Report of the Twentieth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

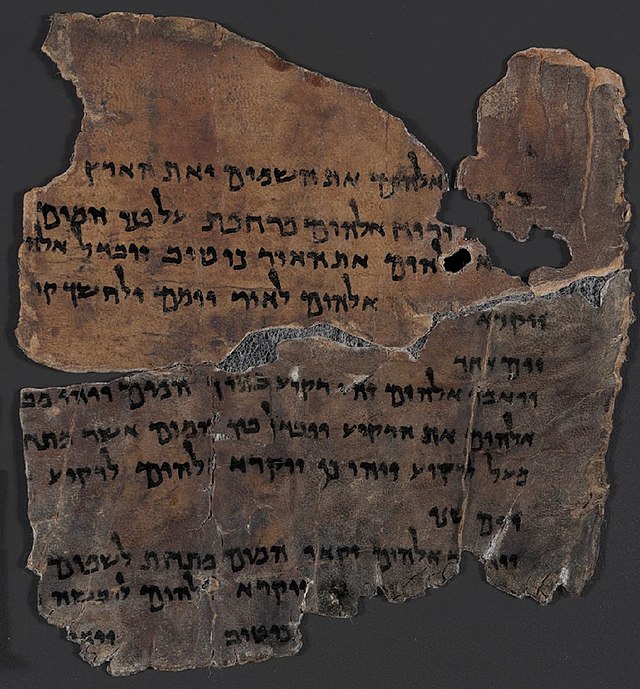

Shirley Bricout

D. H. Lawrence and the Patriarchs of the Book of Genesis

Thursday 24th March 2022

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

26 people attended, including, outside of England, the presenter Shirley Bricout, in Vannes, Britany, Tim Gupwell in Béziers, South France, Marina Ragachevskaya in Minsk, Shanee Stepakoff in Connecticut, Farasha Euker in Washington State, and Keith Cushman also in the States.

INTRODUCTION

Dr Shirley Bricout is affiliated to the University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 in France. She specializes in Lawrence and Biblical language, and is the author of Politics and the Bible in D. H. Lawrence’s “Leadership Novels” (Montpellier: Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2014). In this meeting she concentrated on the patriarchs of Genesis (with an incursion into Exodus), and considered how he gave (and denied) a voice to women in this patriarchal context.

The suggested readings were:

The first two pages of Apocalypse (pages 59-60 in the Cambridge edition)

The chapter ‘First Love’ in The Rainbow (in particular page 302 in the Cambridge edition)

Genesis chapter 6 and chapter 9: 8-25 in The King James Bible

THE PRESENTATION

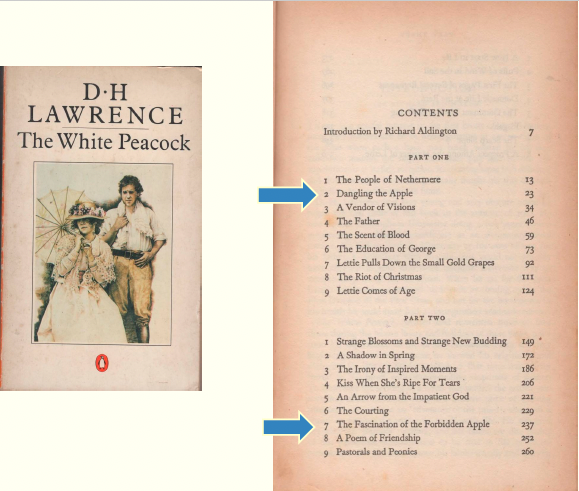

Shirley started by reminding us how much Lawrence wrote about the Bible; as Lawrence himself said: ‘The Bible was verbally trodden into the consciousness like innumerable foot-prints treading a surface hard” (Apocalypse 59), and Lawrence used Biblical imagery and language to articulate his own vision of the world from his boyhood on. She cited the titles Aaron’s Rod (1922), “Samson and Delilah” (1922), David (1926) Noah’s Flood (c. 1925), and chapter titles of The White Peacock (1911) : “Dangling the Apple” and “The Fascination of the Forbidden Apple”.

