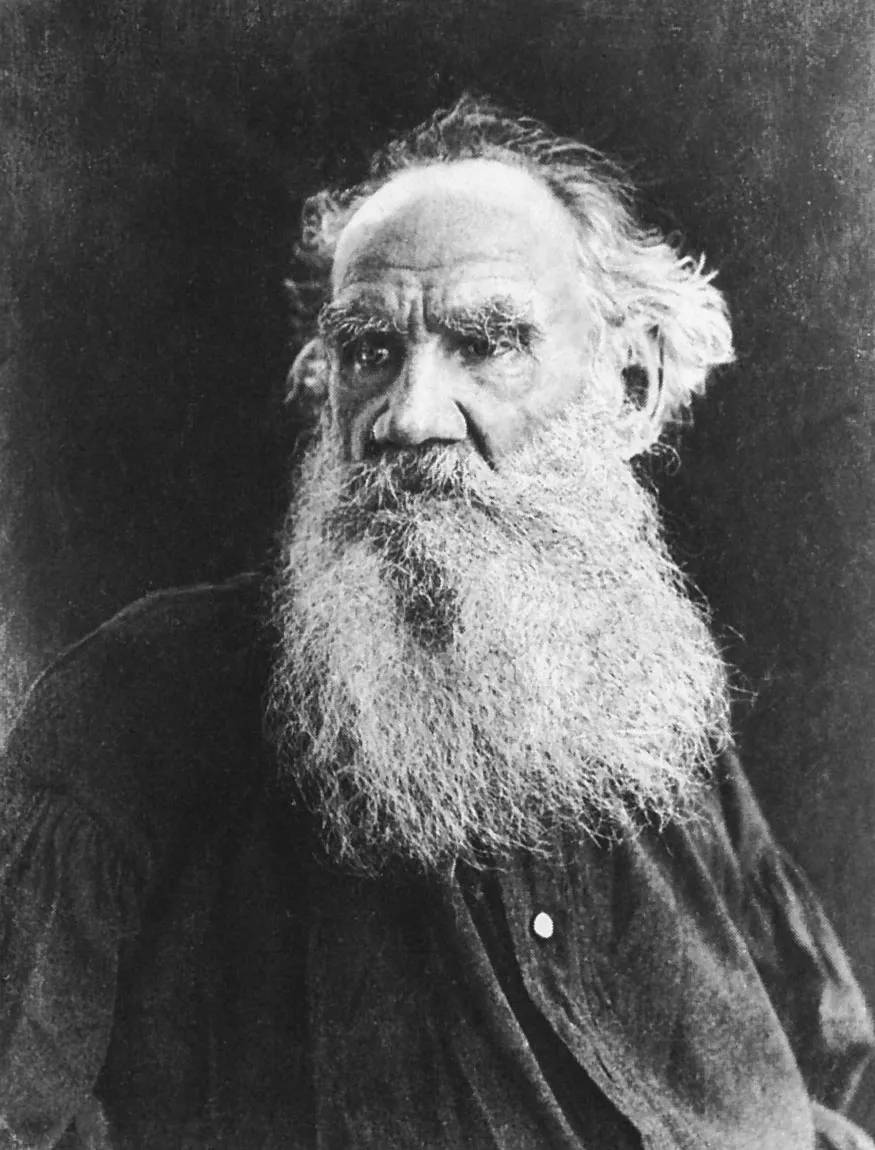

This paper was given at an international conference on Lev Tolstoy hosted by Tula University on the occasion of Tolstoy’s 190th birthday in September 2018.

In choosing a topic to speak on at this conference I found myself facing a problem. The obvious choice, as an English critic, was for me to speak about Tolstoy’s relationship to English literature, but his most sustained pronouncement on English literature is the 1903-4 tract O Shekspire i o Drame, which it is for several reasons difficult to say anything about.

This is the tract in which Tolstoy argues ‘that Shakespeare can not be recognized either as a great genius, or even as an average author’. He accuses him, especially in Korol Lir, of being unrealistic, artificial, lacking in technical mastery and historical consistency, unintentionally ludicrous, amoral, unreligious, and contemptuous of the masses. His opinion could not be further from that of the Romantics that he quotes, such as Shelley, for whom it was ‘the most perfect specimen of the dramatic art existing in the world.’ And it has not gone down well, especially in England.

The biographer AN Wilson in 1988 called it a ‘notoriously unsuccessful and somehow embarrassing attempt to dislodge Shakespeare from his pedestal’, ‘fifteen thousand words of nonsense’ and ‘almost Mephistophelian arrogance’, which stands in pathetic contrast to Shakespeare’s own late, great works.

Forty years earlier, George Orwell concluded his attack on the essay with the assertion that: ‘He turned all his powers of denunciation against Shakespeare, like all the guns of a battleship roaring simultaneously. And with what result? Forty years later [– we might now say 112] Shakespeare is still there completely unaffected, and of the attempt to demolish him nothing remains except the yellowing pages of a pamphlet which […] would be forgotten altogether if Tolstoy had not also been the author of War and Peace and Anna Karenina.’It ‘is not even an easy document to get hold of, at any rate in an English translation.’

