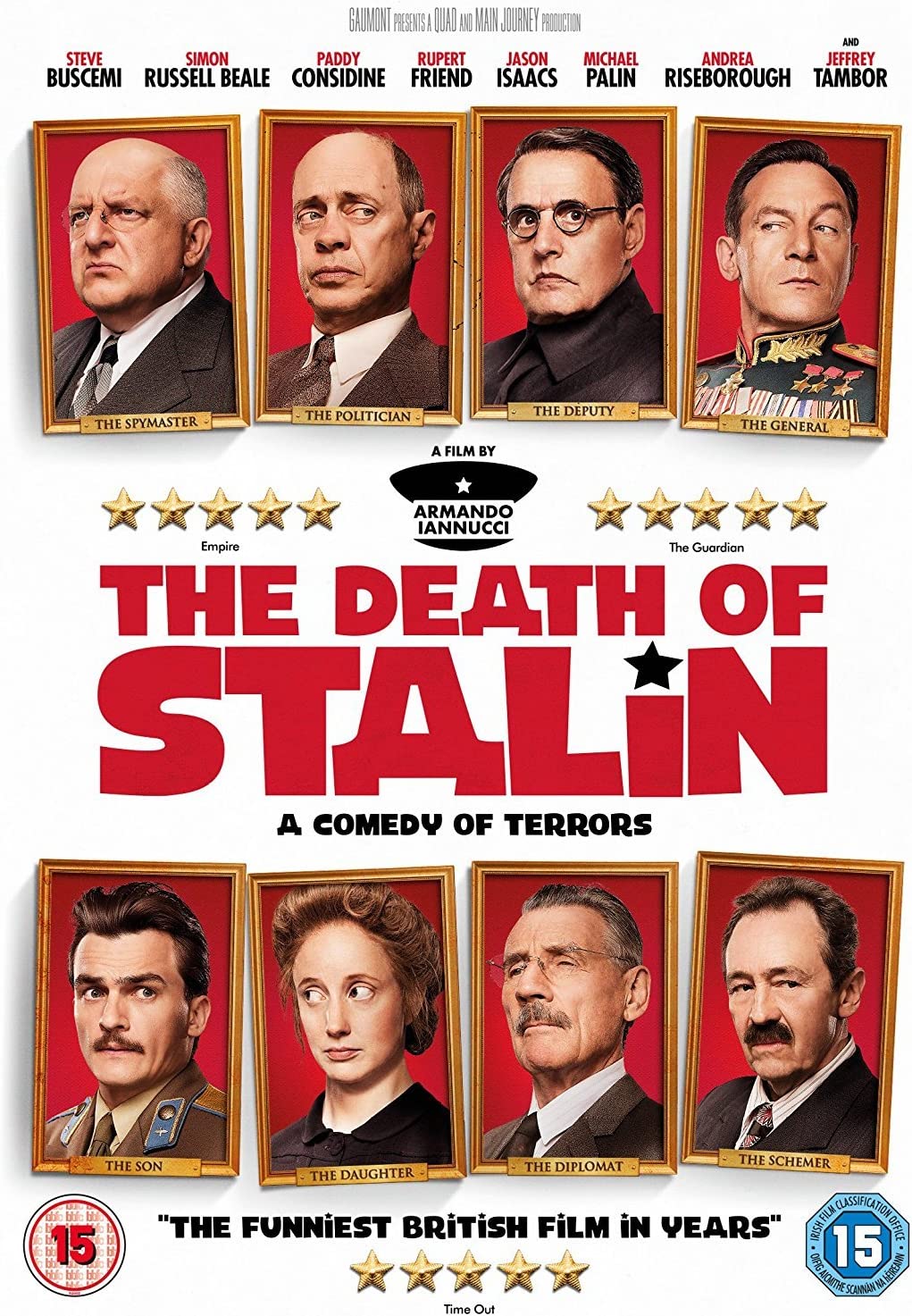

The Death of Stalin, 2017, dir. Armando Iannucci, adapted by Iannucci, David Schneider and Ian Martin from the French graphic novel series by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin, eOne Films/Gaumont, UK release October 2017, 107 minutes.

