D.H. LAWRENCE BIRTHDAY LECTURE 2014

Eastwood, 11th September, 2014

Dr. Catherine Brown

I need to preface this lecture by saying three things:

First, happy birthday, Lawrence.

Second, Lawrence and the First World War is a huge topic. Lawrence didn’t fight in the war, because he was let off on medical grounds; he opposed it, though not on pacifist grounds; and he wrote a lot about it, though often indirectly. So, having been invited to speak about Lawrence and the First World War, I felt the need to narrow the topic, and decided to focus on a collection of poems called All of Us which was published in full for the first time last year, in the 2 volume Cambridge University Press collected Poems of Lawrence, edited by Christopher Pollnitz.

Third, who here has any interest in Egypt whatsoever?

The rest of you, please try to rouse some now.

It will help.

After all, Lawrence was long interested in the country. When he was twenty-three, he wanted to visit it. When he was forty-two (on the far side of the Tutankhamen craze, that tomb having been opened in 1922), he still wanted to visit it. The only thing that put him off going was the expense, and his concern that Cairo in winter might not be good for his ‘damned bronchials’. He wrote to the man inviting him:

I expect Egypt is irritating enough from the modern side. But I’d like to look at the pyramids and to go up the Nile: the old Egypt, spite of tourists, interests me and I’ll have a look at it one day. The very very old world was the best, I believe: before the 4th dynasty.

(Letter to Bonamy Dobrée, Les Diablerets, 24 February 1928, 6L 300)

We’re talking, here, third millennium B.C.

Four months later he wrote the second part of his story ‘The Escaped Cock’, in which a resurrected Jesus wanders into Sinai and has an affair with a Priestess of Isis, who had previously had both Caesar and Anthony as lovers. After them she had turned away from Roman modernity back to Osiris and the ‘very very old world’ which Lawrence, who had read many ‘fat books’ on the subject, thought ‘the best’.

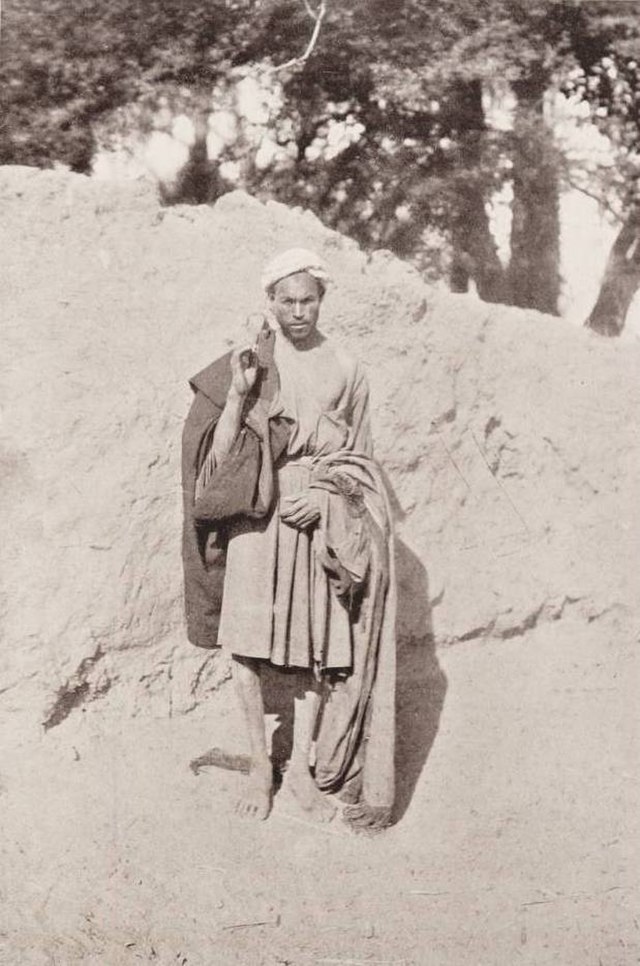

Fast forward nineteen hundred years to about 1900, and we’re in the modern Egypt in which Lawrence isn’t interested. The descendants of the Coptic-speakers now speak mainly Arabic. Most of them worship neither Isis nor her imagined lover Christ, but Allah. The Temples of Isis are abandoned. Or rather, they’re being excavated.