That remains true today, as it is not of What is Art?, which is still in print in a Penguin edition.

So, is Tolstoy’s a boomerang criticism that flies back to knock him out in a most undignified way? Lear-like criticism forcing us into the position of a Kent: ‘See better, Tolstoy, and let me still remain/ The true blank of thine eye’. ‘Be I unmannerly when Tolstoy is mad’?

Not according to its defenders. Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov had anticipated Tolstoy’s criticisms, and the socialist realist critique of bourgeois incomprehensibility in art looked approvingly to Tolstoy’s essay; the Soviet critic MP Alekseev gives 16 pages of his 1965 monograph Shekspir i russkai︠a︡ kulʹtura to intelligently-respectful discussion of the essay’s anti-decadence and anti-formalism. George Bernard Shaw, the Edwardian critic Arnold Eiloart, G Wilson Knight and Ludwig Wittgenstein all admired its attack on snobbish veneration of Shakespeare as a thinker, realist or moral guide, making, as Arthur Symons said of What is Art?a ‘legitimate reductio ad absurdsum of theories which have had so many more cautious and less honest defenders.’ Orwell himself conceded that Tolstoy had landed some hits. Boris Pasternak, whose father was Tolstoy’s friend, deliberately translated King Learaccording to Tolstoyan principles of simplicity, unbuttoning and casting off precisely those elaborate metaphors that Tolstoy’s essay deplored.

Yet the essay poses considerable challenges to criticism. It is supremely iconoclastic. It courted, though didn’t quite meet, censorship, in attacking the author who had been used by Russian writers in the nineteenth century, and would be used by them again in the Soviet Union, as Shakespeare himself had used history – to avoid censorship. In doing so it engages at times in such vandalism of critical technique, that it rhetorically renders itself impervious to such techniques being used on it. With regard to exegesis, it has what Wilson Knight calls ‘so rock-like [a] simplicity’ that clarifications are redundant. The essay practices what it preaches in being crystal clear – if not to all peasants, then certainly to all critics. And as Tolstoy posits in What is Art?,critics are redundantif the artist ‘has by his work conveyed to others the feeling he has experienced: what is there to explain?’ Tolstoycan write about Shakespeare to argue that he has failed to communicate sincere feeling, but what does one do with Tolstoy?

Of course, ‘On Shakespeare and on Drama’ doesn’t present itself as art, but given its apparent ratio of emotion to ratiocination, it might be best to take it as such. But not to apply Tolstoyan principles of art criticism, but perhaps the kind of approach that is elicited by his compatriot,Vladimir Nabokov’s, Pale Fire. Written 60 years later, this book presents itself as an edited poem, but the poet is weak, the critic worse, and both are not only fictional but meta-fictional. The work’s exuberant satire on certain kinds of bad literary criticism inevitably renders the critic who approaches it extremely self-conscious. And that, to me, is one of the unintended effects of ‘On Shakespeare and on Drama’ – effects which are in fact, as Tolstoy demanded of all art, though not by the means he advocated, moral.

In a letter to VV Stasov of 1903, Tolstoy stressed that his essay concentrated less on ‘Shakespeare’s aristocratism’ than ‘the perversion, due to the praising of inartistic works, of aesthetic taste.’ Russian Shakespeareans had produced works that used Shakespeare’s characters as spiritual shorthand (Leskov’s ‘Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk Province’, Turgenev’s ‘Hamlet of Shchigrov District’ and ‘King Lear of the Steppes’, Nemirovich-Danchenko’s ‘A Village Ophelia’, and Zlatovratsky’s ‘A Village Lear’), which ran counter to the late Tolstoy’s aesthetic stipulations. But he particularly criticised the romantic criticism which had influenced them, and for which his ally Shaw had just coined a term – ‘bardolatry’. But as Wilson Knight points out, ‘the commentary had clearly influenced him. He looked for the praised qualities [such as realism of character] and found them absent.’

And so the mirror is flashed back to us, and how far we, in our response to any canonical and vogueish author, avoid on the one hand incremental contribution to praise that becomes unjustified, and on the other unjustified criticism of the author for failure to match such praise – and how clearly we distinguish, as Tolstoy does not sufficiently, critique of an author and of a critical discourse in which he or she is framed.

Tolstoy’s magnification of critical tendencies of which we may otherwise remain unconscious, applies to many other points.

For example, as a practitioner-critic he was judging Shakespeare adversely by the standards of the realism which dominated in his time, andfor example lay behind his recommendation to Stanislavsky to visit Tula region’s peasants in order to bring maximum verisimilitude to the Moscow Arts Theatre production of his 1886 tragedy The Power of Darkness. Simplicity of diction was politically-charged at the time, being opposed to the high-flown idiom employed by the official press, as well as by Shakespeare, and some of his romantic critics. So one is reminded of the aesthetic vogues that shape the criticism not only of practitioner-critics who have their own art to defend, but of all of us.

