The following paper was delivered to the DH Lawrence Society in Eastwood on 14th October 2020.

The genesis of this talk is one tiny moment in a medium-length poem by Lawrence, ‘Baby Tortoise’.

This is a poem about something small – a baby tortoise on its first day. But even then, by line 56 in the poem we are still not quite expecting this:

‘No bigger than my thumb-nail’

Whatever our prior apprehensions about what size tortoises are at birth – and to be honest I never imagined them being so small, notwithstanding the problems of giving birth to a medium-sized tortoise – we have been given no clue by the poem.

The baby tortoise has not only been minified to a ‘small insect’ and an ‘atom’, but his mouth has been magnified to a ‘hawk-beak’ and an ‘iron door’; he is a ‘Ulysses’, a ‘Titan’ and his face is even a ‘little mountain front’.

In all this Gulliverian shifting of scale we are lost until we suddenly reach the objective yard-stick, or inch-stick in this case: ‘my thumb-nail’.

Suddenly we are back in the world that of consistent scale, where the baby tortoise is no bigger than a man’s thumb-nail, but is bigger than an atom, and the man attached to the thumbnail is smaller than the mountain.

It was at the very point of stumbling across this line and being struck by it as never before, a few months ago, that I was asked whether I would be prepared to speak to the Society in October, so I impulsively said ‘yes’ to the invitation, and, when asked what my topic was, said ‘scale’.

I then very much hoped that it would be the case that there was more going on with Lawrence and scale than this one baby tortoise, and so, I hope to persuade you, it has turned out.

A Lawrencian friend, curious about my topic, asked whether by choosing it I was saying that size matters. I said that difference of size matters, and that that is both true of actual physical size, and of size used as a metaphor, as we do in speech and thought all the time, Lawrence no less than any of us.

This is, in other words, a big topic, on which I’d like to zoom in and magnify some details, across a range of Lawrence’s works.

What I think is going on in ‘Baby Tortoise’ is that with the exception of the line ‘no bigger than my thumb nail’, the poet is relinquishing the world of consistent scale.

An earnest new born being, the baby tortoise making his way through the universe is a non-pareil. He and he alone carries ‘All life’ on his ‘shoulder, /Invincible fore-runner’ – and that is the sense in which he is a ‘Ulyssean atom’. After all, Ulysses, as much as he, was an atom on the infinite scale of the universe, so why then should not he be a Ulysses? There is no contradiction.

This makes me think of the essay ‘Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine’, where it is only ‘at the level of’ what Lawrence calls ‘existence’ that there is a consistent scale, physical and in terms of power. ‘There is competition’, and the man kills the porcupine because he kills trees, and the porcupine kills the tree because he lives from the bark, and the horse St Mawr in the novella of that name can kill a groom that annoys him, and Swift’s houhynhyms can chastise yahoos who annoy them, and Alice can scatter the entire attendance of the court room once she is full size because they are ‘nothing but a pack of cards’.

There is another dimension, which Lawrence numbers as the ‘fourth dimension’ and calls that of ‘being’, where ‘Any creature that attains to its own fulness of being, its own living self, becomes unique, a nonpareil’, and can, presumably, carry the universe on its shoulders too.

This quite apart from the fact that size isn’t everything even in the Hobbesian-Darwinian world of ‘existence’, because ‘The ant is more vividly alive than the pine-tree. We know it, there is no trying to refute it, and ‘the little ant will devour the life of the huge tree’, and the man can kill the elephant, or the mountain lion, just as the Lilliputians can bind Gulliver. And the mosquito can not only enrage the man, as we hear in the poem ‘Mosquito’, but kill him, as he nearly did when Lawrence had malaria in 1925; in this sense he not only stands on ‘high legs’ and is an ‘exaltation’ because of his internal scale – that is his massive height to leg width ration – but because he is, in his responsibility for millions of human deaths over the course of history, a ‘Winged Victory’.

There is even a sense in which relative smallness gives a metaphorical advantage, because it renders you closer to the fundamentals of life. The Baby Tortoise is a ‘bean’, ie all potential – and an ‘atom’, ie the unit of which all else is made.

Hence the trance into which Ursula Brangwen falls in The Rainbow when she sees a unicellular life-form through the microscope:

‘It was alive. She saw it move—she saw the bright mist of its ciliary activity, she saw the gleam of its nucleus, as it slid across the plane of light.’

She comes to understand ‘that it was not limited mechanical energy, nor mere purpose of self-preservation and self-assertion. It was a consummation, a being infinite. Self was a oneness with the infinite. To be oneself was a supreme, gleaming triumph of infinity.’

