A Shade on the Sea Floor

An Interview with Jaya Savige about Derek Walcott (1930-2017) by Dr. Catherine Brown

Thursday 30th March 2017

Bedford Square Gardens, London

I met with my colleague Jaya Savige, Head of Creative Writing at new College of the Humanities, on the day that Derek Walcott died (17th March 2017). His reaction to this event, and my guess at Walcott’s importance to him as a poet, made me suggest that I interview him about the poet. What follows is an edited transcript of the interview that took place on a sunny afternoon in the key garden of Bedford Square, two weeks later.

Australian poet Jaya Savige, Head of Creative Writing at New College of the Humanities, London, and poetry editor of ‘The Australian’

Catherine Brown (CB): I actually saw you on the day that Derek Walcott died, that was the 17th of March and you were clearly moved by his death. How did it affect you?

Jaya Savige (JS): Yes, I’d just read the news of Walcott’s death when we saw each other at Trevor Nunn’s guest lecture [on directing Shakespeare], and you’re right, I was unusually moved, for one specific reason: I just so happened to have been obsessively reading and rereading a poem of his called The Gulf, on the train to and from work that week, and even earlier that day. I wasn’t aware he was close to passing, so when I saw the news on the BBC I was a little shocked by the fact that I’d just been reading him, had been reading him in his last days, and maybe even in his final moments. When I saw you I was still in the first stages of processing this coincidence.

I should mention that my response was really that of the poet in me more so than the scholar or academic. I was reading The Gulf because I was in the middle of drafting a poem myself, which is actually rare for me during the teaching year. In this mode, I’m always thinking about a line, about the next line, or about the shape of the poem I’m drafting, and I usually turn to one or two poems, for sustenance or guidance. The fact that I happened to turn to Walcott that week was a little unusual; I could just as easily have turned to any number of very different poets—I mean utterly different, like say John Ashbery [Note: Ashbery would pass away in September 2017] or Dean Young, W.S. Graham or Wallace Stevens, or any number of others. And of all poems, The Gulf—which is more about fissures and separation, rather than connection—was one that seemed especially haunting in the context of his passing.

CB: In what way? Could you tell us a little about the poem?

JS: The Gulf is a longish poem written from the perspective of a passenger on a flight over Texas and the Gulf of Mexico in the late 60’s, in the wake of the turbulence of that decade (the assassination of JFK is an important node in the poem). So the titular “Gulf” is not only the Gulf of Mexico, but also the gulf between north and south in the USA (i.e. the US Civil War, and so the gulf implicit in slavery also) and beyond that, the kind of gulf that can emerge between people (or peoples) more broadly; also the gulf between memory and experience; and even metaphysically, the gulf that separates the living and the dead.

CB: How did you first come into contact with Walcott’s work, and why does it resonate for you?

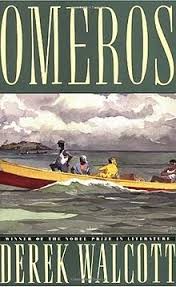

JS: Like everyone who studied English at university in Australia when I went through, I encountered A Far Cry From Africa in a Norton Anthology as an undergraduate; but I was almost exclusively drawn to North American and Australian poets in those days. It wasn’t until my late 20’s, when I was living in Rome on a writing residency for six months, that I began to read Walcott further. As I toured Italy giving readings, I met a poet in Turin who spoke so reverentially of Omeros that I thought I’d better take a look, so I did, and I found that I immediately recognised certain elements of the poem’s setting and subject matter.

Of course, I’m not from the Caribbean, and I have nothing in connection with its people or history; but I did grow up on an island (Bribie Island in Queensland, Australia, which has its own colonial history), barefoot on the beach from a young age. My first volume of poetry, Latecomers, is buffeted by the sea, salt and sand, and is concerned with layers of history (including the indigenous history of the island). So the humid, archipelagic landscape of Omeros, teeming with colonial ghosts, bears a striking resemblance to my home; that sound of the steady lapping of water is the soundtrack of my youth. The island I grew up on is subtropical rather than tropical (like the Caribbean), so the climate is slightly different, but I nevertheless identify with the setting and postcolonial context of Omeros on a more foundational level than I do, say, with the climate and landscapes of Britain and Europe.