Tolstoy claims to have reread all of Shakespeare, aged 75, and to have read him over the decades ‘in every possible form, in Russian, in English, in German’. But for all his English reading and quotation (the essay frequently though not always quotes in English), it is apparent that there are gaps in his linguistic and cultural understanding – for example, he seems to miss the parody in Regan’s high-flown language when professing her love, which the Tolstoyan translator Pasternak also flattened, rendering her diction identical to Goneril’s. The heath on which Lear wanders becomes ‘steppe’, as it literally does in Grigori Kozintsev’s 1970 film, which was shot near the Sea of Azov and used Pasternak’s translation. And so English readers of Tolstoy’s essay become nervously aware of limitations to their own understanding of the contents and context of Tolstoy’s argument. Even Chertkov’s 1906 English translation, which Tolstoy had in view when writing the original, presents a different Tolstoy, since it sometimes gives Shakespeare’s original verse rather than Tolstoy’s Russian prose paraphrase.

Tolstoy’s revulsion from the cruelty of King Lear’s ending explains his preference for the 1594 True Chronicle History of King Leir and his three daughters, which was one of Shakespeare’s major sources. He doesn’t mentionNahum Tate’s 1680 adaptation of Shakespeare’s Lear; the 18thcentury Russian productions of Lear were based mainly on French and German, rather than English, adaptations. And by the time good translations from the English were being made, in the 1830s, Shakespeare’s Lear was itself returning to the English stage. But it seems likely that Tolstoy would have preferred it to Shakespeare’s, and for similar reasons to Alexander Pope, who in 1765 wrote approvingly of Tate’s dominance of the stage: ‘I was many years ago so shocked by Cordelia’s death that I know not whether I ever endured to read again the last scenes of the play till I undertook to revise them as an editor.’ Like Pope, Tolstoy makes us reflect on our own sensibility and preferences.

And also on our level of optimism. Tolstoy notes that King Lear has been one of the most highly praised of Shakespeare’s plays. After him, it was particularly popular in the twentieth century, second only to Othello on the Soviet stage. The Soviet critic Mikhail Morozov commented that ‘In the darkest days of the war, [Shakespeare] like a real friend, was with us”; in the wartime Tashkent production Goneril and Regan were likened to fascists, and it’s notable that it was Soviet Jewish theatres that presented this play the most during this period. Kozintsev, whose first production of the play was staged in Leningrad in 1941, called his second, 1970, production ‘A Lear of the nuclear age’. One senses that Tolstoy’s criticisms of the play’s unnaturalness, ostensibly a protest against its improbability, also protest against its possibility.

As Wilson Knight says, ‘Often as Tolstoy insists on the unnatural occurrences in Lear, he does not do so so often, nor so powerfully, as the poet himself.’

Then there is the fact that King Learwas close to the bone. Tolstoy had consistently criticised Shakespeare in every decade since the 1850s, but he had personal motivations to choose King Lear when he was in his seventies, and not just for the generic one summed up by Goethe as ‘Ein alter Mann ist stets ein König Lear’ (‘an old man is always a King Lear’). It seems likely that Tolstoy censured this play, rather as the English had banned productions of it during the madness of King George III, or as the regicide Catherine the Great had banned productions of Hamlet for nearly half a century, or as Stalin had Meyerhold killed soon after he commissioned Hamlet from Pasternak: the subject was sensitive.

Numerous critics have pointed this out: the Frenchman Robert de Michiels in 1914, the German Adrien Turel in 1931, George Orwell in 1947, George Steiner in 1959, Grigori Kozintsev in 1970, Harold Bloom in 1994 and Rosamund Barlett in 2010. These critics point backwards from ‘On Shakespeare and Drama’ to Tolstoy’s 1891 division of his estate, at which he actually told his children to go and read King Lear, through the growing tensions with certain of his family members thereafter, and forward to the moment when these tensions resulted in him leaving home with his faithful doctor, being joined by his faithful daughter, but eventually caught up with by those from whom he had fled, then dying in a stranger’s cottage.

Whether one wants to interpret Tolstoy’s end as tragic is another matter. William Nickell, in his 2010 book The Death of Tolstoy: Russia on the Eve, Astapovo Station, 1910, has analysed both the dramatic elements of Tolstoy’s flight and death, and the disputes over its genre: melodrama or national epic, Christian comedy or tragedy? His daughter Alexandra named her 1933 book-length account of the end The Tragedy of Tolstoy.

Steiner’s interpretation is that ‘there was in Tolstoy’s attacks on King Lear an obscure and elemental anger – the anger of a man who finds his own shadow cast for him through some black art of foresight.’ Certainly, he was refusing not only the general idea of tragedy, but this particular tragedy – rather as DH Lawrence and the older married woman with whom he eloped read Anna Karenina critically, wishing to avoid its protagonists’ fates.