Temple of Isis, Egpyt, around 1900

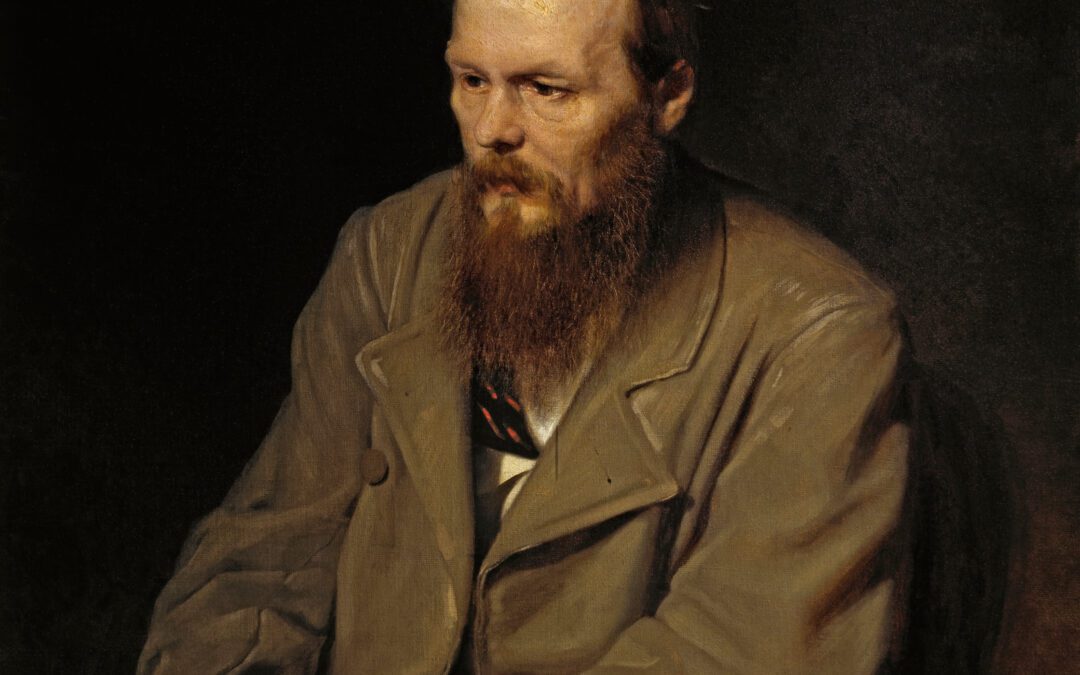

Egpytian archaeological dig, late nineteenth century

Nominally, the country is Ottoman, but it has been a British protectorate for twenty years, the British having successfully scrambled for it, narrowly beating the French. The Germans hadn’t managed to get anywhere in the North African sun – the closest they had was Tanganyika, in middle East Africa – but they were on good terms with the Ottomans.

In the meantime, the ruins of the old old world, like the territory of the modern, was divided between the European powers. Egypt’s archeological sites were shared out between the British, the French, the Germans, the Italians, and the Americans.

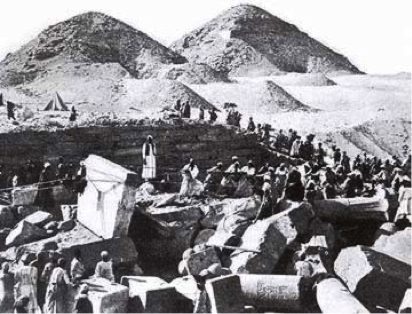

U.S. marines and the Great Sphynx, c. 1900

For the most part they got on perfectly well. But there were a few tensions. Some of the archeologists doubled as spies. The most famous was T.E. Lawrence, an archaeologist-spy who kept an eye on the Berlin to Baghdad railway, which the Germans were building to strengthen their relations with the Ottomans. In Egypt, David George Hogarth was in charge of surveying Ottoman installations as well as Egyptian ruins, and it’s likely that some German archaeologists were spying on British installations.

