Over the last three months I have visited Athens three times. This is my retrospective diary of life and death.

Mid August 2018

I have just returned from a week’s visit to my parents-in-law. It was wonderful, but Athens in the summer is never entirely easy. The city has sucked in much of the country’s population since the Second World War, as the economy has expanded with the equivocal help of EU credit and structural funds. From the Areopagus, where Paul converted the future Saint Dionysius and unknown others to the worship of his unknown god, one sees the city sprawling miles across its basin and well up its ambient mountains.

Fortunately, a breeze blew through the week, softening the sun and dispersing the fumes. This was my first visit as a vegan, and I was pleased to find the term well understood, and the cuisine accommodating. A khoriatiki (farmers’/Greek) salad turns out to be worth eating sans feta, and dolmades, if vegetarian (as they are in their summer incarnation) are also vegan. I used olive oil generously, in the conscious if unscientific hope that each spoonful would add a day to my life, and that I would – by the time my husband and I retire to a yacht with a parrot, two cats, and two golden retrievers at the very least – have acquired a Greek longevity. I hope that ouzo is vegan; it is the only form of alcohol that seems to work well – or at all – in the heat. No wonder that Greeks don’t have an alcohol problem. Happiness, under that sun, is not improved by pouring disruptive fluids into the precise and subtle mechanism that is the brain.

This time I finally cracked the double consonants. These one has to learn by rote (an ‘m’ followed by a ‘p’ is pronounced ‘b’; a ‘g’ followed by a ‘k’ is pronounced ‘g’; a ‘t’ followed by an ‘s’ is prounounced something between ‘ts’ and ‘ch’). Beyond these exceptions, I pronounced Latin letters as in English, Cyrillic letters as in Russian, and anything I didn’t recognise, or which appeared to be the second of three consonants in a row, as an ‘i’. That seems to do the trick. The spelling reforms under Papandreou in the 1980s were a botched job. The stress accents were simplified, but multiple letters remained which were pronounced identically as ‘i’ (hangovers from Ancient Greek letters which were pronounced differently), and double consonants were left with their indication of a hard consonant (because Ancient Greek consonants had softened over time). A proper spelling reform, such as the Bolsheviks enacted in 1917-18 when they slashed the Russian alphabet by four letters to thirty-three, would probably actually require a Communist revolution in order to be carried out. As it is, when my husband and I encountered monuments inscribed in Katharevousa (the formal Greek that still today is used in the law, parts of the army, and the single most reactionary newspaper), he has difficulty understanding it (he finds Platonic Greek easier), and is thus excluded from the act of remembrance that the monuments were supposedly created to enjoin.

I spent many happy hours in the Vasilikos Kipos, the former royal gardens (now formally the ‘Ethnikos Kipos’, or people’s gardens) behind the former royal palace that is now the parliament building on Syntagma Square. I went there each day to read for a paper I will give in early September in Tula (Russia) for the 190thanniversary of Tolstoy’s birth, concerning Tolstoy’s hostile relationship to Shakespeare in the context of nineteenth-century Russian Bardolatry. And so I read Tolstoy’s plays (not at all bad), Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk Province, Turgenev’s Hamlet of Shchigrov District, and his extraordinary King Lear of the Steppe, under unSiberian palms, surrounded by the descendents of the people who in the nineteenth century were far too busy fighting the Ottomans, with Russian help, and coming into national being, to suffer an excess of what Turgenev condemns as ‘Hamletism’ (vibrantly intelligent, sceptical, cynical, neurotic, navel-gazing intertia – in contrast to ‘Don Quixotism’, its diametric opposite, both heroes having remarkably been born in the same year of 1605). Meanwhile, the mosquitoes who teem in the Kipos steadily ate their way into my legs, my arms, my feet, my hands, my face. They, not the heat, were the limiting factor which would eventually send me on my way back home up Lykavitos.