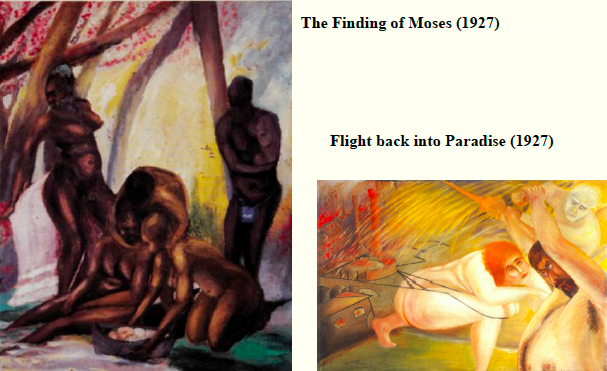

He made paintings entitled Finding of Moses and Flight Back into Paradise.

Shirley reminded us of Lawrence’s upbringing in the Congregationalist church to which his mother had converted, and which understood faith as a personal encounter with God facilitated by daily reading of the Bible. This upbringing was evidenced in the adduction of Biblical tropes and phrases in domestic songs and charades, such as that recalled by David Chambers: “He [Lawrence] played the part of Pharaoh, with the milksile on his head for crown, and hardened his heart ineluctably against the pleas of Moses and the children of Israel[1]”. Such a charade also occurs in Women in Love in the tableaux vivants based on Ruth (WL 91-2).

Shirley noted that Lawrence was mainly raised on the King James Version (1611), but that he also praised James Moffatt’s version of 1924, which divested the Bible of its Jacobeanism, and indicated typographically (in its New Testament) when the Old Testament was being quoted – an intertextual feature that he may well have found useful in writing Apocalypse.

She also noted the frequency with which Lawrence’s cadences are inflected by the language of the Bible. For example, in Kangaroo Somers’s curse on his inspectors: “because they had handled his private parts, and looked into them, their eyes should burst and their hands should wither and their hearts should rot”, resembles the parallelism of Zechariah 14.12: “Their eyes shall rot in their sockets, and their tongues shall rot within their mouths” (Moffatt).

Shirley then began her concentration on patriarchs – not on Adam and David, who have already been much discussed in Lawrence studies, but on Noah, Abraham, Lot and Jacob.

Jacob is the type of the patriarch in The Boy in the Bush, where Jacob Ellis is one of two brothers. His brother Esau has died, and his nephew is also called Esau. This Lawrencian Jacob, too, has many children, and Lennie is said to be the “Benjamin” (ie favourite son) of his father (BB 141).

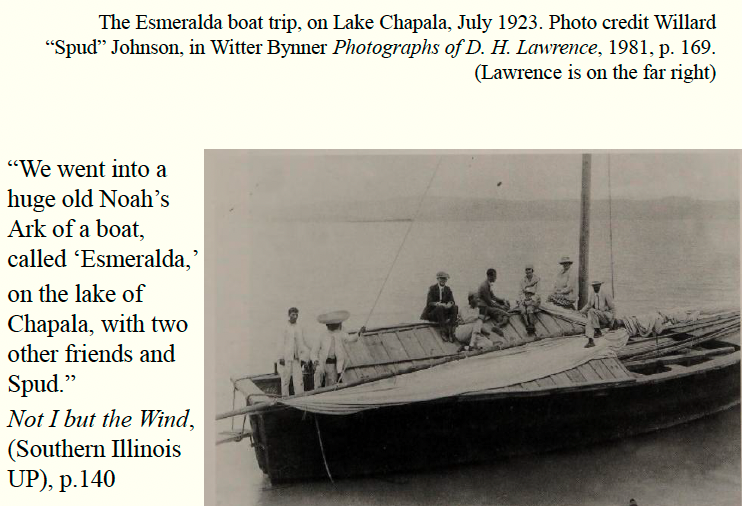

Noah was known even to young children, in part because of the nursery toys (such as arks and rainbows) associated with his child-friendly story. In Twilight in Italy Lawrence writes: “There were hundreds of cattle painted standing on meadows like a child’s noah’s-ark toys arranged in groups: a group of red cows, a group of brown horses, a group of brown goats, a few grey sheep.” (“A Chapel Among the Mountains” in Twilight and Italy and Other Essays, p. 33). Frieda mentions Noah’s ark in relation to an excursion that they made: “We went into a huge old Noah’s Ark of a boat, called ‘Esmeralda,’ on the lake of Chapala, with two other friends and Spud.” (Not I but the Wind, Southern Illinois UP, p. 140).

