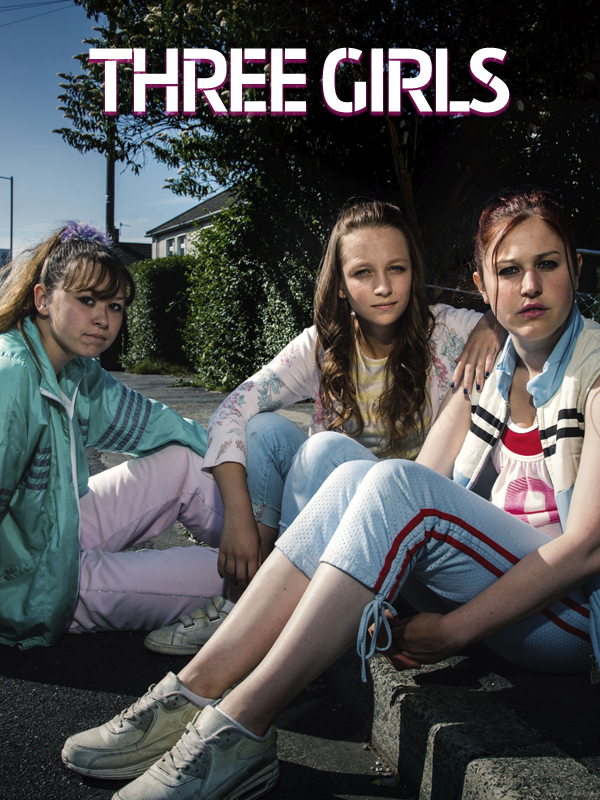

BBC 1 miniseries, 3 episodes of 60 minutes

Screenwriter: Nicole Taylor

Director: Philippa Lowthorpe

Broadcast 16-18 May 2017

I am in awe at BBC drama. In the past week I have watched both BBC2’s adaptation of Mike Bartlett’s 2014 play King Charles III, and BBC1’s miseries about the Rochdale child abuse scandal, Three Girls, and have been bowled over by both. But the latter moved me most.

Its muted title foregrounds the fact that writer Nicole Taylor had to select a manageable number of protagonists from the forty-seven girls who were interviewed for the Rochdale trial. But the number forty-seven is misleading in its precision. The drama stresses the fact that interviewing relies on willing interviewees, and that such willingness was often lost due to police contempt towards the abused, and to the abusers’ successful emotional seduction and/or terrorisation of their victims. The actual number of girls who were abused by the nine men convicted in Rochdale in 2012 will never be known. Nor will the real number of men involved in their abuse. In the similar case that took place in Rotherham, it has been estimated that one thousand four hundred children were involved over a sixteen-year period. The title’s lack of the definite article suggests an element of randomness in the dramatist’s scoop out of the vast vat of misery that is her subject.

The impersonality of the girls’ eponymous enumeration recalls the ‘Girl 1’, ‘Girl 2’ format by which they were known when they came to trial, and by which they are forever to be known in relation to this case. The term ‘girls’ is, therefore, sure-footed. These were not girls in the sense in which women are patronisingly, affectionately or sexually termed such, but were legally and literally girls. The title points straight at them, as does the series itself, rather than at their abusers. Finally, the title has an echo of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. Of the originals of the three protagonists (renamed Amber, Ruby, and Holly, played by Ria Zmitrowicz, Liv Hill, and Molly Windsor), only two were sisters. To the extent that they moved in different patterns over time towards and away from cooperation with the police, and to the extent that ‘Amber’ bullied the others into cooperation with their abusers, they did not operate harmoniously. But, in the end, all three pulled in the same direction – and, it seems, have managed to continue with life. Certainly, they were willing and able to act as consultants to this series: Molly Windsor, who plays Holly, described her real-life counterpart as ‘incredibly strong. I don’t think [the abuse] will ever leave any of them, but she is brave enough to go through it again with us to film it.’

