Versions of the following lecture were given annually as a lecture at New College of Humanities, on the Applied Ethics course taken by all third years, between 2013 and 2017. This latest version dates from 2017. Clips from 24 and Zero Dark Thirty were shown.

CLIP: 24 – Fox Network, Season 5 [January-May 2006], episode 12, 6-7 pm, 21 minutes

How many of you know the television series 24?

I wouldn’t expect it to be that many, because of your age.

24 is a Fox Television series, aired in eight 24 hour seasons from 2001-10, with one film in 2008, and a final 12 episode series in 2014.

Insofar as it has entered public consciousness beyond its fan base, it is for the controversy that has surrounded its scenes of torture, of which we have just seen an example.

In this scene we saw the series hero, Jack Bauer, an agent of the fictional agency CTU LA, Counter Terrorism Unit, Los Angeles, order the chemical torture of Christopher Henderson, a former head of CTU LA, now the head of Omicron International, which makes nerve gas.

As Bauer has worked out, Henderson hired the assassin who killed the former President, because he had begun to find out about the new President’s plot, in collaboration with Henderson, to supply nerve gas to Chechens in order to justify US military intervention in the Caucasus, to the end of securing cheap gas supplies for the United States.

Much can be said about this scenario. I’m not going to say any of it. Rather, I’m going to talk about this scene.

The most important is perhaps this. Whereas some of the torture that Jack Bauer carries out is done on the road, on the hoof, with what comes to hand or his bare hands, in this scene the torture being carried out in the medical interrogation room of CTU, which exists for this purpose. 24 is therefore set in a parallel America in which torture is quotidien, unremarkable, and legal.

But since it aired during the 2000s War on Terror which followed the September 11th2001 attacks, it implicitly acknowledged and justified what was increasingly becoming known, that torture was practised by US officials and their proxies internationally.

This in itself is unquotidien, and remarkable. In modern history, that is to say since torture was criminalised in most Western countries – to the significant exclusion of their colonies – in the eighteenth century, not one of these cultures has celebrated the activities of its professional torturers in its culture. Such would not only have been unthinkable in the conservative Hollywood of the Cold War 1950s, but in Stalin’s Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany. Notwithstanding that both these latter tortured abundantly, torture was no part of the virtues that were attributed by and to the state in its self-representation. On the contrary, if torture was represented it was perpetrated by enemies, the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany, as the case might be. And this has long been the pattern of popular representations of torture; that it is the threat posed to our own, to James Bond, by the other, not as practised by ourselves on the others. What happened in America after September 11th2001 was not only a sharp increase in the representation of torture in American culture (before it, fewer than four acts of torture appeared on prime-time television each year; afterwards, it rose to over a hundred), but there was a reversal in the identity of the torturers, from invariably the enemy, to frequently the self.

France’s crisis with terrorism, the Algerian War of 1954-62, produced a famous novel by ex-paratrooper Jean Lartéguy called Les Centurionsor The Centurions, in which torture is represented as giving life-saving information at a crucial moment in the plot. But torture is not represented as normal or legal; it is the exceptional product, on the ground, of a bloody guerilla war. In 24, set at home in what passes for peacetime in this fictionalisation of the United States,it is a mere counterpart to the death penalty as actually practised. The quasi-cruciform gurney to which Henderson is tied is identical to that on which lethal injection is administered. So, with this series more than in any other cultural product of the War on Terror, a boundary is being crossed.

There were other reasons why 24’s torture scenes, of which there were 67 in the first 5 day-long seasons, were controversial.

The torture was nearly always successful in generating life-saving truths (as it happens, not in the case of the clip that I showed you), in distinction to actual torture To invert a recent assertion of President Trump, anyone who believes that torture works, quote, ‘is stupid’.

Tony Lagouranis, a former US Army interrogator said: ‘“In Iraq, I never saw pain produce intelligence,” “I worked with someone who used waterboarding” “I used severe hypothermia, dogs, and sleep deprivation. I saw suspects after soldiers had gone into their homes and broken their bones, or made them sit on a Humvee’s hot exhaust pipes until they got third-degree burns. Nothing happened.” Some people, he said, “gave confessions. But they just told us what we already knew. It never opened up a stream of new information.” If anything, he said, “physical pain can strengthen the resolve to clam up.”’

All the torture in 24 is in the context of the ticking time bomb scenario, in which the torturer knows that the victim has information about the location of a bomb, nerve gas or whatever, and that it will be revealed if tortured out of him, and that if it is not revealed many lives will be lost. This is the intrinsically fictional scenario central to justifications of torture since 2001.

Bob Cochran, who created the show with Joel Surnow, admitted that “Most terrorism experts will tell you that the ‘ticking time bomb’ situation never occurs in real life, or very rarely.” End quote. Rather, the conceit of the ticking time bomb was first popularised by its appearance in the French novel I mentioned before, “Les Centurions.”’