This review was commissioned by and published in Standpoint magazine, December 2017, where it may be read here. The following is the unedited version.

I was intrigued to see this succès de scandale. It had been called ‘revolting’ by the Russian Communist Party, and ‘disgraceful’ by Peter Hitchens. According to some it reflected on Putin, whilst according to David Cameron it reflected on Theresa May. It was praised as Iannucci’s deepest work, and condemned as a grosss lapse from form. It has not yet received a Russian license, and it grossed twice in its opening weekend what In the Loop did in 2009. I went fully prepared to hate it and walk out.

In the event, I stayed in my Everyman armchair to the credits’ end, so may now toss my own ha’pennyworth into the furor.

First the facts. Insofar as they are known about such a fact-averse period, this stylised comedy is surprisingly close to them. This is largely thanks to the graphic novel on which it is based (not merely ‘inspired by’, as the blurbs have it) – Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin’s 2017 La mort de Staline. This writer-illustrator duo has clearly read the eyewitness accounts, such as Khrushchev’s 1960s memoirs and Svetlana Alliluyeva’s ‘Twenty Letters to a Friend’.

Khrushchev’s recollection that the doctor eventually summoned to Stalin’s deathbed touched his hand gingerly, before being roughly ordered by Beria to take it properly, is reproduced exactly in a couple of the comic’s frames. The novel’s madly-orthodox Molotov is a fair reconstruction from the interviews that Molotov himself gave to Soviet journalist Felix Chuev between his forced retirement in 1962 and his death in 1986, in which he castigated Khrushchev and Beria as non-Communists, praised Stalin for his terror (‘of the three who spoke at the funeral, I was the only one who spoke from the heart’), and described the Cheka leader Felix Dzerzhinsky as ‘a radiant, spotless personality’. These interviews were published in the Soviet Union in 1991, just in time to give inspiration, if not success, to the coup plotters of August 199l – and in plenty of time to give inspiration to this novel.

Iannucci’s satiric genius might have seized on other moments of Soviet history: the similarly-fraught power struggle after Lenin’s death, the late 1980s succession of gerontocrats, the botched coup against Gorbachev, or Brezhnev’s senile pomp; but these subjects do not likewise have well-researched comic novels to hand.

That said, the novel’s relative fidelity to its sources has not bound Iannucci with equal fidelity to the novel. The latter’s mild liberty of portraying Zhukov as young (which he was not) as well as a lantern-jawed and large (which he was), is magnified many times by the film’s casting of Zhukov as a swaggering Jason Isaacs with chest padding and a Yorkshire accent. In fact, Zhukov had been exiled to the provinces by Stalin out of jealousy at his post-war popularity, but was called by Khrushchev and his co-conspirators to be one of the military leaders led by air defence commander General Moskalenko to arrest Beria. Khrushchev recalls that he was the first to enter the room at Malenkov’s pre-arranged signal: ‘“Hands up!”, Zhukov commanded Beria’. In the film, he is the commander of the Red Army and leads the plot to destroy Beria.

Jason Isaacs as Marshal Zhukov

The novel observes the three months that elapsed between Stalin’s death and Beria’s arrest; the film comically exaggerates the Politbureau’s competitive disarray by having this take place in a matter of days. Rather than being tried by a military court, as he probably was, he is lynched and burned by his colleagues, which he certainly wasn’t. The film makes comic capital out of Orthodox priests’ presence at Stalin’s funeral by Beria’s invitation; the novel rightly does no such thing. As Khrushchev recalls, after Stalin’s cerebral hemorrhage two days before his death, the Orthodox Patriarch and Chief Rabbi of Russia were ordered to say prayers for him. After all, it had been Stalin himself who had repermitted religion in Soviet life.