Then there is the marvel of Walcott’s unique connection with the English language and with classical poetic traditions, as a writer who stood in many ways at an odd angle to them, and yet who made them his own and even extended their possibilities; and related to that, there is his virtuosic technical skill within those traditions. There’s the judgement and dextrousness on one hand, the intensity of the imagination on the other. And his diction is ravishing in the way of the tropics, a richness and diversity in abundance.

Of course Walcott’s was just one of a range of responses to the landscape and culture of the islands of the Caribbean, one way of expressing their dynamic relation to multiple historical colonial projects, and of dealing with all the challenges that go with being a writer in English in that context. Obviously each response is unique – you had Naipaul and CLR James, with their Trinidadian perspectives, the francophone Aimé Césaire and Édouard Glissant, and others like Jean Rhys, and perhaps most importantly in terms of poetry, Walcott’s contemporary, Edward Kamau Brathwaite; a whole variety of younger poets have followed in their wake. But Walcott was one of the 1930’s generation that is now passing, and very movingly too.

CB: Because they started it.

JS: Yes, they were pioneers in a sense, and there’s something moving about the passing of a pioneering generation of writers who opened up new vistas, new approaches. I mean it’s happening everywhere, the same generation is passing on here in England, in Australia too, though those cases have their own particulars.

Walcott’s approach of writing within, and to some extent repurposing the conventions of classical and European poetry was not without its critics or counter-urges. The poet Kwame Dawes has spoken of the great debate among young Jamaican writers in the 70s as to whether Walcott or Brathwaite was the greater poet; he likened it to choosing between Prince and Michael Jackson! I can understand why other Caribbean writers might prefer Brathwaite’s approach, which was to break from the inherited forms in favour of local forms and rhythms. That wasn’t my debate growing up, but I recognise it; I suspect every poet writing in English, but who isn’t English or British themselves, has to negotiate the issues involved in doing so and find their own path. It can be an existential concern, and there is something similar in my own experience as an Australian writer. Walcott’s approach is not exactly something I try to emulate, but I admire it, and he does it exquisitely well.

CB: Doesn’t Omeros kind of anticipate that kind of criticism by creating the character of Major Plunkett, who wants to project Homeric antiquity onto the islands? And he himself is engaging in some of the same projects as Walcott, but Walcott the poet has a distance from Plunkett too.

JS: I think that’s right. Plunkett is an interesting character; his wife, Maud, as well. (And he also has a relationship with Helen, their servant, whose beauty he finds alluring in an almost Orientalising kind of way.) But certainly yes, with Plunkett he seems to be working through those issues, and in a way that almost heads that criticism off at the pass…

CB: By not being so hard on him or so self-conflicted as to wholly reject him. There’s also an awful lot of sympathy for Plunkett.

JS: I think so. The Australian poet and novelist David Malouf once told me that if you create a character like that, sneering will kill him. It’s best to give them their humanity, where possible. Otherwise it won’t be successful; you’re not really there to judge, primarily, but to present (or even inhabit). This is of course Keats’s concept of negative capability, the ability to render contrary and conflicting states without yearning for resolution. And I think that Walcott is great at that; Plunkett is not just a whipping boy for the postcolonial critique. He’s more complex than that.

CB: Sure, sure.

JS: Just as the speaker of the poem is a complex figure. There’s a wonderful moment toward the end of Omeros (Chapter LIX) that addresses your point, where the poet questions the value of drawing parallels between the Greek Odyssey and his own landscape and people. He says [JS reads]:

Why waste lines on Achille, a shade on the sea floor?

Because strong as self-healing coral, a quiet culture

is branching from the white ribs of each ancestor,

deeper than it seems on the surface; slowly but sure,

it will change us with the fluent sculpture of Time,

it will grip like the polyp, soldered by the slime

of the sea-slug. Below him, a parodic architecture

re-erected the earth’s crusted columns, its porous

temples, stoas through which whipping eels slide,

over him the tasselled palanquins of Portuguese man-o’-wars

bobbed like Asian potentates, when ribbed dunes hide

the spiked minarets, and the waving banners of moss

are the ghosts of motionless hordes. The crabs’ anabasis

scuttles under his wake, because this is the true element,

water, which commemorates nothing in its stasis.

From that coral and crystalline origin, a simply decent

race broke from its various pasts, from howling sand

to a track in a forest, torn from the farthest places

of their nameless world. With nothing more in his hand

than the lance of a spear gun, fishes keep shifting

direction like the schools of philosophers,

and cautious plankton, who wait till darkness is lifting

from the Antillean seabed, burst into phosphorous

meadows of stuttering praise. History has simplified

him.

