Report of the Thirteenth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Anthony Pacitto

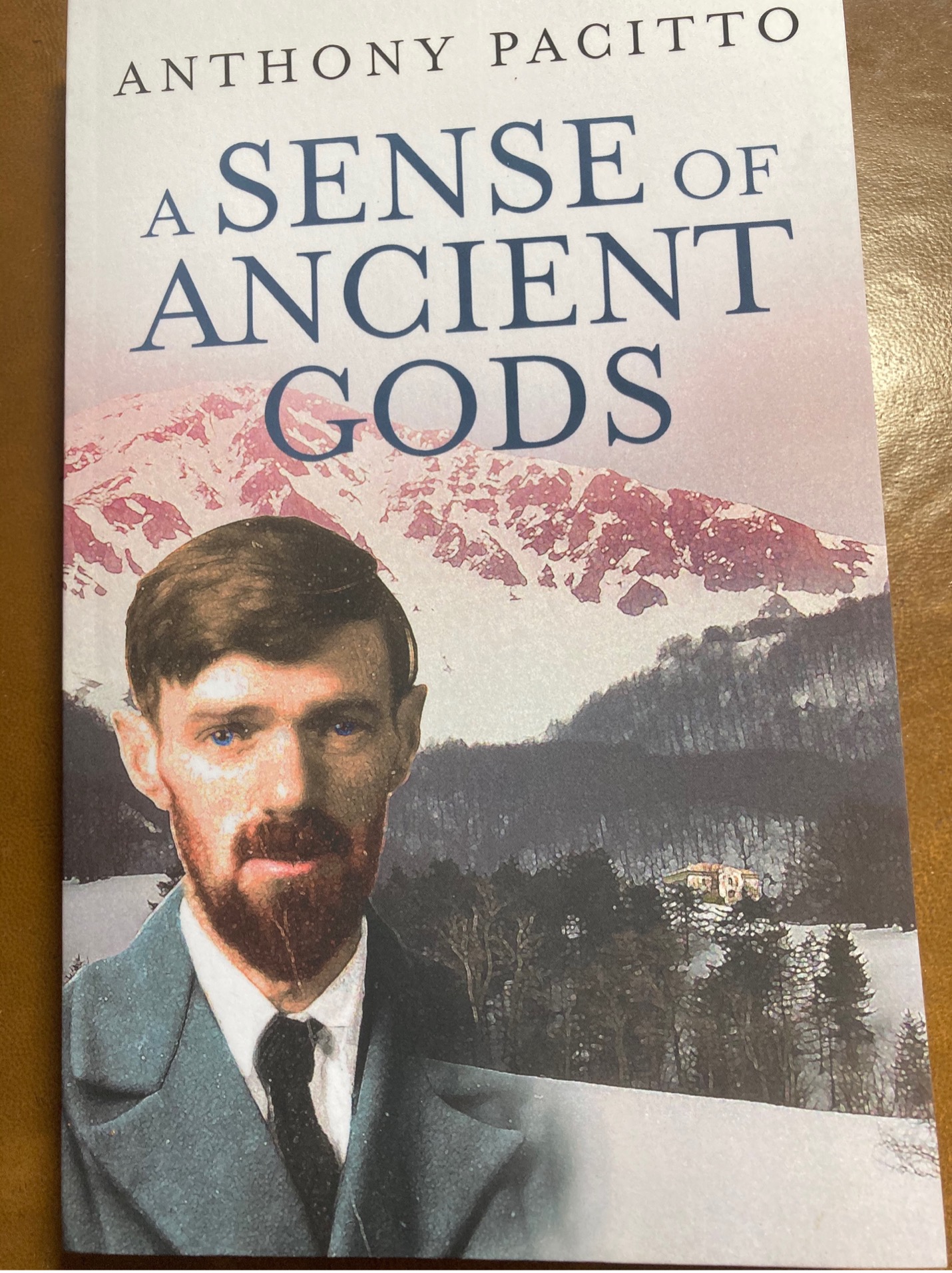

A Sense of Ancient Gods

Thursday 28th January 2021

By Zoom (during period of Coronavirus lockdown)

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Twenty-nine people attended including, from outside of the UK, Justin La Point from North Carolina, Mark Prisco from New Zealand, Judith Ruderman from North Carolina, and Kathleen Vella from Malta.