After all, the anti-German Entente Cordiale between Britain and France was only a few years away, in 1904 – and when war came ten years later, Egypt became the main base from which Britain attacked the Ottoman forces, which were in part commanded by German officers. The Sinai temples of Isis were surrounded by the dismembered bodies not of Osiris, but of English and German soldiers.

But around 1900 there was at least one archeologist in Egypt who I am pretty certain was no kind of spy. His name was Heinrich Schäfer, and he was working on a German dig for the Berlin Museum.

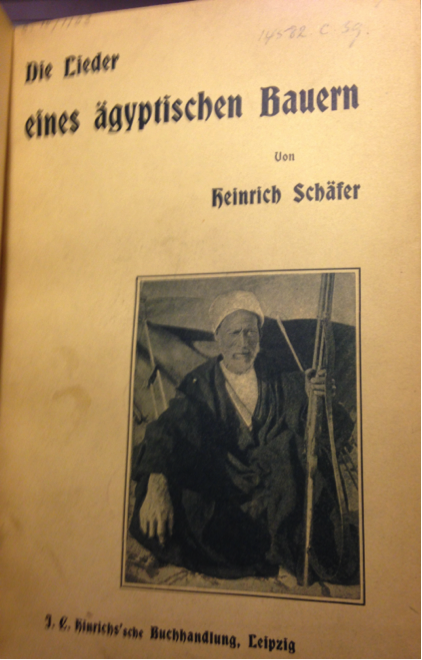

Unlike the young Lawrence, he was not only interested in the old world. Though he was an Egyptologist, not an Arabist, he learned enough Arabic to take an interest in the fellaheen (or peasant) labourers on his dig, and in their folk songs. Two of the farmers would recite their songs for him, he transcribed them using Roman script, and, with some help from an Arabist friend, translated them into German. In 1903 in Leipzig he published 134 of them in a parallel text edition: Die Lieder eines agyptischen Bauern, von Heinrich Schäfer. ‘The songs of a few Egyptian farmers, from Heinrich Schäfer’.

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

This book is an extraordinary act of cultural translation. He was giving an illiterate culture written form in the Roman script. He was translating Islamic sentiment into a Christian language; ‘Allah’, in his translation, becomes ‘Gott’. He tries to mediate the effect of his cultural translation with his accompanying notes, explaining some specifics of Egyptian culture.

But his introduction makes it very clear that he is not offering these songs principally to academics, but as literature, concerned with much the same things – work, God, love, prison, death – as literature anywhere. He explicitly offers the songs in order to make connections between people of different places.

In any case, he was writing down songs which were being sung in the present, and since the Nile Delta at that present was full of Europeans, it is not surprising that they to some degree reflect a reality in which Egyptians and Europeans share. The work songs, for example, which complain about the harshness of the overseers, would at that time have been sung as complaints about their work on the digs, as Schäfer, in his sensitive notes, shows himself to be keenly aware.

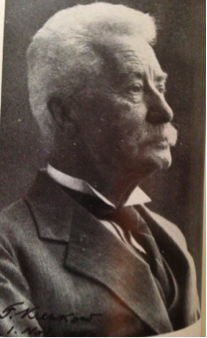

But not all Orientalists worked on-site, compelling the descendants of the people they were researching to literally do their spade-work for them. Many were Europe-based scholars, including many amateurs. One, a certain Fritz Krenkow, was a compatriot of Schäfer’s, but had lived in England since 1894 when he was 22. Two years later he married an Ada Beardsall, and thus he became the uncle of the eleven-year-old DH Lawrence.