So it is the unicellular organism, the very tiniest, that guarantees the realm of existence as opposed to being – whatever Ursula’s evolutionist-materialist Professor cheekily named Dr Frankstone might say to the contrary.

Tellingly she is torn from this trance, where she stands in ‘an intensely-gleaming light of knowledge’ of ‘the new world’ by the need to go and meet Skrebensky, who has arrived to see her on the fateful visit when they will disastrously become lovers.

She doesn’t know it at the time, but she has been torn out of the realm of existence into that of being, and away from union with the fundamentals of life to union with a merely well-dressed man who will eventually all but threaten her life. She would have done better to stick to the small scale.

And so it is that in ‘Tortoise Family Connections’ the baby tortoise can be simultaneously the ‘Bud of the universe’ and the ‘Pediment of life’. When Lawrence asks ‘give us gods!’ in the poem of that name:

‘the father of all things swims in a mist of atoms

electrons and energies, quantums and relativities’

and it is the ‘wild swan’, not any larger animal, that represents procreation, and ultimate godliness; he has the right to the woman.

But that is in that poem – and all his poems, as he argues in the Preface to Pansies, and all achieved beings, according to Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine – are non-pareils.

In a poem such as ‘First Morning’ it is man, not swan, that belongs with woman. And indeed it is man and woman together – their love for each other – that holds the universe in place: that too is a fundament.

After an unsuccessful night of sex, the poet and his love, aka Lawrence and Frieda, sit outside in the South Bavarian sunshine looking one moment at the large scale, ‘the mountain-walls’, and the next at the small scale:

‘so near at our feet in the meadow

Myriads of dandelion pappus

Bubbles ravelled in the dark green grass

Held still beneath the sunshine–‘

The last stanza runs:

‘It is enough, you are near –

The mountains are balanced,

The dandelion seeds stay half-submerged in the grass;

You and I together

We hold them proud and blithe

On our love.

They stand upright on our love,

Everything starts from us,

We are the source.’

In this case the lovers’ love supports both the mountains and the dandelion seeds; mountains and seeds are both, on their different scales, ‘proud and blithe’ therefore mutually incomparable, and the lovers’ love is the guarantor and ‘source’ of both.

But, to backtrack a moment to the swan and the woman – a partnering we see also in Lawrence’s poem ‘Leda’ – one of the points here is that Lawrence is oblivious to the size discrepancy between them.

Similarly, in the short story ‘You Touched Me’, it is mentioned that Matilda is ‘tall’ and that Hadrian is ‘small’, but the narrator is tactfully restrained about their relative heights, even when they are in the same scene. In the last scene it is observed that she ‘stooped’ to kiss her father, but merely that she ‘put forward her mouth’ when commanded to kiss her new husband, even though this would also mean a stooping; as though such an observation would be irrelevant to the seriousness of this final moment.

But differences of scale between sexual partners are not always overlooked by Lawrence.

Perhaps his awareness of his own slightness relative to Frieda inflected his wry reflection in the poem ‘Lui et elle’ – presumably referring to the parents of our Baby Tortoise – where the poetic persona seems to be identifying with the male:

‘Mistress, reptile mistress,

You are almost too large, I am almost frightened.’

Then ‘I’ is replaced by ‘he’:

‘He is much smaller,

Dapper beside her,

And ridiculously small.’

Reverse the size difference by gender and Lawrence can also be discomfited by it, just as Ursula in Women in Love is appalled by the contrast between the ‘small, finely made’ girl and the ‘great naked horse’ on which she sits in Loerke’s sculpture, the horse according to Ursula representing Loerke himself, who, though small for a man, is big to a girl.

The girl being, quote, ‘young and tender, a mere bud’ does not make her, like the baby tortoise, the centre of the universe, nor yet full of potential; she is merely vulnerable, living on the plane of Lawrencian ‘existence’ (as opposed to being) only, and therefore vulnerable to the horse and to the artist who placed her there in his imagination, and beat her in his studio. She feels no such attraction to the, quote: ‘massive, magnificent stallion, rigid with pent-up power’ as Lou Witt in the novella St. Mawr feels for her stallion.

And it is therefore no surprise that the first question of Gudrun, who turns both ‘pale’ and ‘dark’ and supplicatory to Loerke on seeing the photograph of his sculpture, is ‘How big is it?’