INTRODUCTION

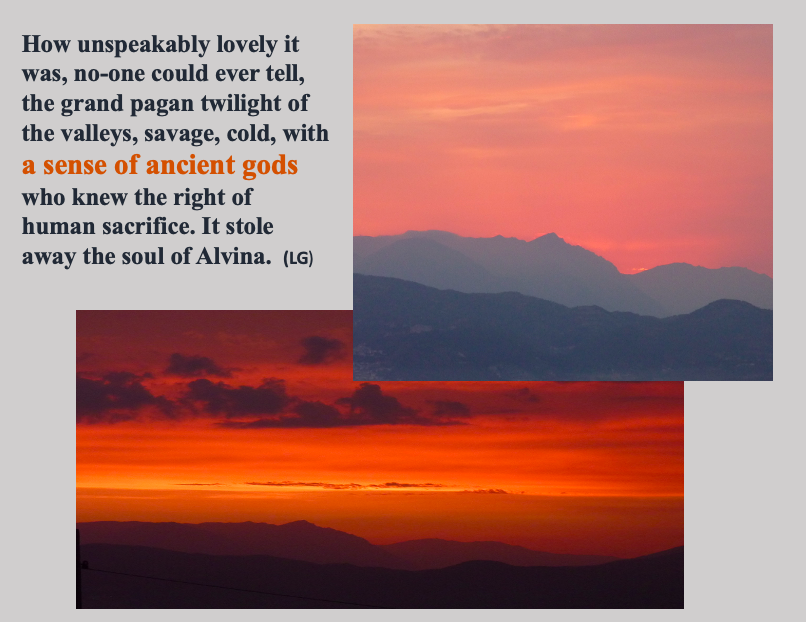

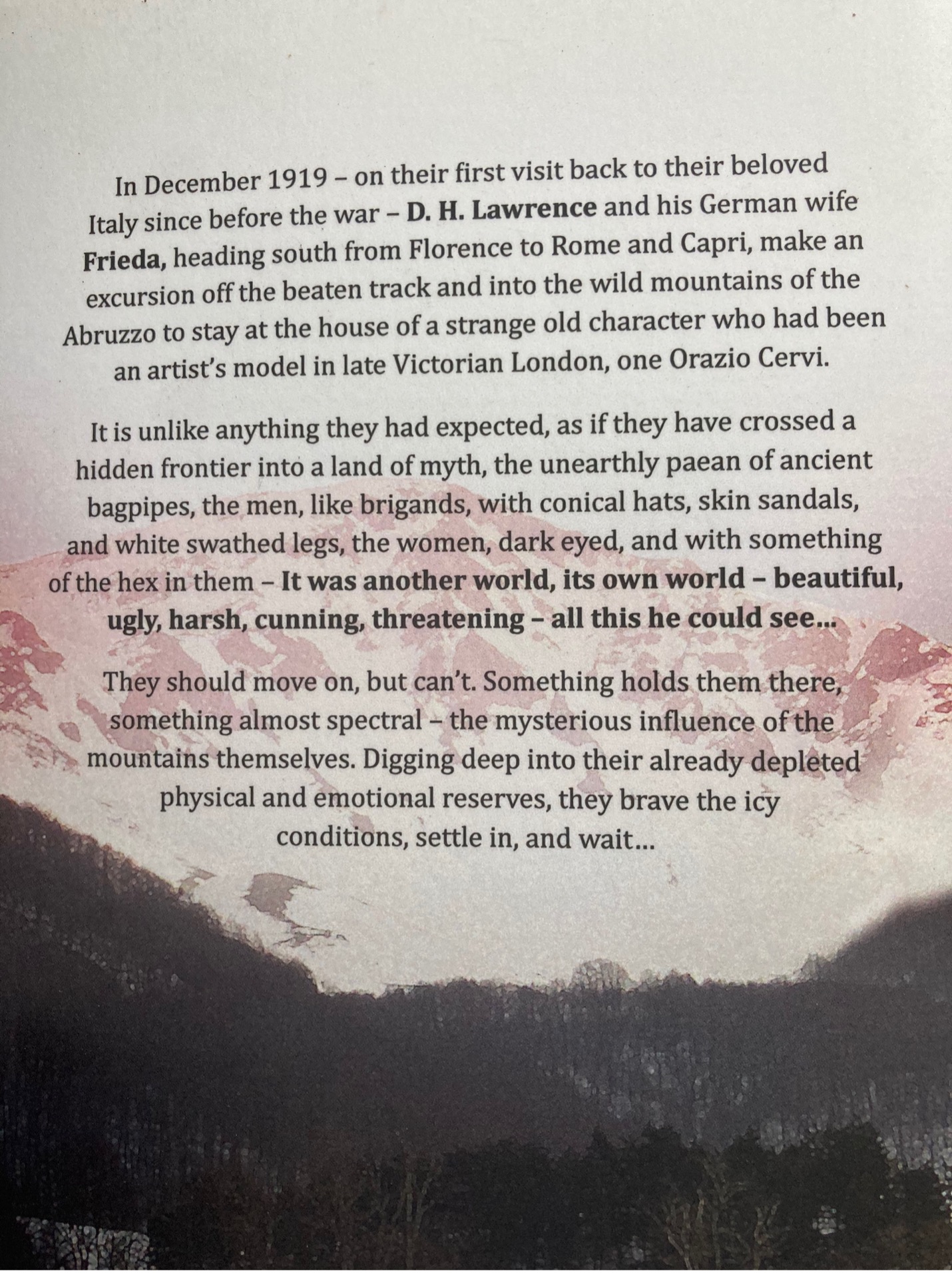

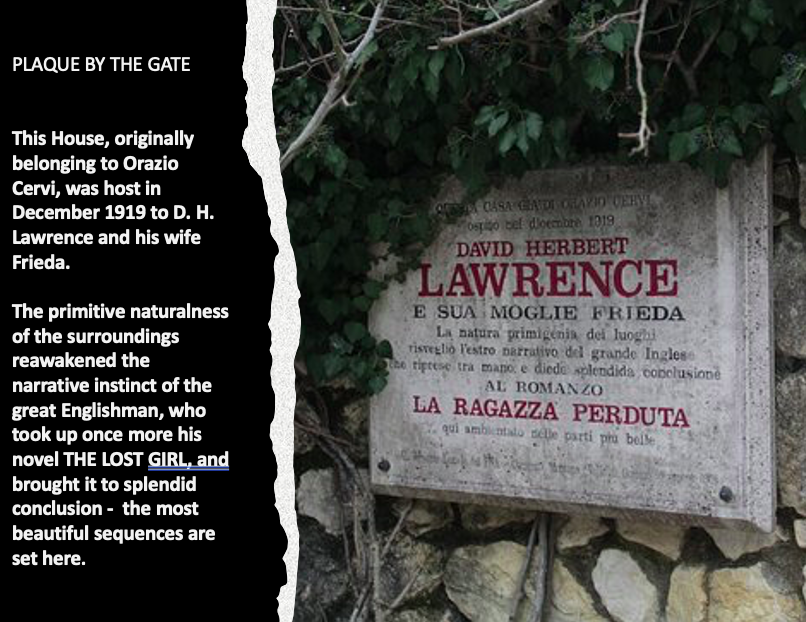

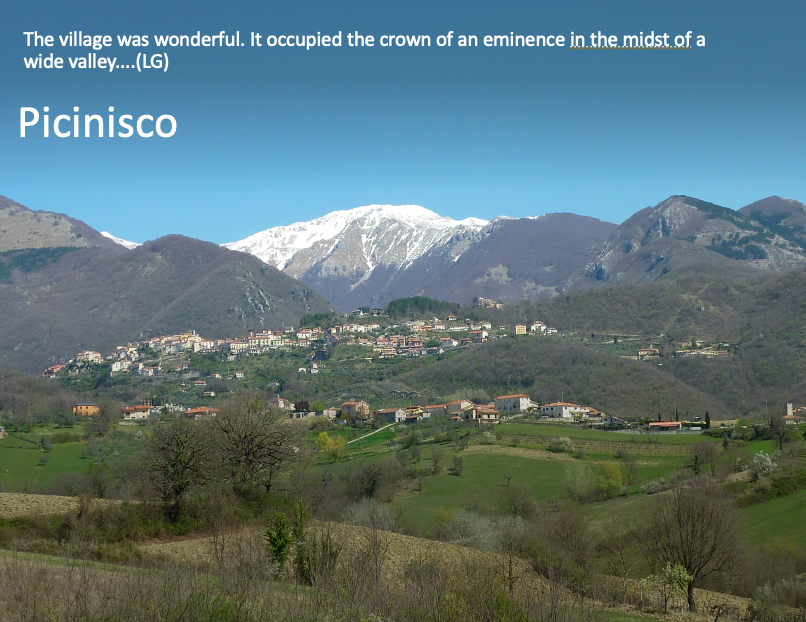

A Sense of Ancient Gods is a 2018 novel that imaginatively reconstructs the nine-day stay which Lawrence and Frieda had with one Orazio Cervi in December 1919 on their first journey outside England since the War.

Cervi had been an artist’s model in London, but had retired to his native settlement just outside the village of Picinisco, in the Abruzzo Mountains in the middle of Italy.