I should mention that I happen to know the “Portuguese man-o’-wars” that appear in this passage—“bluebottles” we call them at home, they’re small but powerfully stinging jellyfish that blow in from the Great Barrier Reef on a nor’easterly wind (so, from roughly the direction of the Caribbean!) and they really pack a punch while you’re out in the surf; I was stung quite badly by one when I was about 7, while doing ‘Nippers’ (junior surf-life-saving, an Australian summer sport), and several times since. So there’s an example of that personal resonance with the setting of Omeros I was talking about.

In these lines the sea-floor metamorphoses into a kind of classical scene; “stoas” are those Greek long colonnades, but here they are the corals through which the “whipping eels slide”; the jellyfish glide by like “tasselled palanquins”, those beds on which “potentates” (like I imagine Cleopatra) were carried by slaves; and there’s that wonderful image of the fish changing directions, “like schools of philosophers”. So the coral bed turns into ancient Athens before our eyes; it’s almost like what today we’d call ‘augmented reality’. Generically it’s not dissimilar to Ariel’s Full Fathom Five song in The Tempest.

Yet at the same time—and this is the critical point—the poet first acknowledges that these classical resonances are an imposition on the landscape, a kind of ‘parodic architecture’, he calls it—which is of course a comment on the entire premise of the poem, its own inherited architecture, that of the epic mode and the English language. But this imposition, the poem argues, is ultimately a viable one, for it comports with a tidal conception of history, “the fluent sculpture of Time”, that like water “commemorates nothing in its stasis”.

CB: Can you say something about the importance of Achille’s visit to Africa in Omeros, in which he meets his own ancestors?

JS: Well it’s interesting, because Walcott himself visited Africa, but only after he had written Omeros. He said in an interview with Christian Campbell [in 2010] that in a way he may have been anticipating his own journey to Africa in writing of Achilles’ return there, something that writers strangely do, anticipate their future in some way, even if they don’t know it. And I mean, it’s there already in A Far Cry From Africa, which is much earlier. Walcott rejected the notion that his later visit to Africa was representative of some monumental ‘coming home’. And yet, for Achille it is that, and he does do that.

CB: He does do it, and is changed as a result, and Philoctete can be healed.

JS: Yes, perhaps Achille’s visit to Africa—it does seem actual, but is it principally imaginative?—paves the way for Philoctete’s healing, and helps to fulfil the promise of the healing of “the wound”, which is a major theme in the poem. That healing passage, when Philoctete is bathed by Ma Kilman, is astonishing; let me read from it (from XLIX.1):

She bathed him in the brew of the root. The basin

was one of those cauldrons from the old sugar-mill,

with its charred pillars, rock pasture, and one grazing

horse, looking like helmets that have tumbled downhill

from an infantry charge. Children rang them with stones.

Wildflowers sprung in them when the dirt found a seam.

She had one in her back yard, close to the crotons,

agape in its crusted, agonised O: the scream

of centuries. She scraped its rusted scabs, she scoured

the mouth of the cauldron, then fed a crackling pyre

with palms and banana-trash. In the scream she poured

tin after kerosene tin, its base black from fire,

of seawater and sulphur. Into this she then fed

the bubbling root and leaves. She led Philoctete

to the gurgling lava. Trembling, he entered

his bath like a boy. The lime leaves leeched to his wet

knuckled spine like islands that cling to the basin

of the rusted Caribbean …

There’s an accumulative force here and throughout the poem; the lines really gather heft as you’re reading them (not unlike the way the hexameters in the Iliad hurtle along like a cavalry charge). The weeping sore of Philoctete’s that Ma Kilman is trying to cure him of here is of course also the wound of colonial history in the Caribbean; the cauldron-bath (a relic from the sugar mill) is itself also a kind of gaping wound, mouthing “the scream of centuries” and it is encrusted with “rusted scabs”. The bathing of Philoctete is, I’d say, almost baptismal. That image of the “lime leaves leech[ing] to his wet knuckled spine like islands” is so corporeal and vivid, and again takes me back to my own bay of islands in Australia, Moreton Bay. Perhaps above all, this passage is a brilliant example of Walcott’s ability to shift, in a mercurial way, between micro- (leaves, bath, body) and macro- (islands, ocean, history) images and concerns, and to keep all these balls in play at the same time, often in the same passage or even line.

CB: If I could just give a few quotations from him and get your response?

JS: Yes – well, I will try!