The film also exaggerates the role of the Christian anti-Stalinist pianist Maria Yudina, to the point of making her write a note to Stalin denouncing his crimes, and making this the cause of Stalin’s stroke. This makes no sense on its own terms; a character intended to be positive should not risk the lives of her innocent employers. Nor did she play at Stalin’s funeral; Richter did. I suspect that her role was exaggerated in order to include one person of moral backbone; but Stalin’s daughter Svetlana, whom the film makes a cracked comic counterpart to her dissolute brother, might have played this role more realistically. Yudina’s role is also, let it be noted, made worthy of a former Bond-girl; at least Olga Kurylenko, who is Ukrainian, is the one person in the film who can pronounce Russian names.

The film, not the novel, implies that Khrushchev was given a raw deal in being asked to organise Stalin’s funeral; on the contrary, it was an honour. Stalin had organised and spoken at Lenin’s funeral, as he reminded people throughout his life.

As far as the film’s interpretation of Stalin is concerned, it is worth recalling the fraught history of his reputation. Non-Soviet Communists, as well as anti-Communists, had denounced his crimes well before his death, as Orwell’s 1945 Animal Farm exemplifies. Inside the USSR, Khrushchev led the way with his (not very) secret speech to the 1956 Twentieth Party Congress, which expanded the blame for the crimes of the Terror and Gulag beyond Beria – on whom it had been concentrated since 1953 – to include Stalin himself. This speech denied him a significant role in the Soviet victory over Naziism, leaving the military to claim this as its own.

Thereafter, however, renewed claims have been made for Stalin’s significance as a wartime leader – in England by historians such as Geoffrey Roberts; in the Soviet Union, with the effect of provoking Khrushchev to write his memoirs as a counter.

In the West, Stalin has remained a source of debate between some left- and right-leaning people over his equivalence or otherwise to Hitler (Peter Hitchens asked, in response to this film, ‘whether anyone would think the final days of Hitler, the other great European mass-killer, torturer and tyrant, would make a good comedy, with Goebbels, Himmler and the rest of the Nazi elite played for laughs. No, of course not’).

In Russia during the 1990s, Stalin became the focus of patriotic nostalgia for some of those who were suffering most at the time, even whilst testimony to his crimes was encouraged by NGOs such as Memorial, and an increasingly-powerful Orthodox Church. He is now a focus of admiration particularly amongst Communists (the largest opposition party by far, with around 20% of the public’s support compared to 2% for the West-leaning parties combined), the elderly, and Georgians. The several hundred Stalin monuments that have been restored in the post-Soviet period, and the very few that have been built new, are predominantly local initiatives on the part of elderly people, or else are in Georgia. Stalin’s image in Russian society as a whole is therefore tensely in the balance between Communism-saving defeater of Hitler, and monster. At the same time, a less fraught version of this dispute rumbles on in the West.

The film implicitly dismisses Stalin as a wartime leader by the simple expedient of making Zhukov a hero (albeit one caricatured beyond, I would imagine, the patience of his many admirers). The most-quoted line in the film is Zhukov’s: ‘I fucked Germany. I think I can take on a flesh lump in a waistcoat’ (which is dubbed in the Russian trailer as: ‘I took Berlin; somehow I’ll manage with a fatty in a pince-nez’). We see Stalin only in the last days of his life, at which time even disciples such as Molotov admitted that he was ‘not completely in control of himself’. It has even been suggested that he had a stroke in 1948, which led to a personality change, and to the increasingly contemptuous treatment of his Politbureau of which Khrushchev so vividly complains.

But we hardly even see this; we hardly see him at all. We get little sense of the man who would call his colleagues to the Kremlin when he rose in the afternoon, conduct state business in the intervals of films that he would put them through, drag them to boozy all-night suppers at his dacha, then send them to their morning’s work. If Khrushchev was self-serving in representing Stalin as the perverter of a system, and he and his colleagues as his victims (‘the abuses of Stalin’s rule were not committed by the Party but were inflicted on the Party’), then the film, which otherwise owes so much to his memories, is having none of it.

Malenkov, Khrushchev, Beria, Mikoyan et al are represented as facilitators and confrères, whose careerism (a major sin in the Soviet catechism) and collusion in moral and intellectual madness becomes painfully exposed when their lynchpin is removed. Their lack of unity is indicated by their crazy range of accents: Khrushchev has a Brooklyn accent, Malenkov a Californian one, Mikoyan and Stalin are Cockney, whilst Zhukov is a Yorkshireman; this is in no way intended to represent the actual range of accents on the Politbureau.