There, on a visit home to his mother, flush with cash and modelling success, he had built himself an ambitious villa.

He married, but, as was common of male Italian workers at the time, left his wife behind when he returned to make more money in London and Paris. She died suddenly, as did his mother, and Cervi, with no imminent reason to return, remained in North Europe for several further years. When he began to lose his looks and therefore his career he retired to the villa, living in cramped circumstances with his silent labourer brother Giovanni. Pacitto represents Cervi as lonely and nostalgic for his past glories in English society: ‘the quondam Englishman, reclusive, alone, nobody to see him slowly fading, the last embers of his London existence gone cold forever … when one morning a letter with an English postmark arrived.’

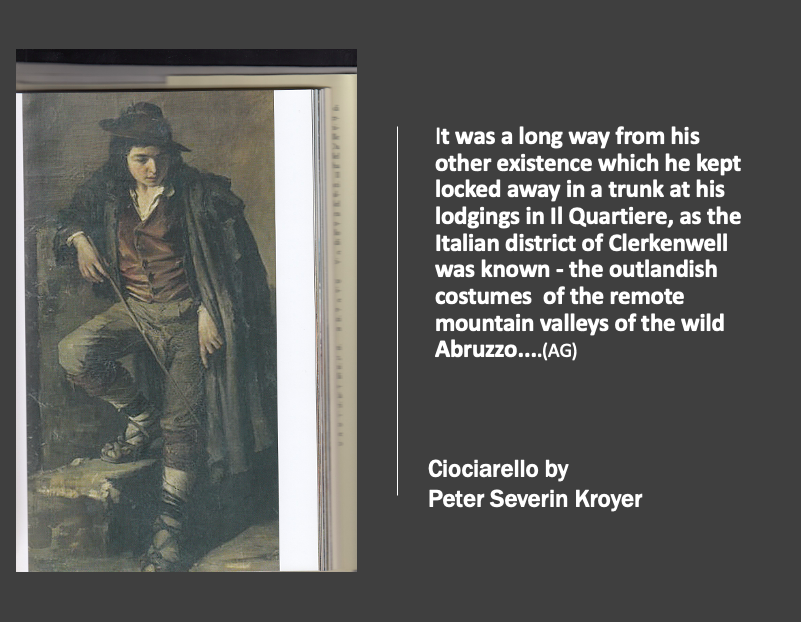

This was from the daughter of one of the artists who had painted him (Sir Hamo Thornycroft), Rosalind Baynes by marriage. She said that she would like to take him up on his long-standing offer to show her his wild, semi-Pagan homeland in the Abruzzo mountains, with its bagpipes and banditti (ie, to South-West Europe what the Caucasus is to Russia).