Of course, the ticking time bomb scenario is a logical impossibility, because of the certainties that it involves. But there are other respects in which the torture in 24is merely improbable. Neither Jack nor his victims are ever traumatised by the experience. When it is done in error to a good guy or girl, it serves to bring them even closer to Jack. There is no time, in the implausibly-packed real time of the 24 hour season, for anyone to do anything other than act. There are rarely lasting injuries, meaning that the torture falls outside the much tighter definition of torture promulgated by Assistant Attorney General Jay S. Bybee in August 2002: ‘‘equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death”.

The torturer, though like James Bond frequently a truant to his own organisation, is utterly good. He loves; agape for humans, and a respectful eros towards women. He exhibits no pleasure in torture, and in one episode falters in doing so at the screams of his victim. This compassion is sharply reprimanded by events; his colleague saves the day by stabbing the victim’s knee, at which he blurts out the location of a nuclear bomb due to go off in LA. The hypothesis of the good torturer who, Christ-like, takes sin on himself in order that we may be saved from sin as well as death, is instrinsic to the ticking time bomb scenario, and as fictional as it.

Jack imposes torture increasingly frequently and strongly over the first six seasons, as its entertainment value diminished through the habituation of the viewer, therefore mirroring the ‘creep’ with which torture is often practised, on the part of an individual torturer, and a country. Torture was eventually reduced, and the series itself ran down, as much because it had become repititious as because the social and political climate of the United States had turned away from torture to a degree by the time the series ended in 2010.

Finally, the show provoked debate by containing negligible debate about the acceptability of torture. The one, telling exception was the 4th season in 2005, in which a barely fictionalised Amnesty International called Amnesty Global secures the release of a suspected terrorist. Fortunately Jack resigns from CTU in order to distance his actions from his colleagues, kidnaps the man, and breaks his hands, thereby acquiring vital and accurate leads.

Many defenders of the torture in the series did so on the grounds of its applicability to reality. These included many members of and people close to the government. Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, who participated in the 2006 Symposium ‘24’ and America’s Image in Fighting Terrorism: Fact, Fiction,or Does It Matter?”’ praised the show’s depiction of the war on terrorism as “trying to make the best choice with a series of bad options.” He said “Frankly, it reflects real life.”

Executive Producer Howard Gordon described Washington’s enthusiasm for the show as ‘very heavy’, and Roger Director, Surnow’s friend, joked that the conservative writers at “24” have become “like a Hollywood television annex to the White House. It’s like an auxiliary wing.’

On the other hand, those defenders of the series who did not wish to defend torture argued that the series was clearly fictional, indeed fantastical, and therefore did not ask to be related or applied to reality. Rush Limbaugh, when asked about the show’s treatment of torture, responded, “Torture? It’s just a television show! Get a grip.”’ The claim of the show’s fantasicality is indisputably true. The plots are outlandish even by the standards of actual American foreign policy. Events repeatedly shape themselves into classic, philosophy-tutorial ethical dilemmas. The paranoia – that even the President of the United States can be a traitor – far exceeded what was then conceivable but has generated fictions in the present (I should here say that I consider the current accusations of President Trump of treachery are not paranoid but as calculatedly political as unevidenced). The naivety of the exposition and fantasy of conception have a childlike quality; one sometimes wonders how far it knows and delights in its own absurdity, such as when a torture victim strapped to a gurney is wheeled frantically around CTU during a chemical gas attack, thus confusing the torture and the terrorism which it was meant to have prevented, and which it at many levels resembles.

In these respects and others 24 is Trumpian. Presidential candidate Trump made the campaign promise to ‘bring back a hell of a lot worse than waterboarding’, said that one must fight fire with fire, and that those contemplating attacks on civilians quote ‘deserve it anyway’. Like 24 he assumed torture’s efficacy and moral acceptability, and did so in a completely unselfconscious, unashamed, non-eupemistic way that characterised neither Bush nor his officials, with whom the series and the height of American torture are contemporary. 24’s qualities as genial, somewhat goofy entertainment are shared with President Trump, as are its non-interventionist politics. The rogue president in Season 5 is contemplating sowing chaos in a Caucasian country in order to commandeer oil; President Trump, to a bewildering chorus of liberal criticism, announced that America would no longer go around the world deposing foreign leaders. In 24the trouble happens at home, often as blowback from American exploits abroad.

But if President Trump’s pro-torture pronouncements, which he himself has qualified by saying that he will defer to the relevant officials and the law, have some of the same showiness and fantasicality as the 24 show, they may have some of the same effects. There is no such thing as, as Limbaugh put it, just a television show, or just art of any kind. Even though CIA Director Mike Pompeo and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have ruled torture out, Trump’s performances may influence behaviour in actual American prisons at home and abroad. Likewise, it is overwhelmingly likely that 24 led to actual torture as perpetrated by those American operates around the world amongst whom 24 was favoured viewing.

As Tony Lagouranis put it simply “People watch the shows, and then walk into the interrogation booths and do the same things they’ve just seen.”’

In November 2006 U.S. Army Brigadier General Patrick Finnegan, the dean of the United States Military Academy at West Point, flew to Southern California to meet with the creative team behind 24. Finnegan, who was accompanied by three of the most experienced military and F.B.I. interrogatorsin the country, arrived on the set as the crew was filming. At first, Finnegan—wearing an immaculate Army uniform, his chest covered in ribbons and medals—was taken for an actor and asked what time his “call” was.