Tolstoy’s passionate resistance to identification with a Shakespearean protagonist is the inverse of that self-identification which Turgenev’s ‘Hamlet of the Shchigrov District’ claims (by contrast, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and King Lear of the Steppe do not have the education – which is one of Tolstoy’s points about Shakespeare – to embrace or resist such analogies). This is, then, precisely the kind of personally-biased criticism which academia teaches us to avoid. And yet Tolstoy’s resistance is not just self-saving but morally motivated, since it was, arguably, his moral perception that had rendered him Lear-like in the first place. And though it is expressed backwards, in unsustainable criticisms of King Lear the play, it gives to the criticism a moral urgency that literary criticism often lacks.

For Tolstoy has similarities not just with King Lear the character but the play, and his resistance to the play’s ending may have accounted for his refusal to acknowledge what his affinities with it were. Swinburne, but not Tolstoy, praised the play for its ‘spiritual democracy and socialism’, which Kozintsev would bring out in his film version. ‘On Shakespeare and on Drama’ was designed as a preface to Shakespeare and the Working Classes by Tolstoy’s American disciple Ernest Crosby, which brochure – and the accompanying supportive letter from Shaw – misses the similarity. But when in 1953 Boris Livanov wanted to stage Lear,his chosen translator, Pasternak, wrote to him:

‘In Lear there is one eternal Tolstoyan note, and it is this. All that talk about kindness, fidelity, interests of the state and loyalty to the fatherland comes exclusively from scoundrels and criminals. The real heroes of the tragedy are a mad minor despot and a girl who loves truth to the point of sanctified folly. ‘Common sense’ is represented by beasts from a zoo and only these two are real human beings. The concept is supremely anarchic’.

But Tolstoy was, whilst writing ‘On Shakespeare and Drama’, also working on his own alternative to King Lear (both were begun in the 1880s, and reprised in the early 1900s). In The Light Shines in the Darkness the Tolstoyan protagonist Saryntsovtries to give away his wealth, and tells others to do likewise. He tries and fails to leave home, but his preaching leads one of his followers to incarceration and eventually a punishment battalion. Tolstoy did not finish the play, but in his notes for the ending the mother of this disciple shoots him in revenge, and he dies rejoicing the in knowledge that God can accomplish his will without him, and that he has understood the meaning of his life. Shaw saw this play as self-condemning. Aylmer Maude, rightly I think, stressed the Biblical context of the title: The Light Shineth in the Darkess, and the Darkness comprehended it not’.

This play is not only Tolstoy’s best response to King Lear, but it gives us the best clue as to how to interpret his prose response. The fact that he couldn’t finish the play, and instead finished the essay, may partly explain the latter’s anger. He had instead to live out the ending of the play, himself. I make no judgment as to the genre of its end. In the essay, he leaves the castle of Bardolatry, unbuttons himself intellectually, and exposes himself to the storm of criticism from Shakespeareans for all time – because he had his own emotional needs and moral projects to pursue, and he saw no other way. ‘None does offend, none, I say none’.

SHAKESPEARE IN NINETEENTH CENTURY RUSSIA HANDOUT

and the particular case of Tolstoy and King Lear

TIMELINE OF SHAKESPEARE IN RUSSIA 1700-1970

| DATE | EVENT |

| Early 1700s | Earliest French and German adaptations of Shakespeare |

| 1748 | First mentioned in Russia, by poet Aleksandr Sumorokuv.

Sumorokov adapts Hamletinto Russian from classicized French version by Jean Francois Ducis |

| 1762-1809 | Hamletbanned under Catherine II |

| 1767 | Department of translation set up in the Russian Academy of Science |

| 1786 | Catherine II writes version of The Merry Wives of Windsor: ‘What Comes of Having a Basket and Some Linen’ |

| 1820s | Shakespeare taken up by Russian Romantics and Decembrists.

Pushkin advocates that Russian theatre be modelled on Shakespeare, not Racine |

| 1825 | Kyukhelbekev, a Decembrist, translates Macbeth and Shakespeare’s history plays, and writes a study of Shakespeare, whilst in prison |

| 1830s | Anglomania in Russia, focusing on Byron, Scott and Shakespeare |

| 1837 | Polevoy translates Hamlet |

| 1848/9 | Turgenev writes ‘Hamlet of the Shchigrov District’ |

| 1856 | Tolstoy, who has recently learned English, declares that he does not like Henry IV |