Man in Piciniscan dress

He assented, but then instead heard from a friend of Baynes, an English writer, asking whether he and his wife might come and stay on their way down to Capri, and send word back to Rosalind on how they found the place.

The novel opens with the morning of Lawrence and Frieda’s premature departure from Cervi’s villa to Capri (the cold and isolation had become too much for them); flashes back to their arrival; then moves forwards through the two weeks of their stay, punctuated by flashbacks to Lawrence and Frieda’s earlier lives, and by beautiful and fraught moments involving various constellations of Lawrence, Frieda, Cervi and Giovanni. It climaxes in a Christmas party before concluding with a section, written partly in the first person by Lawrence, at the Fontana Vecchia in Taormina, Sicily, in the spring/summer of 1920. There he finally finishes his years-long-abandoned novel The Lost Girl, having found inspiration for its ending in Cervi, his youthful nephew (model for Ciccio), the villa, and the Abruzzo mountains.

A running theme is the eponymous Ancient Gods, which Lawrence and Giovanni, in particular, are in tune with/in search of. There are many lyrical passages, with Lawrencian types of insight and vocabulary, but also many that are, also like Lawrence, acutely-observed and acutely-funny – notably the scene in which Cervi is late meeting Lawrence and Frieda’s train on arrival in Atina because he has been warming himself up in the early morning with a couple of brandies:

‘He had wanted to be there on the platform when the train pulled in, wanted to cut a dignified figure – English punctuality for his English visitors. He knew the reputation Italians had for their bad timekeeping, and now the train had betrayed him by being on time.’

Atina market today. In a scene in the novel Frieda buys some wooden toys from just such a stall.

The novel also places a strong emphasis on Lawrence’s and Frieda’s role-play, which Cervi is not always certain about classifying as such. Similarly the reader is not always sure what is based on available sources such as letters, and what is Anthony’s role-playing of the characters’ parts. Either way, it is convincing, and keenly attentive to Frieda’s emotions and thoughts about her marriage which, the novel makes clear, can only in retrospect be seen as assured to last as long as they both should live.

The biography on the book’s Amazon website tells us the following:

‘Anthony’s grandparents came to England from Italy in about 1890. Anthony was born in London, and sent off to boarding school for a proper English education. But in the background another narrative was playing, the images and sensations of early childhood visits to his grandfather’s villa on the slopes of Monte Cassino […] Anthony has a diploma in Italian Studies from the University of Perugia, and a B.A. in History of Art and History of Ideas from Kingston University. He has spent long periods of time living and working in Italy. A Sense of Ancient Gods is his first novel. It has its origin in a gouache of memories from many years ago, […] and the brief burning presence in that remote world of the almost religiously compelling figure of D. H. Lawrence.’

Neil Roberts’ 2018 review of the novel for Journal of DH Lawrence Studies may be found here.

THE LETTERS

Lawrence’s letters covering the period are nos. 1837-1887 in Vol. 3 of the CUP Letters, pp. 412-39. Some of these anticipate his departure for Italy in November 1919, followed by several written on his downward journey, and finally letters sent from Picinisco in December 1919 – ‘Presso Orazio Cervi’. The last one is written from Capri after they have left. Other letters written from Sicily citing The Lost Girl, and partly reproduced in AG, follow on from these.