In fact, Finnegan and the others had come to voice their concern that the show’s central premise was having a toxic effect. In their view, the show had adversely affected the training and performance of real American soldiers. “I’d like them to stop,” Finnegan said of the show’s producers. “They should do a show where torture backfires.”

Gary Solis, a retired law professor who designed and taught the Law of War for Commanders curriculum at West Point, told me that he had similar arguments with his students. He said that, under both U.S. and international law, “Jack Bauer is a criminal. In real life, he would be prosecuted.” Yet the motto of many of his students was identical to Jack Bauer’s: “Whatever it takes.”’

Before the meeting, Stuart Herrington, one of the three veteran interrogators, had prepared a list of seventeen effective techniques, none of which were abusive.’

‘After Howard Gordon, the lead writer, listened to some of Herrington’s suggestions, he slammed his fist on the table and joked, “You’re hired!”

Tony Lagouranis told the team that “rapport-building,” the slow process of winning over informants, is the method that generally works best. There are also nonviolent ruses, he explained, and ways to take suspects by surprise. The team seemed interested in the narrative possibilities of such techniques, but at the same time, worried that such approaches would “take too much time” on an hour-long television show.’

I’d like for now to leave 24 and turn to a very different artistic response to the War on Terror

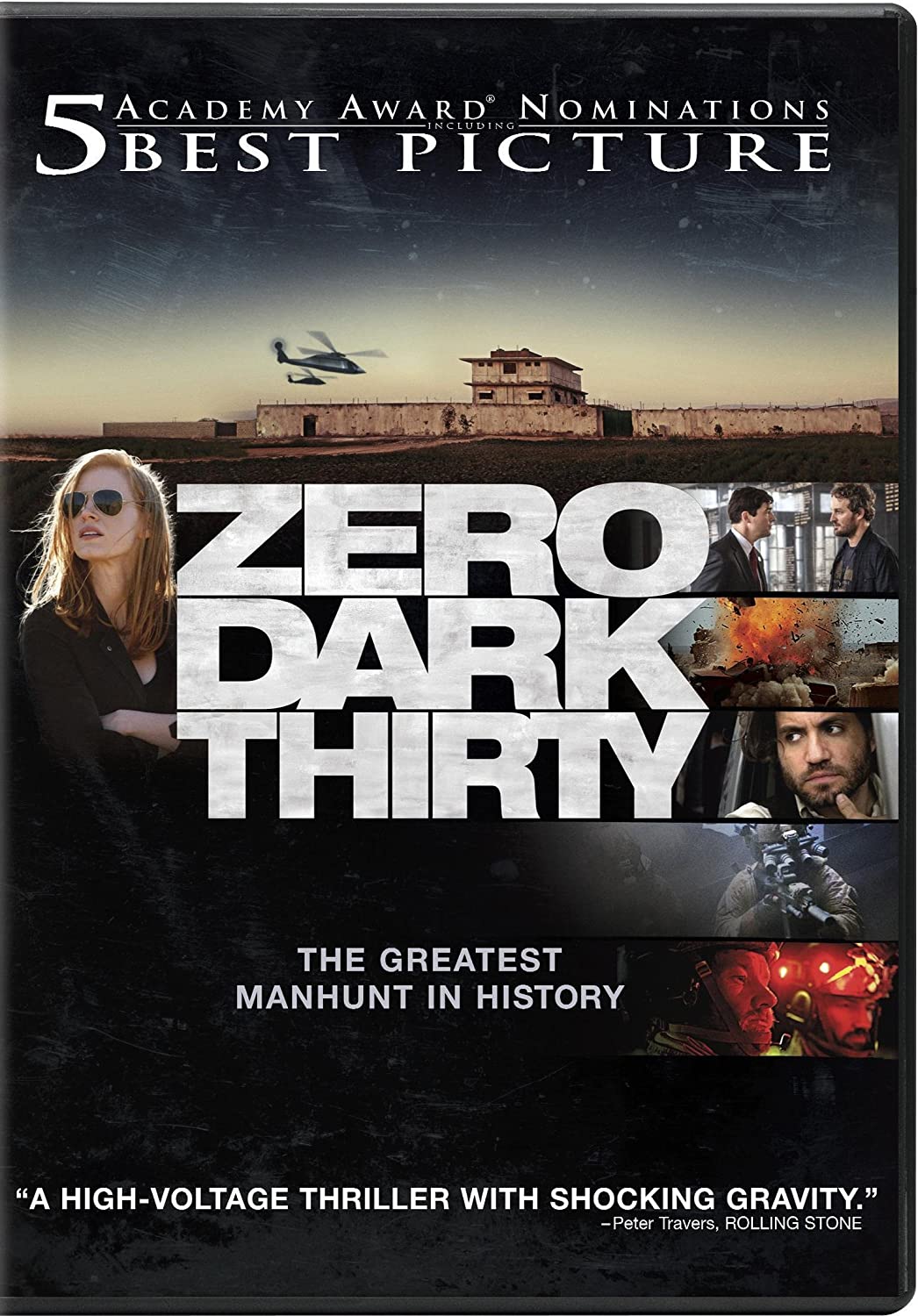

Zero Dark Thirty

For those of you who haven’t seen it, it is a Hollywood film released in December 2012 concerning the tracking down and murder, in the May 2011, of Osama Bin Laden by American forces. In four scenes torture is shown; in three others it is implied.