The Noah story formed an archetype, for Lawrence, between the old world and the new – the latter comprising the noblest survivors from the old world. Lawrence wrote about his Noah’s Flood play project in these terms: “in my idea they still belong to the old demi-god order – and their wives – faced with the world and the end of the world: and the jeering-jazzing sort of people of the world, and the sort of democracy of decadence in it: the contrast of the demi-gods adhering to a greater order: and the wives wavering between the two: and the ark gradually rising among the jeering” (3 March, 1925, Letters 5.217-18). He had already, a decade before, conceived of the apocalypse which he considered humanity to deserve in terms of a great flood: “It would be nice if the Lord sent another Flood and drowned the world. Probably I should want to be Noah. I am not sure.” (14 May, 1915, Letters 2.338-40).

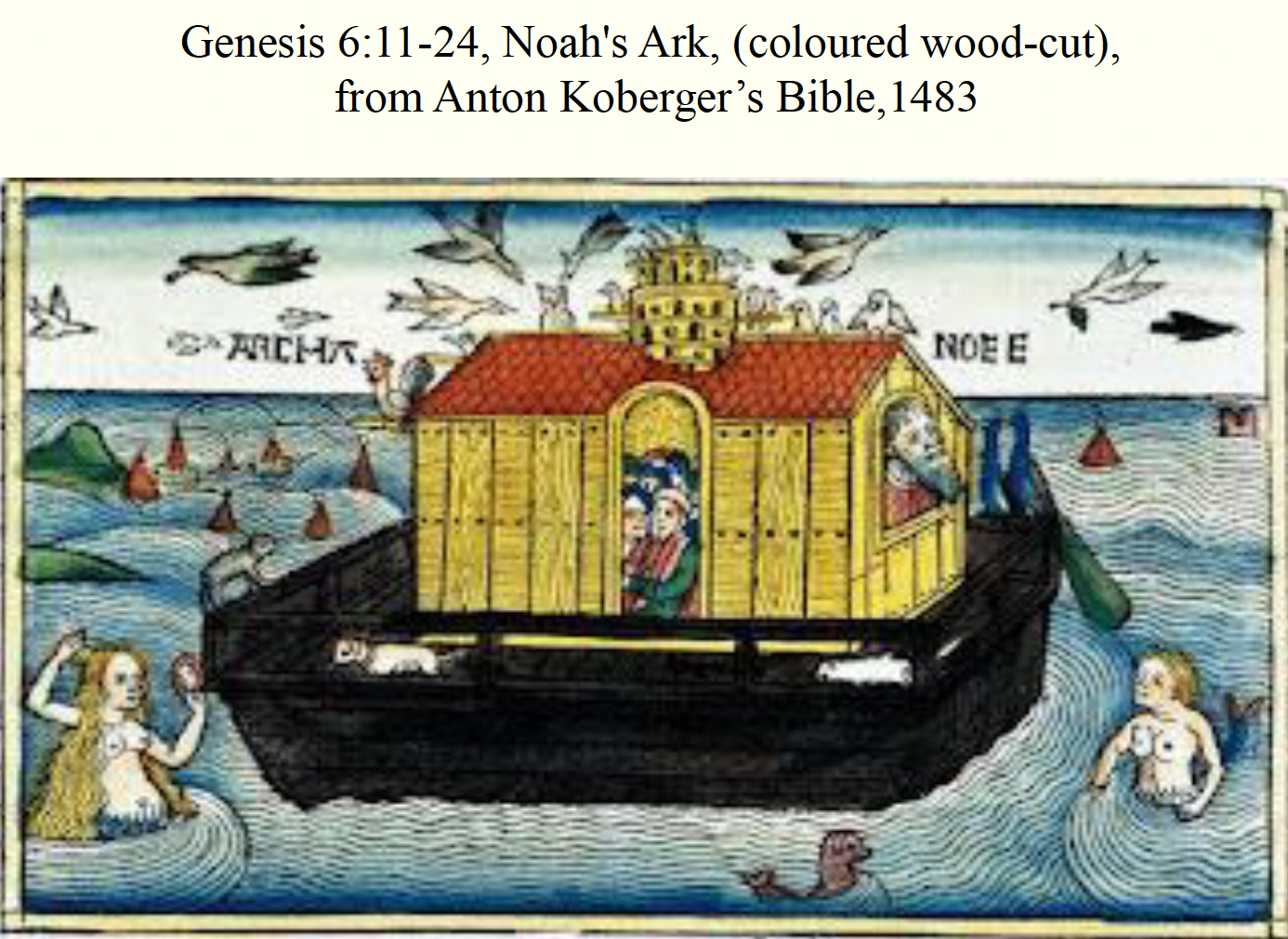

Yet in The Rainbow (Shirley cited Virginia Hyde as positing), Tom Brangwen can be thought of as “a latter-day Noah who drowns in the flood of modernism”. Thereafter a matriarchal era begins with “Anna Victrix” and continues in “First Love”, when Ursula reworks the story of the flood in feminist terms by imagining naiads who witnessed the flood and are amused at the four men in the ark thinking themselves masters of the post-flood universe. Shirley pointed out that Ursula’s vision resembles a fifteenth century Biblical illumination in which mermaids swim around the Ark.

Continuing this theme Shirley informed us that a Woman’s Bible was published in the year that Lawrence was born: Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s selection of Biblical verses with a feminist commentary. Lawrence’s next novel, Women in Love, had had as one potential title Noah’s Ark(3 Letters 183), the implication presumably being that Ursula and Birkin are held, together, above the floodline.