We do not learn his answer. He gestures with his hands ‘so high’ without the pedestal, and ‘so’ with. These distances from the floor could be anywhere as far as the reader is concerned; size is occult information, vouchsafed nonverbally, through the actions of his body, only to Gudrun, who remains ‘cringing’ on receiving it.

Gerald, meanwhile, stoutly objects: ‘Why did you have such a young Godiva..? … She is so small … on the horse—not big enough for it’. It is Loerke who responds ‘I don’t like them any bigger’ – he immediately adds ‘any older’, but ‘any bigger’ comes first – whilst regarding men he is explicit that it is only size that counts: ‘A man should be big and powerful—whether he is old or young is of no account, so he has the size, something of massiveness’. His own failure to fulfil his desideratum – he is a ‘little man’ with a ‘boyish figure’ – cannot but help make one think about a similar contradiction in his Austrian-artist-contemporary, Adolf Hitler, who extolled the Aryan type without embodying it. This is the world of Darwinian being indeed, but there is no sexual selection here – only rape.

So to summarise where we’ve got to so far, and to return to my Lawrencian friend’s question: size both matters and doesn’t, depending on what dimension you’re in and whether you’re having sex or not.

So much for actual size.

But what about apparent size – that which depends on the proximity of the seeing eye?

We have already observed that Lawrence, and Ursula, have a sense of the fundamentals of life that is given to them by the most powerful magnifier humanity had and has yet invented – telescopes included – the microscope.

