echoed by Russian volunteers in the Eastern Ukraine), but thought that its concern with Levin to the exclusion of Anna was extraneous to the novel as a whole. Tolstoy therefore published the section privately, fifteen months later. The long pause had permitted resonance to Anna’s tragedy. Or alternatively, as in life, and as in Levin’s life, other concerns had superseded it. Levin represents that which goes on – at least, for a further nineteen chapters.

Yet most interpretations of the novel have overlooked Levin. Certain early translations, such as the French one consulted by Dole in 1886, reduced Levin’s story. The film adaptations of 1935, 1947 and 1967 all end with Anna’s suicide, as though returning the novel to its early state, in which Levin did not exist. Joe Wright’s 2012 version is exceptional in giving Levin’s story weight.

To be fair, Tolstoy named his novel for Anna, having dismissed the early working title of Два Брака (Two Marriages). When he wanted to emphasise contrasting principles in his titles, he did so: War and Peace, Master and Man. Nor did he trouble himself to create obvious connections between the stories. After Vronsky’s pursuit of Anna frees Kitty to marry Levin, the couples have no significant effect on each other. Levin and Vronsky meet thrice, Anna and Levin meet for a few hours, and Anna and Kitty meet for a few minutes.

Nonetheless, many critics of the last few decades have argued that the two stories are connected, following Tolstoy’s own claim that the novel was ‘законченный’ (well-finished). Such critics point out the similarities of Anna and Levin as great readers, strongly invested in their relationships, who are capable of extreme mental states and suicidal thoughts. The fact that they end up filled by misanthropy and philanthropy respectively is indicative of how the managed contrasts between them work in Levin’s favour. Anna elopes as Levin marries; Anna honeymoons in Italy whilst Levin honeymoons on the land; they meet in Moscow, where Levin becomes a father and Anna commits suicide.

Yet the stories’ suggested contrasts fail to adequately encompass either. For one thing, Levin and Anna are at very different stages in their marriages. A fair comparison of Anna is not to the newly-wed Levin or Kitty, but to how they might be nine years later. A different justice operates in the two stories: Levin has had pre-marital affairs as Vronsky has, but comes away relatively unscathed by the novel’s plot and its implied judgment.

More importantly, Levin’s and Anna’s concerns are simply too divergent to allow their stories to shed much light on each other. At the end of the novel, Levin, happily married, is concerned with why to live under any circumstances given that he will one day die. Anna, unhappily married, had been concerned with how to live under her particular circumstances, which had obscured from view the largest questions such as occasioned Tolstoy’s own breakdown on finishing the novel. Alexandr Zarkhi, in his 1967 film version, interpolates into their one meeting a discussion about suicide – but even on this subject they, like their stories, have relatively little to say to each other.

The novel’s very composition as separate stories (Levin’s was spliced into Anna’s) permits a difference of genre, rather as people’s actual lives can seem to belong to different genres. Whereas Anna’s roman aspires towards the condition of the European novel (Madame Bovary precedes it by two decades), Levin’s story has the aspect of autobiography. Tolstoy’s diary has a gap during the composition of the novel, as though writing Levin’s story had replaced its function. In comparison to Anna’s omen-fulfilling tragedy, Levin’s muddling through to his final epiphany feels realistic.

But if Levin’s concerns are of limited relevance to Anna, of how much relevance are they to us? Most of us have no option of choosing life on a country estate over urban life, and the town-country divide carries a fraction of the moral weight which it did in Tolstoy’s time and country. Unlike Levin, who sees in the peasant Platon an incarnation of the Russian virtues, we no more seek for wisdom or virtue in one class than in any other. Levin anticipates easy marital bliss, as none of us do now. We do not need Levin’s experience of post-marital readjustment to advise us that no cohabitation is stress-free. Certainly, the revulsion which some of us feel at Americanization (its materialism, triviality, and contempt for individual and cultural age) echoes Levin’s and the novel’s dislike of Westernisation as represented by America’s nineteenth-century counterpart. The novel’s references to English fashions, goods, sports, and names (such as Betsy) are nearly all connected to morally-suspect, Westernising modernity.

But where Levin is likely to retain the strongest interest is in his construction of his own problems. Anna seems to herself and us to be passive to her problems. She falls for Vronsky despite herself; she leaves Karenin because she feels that she can do no other; she declines helplessly into neuroticism. Levin, by contrast, struggles with how to live because of the enormous historical, moral and metaphysical significance with which he invests his life-choices. In this he is the opposite of Oblonsky, who denies significance to any of his decisions. And in this is likeable. If he ties himself in mental knots of his own making, there is something sympathetic and admirable as well as ludicrous in him doing so. He keeps changing his mind – wanting to improve his estate, marry Kitty, marry a peasant, marry Kitty again, wanting to die, wanting to live – but only because he embraces each position so firmly that he is temporarily blind to its limitations, and thereby reveals these limitations to us.

His lurch at the novel’s end into a perception of the meaninglessness of a finite life will be familiar to many people living in a society from which God has retreated further than from 1870s Russia. Those of us who have known it get around it in our different ways. Levin’s intellect almost prevents his attainment of faith, and his eventual compromise with it – that Orthodoxy is that form of truth which God has made accessible to him, as a Russian – is familiar to many people of faith today. Many of us have known religious joy, and have known its passing. Tolstoy kindly drops the curtain on his novel before Levin’s can pass. F.R. Leavis rightly found ‘that the breakdown of Tolstoy into the old Leo is here portended’. Tolstoy decisively rejected Orthodoxy, although not Christianity, after finishing Anna Karenina.

In Russia, the novel which was in its own time judged to be conservative, and was only tolerated in the Soviet literary canon on sufferance as realistic, now has little appeal. Modern Russian society resembles Tsarist society still less than does modern Britain, in that its class structure has been smashed, and divorce rates are higher still than those here. If there is one thing that still appeals, it is Levin’s quest for how to live. It is as though the whole Soviet period represented Levin’s young adulthood, in which he turned atheist and ridiculed the Church. In the tough post-Soviet years, when secular society promoted nothing but Westernisation and wealth-accumulation, many people returned to Orthodoxy, and its implicit patriotism. One does not know how long this will last. Levin’s perception was that the Russian people, and its perception of truth, would endure; and the post-Soviet revival of Orthodoxy might be evidence of that. But, as we feel at the ending of that passionate, anti-romantic, conflicted novel that is Anna Karenina – it is too early to tell.