One late afternoon, my husband and I planned to walk through the Kipos to Plaka. At its North entrance a sign told us that the gates would be locked at sunset. The sun not being unambiguously about to set – whatever, according to meteorologists, that might precisely mean – we decided to risk it. And thus it was that we had the experience, which I feel makes us thoroughly Athenian, of having been locked into Greece’s national garden at night. We wondered about through sixteen hectares of cats and cicadas and giant fleshy leaves, all rapidly turning grey, until we encountered two joggers. One seemed perfectly at home in the garden, and to have no plans of any kind to leave. The other was the kind of youth for whom vaulting over high, spiked iron railings poses no difficulties, or at least no terrors, and who intended to escape in precisely that way. Which left us. After trying successive exits in turn, we ended up back at the North entrance. Fortunately there was a newsagent’s booth within waving distance along the pavement. We stretched our arms through the railings, Hansel-and-Gretel-like in our witch’s cage, and managed to solicit the shouted advice to try the one exit that we hadn’t visited, on the North-East side. And so we trotted, Hansel-and-Gretel-like, back into the dark, round the pond with the enormous carp, past the bench where I’d read The Power of Darkness, past the Roman mosaics uncovered when King Otto’s Queen Amalie had the park set out in 1840, to the gate where an unamused but unreproachful policeman silently opened the gate and set us free.

So the days passed well, marred only slightly by the constant shock of prices. This had started with the flights. It is an infuriating fact that Athens is far more expensive to fly to than other South European cities – or indeed Moscow – and is instead on a par with New York. I inquired as to why. It turns out that, in the context of the recent Greek austerity, Lufthansa bought Elefterios Venizelos Airport – and has since then been extracting its bleeding pounds of flesh through airport taxes, which are passed on to customers. It was part of the deal that no other airport would be allowed to operate in the vicinity of Athens, so that it would not be undercut by cheap flights operating from elsewhere. Instead, budget operators (EasyJet, Ryanair and Wizz Air) offer uncomfortable flights to Athens at non-budget prices, whilst British Airways offers standard-class flights at first-class prices. This contract has years yet to run. Meanwhile – quite apart from the fact that, due to the Brexi-shambles that bewilders all Greeks, the pound is running one-to-one against the Euro, and the Eurozone suddenly feels like Scandinavia in its expensiveness to Britons – Greek wages and prices seem catastrophically unaligned. A litre of oat milk and a small bag of muesli cost me £/€10.50 at a central Athens deli. Admittedly it was central, and admittedly it was a deli, but it is still questionable whether it was right for Greece to enter the Euro when it did, and whether it is right for it to have remained in it now (the people having rejected the last EU bailout).

One of the major subjects of conversation was the wild fires, which had not yet been put out East and West of Athens, but were strangely unnoticeable in the city itself. The nearly hundred deaths were not understood by Greeks as the unavoidable results of what the insurance companies term Acts of God, but as the avoidable results of incompetent and corrupt acts of man. In particular, Mati, the worst-afflicted resort in East Attica, was being felt as what I would term the Greek Grenfell. Uncontrolled residential building had been permitted, as a result of which the perimeter walls of many houses impeded the routes to the single path that ran down the cliff to the sea. Some people who tried to escape Mati by car found themselves being redirected by police stationed South of the village back to the village itself. There they piled up in confusion. Some people were burned in their cars. Others were burned on the streets after abandoning them. The emergency services did not communicate properly with each other. The anger felt is tempered merely by cynicism. The people expect more Grenfells in future summers.