Fritz Krenkow, 1949 D.H. Lawrence, c. 1895

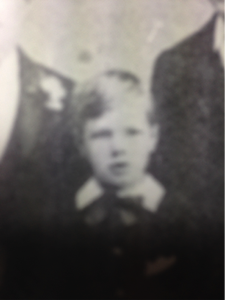

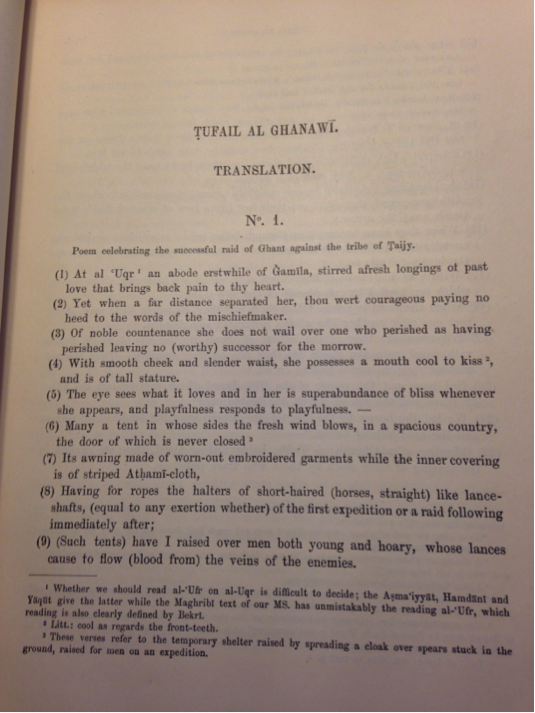

Though his job was in a Leicester hosiery firm, Lawrence remembers that he was ‘always working away at his Arabic’ (1L 77). He published in Orientalist journals in both German and English. Lawrence first started thinking about visiting Egypt soon after Krenkow had finished his edition and translation of the poems of Tufail Ibn Aug al-Ghanawi (pronounced Tufel Ibne Org al-Ganavi) and At Tirimmah Ibn Hakin At-Ta’yi (pronounced At Tirima ibne hakin at taye).

Krenkow Poems, 1927

These poems are very different to Schäfer’s Lieder, quite apart from being in his adopted English rather than his native German. They are literary poems, not folk songs; they are of the Arabian peninsula, not Egypt; and they are ancient not modern, being pre-Islamic. But still – these translations are an attempt, on the part of an Anglo-German, to build a bridge between cultures, and increase knowledge about a part of the world which was an increasing site of European tensions.

One of Tufel’s long poems is about a raid:

We slew as required for our slain an equal number (of them) and (carried away) an uncountable number of fettered prisoners.

We quench (the thirst of blood of) the blades of the Mashrafi-swords with their (blood) (5)

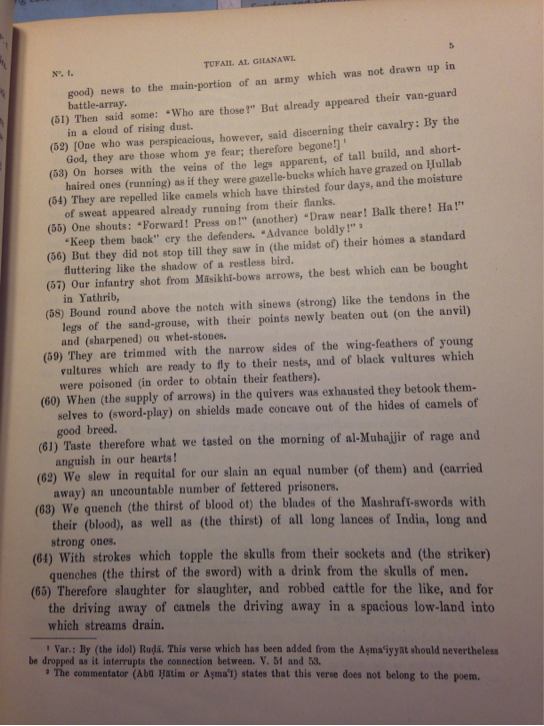

These ancient texts, which still existed in the Arabian peninsula at the time of the First World War, would have acquired a new resonance then.

Krenkow Poems, 1927

Krenkow Poems, 1927

Back in 1910, Krenkow may well have given his nephew these translations to read – and not only his own, but Schäfer’s. He certainly got the latter from somewhere, because he translated several of the love poems for his then-fiancée Louie Burrows. He might have liked their brevity and folksy directness, retained in Schäfer’s German, more than the longer, more literary poems which his uncle had rendered into stilted English.