Here is one of them, from near the beginning of the film:

[ZDT CLIP]

15.33-43, 18.30-22.32 (a violent interrogation).

The film too was controversial for its treatment of torture, but in a far more complex way, since opinion was split on what this would-be historical film’s attitude towards torture actually was.

The debate therefore focuses on questions both of fact and value.

The facts: whether or not the torture as represented resembles the events which actually occurred in the search for Bin Laden.

The values: whether or not the events as they actually occurred should have been represented; whether or not the torture in the film, truthful or otherwise, was presented in a way which tried to justify it; and whether or not the film, if it did present torture in a way which tried to justify it, should have done so.

All sixteen permutations of two answers to these four questions are possible, though some are commoner than others.

And there is one further issue of value, which we saw also in the case of 24.

Some critics argue that the film’s status as fictional absolves it of responsibility to fact orvalue. They either elevatethe film into the aesthetic realm, or diminish it into that of entertainment – each realm with its supposed independence from history and morality.

The Chicago Tribune film critic Michael Phillips described it as ‘a must-see despite the CIA’s recent criticisms of its accuracy.’ Mark Bowden, the author of Black Hawk Down,said that this was ‘not journalistic but a Hollywood movie.’ It was widely praised as a well-made action film.

Yet, if this type of criticism were the only kind, then the film would have grossed far less than the 140 million dollars it has to date, the debates to which it denies relevance having been responsible for much of the film’s publicity; 24, by contrast, I think would have been as successful had it aroused no controversy surrounding its depiction of torutre. Even before it was launched, US senators had accused the film of endorsing torture; the film’s director Kathryn Bigelow, its writer, Mark Boal, and its leading actress, Jessica Chastain, had responded in its defence.

The last two of the film’s three official trailers built on this, opening with voiceover from the CIA torturer Jack: ‘Can I be honest with you? I am bad news […] I’m going to break you’

Bigelow was proud of the fact that her film had stimulated a debate on torture, which had already – it has to be said – been lively.

But she also said that:

‘I find it interesting that you could see Zero Dark Thirty and in any way come to the conclusion that it is pro-harsh tactics. It’s absolutely inconceivable. Certainly, my feeling going in was: if we don’t examine some of the more regrettable acts that transpired in the name of finding Osama Bin Laden, we’re going to repeat them’.

That is, she both wanted her film to stimulate debate about torture, and not to be interpreted as supporting it. Rather, she was nonplussed by those who interpreted the film in a different way to her.

I think that Zero Dark Thirty split its interpreters for these reasons:

Whereas 24 did not orientate itself towards historical fact, ZDT emphatically did so.

A surtitle appears near the beginning: ‘The Following Motion Picture is based on first-hand accounts of actual events’.

It starts with real audio footage from 9.11. ‘I’m going to die, aren’t I? No no no no. It’s so hot, I’m burning up.’

The exact nature and efficacy of the precise torture alluded to is not common knowledge, and viewers’ individual knowledge and assumptions concerning these affect their interpretation of the film’s facts, and therefore of its values.

Finding the film to exaggerate the usefulness or diminish the brutality of the torture involved in the search for Bin Laden is likely to correspond to a position of endorsing torture – and the reverse.

But even bracketing out historical fact, the film has rhetoric, which is judged in relation to one’s own prior attitudes. Those most strongly opposed to torture are most likely to see the film as pro-torture, those most supportive of it are most likely to see it as critical or neutral.

Bigelow’s bewilderment that her film could be interpreted as pro-torture confirms, Iwould argue, the respects in which it is. And these are many.

Torture is shown to be an intrinstic part of the extraction of the name of Abu Ahmed (Bin Laden’s courier) from several prisoners. Another detainee, after being threatened with rendition to Israel, pleads:‘I have no wish to be tortured again. Ask me what you wish and I will answer’. It is as though he is pleading simultaneously with two sets of torturers; he is appealing to the CIA with his offer of information; and with his confession of the efficacy of torture he is appealing to the film’s creators for mercy.

In fact this is not how the information was extracted to get the name of Abu Ahmed. .

U.S. Senator John McCain, who was tortured during his time as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, said that the film left him sick – “because it’s wrong”. In a speech in the Senate, he said, “Not only did the use of enhanced interrogation techniques on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed not provide us with key leads on bin Laden’s courier, Abu Ahmed, it actually produced false and misleading information.”[76]

McCain and fellow senators Dianne Feinstein and Carl Levins ent a critical letter in December 2012 to Michael Lynton, chairman of the film’s distributor, Sony Pictures Entertainment, stating, “[W]ith the release of Zero Dark Thirty, the filmmakers and your production studio are perpetuating the myth that torture is effective. You have a social and moral obligation to get the facts right.”