Turning to Abraham Shirley noted that in Kangaroo the eponymous character compares himself to Abraham carrying his people. He asks Somers: “And if I have to be a fat old Kangaroo with – not an Abraham’s bosom, but a pouch to carry young Australia in – why – do you really resent it ?” (K 120). Abraham is also the type of the patriarch in The Boy in the Bush, where Jack’s household, including flocks, employees, and the latter’s wives and children, resembles Abraham’s. He justifies his “legal marriage with Monica” and his “own marriage with Mary” on the grounds that:

The old heroes, the old fathers of red earth, like Abraham in the Bible, like David even, they took the wives they needed for their own completeness, without this nasty chop-and-change business of divorce. Then why should he not do the same?

Mollie Skinner queried this ending, which raises feminist questions, since Sarah submitted to Abraham.

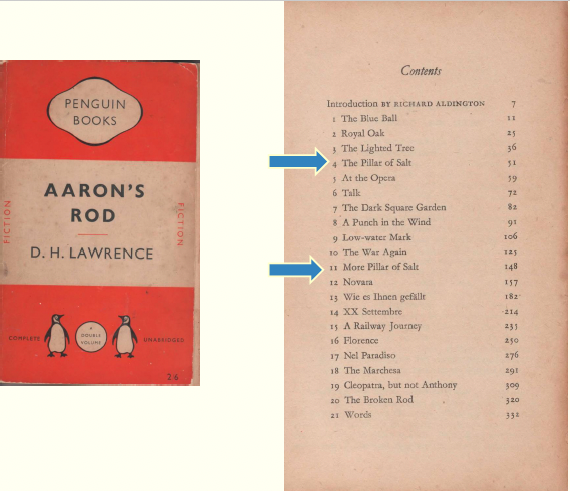

Finally Shirley turned to Lot, whose parting from Sodom, and his wife’s turning to a pillar of salt on turning to look back, is narrated in Genesis 19. Chapter titles in Aaron’s Rod include “The Pillar of Salt” and “More Pillar of Salt”.

Aaron’s wife being called “Lottie” – a feminine Lot – is therefore a Biblical joke, and in chapter 4 Aaron leaves her. Yet he twice comes back – once to watch his wife through a window (when he “stood motionless as if turned to a pillar of salt”, AR 44), and once to fetch his flute (when he is described as immobile whilst his wife cries, whereas it was the tears of Lot’s wife that turned her to salt, AR 125-26). The theme is treated again in Lawrence’s 1912 poem “She Looks Back”, which appeared in Look! We Have Come Through!. However, here the Lot’s wife character is Frieda turning back to her children, and the salt burns Lawrence.

