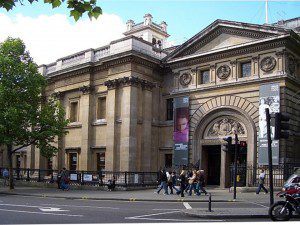

National Portrait Gallery, London, 17th March-26th June 2016

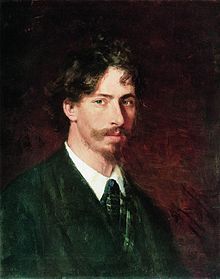

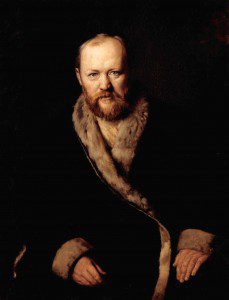

Ilya Repin (1844-1930), Self-portrait, 1878

One of the good things about this very good exhibition is that it is happening at all. Despite the current level of tension between the UK and Russian governments, 2016 has been declared the UK-Russia Year of Language and Literature. As Mikhail Shvydkoi, the Russian President’s Special Representative for International Cultural Cooperation, has said: ‘In the context of the current political and military crisis, a year of language and literature seems to be very important. It proves that culture and nations have a presumption of innocence.’

Admittedly, if the 2014 UK-Russia Year of Culture is anything to go by, this Year will have a very high profile in Russia and a low one in the UK (none of my highly-cultured English acquaintances were remotely aware of the last Year taking place – which is perhaps unsurprising, since UK television didn’t touch it, whereas Russian television followed the Year’s events in Russia closely). The 2016 Year was launched at the Royal Festival Hall on February 25th with a live Philharmonia Orchestra concert screening of the 1927 Greta Garbo film Love, based on Anna Karenina. I had no idea. Had you, highly-cultured UK-based Reader? Has this year in part been launched to make up for the shortcomings of the last one?

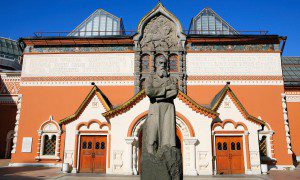

Nonetheless – I welcome its occurrence. And there is a felicitous coincidence in the fact of two of the participating institutions, the National Portrait Gallery and Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, celebrating their hundred-and-sixtieth anniversaries this year (one speculates – how many such parallel celebrations have taken place over that century and a half?) So, whilst the Tretyakov is hosting an exhibition of highlights called Elizabeth to Victoria: British Portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, the National Portrait Gallery is hosting ‘Russia and the Arts’, a more focused selection of portraits of cultural figures and patrons between 1878 and 1914, ranging from realism to impressionism and symbolism.

Contemporaries at opposite ends of Europe: The Tretyakov Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery

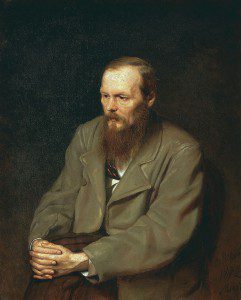

The question that the exhibition raises but does not answer is why the great Russian artists of this period are not better known in the West. This cultural gap is even mimicked by their absence as subjects in the exhibition. Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Chekhov, Tchaikovsky, and Mussorgsky, are all present in the portraits, in the exhibition’s (somewhat obtrusive) accompanying music, and in the Western mind; but the show’s active stars – Repin, Perov, Braz, and Serov – are undepicted and hardly known. Perhaps their portraits were not thought worth bringing precisely because nobody had heard of them. Admittedly, twelve years ago the National Gallery’s hit exhibition ‘Russian Landscape in the Age of Tolstoy’ brought some of their names into the English consciousness, but since then they have faded again. Rembrandt and Goya (to name just two subjects of specialist exhibitions at the National Gallery over the last two years) can sell out exhibitions with merely a lesser-known part of their oeuvre – whilst all Russians prior to the avant-garde are required, kommunalka-style, to share an exhibition between them. It is not even as though their idiom is foreign to Western aesthetics; Western trends had by this point been thoroughly assimilated in Russia (to see the status quo ante, see the early sections of the Tretyakov Gallery, and the style of the building itself).

I can only suggest that Russian paintings of this period tended to stay in Russian private houses, or in collections such as Pavel Tretyakov’s, and that Russia was wretchedly onerous to travel to (with passports obligatory, distances big, and railway hotels dire).

But this exhibition’s paintings would have been worth a pilgrimage then, and are certainly worth a trip to London now. For most of them have been in the presence of not just one, but two, great artists, and are the result of their conjunction. Their overwhelming concentration is on faces, and especially eyes, whilst the clothes, background, and hands play supporting roles. None of them are weak, but for me a few stood out. Most of all, Vasily Perov’s Dostoevsky.

By 1872 Dostoevsky had already written ‘Notes from Underground’, Crime and Punishment, and The Idiot. He looks down to his right, and sees terrible things – they return to the viewer’s mind from his writings when looking at him – but watching him see these things feels like a violation. Although I was strongly drawn to it, I also felt forbidden to look. He better than anyone could describe such an experience (see the repeated descriptions of Ragozhin’s devastating portrait of Christ in The Idiot). And yet he also comes across as a man that one could trust. And the painting is so famous in Russia that it has been domesticated onto stamps and biscuit tins.

Perov’s Ostrovsky (the hugely popular playwright), of the preceding year, is also remarkable.

Then there is Repin’s Mussorgsky, painted in hospital shortly before the latter’s death from alchoholism in 1881 at the age of 42, which draws only a small part of its great power from that fact.

By contrast Chekhov, himself only six years from death, gives Iosif Braz an utterly cold stare through his pince-nez. Some reviewers have commented that this portrait reveals his identity as a doctor. To me, it reveals a side of Chekhov that the English are reluctant to acknowledge: his severity, his detachment, and his ability to look at, and not to look away from, the most terrible human circumstances (he inspected prostitutes for venereal disease; he chose to visit the Sakhalin prison colony).

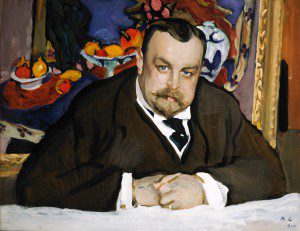

Stepping beyond realism in the new century is Valentin Serov’s Ivan Morozov, with the latter’s possession, Matisse’s Fruit and Bronze, behind him. Standing in front of this painting, one experiences infinite aesthetic feedback, as the two paintings of 1910 bounce off each other.

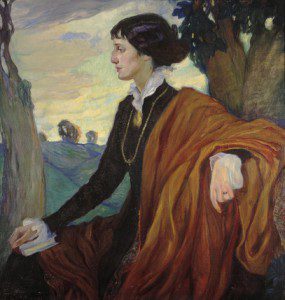

Finally, there is Olga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia’s (a pupil of Repin’s) twenty-five year-old Anna Akhmatova in 1914. This painting goes down well with English viewers because it reminds us of Virginia Woolf, in some ways a counterpart figure. And if there is one role that a country-hyphen-country Year can play, it is the demonstration of similarity.