| 1860 | Ivan Turgenev writes ‘Hamlet and Don Quixote’ |

| 1861 | Balakirev writes ‘King Lear Overture’ |

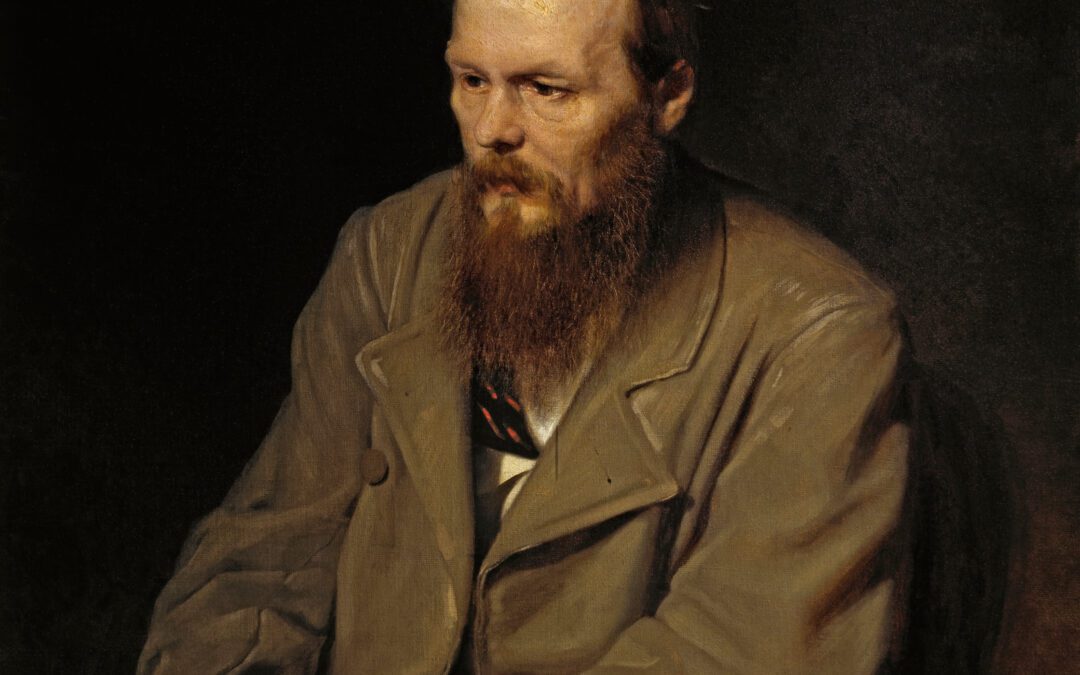

| 1864 | 300thanniversary of Shakespeare’s birth celebrated in Russia. Fyodor Dostoevsky writes Notes from Underground |

| 1865 | Nikolai Leskov writes ‘Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District’ |

| 1870 | Turgenev writes ‘King Lear of the Steppes’ |

| 1870s | Beginnings of a turn against Shakespeare in Russia |

| 1880s | Tolstoy begins his play The Light Shines in the Darkness |

| 1883 | Turgenev dies |

| 1890s | Second wave of Russian Anglomania |

| 1897-98 | Tolstoy writes ‘What is Art?’ |

| 1902 | Tolstoy abandons work on his play The Light Shines in the Darkness |

| 1903 | Tolstoy rereads Shakespeare’s plays |

| 1906 | Tolstoy writes ‘Shakespeare and the Drama’ |

| 1910 | Tolstoy dies |

| 1917 | Russian Revolutions. Bolshevik government makes Shakespeare central to the Soviet canon; all of Tolstoy unbanned (Marx had admired him).

Inter-war craze for Shakespeare in the Soviet Union |

| 1934 | Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk Districtperformed, then banned until 1962 |

| 1938 | Prokofiev writes the ballet Romeo and Juliet |

| 1939 | Boris Pasternak translates Hamlet(having been dissuaded from original writing 1936-50). Later translates 3 sonnets, 2 songs, 6 tragedies, and both parts of Henry IV

Meyerhold arrested whilst rehearsing a production of Hamlet |

| 1941 | Kozintsev directs King Lear |

| 1947 | Pasternak translates King Lear |

| 1954 | Grigori Kozintsev directs Hamlet |

| 1956 | Pasternak writes ‘Notes on Translations of Shakespeare’s Tragedies’ |

| 1962 | Shostakovich rewrites Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District as Katerina Izmailova |

| 1964 | Kozintsev directs film of Hamlet |

| 1966 | Katerina Izmailova filmed |

| 1971 | Kozintsev directs film of King Lear |

- Ivan Turgenev, ‘Hamlet of the Shchigrov District’ (1848/9)

trans. Constance Garnett as ‘The Hamlet of the Shtchigri District’ in A Sportsman’s Sketches, Volume II (1895-99)

‘In one of Voltaire’s tragedies,’ he went on wearily, ‘there is some worthy who rejoices that he has reached the furthest limit of unhappiness. Though there is nothing tragic in my fate, I will admit I have experienced something of that sort. I have known the bitter transports of cold despair; I have felt how sweet it is, lying in bed, to curse deliberately for a whole morning together the hour and day of my birth. I could not resign myself all at once. And indeed, think of it yourself: I was kept by impecuniosity in the country, which I hated; I was not fitted for managing my land, nor for the public service, nor for literature, nor anything; my neighbours I didn’t care for, and books I loathed; as for the mawkish and morbidly sentimental young ladies who shake their curls and feverishly harp on the word “life,” I had ceased to have any attraction for them ever since I gave up ranting and gushing; complete solitude I could not face…. I began – what do you suppose? – I began hanging about, visiting my neighbours. As though drunk with self-contempt, I purposely exposed myself to all sorts of petty slights. I was missed over in serving at table; I was met with supercilious coldness, and at last was not noticed at all; I was not even allowed to take part in general conversation, and from my corner I myself used purposely to back up some stupid talker who in those days at Moscow would have ecstatically licked the dust off my feet, and kissed the hem of my cloak…. I did not even allow myself to believe that I was enjoying the bitter satisfaction of irony…. What sort of irony, indeed, can a man enjoy in solitude? Well, so I have behaved for some years on end, and so I behave now.’