Homelessness rates are higher than I have ever seen them in Athens. Walk from Syntagma down Ermou to Plaka of an evening, and you see bodies everywhere, on benches, walls, even roads. ‘Who are they?’, I ask. ‘Are they refugees?’ ‘They are Greeks’, my husband answers. The reason seems to be this: Greece receives EU funding to shelter the refugees coming to Greece from elsewhere. It receives no such money to shelter the Greeks made homeless by the EU-imposed austerity. My brother-in-law works at one of Athens’ refugee camps. One day his daughter, who was volunteering there for the summer (as many students from across Europe do) took me around. I was relieved and impressed. In contrast to the refugee camps on, say, Lesbos – which are overwhelmed – this one, created in 2015 precisely in order to relieve such camps, is well-run, and nearly as orderly as such places can be.

About two thousand refugees live in portacabins, each of which has washing and cooking facilities. There are separate cabins for laundries, cafés, CV workshops, and language classes. Formerly food was handed out, but this was not popular with the refugees, who now receive allocations of money instead. Interpreters are provided (although only in the recognised languages, which do not include Kurdish – ‘nobody wants a row with Turkey, Iraq or Syria’, my brother-in-law explains). There is a football pitch, which the Africans in particular use with enthusiasm, and where the people of other nations gather to watch them play in the evenings.

Most remarkably to a British person sadly used to the concept of ‘deportation centres’, which function in the UK as prisons for refugees, the residents can leave whenever they like. The children must attend Greek schools; the adults may find jobs. The struggle is in the opposite direction, to get in. A place here is much valued, and those refugees in Athens who have not been allocated to a camp try to get past my brother-in-law (who works on the door), or else to climb the perimeter fence (falls from which he regularly deals with).

In this camp there are around 450 Afghans, 400 Syrians, 150 Iranians, 150 Africans (of many countries), 110 Iraqis, 50 Pakistanis, 40 Palestinians, and 40 Kurds (not officially classified as such). Many, but not all, are middle-class, especially those from Iran. Though there are many families, the camp is 60% male, since it includes many young, unaccompanied males, especially from Pakistan. The women are hardly seen; they tend to stay in their huts. The residents’ processing by lawyers is slow, because the latter, like many of those working for the Greek state at present, are not paid properly or regularly. Security is not as tight as it might be, because there is insufficient money to pay for airport-style security; hashish and knives therefore exist in the camp, and influence its life. The lingua francas are Greek and English, but my brother-in-law estimates that 90% of the women can’t speak either language, and many of the Africans are Francophone.

If the Greeks are stressed and angry about current circumstances, this isn’t apparent at street level. People chat over expensive coffees at pavement cafés with every apperance of calm. Yet if you walk at night along Odos Irodou Attikou, which runs down the East side of the Vasilikos Kipos past the Presidential Palace and the Prime Minister’s Palace, you first have to wind past the police vans that block the entrance at both ends. On the street itself you find three kinds of men. First the Evzones, the ceremonial guard who do a Silly Walk (silly even by the international standards of such things) in front of the Presidential Palace dressed in pom-pom clogs and other descendents of nineteenth-century military garb.

Guarding them are the military police, whose guns appear, by contrast, strikingly non-obselescent. Some of these men have moustaches, and these make me particularly nervous, I think because they remind me of the moustaches worn by the Britons who supported the First World War when it came (in contrast to refuseniks such as D.H. Lawrence, who grew proto-hipster beards in protest). Greeks, however, assure me that such moustaches hold no terror for them. The police vans at each end of the street hold dozens more such policemen, sipping drinks, quietly talking, presumably ready to save the Greek democratic government should they suddenly be called on to do so.

The third category of man that spends his nights on Odos Irodou Attikou is dressed normally. They hang out, here and there leaning against walls and railings, smoking, and talking to the men in the second category. They are the secret police. Every evening, my husband and I walked to the Kallimarmaro Stadium (my favourite Athenian structure, rebuilt in 1870 on the site of the original from 330 BC) along this street. One night I asked him, ‘do you think that these guys have noticed us? If we were plotting to storm the Presidential Palace, and wanted to case the joint, pretending to take a couply walk every evening to Kallimarmaro Stadium is exactly what we would do.’ ‘Of course they have’, he replied. ‘They have footage of us. And of course that is exactly what we would do. But we would not do it in the way that we do it. These guys have long ago come to the conclusion that we pose no threat whatsoever.’