I watched its three episodes back-to-back on iPlayer. Early on in the first, I made myself a whisky and coke. By the end of the third, I had finished three. This might seem to be in bad taste, given that the girls in the Rochdale scandal were all given litre bottles of vodka as part of their grooming, and that the sex then demanded was presented as repayment of gifts received. But it felt like the right thing to do – to open myself completely and emotionally to this drama, in sympathy with these girls, whilst – on a parallel track of my mind – reliving my early teen years, and thinking how different they were from those of these girls. And yet, as Molly Windsor remarked of the girls with whom she spoke: ‘Those girls did nothing I’ve not done. You go out with friends at night when you are younger and get in a taxi, and you don’t expect anything to happen – but what happened to them was appalling.’ There, then, but for the grace of God, went the actor. And there, but for the grace of God, went I.

I was aware of the Rochdale abuse story before the trial of 2012. In 2011 Andrew Norfolk of The Times had broken the story of a pattern of child sex abuse in the Manchester-Rotherham area to the national press, along with a critical account of failures of the police to investigate it properly. This drama stresses these failures, especially on the part of the CPS (who seem to have been blinded by snobbery towards these disadvantaged, sometimes difficult, girls) – and also of local social services (who seem to have focused on the welfare of the babies born of these rapes to the total exclusion of their mothers, as though the remit of their care extended only to children younger than ten). In doing so, it bookends the trial with the narrative of its delay: the 2011 news story helped propel the case to court in the first place, whilst this story vindicates the first one, and leaves the troubling sense that not enough has yet been done.

A surtitle near the end of the third episode informs us that the one person who apparently did the most to try to bring the abusers to justice (sexual health worker Sarah Rowbotham, herself a consultant to the drama in which she is played by Maxine Peake), was made redundant shortly after the trial. In the wake of the success of the drama, there is now a campaign to have her honoured – and one may hope that the minds of police and social services country-wide have again been concentrated on this issue. Detective Constable Maggie Oliver, played by Lesley Sharp, resigned from the police in October 2012 over their handling of the case, and told The Guardian ‘I’m speaking to kids who are telling me that even to this day they are seeing offenders that they’ve named, walking around Rochdale. Somebody saw one in London, another person told me that one has moved around the corner from her.’

The very fact that the drama was made, though, is encouraging. We, the license-fee-payers, have collectively helped to fund this piece of national soul-searching. Fine British Asian actors such as Simon Nagra and Wasim Zakir bravely took on the role of Muslim villains, and the drama, though it does not concentrate on them, does given an insight into the defendants’ attitudes towards the end. ‘Daddy’ (Shabir Ahmed, played by Nagra) launched into a speech at his trial (of which the transcripts form the basis of the screenplay at this point), to the effect that these white girls had already been tainted by sex and alcohol when they found them; they were prostitutes trying to reclaim their honour after the event. Soon after the trial scene, we see a community meeting in which Rochdale Muslims air contradictory recriminations – against whites for no longer taking their cabs (several of the abusers were drivers), and against the misogyny which existed amongst some of their own men. In relation to the similar Oxford case, Dr Taj Hargey, imam of the Oxford Islamic Congregation, said that the views of some Islamic preachers towards white women were appalling, encouraging their congregations to see these women as decadent and deserving of degrading punishment. Julie Siddiqi, executive director of the Islamic Society of Britain, has called for an increase in the number of women at the top of Muslim organisations, arguing that their domination by men may have contributed to their community’s silence on grooming. Certainly, given that in all these British Pakistani sex scandals the men have been acting in concert, and given that minority communities tend to be particularly tight-knit, it seems unlikely that of all the people connected to these married, Mosque-attending men, nobody knew anything about what was going on, or had any suspicions about it.

Simon Nagra as ‘Daddy’ in the dock at his trial

One reason why the drama is brave is the same reason for which Andrew Norfolk initially shied away from writing about the Rotherham case: that ‘I didn’t know how to tell it without saliva dribbling down [BNP leader] Nick Griffin’s chin.’ But it handles such a response well, dramatising it in angry white men outside the court-house shouting and chanting. They are a wholly negative element. The police officer accompanying the girls into court tells them to ignore them, which they do; similarly, the drama by and large places racist reactions to the events as all but beneath its notice.