The Senate Intelligence Committee’s torture report December 2014 sheds new light on how the CIA created and then continued to protect its false claim that it found Osama bin Laden in part because of its abusive interrogation tactics.

The report presents detailed evidence based on reviewing millions of pages of CIA documents that the identification of bin Laden’s courier who was eventually found to be living with the al-Qaeda leader in the Abbottabad compound had nothing to do with the CIA torture program.

FBI official Ali Soufan knew about bin Laden’s courier, Abu Ahmed, in 2002 through informants, detective work, tailing, and surveillance on Guantanamo Bay detainees.

And in revealing the new details about what the CIA knew and when it knew, the report documents for the first time the extraordinary mendacity of the CIA’s senior managers in seeking to hide the truth from Congress, senior cabinet officers and the public.

Moreover: torture produces lies.

In 2003, both then-US Secretary of State Colin Powell and then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair made the same argument for the invasion of Iraq – that Saddam Hussein was supporting Al-Qaeda.

However, a 2008 Pentagon report found that information was false, and there was no connection between Saddam’s regime and the terror group.

In 2014, the US Senate’s intelligence committee said “evidence”had been extracted from a prisoner under torture “as a justification for the 2003 invasion of Iraq.”

The claim by Libyan detainee Ibn Sheikh al-Libi was recanted on the basis that it was made under torture,“and [because he] only told them what he assessed they wanted to hear.”

From Bagram, al-Libi is believed to have been rendered to Egypt, where he was further tortured, before ultimately ending up in Libya, where he disappeared.

“This was directly cited by Bush in October 2002, and again by Colin Powell in the UN, as one of the major justifications for war.’

So torture is falsely presented as leading to the murder of Bin Laden, rather than as leading to the falsehood on which the invasion of Iraq was justified, and which motivated much of the torture perpetrated by American soldiers in Iraq, according to their own testimony: they believed they were paying back the destruction of the Twin Towers by torturing Iraqis.

The tortures shown – strap-hanging, darkness, loud music, near-drowning, and confinement to a box – are shown briefly and therefore shown asbrief, and are by a long way not the worst of the tortures committed by Americans in that period, which also include music torture, faked executions, forced nakedness for days on end, sexual humiliation, staring into bright light, sitting on hot surfaces, induced hypothermia, doing push-ups with guards standing on prisoners’ backs, being allowed only two bathroom trips a day and being left soiled, guards urinating on prisoners, men and women prisoners being raped by penises, rifles, and fluorescent lights, electric shocks, breaking of bones, and beating to death.

The proportion of useful to wrong or useless information generated by actual torture is about fifty-fifty – hence certain misguided appraisals of the film as balanced.

The torturers Jack and Maya are unambiguously the film’s moral heroes, and focalise its narration. Only once is the camera alone with a prisoner strapped to the ceiling of a dark room filled with aggressive music, and that only for a couple of seconds before the torturers enter. The torture chamber sets feel unpleasant, but safe; viewers are only required to take a small imaginative step into them from the safety of the cinema, not the giant leap that would be required for empathy with the prisoner. Every new location to which a lead has directed the next investigation and next scene of the film, is identified to the viewer by subtitles – but presumably not to the prisoners who find themselves extraordinarily rendered there: for example ‘CIA Black Site, Gdansk, Poland’ – an extraordinarily cheerfully candid acknowledgment of the existence of black sites. (at the beginning of the film we have ‘Black site. Undisclosed location’).

Revulsion from torture is at first embodied in Maya, and then, suggestively, shown as being overcome by her. Early in the film we see her watching torture live; later we see her watching it on tape, suggesting that she has become distanced from it and is doing what we are doing – watching a film for its plot. Her beautiful face – remember that of Audrey Raines, Jack Bauer’s colleague looking on during the clip from 24? – is intercut with the ugly footage, contrasted to rather than implicated in it.

A later torture scene in a CIA black site in Gdansk, Poland – she has got used to it, and so have we.

Later still in Pakistan a prisoner says explicitly: ‘I have no wish to be tortured again. Ask me a question again and I will answer it’

We aren’t given it again and again, because that would get wearing, as indeed it is wearing to be tortured again and again. The comfort of the viewer is taken into consideration.

Her colleague Jack retires from Afghanistan once the torture has got too much for him but there is no suggestion that he is traumatised. Maya remains, and is stressed – but entirely by her failure to find Bin Laden, not by the torture. Former Guantanamo guard Brandon Neely criticised Zero Dark Thirtyfor not representing the effect of torture on the interrogators.

One other crucial atypicality of the film, which it has in common with 24, is that it excludes internal CIA debate on the acceptability of torture. Jane Mayer of the New Yorker amongst others has pointed out that there was considerable opposition to torture within the CIA in the early 2000s. References to opposition to torture – from President Obama, are glimpsed on television, provoking the film’s heroes to lament people being ‘lawyered up’, and to say ‘As you know, Abu Ghraib and Gitmo fucked us’. That is, by failing to include debates abouttorture, it fails to debate torture.