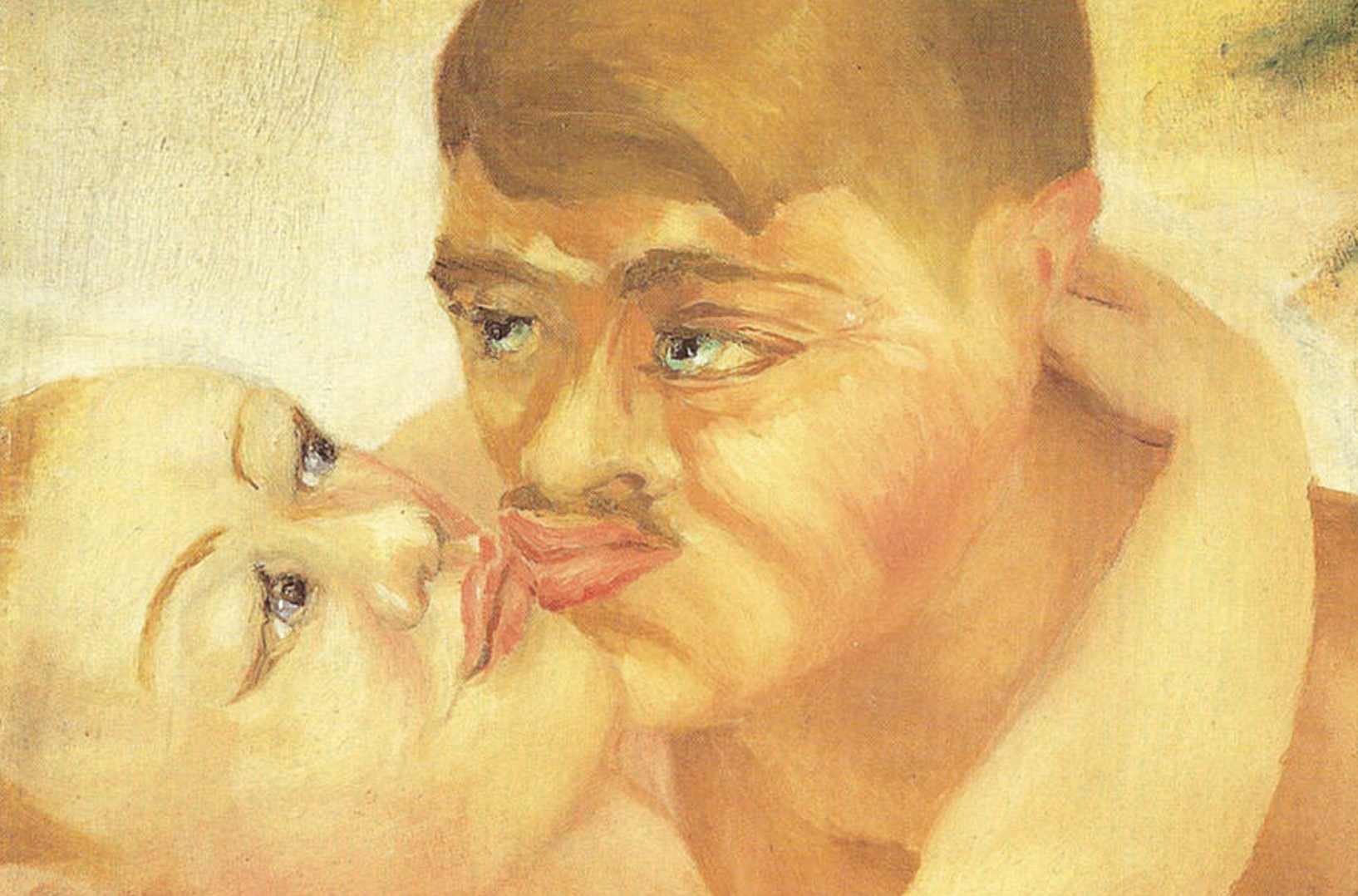

But a different kind of lens offers a different kind of close-up. In his essay ‘Pornography and Obscenity’ Lawrence writes: ‘The most obscene painting on a Greek vase is not as pornographical as the close-up kisses on the film, which excite men and women to secret and separate masturbation’.

Thus in the poem ‘When I went to the film’ the audience is, quote, ‘moaning from close-up kisses, black-and-white kisses that could not be felt – the close-up being the ultimate in the faked intimacy of the cinema, since in real life the ultra-close-up only happens between parents and children, or sexual partners

With regard to the painting ‘Close-up [Kiss]’, Keith Sagar argues that this turns the black-and-white kisses of Lawrence’s poem into colour, in a prophetic anticipation of the development of technicolor. He also observes that it could resemble the giant poster advertising the film A Woman’s Love being shown at Tevershall cinema, which Constance Chatterley catches sight of – colour having arrived in advertising posters several decades earlier than in film.

But if this is a painting of film actors on set – a still from a film imagined as filmed, or prophetically in technicolor – that poses the problem that actors in a 1928 film (the year of the painting) would certainly not be naked.

If this is a negative vision, then the objection could be raised that it is a vision hardly if any more distasteful than that of many other naked bodies in Lawrence’s paintings which Lawrence apparently considered attractive.

But what we can safely say is that we are not, in the essay or the poem or the painting, in Brobdingnag, where Gulliver is physically disgusted to see human flesh close up:

‘I must confess no object ever disgusted me so much as the sight of her monstrous breast, which I cannot tell what to compare with, so as to give the curious reader an idea of its bulk, shape, and colour. It stood prominent six feet, and could not be less than sixteen in circumference. The nipple was about half the bigness of my head, and the hue both of that and the dug, so varied with spots, pimples, and freckles, that nothing could appear more nauseous.

On the contrary, Lawrence repeatedly jibes Swift for such revulsion from the body experienced close-up, from the knowledge that ‘Celia Celia Celia shits’ – a line from Swift’s poem ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ – so it follows that nowhere in Lawrence, as far as I am aware, do we get a disgusting close-up.

On the contrary, getting close up to things is the pre-requisite for seeing wonders. At what must have been extremely close proximity to the baby-tortoise he can see details such as an ‘impervious mouth.’ ‘Suddenly beak-shaped, and very wide, …. Soft red tongue, and hard thin gums/ Then close the wedge of your little mountain front’

To see the baby tortoise’s face as a ‘little mountain front’ is to see the world as fractal (in anticipation of the mid-1970s coinage), that is, with the same patterning on a section of any size as on one of any other size. A mountain front therefore resembles the face of a baby tortoise just as much as the reverse is true.

There is a very different, but also sympathetic and analogising, close-up in the poem ‘Embankment at Night, before the War: Outcasts’.

The distance of the narrating ‘I’ is roughly that of someone passing by observing the homeless sleeping under Charing Cross bridge, until suddenly we are made to see:

| ‘The balls of five red toes | |

| As red and dirty, bare | 50 |

| Young birds forsaken and left in a nest of mud—’ |

The fact that the metaphoric augmentation is so slight, from the ball of a toe to a baby bird, has its own pathos. The abandoned bird and the abandoned youth, both houseless in the mud, have so much importantly in common despite their mutual difference of size and power, because the youth exists on his own larger scale of human power, measured by which he is tiny.

It therefore inculcates the sense of relativity which comes from any sense of scale based on at least two points, and which is summed up in the phrase ‘it’s all relative’.