For examples:

CERVI TO BAYNES

Picinisco Nov.er 12th 1919

Dear Madam,

With great pleasure I have received your letter and I quite understand all you tell me. I am very glad Mr. Lawrence will come first so we may arrange things for your comfort better together with him than I can alone, and if he should not find this place suitable enough for you I would take him to some other place and see if he would like to live there better.

It may be well to give you a little description of this place so you may be able to judge whether it would suit you or not, so I together with Mr. Lawrence may look for another place. This house is about 500 yards distant from the carriage road, and a river has to be crossed by a wooden bridge. The foot roads are not very good in the winter time. It rains a good deal in the winter and we get even some snow sometimes. The climate is much milder near Naples. Here it is nice to live in the spring and summer but you will be better able to judge for yourself when you come. As for the milk, you can get cow’s milk just now, but after Christmas you can get plenty of goat’s milk. You may if you like bring a few tins of dried milk in case of an accident.

I am so grateful to your father for the kind words said to you of me. He and his three sisters have been my best friends all the time I have lived in England and now I will do my very best to repay that kindness I have received from him.

I hope Madam you will get this letter before Mr. Lawrence starts from England. You should tell him to let me know in good time when he takes the train to Cassino so I may go to meet him there. We must arrange how we should recognize each other. I must have at least three days warning so I may be there before him.

Now Madam I wish only to tell you if you would bring a little tea service with you for your own use. It would be convenient as it is not very easy to get good things from here.

I hope Madam you will be able to understand my bad writing a little as I have forgotten a good deal how to write in English.

My shortest and most correct address you should put…

Orazio Cervi

Picinisco, Serre, Caserta, Italy.

And when you are in Italy and want to communicate with me you should put only Picinisco, Serre, Caserta. Not Italy.

I am Madam your obedient servant.