Rather, it endorses torture, in an insinuating way that is sometimes mistaken for openness to debate. Unlike 24, which merely outraged people who were disposed to condemn torture, it makes concessions – that torture can yield false information, that other investigative and interrogative methods are at least as useful, that prisoners can retain some dignity despite torture, that the political climate has turned against torture, that it can be unpleasant and stressful to inflict, and that it should be performed as certain Christian theologians have argued that the rather disgusting act of sex should be performed – never for pleasure, or its own sake, but as the means to an end. And, as with sex, if the end is not achieved every time, it is absolved by the fact that the spirit in which it was performed was the right one.

I would not in fact say that Jack and Maya are indicated as taking visceral pleasure in their torutre. Jack has a facetious manner which is part of his interrogational strategy but when off duty shows no enthusiasm for torture. Maya is the more obsessive torturer, but in a stressed, angry, and goal-orientated way. Yet it is possible for a filmto take such pleasure, even whilst, superficially, treating torture soberly.

This was journalist Michael Wolff’s suggestion, when he described Bigelow as a “fetishist and sadist” who made history an excuse for: ‘the total sexiness of physical abuse.’ Similarly, Slavoj Žižeksuggested that were a similar film to be made about a brutal rape or the Holocaust, it would “embody a deeply immoral fascination with its topic, or it would count on the obscene neutrality of its style to engender dismay and horror in spectators.” He is, I would argue, wildly optimistic about likely reponses to treatments of brutal rape – but I also think that both his suggestions are wide of the mark in relation to this film. I do not think that it is fascinated with torture, nor as Wolff suggests, with its sexiness. Nor does it have an obscene neutrality of style, since depictions of torture can never be even stylistically neutral.

Rather – the film is not only well-made from a cinematographic point of view, as critics have universally acknowledged, but is highly rhetorically proficient. Its ability to depict acts which commonly cause revulsion without losing viewers’ sympathy for the perpetrators is true not only in relation to the torture, but most remarkably in the climactic invasion of Bin Laden’s compound. Several unarmed women as well as men are shot; children look on and cry as their parents are killed; the marines appear monstrous in night vision goggles, each eye shooting green light in two directions – and yet the film’s sympathy remains firmly with them, and their agenda. As Jane Mayer comments: ‘If [Bigelow] were making a film about slavery in antebellum America, it seems, the story would focus on whether the cotton crops were successful.’

Now, almost every story ever told has been focalised through or on a subset of its characters. Telling the story of the events which preceded Bin Laden’s murder from the point of view of CIA officers is a legitimate thing to do. The torture which they inflict is by definition the overwhelming concern of the prisoners, whilst they themselves have the physical liberty to entertain another concern, which is the discovery of Bin Laden. However, the film falls squarely into a genre – the police procedural. Within this genre, the discovery of the target fact of BL’s location is of overwheming importance at the joint level of plot (fact) and value (rhetoric). But life as lived – and most especially as lived within pressing constraints, such as were experienced by CIA officers in the early 2000s – defies genre. Torture would not have meant as little to its perpetrators as the film’s genre permits it to suggest. I do not argue that any film of any pretention to factuality which contains torture, must have torture as its central theme. But insofar as it is present, it must be allowed to have its existence as the moral evil which it inevitably is. The film’s obvious comparandum, Pontecorvo’s 1966 film Battle for Algiers, does this to a far greater degree – whilst doing the inverse of Zero Dark Thirty, making conditions tough for its anti-torture sentiments by presenting FLN atrocities, and deeply felt colonialist sentiment.

Maya and her viewers both witness torture, then, trying to work out whether a prisoner is telling the truth. The critically active viewer is in addition trying to work out how truthful the film is being, or what rhetorical strategies it might be using to manipulate us. This requires not hitting the film, nor twisting it (recalling the etymological origins of torture in torque), but in calmly interrogating it, and comparing the stories which it tells with what we have verified as fact from other sources. And, having done this, we can pass judgment, and welcome the fact that of the five Academy Awards and four Golden Globe Awards for which it was nominated it gained only one of each – for Sound Editing and Best Actress respectively.

I would say to the film as Maya says to her prisoners: ‘You can help yourself by being truthful’. Because when it comes to historical torture, art lets nothing off the hook.

So if 24 is the War on Terror show for President Trump, is ZDT the show for President Obama?

After all:

The murder of Bin Laden was hailed as one of the great successes of Obama’s period of office

The film was originally slated for release a month before the 2012 presidential election. Ended up being released in December 2012; Obama was elected in November 2012

Obama when he came to power in 2009 officially halted the Detention and Interrogation Program. He also prohibited EITs, saying on TV ‘we don’t torture’.

But torture was a felony and a treaty violation before and after the “banning”

He continued to outsource torture to other countries through rendition, and probably black sites.

He maintained power of the President to order torture

He used testimony produced by torture in US courts

Torture was used at the tail end of the search for Bin Laden under Obama. The Senate Intelligence Committee’s torture report December 2014 sheds new light on how the CIA created and then continued to protect its false claim that it found Osama bin Laden in part because of its abusive interrogation tactics.