The girl actors too were brave, and they were exceptional. The most praise has been directed at Molly Windsor’s Holly, but – I feel – for the same reasons that the abusers were the most attracted to her: she is the prettiest, most thoughtful, intelligent, and dignified of the three. But one is also aware of her performance as a performance. It is palpably a piece of great acting. One tends to overlook Ria Zmitrowicz’s wounded, bullying Amber and Liv Hill’s easy-going, mentally-restricted Ruby, as simply the real thing. Such ‘performances’ must not be ignored. And I was glad to see that the camera averted its eye during the drama’s sole rape scene; there is no salacious interest in the girls or the actresses who play them.

The drama brought home to me several points about the case that were new to me, or about which I had not begun to think.

These girls had boy peers – spotty teenagers, who would also queue up at the sexual health clinic for their free dose of condoms. They faded very quickly from the drama, and, it would seem, from the girls’ lives, as they were eclipsed by men with kebabs and vodka and cars. These cabs assume huge metaphoric importance, as they taxi the girls – vodka bottle in hand – to the hell that they are capable of creating.

Our justice system makes it hard to bring such abusers to book. In the case of internet-based crime, such as downloading child pornography, or engaging in paedophile chat, justice is swift and strong. But in the case of actual child rape of this kind, it is much harder to bring a conviction, even though the crimes are far more severe: they are the events of which other men are imprisoned for viewing images. The police response has apparently been: children whose abuse exists in photographs are innocent victims. Children whose abuse exists in actuality have made poor lifestyle choices and would make unreliable witnesses whom no jury would believe. Our justice system also requires such girls, if they do come to court, to answer hostile cross-examination by as many defence barristers as they had rapists who plead innocent. The Rochdale girls’ stamina and courage in the face of this ordeal is one of the most striking features of the film.

Molly Windsor as Holly testifying from an adjoining room by video link during the trial of her abusers

When women get involved in such a case, things improve. The two adults who did most to bring the Rochdale case to trial, and who resigned or lost their jobs over it, were women – as were the writer and director of this drama.

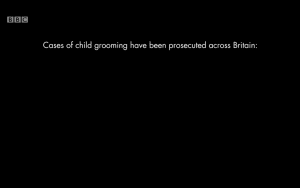

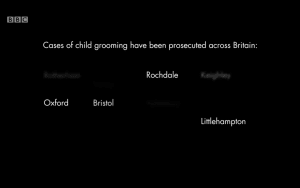

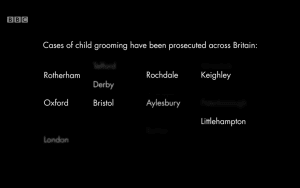

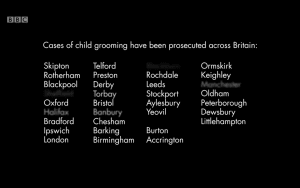

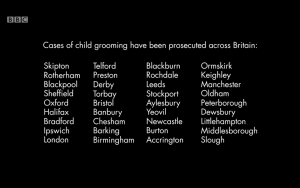

These things went on in many more places than Rochdale. There is a devastating final graphic, in which the words ‘Cases of child grooming have been prosecuted across Britain’ appear in white at the top of a black screen. The word Rochdale then appears at a random place beneath. Then Oxford. Then Littlehampton. Then Bristol. Within a few seconds, the whole screen is filled with British place names.

I have mentioned the Oxford case so many times because it is the one that I feel closest to. Between at least 2004 and 2012 at least three-hundred and seventy-three children, some as young as eleven, were targeted for sex by gangs of men in Oxfordshire. Seven men were brought to trial in May 2013. I moved to Oxford in 2008 and left in 2012; news of the scandal was coming out before I left.