Orazio Cervi

LAWRENCE TO BAYNES

Picinisco, Caserta, Italy, 16th December 1919

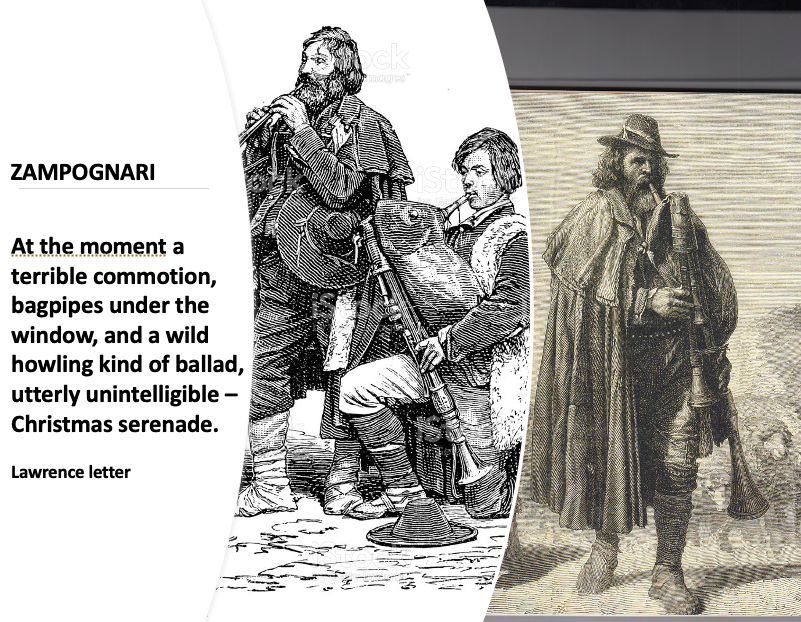

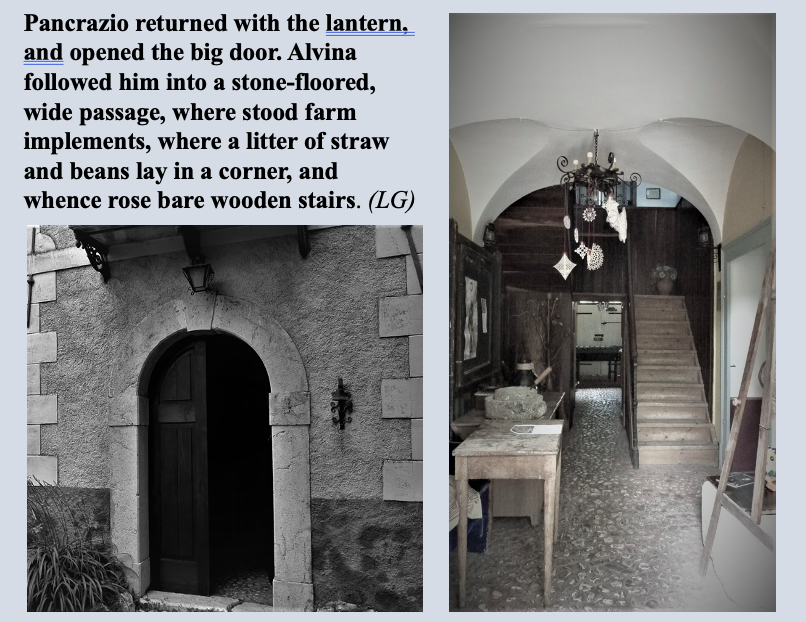

Dear Rosalind: Rome being vile we came on here. It is a bit staggeringly primitive. You cross a great stony river bed, then an icy river on a plank, then climb unfootable paths, while the ass struggles behind with your luggage. The house contains a rather cave-like kitchen downstairs – the other rooms are a wine-press and a wine-storing place and corn bin: upstairs are three bedrooms, and a semi-barn for maize-cobs: beds and bare floor. There is one teaspoon – one saucer – two cups – one plate – two glasses – the whole supply of crockery. Everything must be cooked gipsy-fashion in the chimney over the wood fire. The chickens wander in, the ass is tied to the doorpost and makes his droppings on the doorstep, and brays his head off. The natives are “in costume” – brigands with skin sandals and white swathed strapped legs, women in sort of Swiss bodices and white shirts with full, full sleeves – very handsome – speaking a perfectly unintelligible dialect and no Italian. The village 2 miles away, a sheer scramble – no road whatever – the market at Atina, 5 miles away – perfectly wonderful to look at, costume and colour – no wine hardly – and no woman in the house, we must cook over the gipsy fire and eat our food on our knees in the black kitchen on the settle before the fire.

Withal, the sun shines hot and lovely, but the nights freeze: the mountains round are snowy and very beautiful.

Orazio is a queer creature – so nice, but slow and tentative. I shall have to dart round. We are having a little fireplace in an upstairs room – shall buy grass mats and plates and cups, etc. – and settle in for a bit. But if the weather turns bad, I think we must move on. At the moment a terrible commotion, bagpipes under the window, and a wild howling kind of ballad, utterly unintelligible – Christmas serenade. It happens every day now till Christmas.

I believe you would enjoy it here – but what about the children? They are impossible. There isn’t anything approaching a bath: you’d have to wash them in a big copper boilingpan, in which they cook the pig’s food.

If the weather turns bad, I think we really must go on, to Naples or Capri. Poor Orazio!

Be careful when you travel, of thieves. Be careful even in a sleeping car, of your small luggage. They have opened my bag, and stolen pen, 400 francs and things – also picked my pocket.

Frieda sends love.

THE TALK (supplemented by notes circulated in advance)

Anthony started with the genesis of his novel ‘during a conversation over a boozy lunch in a Rome piazza with a friend of mine and his father, Derek Traversi – an eminent Shakespeare scholar.’ It was Traversi who, in 1971, informed him that Lawrence had stayed at Picinisco; this sent Anthony on a search for Cervi’s villa, which he found, overgrown. Then in the 1990s ‘some shepherds got a state grant to turn it into a B and B … Now it is a kind of Lawrence centre: “Casa Lawrence”’.

