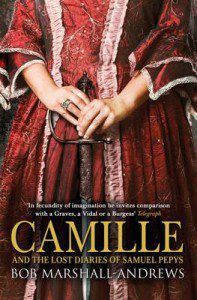

2016, 338 pp, Whitefox Publishing

Last Tuesday a novel was launched in Carmelite Chambers. Trust its author – Criminal QC and former Labour MP Bob Marshall-Andrews – to work in a former nunnery, with some of the best views in England. But it was the right place for this novel, which is so deeply embedded in London soon after its Great Fire, and set so much in the environs of these Chambers. It is right that the Chambers look across to Bankside – so associated with the theatre, in turn so important to the novel. And right that they possess a view of the Thames, representing the connection between England and Abroad, on which the novel also turns.

The heroine is a half-English half-French actress and duelist of the time of Louis XIV, which is also that of Samuel Pepys. Because she (justifiably) kills a French aristocrat, she becomes a refugee in England, where she dumps the male dress that she had adopted to escape, assumes an English pseudonym, and finds a job as Pepys’s amanuensis just at the time that his eyesight is failing. His diaries therefore do not stop when we think they do, but (as the manuscripts which Marshall-Andrews astonishingly discovered during his researches at the Bodleian library reveal [they have alas since been lost again]) continue through Pepys’s dictation to Camille.

This happens to occur during a sensitive period. Charles II employs Pepys to negotiate the 1670 Secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV. According to this Treaty, which remained unacknowledged for a century, Louis provided Charles with funds in return for the latter’s toleration of Catholics, and British support for the disastrous French war against the Dutch.

In Marshall-Andrews’s speech at the launch he wickedly likened Charles to Blair, Louis to Bush, and the War against the Dutch to the Second Iraq War. Wickedly, because the novel’s politics contradict this analogy. They are very much on the side of Charles, Pepys, and the latter’s sidekick John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester (for whose presence in the novel I am proud to have been responsible) – against the English Puritans, who represent so much of which Bob disapproves. The bias is so strong that the First Earl of Shaftesbury becomes a villain, and the Secret Treaty is presented as not such a shameful thing after all.

Like Marshall-Andrews’s previous historical thriller The Palace of Wisdom (set in the same period but the still more dangerous location of Florence during the last gasp of the Inquisition), the pace is fast, the stakes are high, the sense of time and place vivid, the violence at times hugely moving, and the humour rich and frequent. Here is how Pepys first appears in Camille’s narration:

‘At first I could not see his eyes because his wig had been knocked sideways by the lintel of the carriage door. When I did see them it became apparent why he had unnecessarily struck his head. Although wide-set and even handsome, they were drawn into the tight squint which signifies a serious myopia. Because of the wig he did not see me and practically handed upon me, muttering a carnal oath while he readjused his hairpiece. He fell into the seat opposite and, his wig reassembled, noticed me for the first time. When he did so the squint increased and he jerked his face forward in order to better focus on me or, I suspect, my cleavage, over which, instinctively, I placed a gloved hand.’

Given that to anyone who knows Marshall-Andrews it is obvious that he identifies with Pepys, this shows a loveable willingness to make fun of himself – which continues throughout. Pepys appears particularly ridiculous when he becomes sea-sick on a rough crossing into France:

‘Pepys was immediately sick and vomited consistently for the next four hours. At first he clung to the ship’s rail and then, ill-advisedly, attempted to negotiate the ladder to the lower deck. Without his spectacles this would have been a considerable feat in flat calm. In the existing circumstances it was a disaster. He lost his footing, clutched at the hand rope and then swung helplessly beyond the reach of one of the crew clutching desperately at his ankles. […] Exerting my not inconsiderable strength, I hauled him back to the ladder at precisely the moment when the boat pitched violently backwards causing the oak sidebar to strike him with great force between the open legs. The agonised scream was cut short by another headlong pitch of the boat, which drove his face straight into my corseted bosom. There it remained muttering muffled groans until the crewman, who now had him by the shoulders, hauled him back onto the deck. With that assistance and mine, he was returned to the boat’s rail, where he hung helplessly retching into the roaring wind.’

Being both Pepys, and a Marshall-Andrews avatar, he is cheerfully carnal as well as completely decent, and his relationship with Camille teeters towards an affair. I shall not report on whether it reaches it; that is for readers to discover – along with an episode concerning Camille’s brother which I find as almost unbearably painful to read as it apparently was to write.

I will just say that this novel is further evidence that Marshall-Andrews is a National Treasure – a man deeply connected to English history, and strongly on the side of its most liberal, generous, decent, and life-loving elements.

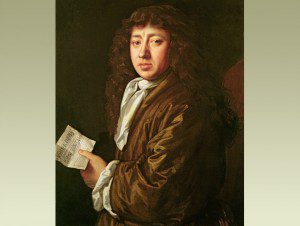

Samuel Pepys at the time of the Great Fire (shortly before he meets Camille), by John Hayls