[…]

‘No, for mercy’s sake!’ he cut me short, ‘don’t inquire my name either of me or of others. Let me remain to you an unknown being, crushed by fate, Vassily Vassilyevitch. Besides, as an unoriginal person, I don’t deserve an individual name…. But if you really want to give me some title, call me… call me the Hamlet of the Shtchigri district. There are many such Hamlets in every district, but perhaps you haven’t come across others…. After which, good-bye.’

- Ivan Turgenev, ‘Hamlet and Don Quixote’ (1860)

trans. Moshe Spiegel (1965)

The first edition of Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamletand the first part of Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote appeared in the same year, at the very beginning of the seventeenth century.

This concurrence seems momentous.

[…]

In these two types, it seems to me, are embodied two contrasting basic tendencies, the two poles of the human axis about which they revolve. All men, to my mind, conform to one type or the other; one to that of Hamlet, another to that of Don Quixote – though it is true, no doubt, that in our era the Hamlets are far more common

[…]

It is unfortunate, however, that our conception of Don Quixote should be equivocal; only too often we substitute the name of Don Quixote for a jester; the term quixotismcarries the connotation of idealistic twaddle; where in reality one ought to discern Quixotism as an archetype of self-sacrifice.

[…]

What does Don Quixote typify? Faith, first of all, a belief in something eternal, indestructible – in a truth which is beyond the comprehension of the individual human being, which is to be achieved only through the medium of self-abnegation and undeviating worship.

Don Quixote is entirely permeated by an attachment to his ideal for which he is ready to endure untold misery, even to sacrifice his own life, if need be. His own life he esteems only insofar as it can serve his ideal, which is to instigate justice and truth on earth. It may be said that his deranged imagination draws upon the fantastic world of chivalric romance for his concept. Granted – and granted that this constitutes the comic side of Don Quixote. But his ideal itself remains undefiled and intact. To live for oneself, to be concerned with one’s own ego – this Don Quixote would regard as a disgrace. He exists (if one may put it so) outside himself; he lives for others, for his brethren, in and hope of neutralizing evil and to outwitting those sinister figures – sorcerers and giants – whom he regards as the enemies of mankind […] Serene at heart, he is in spirit superior and valiant; his touching piety does not curb his liberty. Though not arrogant, he does not distrust himself, nor his vocation, nor even his physical capacity. His will is a will of iron, and unswerving. The continuous striving toward one and the same goal has fixed the unvarying tenor of his thoughts, his intellect takes on a one-sided uniformity. Hardly a scholar, he regards knowledge as superfluous. What would it avail him to know everything? But one thing he knows, the main thing: he is aware of the why and wherefore of his existence, and this is the cornerstone of all erudition.

[…]

What, then, does Hamlet represent? Above all, analysis, scrutiny, egotism – and consequently disbelief. He lives wholly for himself, and even an egotist cannot muster faith in himself alone; one believesonly in that which is outside or above oneself. But Hamlet’s I, in which he has no faith, is still precious to him. This is the ultimate position to which he invariable reverts, because his soul does not espy in the world beyond itself anything to which it can adhere. He is a sceptic, yet always he is in a sir about himself; he is forever agitated, in regard not to his duty but to the own state of his own inward affairs.

Doubting everything, Hamlet pitilessly includes his own self in those doubts; he is too thoughtful, too fair-minded to be contented with what he finds within himself. Self-conscious, aware of his own weakness, he knows how restricted his powers are. But his self-consciousness itself is a force; emanating from it is the irony that is precisely the antithesis of Don Quixote’s enthusiasm.

[…]

Let us not be too exacting with Hamlet. He suffers and his suffering is more valetudinary, excruciating and intense than that of Don Quixote. The latter is belaboured by rough shepherds and by convicts whom he himself has set free. Hamlet’s wounds, on the other hand, are self-inflicted; the blade with which he vexes and torments himself is the double-edged sword of analysis.

- Nikolai Leskov, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1865)

Trans. Alfred Edward Chamot (1923)

In our part of the country you sometimes meet people of whom, even many years after you have seen them, you are unable to think without a certain inward shudder. Such a character was the merchant’s wife, Katerina Lvovna Izmaylova, who played the chief part in a terrible tragedy some time ago, and of whom the nobles of our district, adopting the light nickname somebody had given her, never spoke otherwise than as the Lady Macbeth of the Mzinsk District.

- Ivan Turgenev, ‘King Lear of the Steppe’ (1870)

Trans. Constance Garnett, London: William Heinemann (1906)

We were a party of six, gathered together one winter evening at the house of an old college friend. The conversation turned on Shakespeare, on his types, and how profoundly and truly they were taken from the very heart of humanity. We admired particularly their truth to life, their actuality. Each of us spoke of the Hamlets, the Othellos, the Falstaffs, even the Richard the Thirds and Macbeths—the two last only potentially, it is true, resembling their prototypes—whom he had happened to come across.