Where Schäfer had bridged a big cultural gap, Lawrence was bridging another, smaller one, from German to English. He was keen on improving his Nottingham High School German, and he seems not to have known about, and therefore cribbed from, Frances Breasted’s 1904 English translation of the songs.

But he wasn’t in any case interested in giving Louie the most direct translation possible. He was giving her love poems, and stepped up the sex, as one might expect – which would only have been to return them closer to their original Arabic state, which Schäfer confesses that he felt obliged to censor in about 12 cases (xi).

In giving them to her, Lawrence pretended to Louie that the German translation he was working from was by his uncle, not Schäfer. If this was trying to impress, it was probably not only in relation to his Uncle’s Arabic skills, but in relation to his simply being German. Think of The Rainbow – how glamorous and cultured to the intellectually-hungry it is to be ‘foreign’, in the environs of Eastwood in the nineteen-teens.

Two years later Lawrence dramatically widened the circle of his own life by eloping with a German, and two years after that, marrying her – just three weeks before his country declared war on hers. Frieda was not only German but of a military family; her father was a reserve officer in the garrison town of Metz, tensely occupied by Germany since the Franco-Prussian war in which he had suffered a shelling wound to his hand; her cousin was a man Lawrence referred to, five months after his death in 1918, as ‘that Richthofen flying-man’ – known to England as the Red Baron (3L 282).

With the beginning of the war, many things became more difficult for the newly-weds, including, as it were, Anglo-German intercourse. Frieda had to correspond with her family via Switzerland, and could no longer receive money from them.

When the war was only a few days old the Lawrences were questioned by three sets of detectives after they were overheard speaking German at a dinner party. In May 1915, after the sinking of the Lusitania, East End shops thought to be German-owned were smashed up. They moved to Cornwall, where they defiantly sang ‘one German folk song after another’ (Kangaroo 223).

Frieda wasn’t interned, as many Germans were, because she was naturalised; she had after all been previously married to another Englishman – but she and they were closely watched, culminating in their expulsion from Cornwall, where they were suspected of trying to assist German U-boats.

Her uncle-in-law Krenkow, also naturalised, wasn’t interned either – but he too had a rough war. In his introduction to his volume of Arabic poems, explaining why it had taken them so long to get into print – this was in 1927 – he wrote:

When the whole text and the translation had been printed and the Apparatus was in hand the great war broke out and the introduction which I had written was lost, probably through the kind assistance of the Censor.

The following words barely conceal a world of troubles:

The war brought me quite different cares than the edition of this work which had to be laid aside. Fortune was not favourable […] and for some years I had not even the books of my own library at hand (xi).

1916 was for Lawrence the turning point in the war, with the resignation of the more moderate Asquith, and his replacement by the more bellicose Lloyd George. After all, Asquith had visited Lady Ottoline Morrell’s Garsington, a centre of pacifism with which Lawrence was connected, even though it was opposed to his own war policies.

In Kangaroo, the autobiographical Somers recalls:

From 1916 to 1919 a wave of criminal lust rose and possessed England, there was a reign of Terror, under a set of indecent bullies like Bottomley of John Bull and other bottom-dog members of the House of Commons (212).

In the winter of that year, at the time of the resignation of Asquith, Lawrence chose to revisit the Ägyptische Lieder – to revise the translations he’d already done, and to make many more. He called this collection of 31 poems All of Us. By this time his German was much more fluent, and in sofar as they are translations, they are better.

But why did he choose to translate those poems then? Were they perhaps attractive to him because he was taking something German, and assimilating it into his very language – making the two tongues as intimate as they could be? Their offspring, his slightly archaic translationese, unEnglished his own language, as Lawrence himself was unEnglished when he first visited Germany with Frieda in 1912.

He even asked the daughter-in-law of the six-days resigned Prime Minister, his friend Cynthia Asquith, whether he might inscribe the poems ‘“To Cynthia Asquith” – damn initials’ (3L 49) – to which she assented, even though her husband had just had three teeth knocked out in the war, as Lawrence had fictionalised his story ‘The Thimble’. Two years later, she even bicycled her copy across London to a potential publisher, Beaumont, for consideration (Poems II, 698).