On one of our last days, we made a day trip to Spetses, sixty miles to the South-West of Athens, just off the Peloponnese in the Saronic Gulf. We had reached this island by a process of elimination, being already well familiar with Hydra, Porous and Aeghina, among the islands accessible on a day trip from Athens. My husband also had some memory of his father once having had a wonderful experience on this island. And so we went.

I confess that my Northern soul didn’t quite know what to do with Spetses. It is a rich island favoured by rich Greeks that lies across the Gulf from Porto Cheli, which is favoured by even richer Greeks. There is a small town, where one eats, and fails to buy anything from the achingly-expensive shops. There is a tiny chapel in sea colours, where one prays. There is the art deco high society Poseidonion Hotel on the seafront, where one might allow oneself a coffee.

Then there are boat trips around the island. We decided to take one. The island, it appeared to me from the judicious distance which this afforded, is scrubby in a non-sublime way (Mount Hymettus above Athens, by contrast, is scrubby in a sublime way). We spotted a villa which my husband thought might be the model for the mansion in John Fowles’s 1965 novel The Magus (it later turns out not, and in any case I haven’t yet read this novel).

The boat stopped at a tiny beach, and we scornfully declined to descend in order to roast ourselves on time-metered sunbeds. The boat then stopped at another beach. And this time we noticed that we were the only people remaining on board. We called to the captain. He told us to get off. We told him we wanted a round trip back to the port. He said that the package required all passangers to descend at one or the other beach, to be picked up again four hours later. We were uninclined to get into fights with Greek kapitanioses. And so there we were, without swimming clothes or any desire to swim, hungry and with only snacks available to buy, and without the possibility of hitching the six miles back to the port because all motor cars except taxis are banned from the island, and everyone uses motorised tricycles which look amazingly fun but cannot possibly take two hitch-hikers. Fortunately, after half an hour’s disconsolate wait at a bus stop that was unused since it was the middle of the siesta, a taxi happened to drop off some tourists at the beach, and we took it back to the town in relief if at exhorbitant cost.

There we decided to take a horse-and-cart ride, which took us through complexes of silent, walled villas. The life of this island is private, I decided, and it does not include us, who are manifestations of the public. My husband, who has a Greek soul for all his years in London, was delighted by the beauty and the peace.

The closest I got to swimming.

That evening, my father-in-law Spyros turned raconteur. ‘When I was a boy’, he said, ‘fifteen years old, I was on holiday with my parents in Porto Cheri. At a party I met the daughter of the Italian ambassador. She was called Mercedes, and she was beautiful. Really beautiful. She was twenty. She had black hair and amazing, strong eyes. She was staying with her parents at the Hotel Poseidonion on Spetses. And so I made a bet with my friend that I could swim the seven kilometres over to Spetses. He decided to join me in trying. But one kilometre out, even though he was older than me, he turned back; he couldn’t swim any more. But I carried on. I got all the way to Spetses. And there I got taken onto a yacht where there was a party that night. Mercedes heard of what I had done for her, and she came to me. She took me by the hand and danced with me. She took me to the front of the boat, and kissed me.’ ‘And then?’ asked one of the guests who was present that evening in Kolonaki. ‘Then nothing’, interrupted my mother-in-law Alexia with decision. She, only half irritated; Spyros flushed with amusement, pride, and life.

*****

Late August 2018

On the 23rdof August, not long after we had returned to London, Spryos died. There was a complication with his lungs, but there had also been the strain of looking after his wife, who had dementia. He was, we think, ninety-one. He had lived through the Nazi occupation of Athens, when he had played a boyish role in the Resistance, and pursued left-wing politics after the War. He had been exiled by the Junta, had returned to Greece after the Junta fell, became a founder and the Chair of the Cultural Capitals of Europe scheme, and in his last years had seen his country fall back under immense strain. He loved his country, and his wife, dearly.