Alice in Wonderland – in a work that the young Lawrence liked a great deal – finds being ‘so many sizes in one day very confusing you know’, but it also teaches her the relativity of size. At the end of the trial scene, grown to her own full child size, she realises that the tribe of hearts are only a pack of cards, but then wakes up next to her own bigger sister, who hears her story, and then, in a reverie, imagines Alice bigger still – the woman that she will be in the future, having eaten on the right side of the mushroom of time.

It is a benign version of the scale shift that takes place at the end of Lord of the Flies, when the terrifying and torturing dictator Jack runs out onto the island’s beach to find adult sailors, in whose eyes he is ‘A little boy who wore the remains of an extraordinary black cap on his red hair and who carried the remains of a pair of spectacles at his waist’. But the gigantic sailor himself is just a pawn – to use an Alice through the Looking Glass metaphor – in the giant world war that is currently raging, and which has brought him to this island. Likewise, his degree of ‘civilisation’, in comparison to the degenerated boys, is only relative.

In his 1926 essay ‘Man is a Hunter’, Lawrence senses pathos in the idea of eating of specifically small birds: ‘three robins, two finches, four hedge sparrows, and two starlings’ ‘‘imagine the small mouthful of little bones each of these tiny carcasses must make!’

But his comparative mind runs on: ‘after all, a partridge and a pheasant are only a bit bigger than a sparrow and a finch. And compared to a flea, a robin is big game. It is all a question of dimensions.’

Gulliver, if he is to be believed, inhabits a world in which there are beings, the Lilliputians, who are smaller than him – and other beings, the Brobdingnagians, who are larger than him, and upon discovering them his understanding of humanity is further relativized within the scale of existence.

This learning of relativity has great moral functions.

Gulliver’s sense of what is possible in a society is expanded by his encounters with both larger and smaller beings than Englishmen.

Like Gulliver, Lawrence restlessly travelled the world, leaving England in haste again every time he returned to it, and along the way finding many standards of comparison that made him even more critical of the English – and, just occasionally, less so.

He would certainly have been aware of the parallel; his novel The Boy in the Bush likens Australians to Yahoos; the vision of ‘St Mawr’ is arguably in equal parts distrustful of humanity and admiring of horses, as Gulliver admires the Houhynyms.

But through travelling Lawrence also gains a sense of the physical scale of the world. When Mr Noon, standing in the valley of the Isar on a bright spring morning, becomes unEnglished, he comes to see England as ‘so tight, little’ in contrast to the ‘vastness’ of the European continent, and he has the sense that he could just keep walking, to Italy (as he and Lawrence did) or to Russia (as they didn’t).

Anna Brangwen experiences a cosmic version of double scale extension at Lincoln Cathedral. Will’s soul is ‘absorbed by the height’ of the nave, which puts humanity in perspective – but Anna is angered by this, and she reflects:

‘After all, there was the sky outside, and in here, in this mysterious half-night, when his soul leapt with the pillars upwards, it was not to the stars and the crystalline dark space, but to meet and clasp with the answering impulse of leaping stone’

She then even scales up the sky, by positioning it relationship to the universe rather than to the earth: ‘she remembered that the open sky was no blue vault [a deliberately architectural term], no dark dome hung with many twinkling lamps, but a space where stars were wheeling in freedom, with freedom above them always higher.’

And in order to smash what she sees as the false absolutism of the Cathedral in relation to infinite space, she goes to the opposite end of the scale:

‘she caught at little things, which saved her from being swept forward’

‘she caught sight of the wicked, odd little faces carved in stone’

‘They winked and leered, giving suggestion of the many things that had been left out of the great concept of the church. “However much there is inside here, there’s a good deal they haven’t got in,” the little faces mocked.’

A Study of Thomas Hardy has a similar critique of a moral scale which presents itself as ultimate but which is not, beyond it lying the whole unbounded universe:

‘The vast, unexplored morality of life itself, what we call the immorality of nature, surrounds us in its eternal incomprehensibility, and in its midst goes on the little human morality play, with its queer frame of morality … till some one of the protagonists chance to look out of the charmed circle, weary of the stage, to look into the wilderness raging around. Then he is lost, his little drama falls to pieces, or becomes mere repetition, but the stupendous theatre outside goes on’

And as you will know, he praises Hardy, Shakespeare, Sophocles and Tolstoi for quote ‘setting a smallersystem of morality, the one grasped and formulated by the human consciousness within the vast, uncomprehended and incomprehensible morality of nature or of life itself’, whilst criticising Tolstoy and Hardy’s tragedies for operating on the smaller scale:

‘Like Clym, the map appears to us more real than the land. Short sighted almost to blindness, we [pore] over the chart, map out journeys and confirm them: and we cannot see life itself giving us the lie the whole time.’