‘And I, gentlemen,’ cried our host, a man well past middle age, ‘used to know a King Lear!’

‘How was that?’ we questioned him.

‘Oh, would you like me to tell you about him?’

‘Please do.’

And our friend promptly began his narrative.’

- Lev Tolstoy, ‘On Shakespeare and on Drama’ (1906)

Tolstoy on Shakespeare: a Critical Essay on Shakespeare, trans. V. Tchertkoff and I.F.M.

(1906)

I remember the astonishment I felt when I first read Shakespeare. I expected to receive a powerful esthetic pleasure, but having read, one after the other, works regarded as his best: King Lear, Romeo and Juliet,Hamletand Macbeth, not only did I feel no delight, but I felt an irresistible repulsion and tedium, and doubted as to whether I was senseless in feeling works regarded as the summit of perfection by the whole of the civilized world to be trivial and positively bad, or whether the significance which this civilized world attributes to the works of Shakespeare was itself senseless. […] For a long time I could not believe in myself, and during fifty years, in order to test myself, I several times recommenced reading Shakespeare in every possible form, in Russian, in English, in German and in Schlegel’s translation, as I was advised. Several times I read the dramas and the comedies and historical plays, and I invariably underwent the same feelings: repulsion, weariness, and bewilderment. At the present time, before writing this preface, being desirous once more to test myself,

I have, as an old man of seventy-five, again read the whole of Shakespeare, including the historical plays, the Henrys, Troilus and Cressida, TheTempest,Cymbeline, and I have felt, with even greater force, the same feelings, – this time, however, not of bewilderment, but of firm, indubitable conviction that the unquestionable glory of a great genius which Shakespeare enjoys, and which compels writers of our time to imitate him and readers and spectators to discover in him non-existent merits, – thereby distorting their esthetic and ethical understanding, – is a great evil, as is every untruth.’

Although I know that the majority of people so firmly believe in the greatness of Shakespeare that in reading this judgment of mine they will not admit even the possibility of its justice, and will not give it the slightest attention, nevertheless I will endeavor, as well as I can, to show why I believe that Shakespeare can not be recognized either as a great genius, or even as an average author.

For illustration of my purpose I will take one of Shakespeare’s most extolled dramas, King Lear, in the enthusiastic praise of which, the majority of critics agree.

‘The tragedy of Lear is deservedly celebrated among the dramas of Shakespeare,’ says Dr. Johnson. ‘There is perhaps no play which keeps the attention so strongly fixed, which so much agitates our passions, and interests our curiosity.’

‘We wish that we could pass this play over and say nothing about it,’ says Hazlitt, ‘all that we can say must fall far short of the subject, or even of what we ourselves conceive of it. To attempt to give a description of the play itself, or of its effects upon the mind, is mere impertinence; yet we must say something. It is, then, the best of Shakespeare’s plays, for it is the one in which he was the most in earnest.’

‘If the originality of invention did not so much stamp almost every play of Shakespeare,’ says Hallam, ‘that to name one as the most original seems a disparagement to others, we might say that this great prerogative of genius, was exercised above all in Lear. It diverges more from the model of regular tragedy than Macbeth, or Othello, and even more than Hamlet, but the fable is better constructed than in the last of these and it displays full as much of the almost superhuman inspiration of the poet as the other two.’

‘King Learmay be recognized as the perfect model of the dramatic art of the whole world,’ says Shelley.

‘I am not minded to say much of Shakespeare’s Arthur,’ says Swinburne. ‘There are one or two figures in the world of his work of which there are no words that would be fit or good to say. Another of these is Cordelia. The place they have in our lives and thoughts is not one for talk. The niche set apart for them to inhabit in our secret hearts is not penetrable by the lights and noises of common day. There are chapels in the cathedrals of man’s highest art, as in that of his inmost life, not made to be set open to the eyes and feet of the world. Love, and Death, and Memory, keep charge for us in silence of some beloved names. It is the crowning glory of genius, the final miracle and transcendent gift of poetry, that it can add to the number of these and engrave on the very heart of our remembrance fresh names and memories of its own creation.’

‘Lear is the occasion for Cordelia,’ says Victor Hugo. ‘Maternity of the daughter toward the father; profound subject; maternity venerable among all other maternities, so admirably rendered by the legend of that Roman girl, who, in the depths of a prison, nurses her old father. The young breast near the white beard! There is not a spectacle more holy. This filial breast is Cordelia. Once this figure dreamed of and found, Shakespeare created his drama…. Shakespeare, carrying Cordelia in his thoughts, created that tragedy like a god who, having an aurora to put forward, makes a world expressly for it.’

‘In King Lear, Shakespeare’s vision sounded the abyss of horror to its very depths, and his spirit showed neither fear, nor giddiness, nor faintness, at the sight,’ says Brandes. ‘On the threshold of this work, a feeling of awe comes over one, as on the threshold of the Sistine Chapel, with its ceiling of frescoes by Michael Angelo, – only that the suffering here is far more intense, the wail wilder, and the harmonies of beauty more definitely shattered by the discords of despair.’