This was far worse one than the Rochdale case, and the only reason I can suggest why Rochdale and not Oxford was selected for the drama’s subject was that the latter was too distressing for national television. In Rochdale the men seem to have been opportunistic. They obtained easy sex once they had established their method, but they were not before these events systematic paedophiles, criminals, or pimps. Oxford’s ringleaders were established criminals who created a prostitution business that trafficked local girls to as far afield as Bradford, London and Bournemouth, in order to sell them for sex for up to £600. The girls were not only given vodka, but heroin and crack cocaine. Worst of all, the sex often involved severe degradation and torture. One twelve-year-old was left covered with burns from where cigarettes had been extinguished on her body.

In 2008 I was working at St. Hilda’s College and living nearby, just behind the University running track where Roger Bannister ran his four-minute mile. Opposite the track, on the other side of Iffley Road at number 137, stood the Nanford Guest House. I passed it every day on my cycle to work. Like much else on Iffley Road, it didn’t look particularly salubrious, but I thought nothing else of it until the details of the paedophile ring began to emerge. One guest had heard screams in a neighbouring room and had called the police, who had arrived to find a naked fourteen-year-old cowering in a cupboard covered in urine. The guesthouse was regularly used – along with local graveyards – for group sex. I looked at online reviews of the Nanford Guest House. Here is one from 2006:

‘The rooms are comparable to a 1 star guest house in Bombay, actually no they are worse….Hair in the sink, dead flies, ants, a strong odour of what I could only hope was damp., mould, stains which I can only guess was tea- on the walls, floor, ceiling. DISGUSTING!!! After we decided staying would probably result leaving with a possibly fatal disease…we asked to leave. The owner was somewhat unsuprised when we told him the room was cold and unclean and out rightly refused us a refund and actually told us to [–]!’ We left in shock without our money and no where to stay. He’s a very rude, objectionable person.’

And, it seems highly likely, either complicit or culpably passive at the sight of groups of grown men regularly entering and re-entering the premises without luggage and with young girls who were obviously not their daughters. The owner, Jeremiah Cronin, and his two sons with whom he managed the guesthouse, were arrested only after the abusers were sentenced (apparently their earlier arrest would hinder the main investigation; one wonders why), but released without charge in September 2013.

Police waiting to arrest Jeremiah, John and Bart Cronin at the Nanford Guest House, Iffley Road, Oxford

One reviewer of the guesthouse – which has now been closed – said that his stay there had left a nasty taste in his mouth in connection with Oxford. The same is true for me, of this scandal and Oxford. I had never liked either the Iffley or the (neighbouring) Cowley Roads. I had never shared the romanticism that the Cowley Road’s supposed rough-and-ready charm evoked – an earthy antidote to the rarefied Varsity centre – with its kebab shops where, it turns out, children were being intoxicated and abused out back. For the same reason, I have only qualified sympathy for the Save Soho Campaign. If the losing of independent shops and excellent theatres is the price of releasing the sex slaves of Soho from their chains, then I would rather the region be turned into a giant CrossRail station and a Sainsbury’s.

Balti House in Rochdale, one of the kebab shops used by child abusers

But when we turn our thoughts to those girls and women, we find ourselves confronted by another category of person: the Hollies, Rubies and Ambers of Latvia, Ukraine and Sudan. On their behalf the BNP might not show so much outrage, illegal immigrants as they are. And so I must mention the greatest film on the subject of sex-trafficking, greater even than this drama – Lukas Moodyson’s 2002 Lilya 4-Ever. An overwhelming, transcendental film about a sixteen-year old Russian Estonian trafficked to Malmö, I saw it on its British release at a cinema in Soho, and came out doing something I had not done before and have not done since – crying with anger. Anger that Lilyas existed in the streets all around me, and that their rescue was no kind of priority. A lower priority than saving independent shops, for some.

I am glad to say that art helped. The film was promoted by Amnesty International and shown to police forces in Sweden, Britain and Russia, with resultant changes in the law and renewed efforts at its enforcement. I wish the same fate for Three Girls – that it is art that makes things happen. Who knows? Perhaps even in its effect on the Rochdale men who at the time of their trial seem to have been unrepentant – and who may, in their prison cells, have access to a TV to watch it.