But if the desire to bring England and Germany together, under the neutral auspices of a non-European culture, was part of his motivation, then making this public certainly wasn’t.

He told neither Cynthia nor Beaumont nor his agent Pinker that these poems were translations from the German, let alone previously the Arabic. For decades after his death, they were assumed to be Lawrence’s originals. So far from boasting of any German uncle, he cut out their Germanness altogether.

There are several possible explanations for this. But one is his recognition that it would not help their chances of publication to present them as translated from German. This was, after all, almost the point in the war when the British royal family translated its own name as Windsor, and denied its original, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

And he needed money. In the previous year, 1915, his magnum opus The Rainbow had been published but suppressed within six weeks, officially on grounds of obscenity – but it was also seen as inappropriate for wartime: a review in The Star stated ‘The wind of war is sweeping over our life…A thing like The Rainbow has no right to exist in the wind of war’ (The Rainbow xlvi).

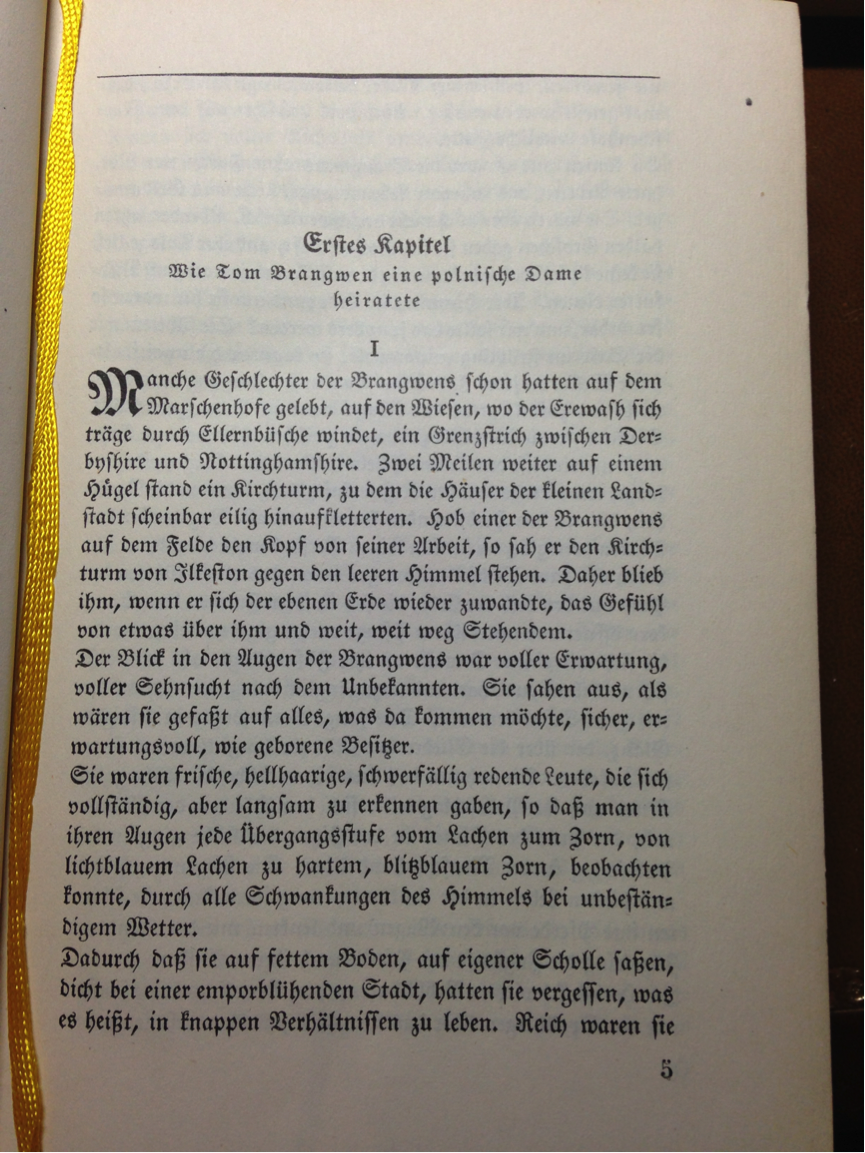

The English Will Brangwen and his quarter-German, three-quarters Polish wife, for some reason give their children almost ostentatiously German names: Ursula, as it would be in Germany, and Gudrun. Gudrun had already existed in the first version of The Rainbow, from spring 1913. But it was only after the war had started, around November 1914, that Lawrence translated Ella into Ursula. The motivation is more understandably Lawrence’s than of her parents.