So Iannucci takes the system at its own word. In theory there was no King or President, merely the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In that case, he suggests, the responsibility was collective.

As Molotov lamented of A. Avtokhanov’s (Paris-bought) book Enigma of Stalin’s Death, which his interviewer had given him to read and comment on: ‘He depicts us all as a gang of brigands!’. So does this film.

Admittedly, the clearly most evil character is Beria – the one who, in the words of Peter Bradshaw, ‘puts the warhead on the satire.’ He is shown about to rape a woman arrested for the purpose (though not in the act, unlike the novel, which shows him raping a child over his desk). But he is merely the nastiest. He is not shown as having the peculiarly close relationship to Stalin that existed during the preceding years (Khrushchev recalls: ‘When Beria and Stalin fought, Beria could always pretend it was just a lovers’ quarrel. When two Georgians fight, they’re just amusing themselves. They’ll always make up in the end.’) Beria’s colleagues are not shown as shocked – as they were, and as was Svetlana – by the way in which Beria spoke contemptuously of Stalin whilst he was unconscious after his hemorrhage, then fell to kiss his hand the moment he revived. They are shown as colluding in Beria’s crimes – and in that the film is right, even if the full extent of their horror, including the rape of over a hundred girls and women, only emerged after he was arrested.

The result is that Khrushchev (played by Steve Buscemi) comes out of the film rather less well than the novel, let alone Khrushchev’s own memoirs; the film will do little to revive his reputation from the low point it has stood at – in Russia as well as outside of it – ever since his displacement by Brezhnev in 1964. If T.S. Eliot refused to publish Animal Farm on the grounds that it was Trotskyist, this film could not similarly be called Khrushchevite.

Having said that, given the alternatives, the audience is pleased to learn from the film’s concluding surtitles that Khrushchev finally wins the power struggle in 1957. He is shown as sincere in his desire to liberalise, in clear contrast to Beria. But the film does not give him his due to the extent of noting that, when Brezhnev ousted him in his turn, he was not imprisoned or killed in large part because of the culture change that he himself had brought about. He had broken a tradition of conducting Russian power struggles stretching back centuries. When in 1957 Molotov and Malenkov launched a Stalinist coup which failed, they were expelled from the Politbureau, and a few years later from the party, but were not otherwise hurt. No Russian leader has lost their life with his office since then, and such assertions as are occasionally made that Putin holds onto office out of fear are implausible.

So much for fact. Now for value. Peter Hitchens, in his sharp formulation of a point made by many, argues that: ‘We are so free and safe that we can hardly begin to imagine a despot so wholly terrifying that his subordinates are even afraid of his corpse. This trivial and inaccurate squib does not help us to do so’; ‘misery, pain, fear and mass murder are milked for feeble giggles.’

Certainly, the film is guilty of misusing humour on occasions, although not quite as Hitchens suggests. The woman who sparked the ‘Doctor’s Plot’ conspiracy theory by denouncing her Jewish colleagues is referred to by Beria – who has just described her previous fellatio of him and others – as ‘lady suck-suck’. This elicits a knee-jerk laugh, but it is Beria’s joke, and in laughing the audience is sharing his humour. An orchestra member, when told of the need to dampen the acoustics for a music recording demanded by Stalin at short notice, suggests inviting his wife because she is ‘so fat’; this is a surprisingly lumpen and passé form of humour. ‘I don’t think any of these people have heard of Mozart’, comments the music director about the proletarians hauled in off the streets to be audience members. Yet, since Soviet education had been in existence for three decades by this point, the claim is unlikely. Indeed, the conductor dragged from his bed to make the recording in his dressing gown provides an unintentional visual metaphor for the Soviet Union’s imposition of high culture on the mass of the people, however crudely dressed.