Finally Shirley noted Lawrence’s scattered, subtle, references to Moses. For example Lawrence describes the Australian “fiery bush”, invoking Moses’ encounter with the burning bush. In “St Luke” in Birds, Beasts and Flowers (1920), Moses is presented with:

Horns

The golden horns of power,

Power to kill, power to create

Such as Moses had, and God,

Head-power.

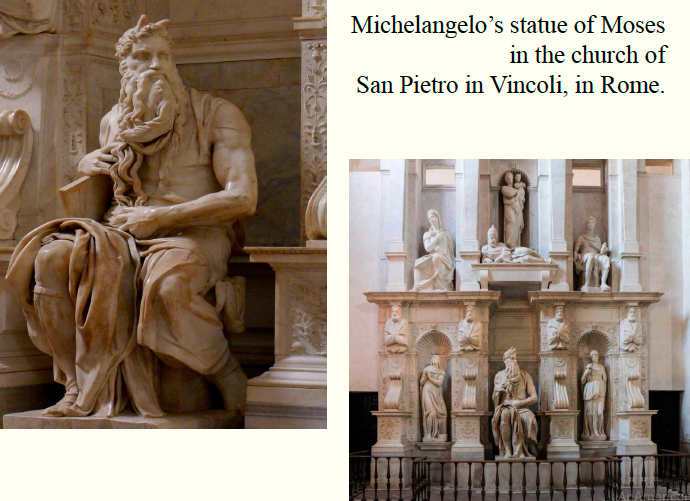

Indeed, Michelangelo’s statue of Moses in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, which Lawrence may have known, presents Moses with horns.

However, this was due to a mistranslation by St Jerome of a Hebrew word to “horned” instead of “radiant” – the radiance that Moses possessed after his encounter with God on Mount Sinai. Jerome’s was an honest mistake, whereas Lawrence’s reworkings of the Bible were creative misprision, used to express his own vision, to distinguish it from Biblical type, and to invoke intense emotion. These references require shared knowledge on the reader’s part, which many may no longer possess – but the editors of the Cambridge edition of Lawrence’s work helps readers supply the gaps. They also present issues to the translator of Lawrence into other languages, since it is impossible to retain Lawrence’s intertextuality with specific English translations of the Bible.

THE DISCUSSION

Picking up on the patriarchal vs. feminist theme of the talk, Nahla Torbay asked whether Lawrence could in general be considered to be patriarchal. Shirley replied that Lawrence’s inconsistency on this point, as on others, was reflected in his various treatment of Old Testament patriarchs, but in general, even when male voices dominate, a female voice can also be heard coming through. Moving away from the Bible, Sue Reid speculated that the nymphs in Ursula’s vision and the mermaids in the woodcut might also owe something to the Sirens in The Odyssey – a work beloved of the modernists and also evoked in The Rainbow.

Paul Filmer noted Lawrence’s metaphor of “saturation” when (in Apocalypse) describing his early contact with the Bible, and wondered whether Lawrence turned against the Bible in later works. Shirley responded that he retained it as a resource even whilst he questioned it, and that he could not have written as he did without having been saturated in the cadences of, especially, the King James Bible.

Catherine Brown asked whether Lawrence ever considered the Old Testament as specifically Jewish scripture. Shirley noted that Lawrence must have discussed the Hebrew Bible with his Jewish-Ukrainian friend Samuel Koteliansky, but that of these there is unfortunately no record. Catherine also asked whether Lawrence was ever as critical of any of the Old Testament patriarchs as he was of Christ. Michael Bell responded that David was the Old Testament focus of his criticism; Lawrence didn’t like the Florentine statue of him, nor having the name David himself, since he saw David as a Hamlet-figure tending towards Christ and the problems of modernity. Shirley agreed and noted that in Lawrence’s play David one feels this ambivalence. Whereas Samuel has an intimacy with God that is positive, when David arrives this intimacy is lost.

The meeting concluded with Michael Bell reaching out to Marina Ragachevskaya in Minsk à propos the Russian invasion of Ukraine which started one month before the meeting, on 24th February. Marina expressed her concerns about lack of political free speech in her own country and was not, at the time, sure that she would be granted the support of her university (the Minsk State Linguistic University) to travel to Paris for the University of Nanterre Lawrence conference in April. In the event, fortunately, she was.

[1]Nehls 47-48.