About 5 years ago the place recalled him, as it had recalled Cervi from London, and inspired him to his own fiction, just as it had inspired Lawrence to finish The Lost Girl; Anthony’s novel reclaims the real people from the disguises they assume as characters in Lawrence’s. Baynes never visited; but Alvina did, and through her Lawrence imagined the spring in that place that he had never known.

Cervi left Picinisco in 1870 at the age of 16; in 1919 he was 65. It is 750m above sea level, has a castle, and today has a literary festival.

There are still bears and wolves in the surrounding mountains. The area had been well known for brigands, who had opposed Italian unification, as so many in the South of Italy did.

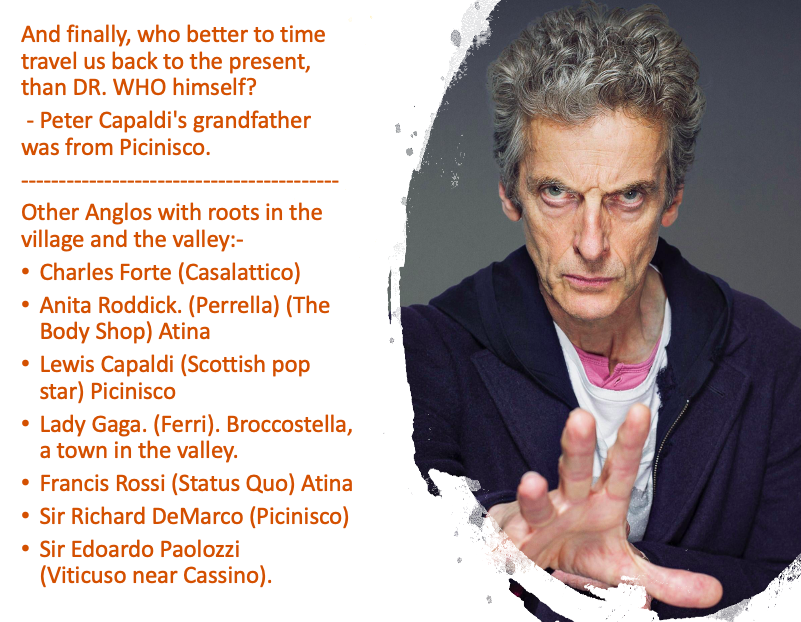

In the last section of his talk Anthony revealed the fact that there was a striking number of people who emigrated from Picinisco to the great art centres of Paris and London, and made livings there as models. Cervi himself was the model for Thornyroft’s The Mower. Another London-dwelling Italian modelled for Eros on Picadilly. Some became artists, and one, Colarossi, opened his own art school in Montparnasse, which was open to women. Anthony intends to publish on this in the future; I’m sure many of those present at the talk will be interested to read/look at this in due course. His concluding slide listed some famous Piciniscans…

Finally, Anthony played a clip of Piciniscan bagpipe players of today…

THE DISCUSSION

Christopher Miles noted that Lawrence’s description of a very rustic dwelling contrasted strikingly to Anthony’s photographs of the exterior of Cervi’s villa. Anthony responded that the grandeur was all exterior; the contrast between outer and inner was respectively that between Cervi’s former glory days and his humble present. Christopher suggested that Lawrence in his descriptions to Rosalind might also have been trying to put her off.

Dudley Nicholas asked about Anthony’s grandparents. He answered that his great grandfather had first left Picinisco in 1870. When his grandfather had left he had stayed on in England, first passing, like all Italian immigrants, ‘through Clerkenwell’, before eventually settling in Newcastle.

Andrew Cooper asked about an Abruzzcan novel which Anthony had mentioned, Giustino Ferri’s 1908 La camminante, which has many plot parallels to The Lost Girl; Anthony did not think that Lawrence had read it, but thought that the two novels were both affected by the same sense of place.

Opinion was divided on the bagpipe players, but great appreciation for In Search of Ancient Gods was expressed. Anthony’s next book will be called Of Lizards and Lovers and Lunch with D.H. Lawrence. He is herewith invited to speak to the Lawrence London Group on it when the right day comes.