The swearing for which Iannucci’s characters are famous, and which I find tiring even when at its exuberant wittiest, has here degenerated into ‘fucks’ spread across all characters indiscriminately. This is not just unfunny, but an unjustified lapse from fact. Tony Blair may have imported bad language into Downing Street and thus into Iannucci’s oeuvre, but 1990s London is not 1950s Moscow; Russian taboo language is far stronger than its English equivalent and consequently less used, as the Russian translation of Zhukov’s boast indicates. Stalin swore on occasion, because he could, but in this he was the exception. As a result, the film’s Politbureau members appear cruder and less educated than they were, and the important differences between them are eliminated (Khrushchev was palpably less educated than his peers, and always painfully aware of it).

I sympathise with Hitchens’ implied irritation at those responses to the film which demonstrate the modern servility towards comedy. According to the forelock-tuggers, everything is appropriate material for humour, everyone should be able to take a joke, the only criterion on which funny things should be judged is their funniness, and comedy has sacred rights but no duties. For those who feel Stalin’s crimes the most strongly and personally, this comic film might be painful watching best avoided.

Where I part company with Hitchens is on his claims that the film is useless to those with no prior understanding of these crimes, and that Iannucci milks the horror itself for cheap laughs. This is because I perceive something that he, in common with those who have praised the film as comedy gold, seem to have missed. The gold is mixed with the blackest tar – such as ran through the Lubyanka, the construction sites of the White Sea Canal, the Kolyma Gulag, and Moscow’s House on the Embankment, where NKVD staff regularly called at four in the morning.

It is acceptable to mix comedy with such terror and pain because, the film persuasively suggests, there was a terrible comedy intrinsic to the insanity of Stalin’s system. As long as the comedy is intrinsic to the terror, rather than being a varnishing and obfuscation of it, it is not only acceptable but points to a truth. The preface to the graphic novel, after the usual disclaimer of artistic license, ends: ‘Having said this, the authors would like to make clear that their imaginations were scarcely stretched in the creation of this story, since it would have been impossible for them to come up with anything half as insane as the real events surrounding the death of Stalin.’

Take, for example, Khrushchev’s account of Beria’s arrest. It was planned that Malenkov, who chaired the Presidium of the Council of Ministers at which it took place, would call first on Khrushchev and then on other members to speak. They would all accuse Beria in turn, Malenkov would propose a motion to arrest him, this would be carried, Malenkov would press a button, Zhukov and his fellow marshals and generals would enter the room, and Malenkov would order them to arrest Beria. In the event, the last person to speak was Mikoyan, who suggested that Beria would surely appreciate the comradely criticism that had been offered, reform his ways, and continue to be useful. During the perplexed silence which followed, Malenkov lost his nerve. So Khrushchev took the floor to propose the vote, at which Malenkov, panicking, and without waiting for the vote, pushed the button, and ordered the arrest in the tiniest of voices. At this point the conspirators realised that they didn’t know where to put Beria, since all of the prisons were under his control (he was eventually transferred to a bunker at Moskalenko’s headquarters). It seems incredible that the planning would be so lax, but Khrushchev had nothing to gain from making this up.

Or take an event which neither the novel nor the film depict. Immediately after Beria’s arrest, the Politbureau went to the Bolshoi to attend the première of Yuri Shaporin’s The Decembrists. At every interval in this opera about a coup which failed at considerable cost to its plotters, they dashed out to make phone calls to discover whether or not Beria had staged a counter-coup, before returning to their seats to try to sit impassively through the next part of the performance. The first indication that the public received of Beria’s fall was when Pravda listed the Politbureau members present at the Bolshoi, and Beria’s name was not there.

There is humour in both incidents, but a humour inseparable from terror, which is not funny at all. The film is wise to this, and is itself in many places emotionally iridescent. It raises uncertain laughs, which are suddenly cut down. It moves from a hilarious scene of the meeting convened after Stalin’s death, to a mass execution which is messily halted by the delivery of a Politbureau decree. The comedy here is not so much black as ice-cold and pale. Beria’s discomfiture at his undignified arrest arouses the viewers’ triumphal amusement, until the arrest turns into a lynching, and the comedy quickly sickens. A rueful laugh is raised by the closing surtitle informing the audience that Khrushchev is eventually toppled in his turn, but over the final credits people are wiped out of photos one by one, to Shostakovich’s music.