[The Senate’s executive summary concludes that the CIA’s use of so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques” was not effective and did not produce any “unique” and “valuable” intelligence — in other words, information that the CIA would not have been able to obtain through other means.]

Guantanamo Bay. By February 2009 reports were coming that torture there was getting worse. It included “beatings, the dislocation of limbs, spraying of pepper spray into closed cells, applying pepper spray to toilet paper and over-forcefeeding detainees who are on hunger strike.”

The Obama administration never prosecuted anyone for their involvement in the torture program, and blocked attempts by former detainees to sue in civil court. Would rather not prosecute others for something that he is doing himself. Obama halted release of other photos

Human rights advocates warned at the time that the Obama administration’s decision could lead to a future president reviving the practice. According to recent research, support for torture never exceeded 50 percent in the Bush era. Since 2009, however, a majority has thought it should be allowed. The shift is most pronounced among Republicans: In 2004, only four in ten Republicans supported it. By 2012, eight in ten did. Candidate Trump played to that growing segment of his base on the campaign trail.

This fits with Obama era CIA helping in the making of the film.

As a result of a Freedom of Information request, it was revealed in May 2015 that in 2008 the CIA opened a liaison office with Hollywood.

Paul Barry, a CIA “entertainment industry liaison officer” said that, “Hollywood is the only way that the public learns about the Agency.”

Leon Panetta, the Director of the CIA under President Obama from 2009 to 2011, personally offered to help Boal with obtaining information from the CIA while writing a screenplay and gave him classified information about the bin Laden raid.

He gave Boal access to CIA personnel and facilities less than a month after bin Laden was killed in order to “further his research” for the ZDT screenplay.

Boal invited to attend the CIA’s classified bin Laden awards ceremony “held inside a large tent” outside of the main entrance of CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. It was attended by about 1,300 people.

“The audience was a mixture of both overt and covert personnel from across the Intelligence Community, as well as personnel from DOD and Congress. [Navy SEALs] who conducted the [bin Laden] raid were also in attendance,” the CIA inspector general’s report said.

At least 10 CIA National Clandestine Service (NCS) officers “identified as involved in the hunt” for bin Laden and other CIA officials would go on to meet with Bigelow and Boal, and work on the ZDT script.

The ‘Maya’ officer met with Bigelow and Boal.

Bigelow and Boal gave CIA officers gifts and bought them meals at hotels and restaurants in Los Angeles and Washington, and got agency officers and officials to review and critique the ZDT script.

The Senate Intelligence Committee launched an investigation in January 2013 into contacts between the CIA and the makers of “Zero Dark Thirty”, but dropped it a month and a half later.

“In the wake of ‘Zero Dark Thirty,’ CIA has completely overhauled its procedures for interaction with the entertainment industry. Among other things, the Agency created a centralized record-keeping system for entertainment industry requests and, in 2012, issued comprehensive, new management guidance on contacts with and support to the entertainment industry.”

Though they complained:

Michael Morell, the C.I.A.’s acting director, sent a public letter on December 21, 2012 to the agency’s employees, which said that Zero Dark Thirty ‘takes significant artistic license, while portraying itself as being historically accurate” and that the film “creates the strong impression that the enhanced interrogation techniques that were part of our former detention and interrogation program were the key to finding Bin Ladin. That impression is false. (…) [T]he truth is that multiple streams of intelligence led CIA analysts to conclude that Bin Ladin was hiding in Abbottabad. Some came from detainees subjected to enhanced techniques, but there were many other sources as well. And, importantly, whether enhanced interrogation techniques were the only timely and effective way to obtain information from those detainees, as the film suggests, is a matter of debate that cannot and never will be definitively resolved.[78]]

24

So, let us return to 24.

Both shows were prophetic.

24 was in many ways prophetic. It was not planned for the War on Terror. It was developed before the 11thSeptember 2001, but by the time it was aired on November 6 2001, not two months after the terrorist attacks, events had produced themselves in conformity to its paranoia, and thereafter it and the War on Terror fed off each other.

ZDT was to have been about how Osama slipped through their fingers in the immediate aftermath of 9.11

Then Mark Boal started working on a new film with Kathryn Bigelow

Two thirds of the way through the writing of the screenplay, Bin Laden was killed. The whole thing was rewritten.

The currently-showing [2017] reinvention of 24, 24: The Legacy, was planned before Donald Trump had won the Presidency, but its first episodes were aired fifteen days after his inauguration [Premiere 5.2.17]

It is astonishingly faithful to the style and spirit of the original. It has different central characters, but we are still at CTU LA, vast dangers, usually from foreign Muslims, tumble over each other within a day, obviously good people are actually extremely evil, American overseas adventures blow back to the homeland, ethical dilemmas crystalise within ten minutes, the credit sequence lists Jihadi #1, Jihadi #2, etc., and the exhuberance, naivety, lack of trauma, Chechen subplot, and music are the same.