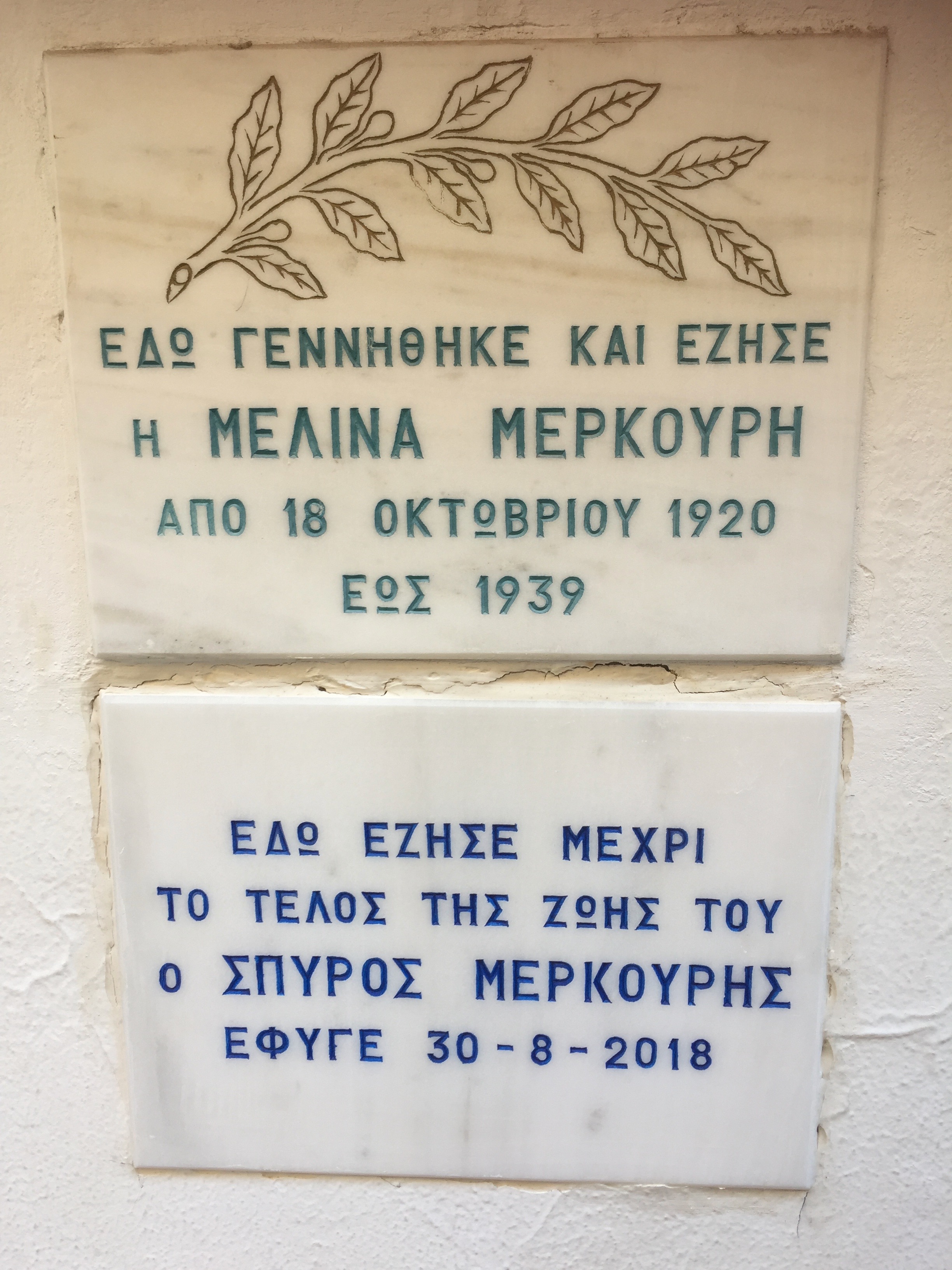

The funeral took place on 27thAugust at the First Cemetery of Athens. Alexia was not well enough to be there, but she knew that it was happening. The great and possibly-good of Greece were invited. The Minister of Culture came (Spyros’s own sister, Melina, having been Minister of Culture for nine years in the eighties and nineties); Alexis Tsipras sent a wreath. At Spyros’s own wish, he was cremeted. This being illegal in Orthodox Greece, his body was sent to Bulgaria for cremation, and his ashes will be scattered on the Aegean Sea.

From a newspaper

The lower plaque joined the upper on the family house on Odos Tsakalof, Kolonaki

The next day, my husband and I visited the Melina Mercouri Café in Plaka. There are no photos of her brother amongst the dozens of Melina that cover its walls, but it felt like the right place to be. The proprieter recognised us from previous visits, had read of our bereavement in the newspapers, and showed great sympathy. ‘Now,’ my husband mused, ‘I am “head of the family”. But such things don’t mean anything any more.’

*****

Early November 2018

Just over two months later, on 28thOctober, Alexia joined her husband. Her health had failed rapidly after a fall she had had in 2017, and she had progressive dementia. And yet, just weeks before she died, she gave an interview for a forthcoming documentary about the real lives of the Durrells and those who knew them, after the period in 1930s Corfu which was documented by Gerald and Lawrence. Alexia, the only child of Theodore Stephanides, and main playmate of Gerry in that period, was the last surviving person who remembered the Durrells in paradisial pre-War Corfu. This interview – whether or not it is eventually considered usable in the documentary to be broadcast next spring (apparently she enjoyed the interview, and could still remember much about the time) – is the last footage of her.