The film’s origins in a graphic novel are apparent, but unlike other acted (as opposed to animated) film adaptations of comics, it embraces the paradoxes of that transition: the intrinsically cartoonic played out by real flesh and blood. Whereas much satire takes external phenomena and exaggerates them, this film seems to reach inside for the noumenon of the situation, and then depicts that externally. It is for this reason that the characters are so unrealistic; they are the inside turned outwards (just as, arguably, Molotov turns himself inside out in his memoirs). Stalin’s coffin did indeed have a transparent bubble above his head so that his face could be seen, but in this the literal coincides with the metaphorical. The coffin looks as though dreamt up by a cartoonist to satirise the fear of Stalin’s ability to spy into the souls of men even in death.

Stalin’s coffin, with a transparent bubble above Stalin’s head

Such troubled comedy requires and receives confident performances. To me the standout is not the much-praised Simon Russell Beale’s Beria (he is good, but this is a relatively straightforward villainous part), but Jeffrey Tambor’s hilariously witless Malenkov, and Andrea Riseborough’s bizarrely bizarre Svetlana.

Jeffrey Tambor as Malenkov

Between them, the ensemble produces some purely comic moments, such as when Stalin is dying and pointing at picture of a lamb being fed from a horn. This happened, and Khrushchev seems unaware of the comedy in his account of how he had immediately expounded to the others what this meant. The film permissibly broadens this into a hilarious contest of interpretations between competing Politbureau members. Another gag is the ongoing search for a small girl with whom Stalin once posed, in order that she can appear with Malenkov at the funeral. Once they have at length established that they want a girl who now looks like that girl did then, not the same girl, and once they have found and obtained such a girl, it turns out that only her hand can be seen waving at the crowds over the Kremlin parapet. But for the most part the humour is adulterated. Responsibly so.

Such humour can best be understood in relation to this film’s major model, The Great Farewell (Великое Прощание). This is a seventy-five minute film of Stalin’s funeral and related ceremonies on the occasion of his death which splices purpose-shot colour footage with black and white newsreel. It was intended for general release, but was dropped because of Beria’s fall (he could not easily be excised from it), and was in the end only released after the Soviet Union had ended.

Its influence on Iannucci’s film is palpable: the details of the coffin and the room in which it stood, the Politbureau members standing by, the photogenic little girl, Beria’s dress sense and movements. Stalin’s son’s funeral speech in the Iannucci film, in which he hilariously cycles through the names of all the Soviet republics, may have been inspired by The Great Farewell’s iterated tours of Soviet capitals in which ceremonies are taking place, glossing the country concerned when this might not be known (for example, ‘Tirana – capital of Albania’).

In parts, The Great Farewell is moving. The geographic spread of the grief at Stalin’s death is awesome. The soundtrack is a compilation of grief-heightening classics from Grieg, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven and Chopin. For all the choreography, genuine grief is on display. It is moving to see North Korean soldiers on their battle front, evidently disorientated at the sudden loss of one of their supporters. The emphasis is far less on the Politbureau members, who occupy relatively little screen time, than it is on the masses. And although the reverse is true of The Death of Stalin, it resembles The Great Farewell in its respect for that grief; in the modern film there is not a hint of ridicule of their desire to pay their respects, nor of their paying for this with their lives (1,500 were killed in a crush caused by the security forces).

On the other hand, at many points The Great Farewell makes one feel slightly sick. It is pompously mournful, rigidly deferential, and has constant voiceover in praise of Stalin. Individuals attract the camera’s eye in proportion to the demonstrativeness of their grief, but it is striking that nobody tries to linger for even an instant as they shuffle at fair pace past Stalin’s coffin. Such discipline carries with it the suggestion of severe compulsion; and these thousands of queuers are clearly habituated to queuing. The red banners bearing black and white portraits of Stalin unfortunately recall the Nazi colour scheme. This is particularly chilling in the footage of them being carried in their thousands through central Warsaw. The wreaths laid at the foot of the Kremlin wall, which stretch out of sight into the distance, eerily recall the German banners which were laid there eight years before – as though the people’s grief itself were a trophy of Stalinism. One of the Bishops – of all people – is shown crying.