There is no torture, however. So far at least – four episodes have aired so far; the fifth is appearing on Fox UK in less than two hours, at 9.00 pm – the bad guys do the torturing, the mob of a man called Bin-Khalid mob in search of a McGuffin which turns out to be a memory stick.

Here we are ten minutes into the first episode, and a presidential candidate and his wife are on the campaign trail

Clip:

24: THE LEGACY

Episode 1, 5.20 minutes

Stop at the words:

‘Rebecca Ingram’,

– or Maya!

The actresses even look slightly similar!

Let us continue [until the cut to Carter]

So we are six months on from the ending of Zero Dark Thirty. Maya has certainly made a quick recovery; in fact we can be relieved at how untraumatised and pleased with herself she now is. And the 12 SEALs seem to have been slimmed down to six, but they are still all butch and bearded.

Indeed, Manny Koto, one of the programme’s creators, ‘had an idea that was not a 24 idea, but as we talked, we thought, wow, maybe we could roll up with this character who was based on a real story—the special ops team which killed Osama bin Laden, and then came back to the states, where their identities were obscured and had a tough time adjusting. That was the premise of the character’.

This CTU awards ceremony is the CIA Bin Laden awards ceremony June 2011 which ZDT writer and producer Mark Boal attended after Bin Laden’s murder May 2nd2011.

And so the animals looked from Zero Dark Thirty to 24, and 24 to Zero Dark Thirty, and wondered which was which. This latest production of the American culture industry combines the bravura with which Bush and his officials could not quite express themselves about torture, but which they admired in 24,and which is found now in Trump, with the ends-orientation and rhetorical distancing from torture of the Obama era. Truly, here is a television series for our tangled times.

Thank you.

THE TORTURE DEBATE AND ZERO DARK THIRTY HANDOUT

| 24 Season 5 Episode 12

60 minutes 2006 Fox Network Joel Surnow, Robert Cochran Director Kathryn Bigelow |

| ZERO DARK THIRTY

157 minutes Released December 2012 Columbia Pictures Writer Mark Boal Director Kathryn Bigelow (Title is military code for 00:30 a.m.)

|

Rush Linbaugh: [asked about 24’s treatment of torture]: ‘Torture? It’s just a television show! Get a grip!’ ‘America wants the war on terror fought by Jack Bauer. He’s a patriot.’

Joel Surnow: ‘Isn’t it obvious that if there was a nuke in New York City that was about to blow—or any other city in this country—that, even if you were going to go to jail, it would be the right thing to do?’

Roger Director: [conservative writers at 24 have become] ‘like a Hollywood television annex to the White House. It’s like an auxiliary wing.’

Brigadier General Patrick Finnegan, Dean of West Point: ‘I’d like them [the television’s producers] to stop. They should do a show where torture backfires.’

Tony Lagouranis, Army interrogator in Iraq War: ‘People watch the shows, and then walk into the interrogation booths and do the same things they’ve just seen.’

‘In Iraq, I never saw pain produce intelligence.’

Mark Bowden: ‘[P]ure storytelling is not always about making an argument, no matter how worthy. It can be simply about telling the truth.’ [‘Zero Dark Thirty is not pro-torture’, The Atlantic, January 3rd, 2013, accessed 27.5.19

Glenn Kenny: ‘a movie that subverted a lot of expectations concerning viewer identification and empathy’; ‘rather than endorsing the barbarity, the picture makes the viewer in a sense complicit with it’, which is a ‘whole other can of worms’.

‘Zero Dark Thirty: Perception, reality, perception again, and “the art defence”’ December 17th, 2012, accessed 27.5.19

Emily Bazelon: ‘The filmmakers didn’t set out to be Bush-Cheney apologists’, but ‘they adopted a close-to-the-ground point of view, and perhaps they’re in denial about how far down the path to condoning torture this led them’

‘Does Zero Dark Thirtyadvocate torture?’ Slate, December 11th, 2012, accessed 27.5.19

Naomi Wolf: ‘Your [Bigelow’s] film claims, in many scenes, that CIAtorture was redeemed by the “information” it “secured”, information that, according to your script, led to Bin Laden’s capture. This narrative is a form of manufacture of innocence to mask a great crime: what your script blithely calls “the detainee program” […] Like Riefenstahl, you are a great artist. But now you will be remembered forever as torture’s handmaiden.’

‘A letter to Kathryn Bigelow on Zero Dark Thirty‘s apology for torture’, 4thJanuary 2013, The Guardian, accessed 27.5.19

Jane Mayer:‘In her [Bigelow’s] hands, the hunt for bin Laden is essentially a police procedural, devoid of moral context. If she were making a film about slavery in antebellum America, it seems, the story would focus on whether the cotton crops were successful.’

‘Zero Conscience in Zero Dark Thirty’, 12thDecember 2012, The New Yorker, accessed 27.5.19

Glenn Greenwald: ‘pernicious propaganda’ ‘presents torture as its CIA proponents and administrators see it: as a dirty, ugly business that is necessary to protect America.’

‘Zero Dark Thirty: CIA Hagiography, Pernicious Propaganda’,14thDecember 2012, The Guardian, accessed 27.5.19