CB: In his wonderful essay, “On What the Twilight Says”, he observes the unreflecting calm of a group of Trinidadian fishermen and says: “By all arguments they should have felt displaced, seeing this ocean as another Canaan. But that image was the hallucination of professional romantic writers and politicians”.

And in a different essay, “The Muse of History”, he writes: “fisherman and peasants know who they are, and what they are, and where they are, and when we show them our wounded sensibilities, we are most of us displaying self-inflicted wounds”.

JS: To me both of those remarks show how acutely aware he was of the risks of his own position as a foreign-educated poet (having studied at Oxford) tapping into these grand European traditions, and the hazards of using them to articulate the Caribbean experience. This is also something of a classic move of the poet, to acknowledge his own separateness from the people he is writing about. And by separateness I mean his immersion in a certain set of poetic discourses to which the people he writes about – the fishermen, say – aren’t privy.

I’ve experienced this situation first-hand. All of my uncles on my father’s side are fishermen and trawler-men by vocation; one cousin once said to me, “oh Jaya I’m not smart like you, I didn’t go to university”; I said to him, “Put me on one of your trawlers, we’ll see who’s smart and educated, and who’s not!”. It was they—not Homer—who taught me that you can, and sometimes must, read the sea – it’s one of the great texts.

CB: As Walcott was well aware.

JS: Absolutely. So I think in those passages he’s exerting a critical force on his own knowledge of the archetypal discourses of maritime epic and empire, because he understands how that knowledge also defines ‘the wound’ that is the legacy of those two related things; so ‘the wound’ is a self-inflicted one to some extent, or perhaps the ‘wound’ is also his knowledge in some way. But this is a deeply nuanced point. In its simplest form, for me anyway, it’s like he’s saying, ‘hey, my fisherman friend here has no idea who Homer or Virgil was, or Dante. What’s it to him? And what’s it to her, the curing of Dante’s wound by Beatrice’s smile and the forgiveness of his sin?’ It’s a great question, and we could be here all day discussing it, just as he spent his life writing about it.

CB: Let’s assume that the audience for this interview knows a fair amount of poetry, and let’s imagine that they have in fact never read any Walcott. Where would you recommend they begin?

JS: There’s a few different Selected and Collected Poems; or why not just read Omeros? There’s a host of poems that are often anthologised, and these can be a great way in too.

CB: Can you name a few?

JS: As I mentioned, The Gulf has been a recent personal favourite. In addition to A Far Cry from Africa, by far his most anthologised poem, I think also of poems like The Glory Trumpeter, The Sea is History, The Season of Phantasmal Peace, Love after Love... But I do feel Omeros is as good a place to start as any; as an epic its canvass is much vaster than that of the individual poems, and you’ll be with it for some time. Then again, sometimes I wonder whether I’m drawn to it just because that lapping of the water is also in my blood. And probably yes, it is in part because of that.

CB: But is it there in all his poetry anyway, are you even able to get away from it?

JS: Yes, it’s something of a pulse throughout his work, and no you’re not going to be able to get away from that!

CB: Would you like to make any concluding comments?

JS: I guess I’d just add that, as we’ve been talking, it’s occurred to me that the experience I described at the start, of happening to be reading a poet as he was dying, but only realising it afterwards, will probably turn out to be a rare one. In a way it was a privilege, because the intensity of that strange, distant mourning I experienced helped to sharpen some of my thinking about what poetry can do—we’re always questioning the value of our art. When I read of Walcott’s death and thought, you know, ‘sheesh, I was with him’, I was convinced in that moment that this wasn’t a metaphor; that in a sense I was with him. I figured there must’ve been others too, who by chance happened to be reading him in his final days, and I recall thinking of this image of us, his last readers in his lifetime, gathering around him on his deathbed, as if we were on some other plane. It just rammed home to me the idea that strong poems can be especially good at connecting the two sides of a gulf—be it spatial (the near to the far), temporal (the future to the past) or ontological (the living to the dead)—and that this is something of a miracle, given the tyranny of distance and the finality of death. Literature might not often be as immediately affecting as music, or have the physicality of the visual and the plastic arts, but it can speak across the gulf to you in a way those art forms can’t quite. At first I was saddened by the thought that he couldn’t have known how his work was connecting with readers and writers in his last moments, that poets will never know that—but do they? Maybe the great ones do a little bit.

CB: Thank you very much Jaya.

JS: You are very welcome.