Lawrence revisits this idea in satirical mode in the poem ‘Ships in Bottles’, where the bottles are metaphors not for social morality, but for the limited parameters – when measured against life – of intellectual debate:

‘Ah, in that parlour of the London pub

What dangers, ah, what dangers!

Caught between great icebergs of doubt

They are all but crushed

Little ships.

Nipped upon the frozen floods of philosophic despair

High and dry.

Reeling in the black end of all beliefs

They sink.

Yet there they are, there they are,

Little ships

Safe inside their bottles!

…

[and the last line]:

The storm is words, the bottles never break.’

But if the journey here is to an intellectual Lilliput, Lawrence makes another kind of journey to a physical prehistoric Brobdingnag, with Darwin’s Beagle as his ship, in his poem ‘Humming-bird’, where he imagines that:

‘Humming-birds raced down the avenues.

…

And went whizzing through the slow, vast, succulent stems.

…

Probably he was big

As mosses, and little lizards, they say, were once big.

Probably he was a jabbing, terrifying monster.

We look at him through the wrong end of the telescope of time,

Luckily for us.’

All these last examples – from Mr Noon, The Rainbow, and ‘Humming-bird’ on the physical scale, and Study of Thomas Hardy and ‘Ships in Bottles’ on a metaphoric scale – suggest that size has its virtues. Whereas I have spent most of this talk suggesting that littleness is just dandy, and just as big and absolute as anything else, and maybe more so.

This brings us onto the question of size as metaphor. It is striking that the Swift uses size entirely positively. The Brobdignagians have a thing or two to teach the English, whereas the English have a thing or two to teach the Lilliputians.

The houyhnhyms are bigger and better than the yahoos.

To scale something down in one’s imagination, Swift’s example suggests, is to denigrate it. The novella ‘The Captain’s Doll’ rotates around the heroine Hannele’s minification of her lover to a perfect doll effigy, which she is first seen dressing, like a child.

She then chooses to exhibit it/him, to arrange him, quote ‘with his back against a little Japanese lacquer cabinet, with a few old pots on his right hand and a tiresome brass ink-tray on his left’. She then has him diminished still further into a painting of the doll as part of a still life alongside sunflowers and egg on toast – and in the end she sells him.

When Hepburn’s wife sees the doll, despite herself quote ‘looking extraordinarily like one of Hannele’s dolls’ and making Hannele herself look ‘almost huge’, she quote ‘held the puppet fast, her small, white fingers with their heavy jewelled rings clasped round his waist.’ Then she tries to buy it. The women haggle over the price, like a reversal of a slave auction where only men would haggle over the price of slave women.

Hannele’s friend Mitchka calls this behaviour ‘wirklich bös’, really wicked. And Hepburn himself is not best pleased. At first he seems to object simply to the metaphoric implications of his diminishment, especially given the apparent perfection of her depiction – that is, its capturing of him. According to him, it is wanting in respect on her part to hawk such a portrait of him round the shops of war-ravaged Germany.

‘Why shouldn’t I make a doll of you? Does it do you any harm?’

…

‘Yes, it does. It does me the greatest possible damage,’

But after they have had their sharp difference over Hannele’s mountain ecstasy, he states that his diminishment, rather than having metaphoric implications, is in fact metaphoric indicative of what women typically do to men when they love them.

So he delivers himself thus:

The most loving and adoring woman today could any minute start and make a doll of her husband – as you made of me …

And the doll would be her hero: and her hero would be no more than her doll. My wife might have done it. She did do it, in her mind. She had her doll of me right enough. Why, I heard her talk about me to other women. And her doll was a great deal sillier than the one you made. But it’s all the same. If a woman loves you, she’ll make a doll out of you. She’ll never be satisfied till she’s made your doll. And when she’s got your doll, that’s all she wants. And that’s what love means.

When Hannele finally asks to burn the painted representation of the doll that represents her love, it is a sign that she may be about to accept him as a man.

We get a similar phenomenon with reversed gender relations when Will Brangwen carves Adam and Eve, with Eve much the smaller, and experiences great sensual pleasure in thus creating his miniature Pygmalion. Quote:

With trembling passion, fine as a breath of air, he sent the chisel over her belly, her hard, unripe, small belly… He trembled with passion, at last able to create the new, sharp body of his Eve.

