Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art

3rd October 2013 – 5th January 2014

British Museum

I have only twice felt sick in an exhibition. The first time was in the reliquary of the king’s Residenz in Munich. I’d wondered in in a spare hour in a Protestant-touristic spirit, and found myself in a dark room filled with tibulae, fibulae, metacarpals and crania, pearl-white, pearl-encrusted, silver-set, velvet-cushioned former frets of the bodies of the greatest spirits to have had bodies.

I looked at the first few in wonder: the thigh bone of Saint John, the wrist bone of Saint Jude. Then my eyes scanned the room and guaged quite how many thighs, wrists, skulls, and kneecaps I was within venerating distance of – and my stomach gave a lurch. I yet again endorsed my decision (taken after an anguished dilemma at the age of fifteen) not to become a vet, or anything else of a surgical nature. But I stayed. Ever the professional tourist, I felt the duty of thoroughness to all the relics I had not yet seen. And as I looked at the other bones of the Wittelsbach collection, I found my stomach settling again. Through accustomisation, I was able to see them all.

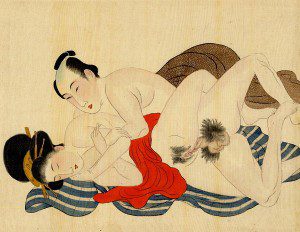

The second occasion was a few weeks ago at the Shunga Exhibition in the British Museum. I looked at the introductory love scenes in the same spirit that one reads the opening chapters of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. ‘But where’s the gamekeeper?’, one asks oneself. ‘And this was banned?’ But as in certain real life sex scenes, one goes in cold, and should be gradually warmed up. The foreplay in this case was brief. Come the third painting, and WHAM. A twenty-centimetre vagina gaping ten centimetres open. A penis standing jauntily nearby. A reclining Japanese woman and man attached to these objects, smiling in different directions. Next: a twenty-two centimetre vagina gaping eight centimetres wide, red and folded as a pomegranite, black hairs waving scrupulously away over white skin. Veins on the penis bulging like erect penises under trousers. Smiles. On to the third… Then, as in the reliquary, I made the mistake of looking up. The room in which the exhibition was held is long, and one penetrates it much further than one at first thinks possible. My mind made an involuntary calculation, and realised that it had some two hundred vaginas, two hundred penises, and forty thousand neatly choreographed pubic hairs yet to assimilate. My stomach gave a lurch. Perhaps this is what an orgy feels like, if one wonders around uninvolved.

It didn’t help that this was a Members’ late night opening, and it felt somehow transgressive being in the Museum in the first place – flitting about amongst the ancient objects like an escapee tourist from the wrong century, which one always in fact is. There were no windows in the exhibition, but its darkness was deepened by knowledge of the night sky outside, giving it something of the feeling of a bar. I leaned on the rail to gape at my tenth couple. A man came and leaned next to me. Looking at the same painting in an exhibition can be a great way to start a conversation with a stranger. One has something in common, and perceptions to exchange. But not in this exhibition, not with these paintings, not in England. There was absolutely nothing that either of us could say.

But for all that there was plenty to be said, and for the fact that I found it I was grateful again to nausea-quelling habituation. The exhibition was curated with maturity and accessible intellectual zest, and I learned a fair bit about the culture which many Westerners find the most foreign amongst its neighbours, during centuries for most of which it was closed against Western attempts to reduce its foreignness. Shunga, I learned, means ‘spring pictures’. They were produced for and owned by all classes. They served in part as an instruction manual, for example for newly-weds. This would account for their stylised clarity; one can imagine them being held up at the front of Dutch sex education classes today, no enlargement necessary. It has sub-genres, one of which is the political-satiric, and it was this one that presented a slender bridge to European art of the same period. A few of Thomas Rowlandson’s prints represented the late seventeenth and eighteenth century tradition (driven decisively underground by the Victorians) of satire through representation of sex. This is distinguishable, however, from satire of sex. In the shunga I often felt that sex itself was part of the joke, involving the kind of grin that one finds also on the face of Pan and the satyrs.

A variety of kinds of sex, as well as genres of representation, were on offer. There was one picture of an older and younger male lover lying happily under a blanket which was being rearranged by a female attendant. There was another – placed at the very cervical end of the exhibition – which was apparently of two young male lovers but turned out, on closer inspection of their uniforms, skin pigmentation, and accompanying inscription, to be a Japanese soldier raping a Russian as a metaphor for victory in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5. This was an exception. The sex represented in nearly all the other pictures was comfortably egalitarian; though all were created by men, both the women and men were enjoying the event. It was leisurely. These pre-orgasmic people seem to have all the time in the world. They have conversations, as in the early 1820s painting by Katsushika Hokusai (of The Great Wave fame), in which a man sucks the breast of his pregnant wife, whilst their conversation is rendered in a casual grass script all around them.

The leisure of pleasure is something which belongs also to the Floating World – the world of geishas and courtesans with which shunga has kinship (although the couples the latter depicts are spouses and lovers, not professionals and customers). The delights of this world were evoked by Asai Ryoi in the mid-1660s as follows:

Living from moment to moment; singing songs

and drinking sake whilst gazing at the moon,

the snow, the cherry blossoms and the maple

leaves; merrily drifting along…your spirits

unsinkable as a gourd riding a stream:

that is life in the floating world.

Another poem of a similar genre, but unknown date and author, announces magnificently:

Onto his silent lap

she lowers

her eloquent hips

This epitomises the stillness, as well as the eloquence, of shunga. The faces are often smiling, and are nearly always close to each other. Rarely is sex from behind; we are thousands of geographic and cultural miles, as well as two millennia, from ancient Greek vases and their repeated satyric penetrations from the rear.

And yet…and yet…I never saw what I feel by ecstasy. I saw delight, tenderness, love, and great contentment. But not the smelting love-lust of Giulio Romano’s Lovers (c. 1525) as they look into each others’ eyes at a few centimetres’ distance. Rarely do shunga couples look into each others’ eyes. Nor do they have the trancendent delight and creative fun of the couples in erotic Hindu temple sculptures. Finally, to my taste the genitals were too stylised. It came as a relief, part way through the exhibition, to find a few sixteenth century Chinese erotic paintings included in order to suggest their influence on early shunga. In these everything apart from the women’s feet was more realistically sized, and more decorous. I was reminded of the Masterpieces of Chinese Painting 700-1900 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum which, although necessarily selective (representing twelve centuries of a vast empire’s art in three small rooms) nonetheless interestingly contained no sex or violence.

No sex…one muses…the Chinese got to be over a billion people somehow. But to have sex is not to represent it, as the Victorian population explosion makes abundantly clear. Representing sex is a choice which certain cultures have at certain times made, and at other times (such as Japan at precisely the time that Toulouse-Lautrec and Picasso were becoming inspired by shunga) shunned. There are certain things, like the insides of vulvas, and bones, which we often prefer to hide. And when we then find ourselves confronting them, we find the need to assume a position: of anatomist, worshipper, lover, or art critic.