Such are the judgments of the critics about this drama, and therefore I believe I am not wrong in selecting it as a type of Shakespeare’s best. […]

Not to mention the pompous, characterless language of King Lear, the same in which all Shakespeare’s Kings speak, the reader, or spectator, can not conceive that a King, however old and stupid he may be, could believe the words of the vicious daughters, with whom he had passed his whole life, and not believe his favourite daughter, but curse and banish her; and therefore the spectator, or reader, can not share the feelings of the persons participating in this unnatural scene.

[…]

Such is this celebrated drama. However absurd it may appear in my rendering (which I have endeavored to make as impartial as possible), I may confidently say that in the original it is yet more absurd. For any man of our time – if he were not under the hypnotic suggestion that this drama is the height of perfection – it would be enough to read it to its end (were he to have sufficient patience for this) to be convinced that far from being the height of perfection, it is a very bad, carelessly composed production, which, if it could have been of interest to a certain public at a certain time, can not evoke among us anything but aversion and weariness. Every reader of our time, who is free from the influence of suggestion, will also receive exactly the same impression from all the other extolled dramas of Shakespeare, not to mention the senseless, dramatized tales, Pericles, Twelfth Night, The Tempest,Cymbeline, Troilus and Cressida.

But such free-minded individuals, not inoculated with Shakespeare-worship, are no longer to be found in our Christian society. Every man of our society and time, from the first period of his conscious life, has been inoculated with the idea that Shakespeare is a genius, a poet, and a dramatist, and that all his writings are the height of perfection. Yet, however hopeless it may seem, I will endeavour to demonstrate in the selected drama – King Lear– all those faults equally characteristic also of all the other tragedies and comedies of Shakespeare, on account of which he not only is not representing a model of dramatic art, but does not satisfy the most elementary demands of art recognized by all.

- Lev Tolstoy, The Light Shines in the Darkness (1902)

Trans. by Louise and Aylmer Maude (1928)

NICHOLAS IVÁNOVICH. I was going back to my room without having told you what I feel. [To Tónya] If what I say should offend you—who are our guest—forgive me, but I cannot help saying it. You, Lisa, say that Tónya plays well. All you here, seven or eight healthy young men and women, have slept till ten o’clock, have eaten and drunk and are still eating; and you play and discuss music: while there, where I have just been, they were all up at three in the morning, and those who pastured the horses at night have not slept at all; and old and young, the sick and the weak, children and nursing-mothers and pregnant women are working to the utmost limits of their strength, so that we here may consume the fruits of their labour. Nor is that all. At this very moment, one of them, the only breadwinner of a family, is being dragged to prison because he has cut down one of a hundred thousand pine-trees that grow in the forest that is called mine. And we here, washed and clothed, having left the slops in our bedrooms to be cleaned up by slaves, eat and drink and discuss Schumann and Chopin and which of them moves us most or best cures our ennui? That is what I was thinking when I passed you, so I have spoken. Consider, is it possible to go on living in this way? [Stands greatly agitated].

LISA. True, quite true!

LYÚBA. If one lets oneself think about it, one can’t live.

STYÓPA. Why? I don’t see why the fact that people are poor should prevent one talking about Schumann. The one does not exclude the other. If one …

NICHOLAS IVÁNOVICH [angrily] If one has no heart, if one is made of wood …

STYÓPA. Well, I’ll hold my tongue.

TÓNYA. It is a terrible problem; it is the problem of our day; and we should not be afraid of it, but look it straight in the face, in order to solve it.

NICHOLAS IVÁNOVICH. We cannot wait for the problem to be solved by public measures. Every one of us must die—if not to-day, then to-morrow. How can I live without suffering from this internal discord?

BORÍS. Of course there is only one way; that is, not to take part in it at all.

NICHOLAS IVÁNOVICH. Well, forgive me if I have hurt you. I could not help saying what I felt. [Exit].

STYÓPA. Not take part in it? But our whole life is bound up with it.

BORÍS. That is why he says that the first step is to possess no property; to change our whole way of life and live so as not to be served by others but to serve others.

TÓNYA. Well, I see you have quite gone over to Nicholas Ivánovich’s side.

BORÍS. Yes, I now understand it for the first time—after what I saw in the village.… You need only take off the spectacles through which we are accustomed to look at the life of the people, to realise at once the connection between their sufferings and our pleasures—that is enough!

MITROFÁN ERMÍLYCH. Yes, but the remedy does not consist in ruining one’s own life.

STYÓPA. It is surprising how Mitrofán Ermílych and I, though we usually stand poles asunder, come to the same conclusion: those are my very words, “not ruin one’s own life.”

BORÍS. Naturally! You both of you wish to lead a pleasant life, and therefore want life arranged so as to ensure that pleasant life for you. [To Styópa] You wish to maintain the present system, while Mitrofán Ermílych wants to establish a new one.