As Jane Costin notes in her chapter on sculpture in the Edinburgh Companion to DH Lawrence and the Arts, Anna objects that Will has made his Adam, quote ‘as big as God’, but Eve ‘so small’ and ‘like a little marionette’. Jane points out that this discrepancy in scale echoes that in Lawrence’s friend the artist Mark Gertler’s painting The Creation of Eve, where an Eve no bigger than a whippet is shown being taken out of the rib of Adam, as described in Genesis 2.22.

But as Shirley Bricout argues in her chapter on Biblical Aesthetics in the same volume, Anna is in fact arguing in consistency with Genesis 1.27, where there is no discrepancy of scale or precedence between man and woman: ‘So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them’.

Still, relatively speaking, Will’s Adam and Eve are both little.

Just as Loerke and Gudrun at the end of Women in Love quote ‘played with the past, and with the great figures of the past, a sort of little game of chess, or marionettes, all to please themselves. They had all the great men for their marionettes, and they two were the God of the show, working it all.’

These examples suggest that Lawrence disapproved of miniaturising. But he himself, eight years after finishing The Rainbow and four years after finishing Women in Love, participated in what Jane Costin describes as ‘a group effort to depict the Garden of Eden in plasticine’, where his own contributions were ‘a very red Adam’ and a ‘plump little Eve’.

Jane Costin argues that Lawrence admired the animal miniatures of the sculptor Gaudier-Brzeska, and the month before he died he asked for some clay to make his own ‘little animals’.

In Women in Love Gudrun specialises in miniatures. Ursula asks Hermione:

“Isn’t it queer that she always likes little things?—she must always work small things, that one can put between one’s hands, birds and tiny animals. She likes to look through the wrong end of the opera glasses, and see the world that way—why is it, do you think?”

Hermione suggests that:

‘The little things seem to be more subtle to her—’

“But they aren’t, are they? A mouse isn’t any more subtle than a lion, is it?”

There is actually some ambiguity in this conversation as to whether Gudrun sculpts small things at scale, or whether she minimises. It is noted that she sculpts water-wagtails, for example, but such a bird would not fit within one’s hands. Nor would a human being, and Birkin later tells Gerald that Gudrun sometimes sculpts ‘odd small people in everyday dress’. So she too creates dolls, men and women alike.

The discussion about subtlety ends with Ursula crossly announcing ‘I hate subtleties’, but she has already made the point that subtlety does not depend on scale, and this is consistent with much of what we have seen of Lawrence’s apprehension.

Hermione moves swiftly on to question of whether children’s souls are damaged by being roused to consciousness of small-scale realities such as the little red ovary flowers of the hazel putting out for pollen from the catkin, which Birkin had pointed out to Ursula by getting up close to her and the flowers. The close-up perspective, here, again, is vindicated.

Overall it is uncertain overall whether Gudrun’s gift at small-scale sculpting is one of her redeeming features, or whether it is too neatly the opposite and therefore counterpart of Loerke, who creates giant freezes. I think on balance it is the former. Which would indicate that not all minification is puppeteering and therefore to be condemned.

What, however, about the opposite – artistic augmentation?

Lawrence does this frequently too, as for example in the ‘Dolor of autumn’

By the end of the poem the poet stands:

‘exposed

Here on the bush of the globe,

A newly-naked berry of flesh

For the stars to probe.’

Here the earth is a bush, and man a berry upon it.

This reminds me of the Ted Hughes poem ‘February 17th’. Hughes, on his Devon farm of Moortown, finds a lamb that has died after only his head has emerged from his mother, and the rest could not follow, therefore he was strangled.

Hughes fetches a razor and then:

‘brought the head off

To stare at its mother, its pipes sitting in the mud

With all earth for a body.’

Here too, the vastly greater size of the earth compared to that of the individual mammal aggrandizes rather than shrinks the latter. And in Lawrence’s poem, the scale then shifts outwards further still, as the stars probe the man-cum-berry from much further away from the earth than the earth is larger than the man.

In the painting ‘Flight back into paradise’, Eve is enormous compared to the factories which she is dragging behind her and trying to escape. She has the heroic scale, as the mother of all humanity, and is on the same scale as Adam – Lawrence with a balloon-like chest – and the angel Michael; she is on the same scale as heaven (though on the actual painting, which is 145 by 97.5 cm, the figures are of course smallerthan life-size.)

We cannot see Adam’s bottom half, but if we could, he would most certainly possess a penis, whereas it is quite likely that the Captain’s doll has none at all, it having been shrunk infinitely more even than the rest of him.