Her funeral was also held at the First Cemetary of Athens, but since, as she had made increasingly clear (she had an icon corner by her bedside), she was Christian, she was buried with Orthodox rites. From an outbuilding we followed her coffin into the cemetery chapel. In humane contrast to Russian Orthodoxy, Greek Orthodoxy has seating, so we sat around the coffin as the Priest and his two helpers sang the service through. My husband could understand scarcely a word of this church Greek. Unlike at Spyros’s funeral, where nobody had, it seemed, known quite what to do, here all was confident and organised. The funeral service is identical for everyone. It would have been the same had Alexia been Greece’s President or a little child. That, I remembered, had been one of the factors that had attracted my husband and I to the idea of getting married in Greece (we eventually married in my mother’s home church in Germany): nothing can be customised. All souls are equal. The service reached its end. The coffin was taken up again, and carried on a long last walk through the cemetery. Near the North East side a plot, narrowly between two other graves, had been excavated, and there Alexia was laid.

Three days later, according to Orthodox custom, my husband and I returned. It turned out that the North side of the cemetery is much closer to our house than the South-side main entrance, and that there is a small gap in the wall just metres from where Alexia is laid. A tea-light was burning in a lantern on the earth, and we wondered who had put it there. A cat walked past, and as I looked up, and my eyes focused on cats, I could see dozens of them. Almost every grave was attended by at least one cat or kitten. Alexia loved cats.

As we walked towards the exit, we were suddenly addressed by an elderly woman. She recognised me from the funeral, and knew exactly which grave we had been visiting. I have hardly ever met a more Dickensian figure: she is the woman of the cemetary. She lives there, and tends to the graves and cats. It was she who had kept the candle on Alexia’s grave burning. She offered me her phone number. Wanting to make sure I had typed it correctly, I showed her my phone, but she pushed it away. My husband explained that she is illiterate, as many Greeks of her generation are. We left the lady of the cemetary, the cats, the candle and Alexia behind – but ever under the Greek sun – and came back out through the small hole in the wall into the land of the living.