So, if this makes one feel sick, then The Death of Stalin is the vomit. Iannucci tears back the thick pall of mourning to say ‘cheer up! You’re better off without him!’ As C.S. Lewis knew when he wrote The Screwtape Letters, sometimes the right response to Satan is to laugh at him.

But this devil is a historic one, and the film is a specimen of that rare genre, satire of the past. Satire is nearly always directed at the present, whenever it is set; this film is an exception. Of course, anything can acquire resonances with events as they transpire. Thus it was that Iannucci, on a day off filming to attend the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, described the film to David Cameron, also in attendance. He recalls that Cameron ‘could barely contain his surprise and horror and joy at how the film’s story paralleled exactly what was going on in Downing Street.’ Since then, the film has acquired resonances with the situation in Saudi Arabia. If any insecure members of its royal family were to watch it, they might have a similarly uncomfortable reaction as Stalin’s colleagues when he showed them an English film about a pirate captain who eliminated his fellow pirates one by one (after first pinning their photos to his cabin wall). The Death of Stalin might return to mind should there be a power struggle after Putin leaves office. But such homologies are post facto and accidental. The film itself is as firmly directed towards late Stalinism as was Animal Farm, which was rejected by most English publishers as being too clearly about Stalin, a wartime ally, rather than dictatorship in general.

Given all this, I am hopeful that the film will be granted a license in Russia. After all, permission was evidently granted to film it there, and Stalin’s Kuntsevo dacha and Beria’s residence were either actually used for shooting, or for the research necessary to make highly convincing reconstructions of them. Much was made in Britain of Pavel Pozhigailo’s comment that the film was a ‘planned provocation’ aimed at angering Russia’s Communists; a ‘western plot to destabilise Russia by causing rifts in society’, which might therefore be banned. But he, it turns out, is only a junior advisor to the culture ministry.

It might be asked how many Russian films British cinemas show, and how tolerant the British government or people would be of a Russian satire on, say, the death of Churchill, or fall of Margaret Thatcher. Would this not, in the current climate, be denounced as Russian interference in British politics? The fact that the coverage of Russian responses to this film has fed into the currently prevailing Russophobia was sadly evident in the abusive graffiti I spotted on one of the ubiquitous London Underground posters for the film: ‘Fuck Russia’.

But if it is to be granted a Russian license, then why has this not happened yet? There are various sensitivities to be considered, including those of Stalin’s victims as well as his fans. During the War, the British and Americans felt able to caricature Hitler as a funny little mustachioed man with one ball, whereas Soviet propaganda – understandably, given the scale of Soviet losses – treated him only as a death-hungry monster. Similarly, Stalin is someone that the Russians, who are so much closer to him than we, are inclined to take soberly, whatever their perspective on him. Once, when out drinking with friends on the streets of Moscow, one of them told me severely to put away my beer bottle when we came to Red Square, ‘because it’s sacred’. That kind of no-messing attitude towards the epic convulsions of Russian history that have taken place on the square may militate against the film’s popularity.

It may also not help the film’s reception that it is English, given the current British political hostility towards Russia, of which Russians are well aware. In this respect the film may be more contentious than the current Russian succès de scandale Matilda (concerning Nicholas II’s relationship with ballerina Matilda Kseshinskaya, although the Church has more reasons to oppose this than The Death of Stalin, having canonised its protagonist).

All of these issues are all the more sensitive now, at the centenary of the Revolution. The government has had to tread a careful line in its commemorations between the feelings of the Orthodox and of Communists, and it might well consider it prudent to wait with this film (which may be disliked by both these sizeable constituencies) until next year. But I hope, then, that it will be permitted – both because there is no good reason to ban such a film anywhere, and because it is a remarkable film. And I wish for Russians that they can move beyond the trauma of the presence and the loss of Stalin, to the point when Iannucci’s genius for conveying the comedy of past insanities can be appreciated without unbearable pain.