By contrast in many of Lawrence’s descriptions of the phallus we get magnifying metaphors.

In the poem ‘Virgin Youth’:

‘He stands like a lighthouse’

A ‘column of fire’

And a ‘tower’

According to Tommy Dukes in Lady Chatterley’s Love, the phallus is the ‘bridge across the chasm’. Or according to Mellors, he is John Thomas – that is, man-sized.

But of course the phallus is the ultimate Alice in Wonderland, one moment big, the next moment small, and Alice says ‘being so many different sizes in a day is very confusing” – far more so than for the woman who (in pregnancy) swells so much more slowly, and diminishes, albeit faster, nowhere near as fast as the penis.

Like Alice, it can be big at inconvenient moments, and sometimes too big to get where it wants to be. And sometimes it is small and helpless, a little wowser, when it would be helpful to be big.

But in Lady Chatterley’s Lover Connie pays her respects to both scales:

‘Even when he’s soft and little I feel my heart

simply tied to him’

‘now she became aware of the small, bud-like reticence andtenderness of the penis, and a little cry of wonder and poignancyescaped her again, her woman’s heart crying out over the tender frailtyof that which had been the power.’

It is not just Connie.

Lawrence too had a clear tenderness for small things just because they were small. Think of The Baby Tortoise, and the toes of the rough sleeper. ‘Little’ is an adjective often used positively: After the Brangwen sisters have danced themselves dry at the Water-Party in Women in Love, they eat, quote,

‘delicious little sandwiches of cucumber’

And the deliciousness and the littleness are connected. Or consider the injunction, in his late great poem:

‘Oh build your ship of death, your little ark

and furnish it with food, with little cakes, and wine

A little ship, with oars and food

and little dishes … and little cooking pans

Containing a ‘little soul’

Making its way successfully, like the baby tortoise, forwards, on the great scale of immortality.

Or, at the opposite end of life’s temporal scale, think of the chicks in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Connie really starts getting interested in Mellors’s chicken coops when one day:

‘there was one tiny, tiny perky chicken

tinily prancing round in front of a coop’

… New life! So tiny and so utterly

without fear!’

It is after this point that

‘She had only one desire now, to go to the clearing in the wood.’

And on one occasion she finds three chicks’ whose ‘cheeky heads came poking sharply through the yellow Feathers [of the hen] then withdrawing, then only one beady little head eyeing forth from the vast mother-body.’

‘Little’ is repeated four times in the para before Mellors’s loins rise at the sight of Connie crouching over an ‘atom of balancing life’, and passing this atom back and forth is their closest contact to date and immediate prelude to beginning to create their own little atom of life.

Accordingly, big can sometimes be the reverse of better. Captain Hepburn is offended by the magnitude of the Austrian Alps, which he accuses of ‘affectation’ for their ‘uplift’. In a reversal of gender from the Lincoln Cathedral scene it is the woman who has ecstasies over something very large, leaving the man behind to puncture it:

‘You must be a little mad,’ she said superbly, ‘to talk like that about the mountains. They are so much bigger than you.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘No! They are not.’

‘What!’ she laughed aloud. ‘The mountains are not bigger than you? But you are extraordinary.’

‘They are not bigger than me,’ he cried. ‘Any more than you are bigger than me if you stand on a ladder. They are not bigger than me. They are less than me.’

‘Oh! Oh!’ she cried in wonder and ridicule.’ The mountains are less than you.’

‘Yes,’ he cried, ‘they are less.’

In Women in Love Birkin and Ursula both want to get down off the Alps in the end, to climb down off Mount Pisgah to the safer lowerlands, the little hills, as around Gargnano in Italy.

So how to conclude, after we have been so many sizes in one day?

Does size matter? In the realm of absolute existence, it does not, except that the tiniest and largest scales, the atom and the universe, point to the ultimate, within which all our human strivings are relativized.

It is good to feel this relativisation, and to feel the fractal nature of the universe, to look outside England and at the European continent, down at dandelion seeds and up at mountain fronts, down a microscope and up to the stars.

But within the relative world of being size does have some importance. It may determine survival. And even if does not always guarantee power or dignity, it metaphorically denotes them.

Yet the little has its own attraction, and it can be a metaphor not just for triviality or humiliation but for our innocence, vulnerability, and courage in the face of enormity. This applies as much to things seen close up as to those in themselves relatively small.

I will end with a quote from Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine:

‘The small are as perfect as the great, because each is itself and in its own place. But the great are none the less great, the small the small. And the joy of each is that it is so.’