He had also specified to his agent Pinker:

I want on the fly leaf, in German characters, the inscription

‘Zu Else’ – i.e. ‘zu Else’ [his handwritten impression of

Gothic script]. Put that in for me will you? It is just

‘To Else’. But it must be in Gothic letters. We shall have

peace by the time this book is published.

(31st May 1915, Greatham, 2L 349)

He was by now perfectly familiar with Gothic letters; for one thing, the Schäfer poems are printed in them.

In his pre-war story ‘The Mortal Coil’, based on a tragic incident in the life of his father-in-law-to-be, a German woman sits waiting for her German officer lover,

writing her name in stiff Gothic characters, time after time:

Marta Hohenest

Marta Hohenest

Marta Hohenest (England, My England 172)

(Leading Lawrencian scholar John Worthen informs me from his textual work on the play David that Frieda used to do precisely this; thanks to him for this insight!)

In ‘The Captain’s Doll’, of 1921, the Countess Johanna zu Rassentlow, whose lover in this post-war world is a Scottish officer occupying the Rhine, also sits and:

writes her name in stiff Gothic characters ‘Johanna zu Rassentlow’ – time after time, ‘and then once, bitterly, curiously, with a curious sharpening of her nose: ‘Alexander Hepburn.’ (The Ladybird, The Fox, and The Captain’s Doll, 78)

She, thus, is translating her supposed ‘enemy’ lover into her own font. Lawrence wished to make a similar gesture in his dedication of The Rainbow to a woman who had been taught by Max Weber, was the German pacifist-equivalent of Bertrand Russell, who was married to a man who in 1917 would make public peace proposals, and who herself would later translate Lawrence’s story about a returned English soldier, ‘The Fox’, as ‘Der Fuchs’.

In the Methuen edition of September 1915, the dedication was included, but not the Gothic characters.

It is a poignant postscript to this story that the first German translation of the novel, published in Leipzig in 1922 in the inflationary Germany depicted in ‘The Captain’s Doll’, when it probably cost about a million marks, although it omits the dedication altogether, it is in its entirety in the Gothic script.

First edition of the first German translation of The Rainbow, trans. F. Franzius, 1922

It begins thus:

First edition of the first German translation of The Rainbow, trans. F. Franzius, 1922

Given that up to one thousand and eleven copies of this book, with its ‘Zu Else’ dedication, were burned – which is why first editions of the novel are so expensive – it is not surprising that the cash-poor Lawrence treaded carefully when it came to revealing the origin of his poems which are, after all, mainly concerned with the war – and not in a way which incites Tommies to kill more Fritzs. Fritz was after all, his uncle’s name. He wrote to Pinker, with heavy irony: ‘Give it the people as the “war literature” they are looking for: they will find themselves in it’ (3L 51).

Of the 31 of Schäfer’s 134 poems which Lawrence translated, only one is possibly set at a time of war. A young woman is imagining the distant tent in which her lover is lying; the poem ends: ‘Dein Schwert ist aus Silber and glänzt auf dem Diwan’ – ‘your sword is of silver and gleams on the divan’ (Poems II 916). Lawrence glosses his own poem ‘A young woman muses on her betrothed, who is in Mesopotamia’; and he translates the sword into a first world war ‘bayonet’ (Poems I 139).

But this is a relatively easy translation, from sword to bayonet; the Nile to the Euphrates. A greater leap is made in the 23 other of Lawrence’s translations which in the original and Schäfer have nothing to do with war, but in which at the very least, as Lawrence put it in the Foreword to Women in Love, ‘the bitterness of war may be taken for granted’ (485).

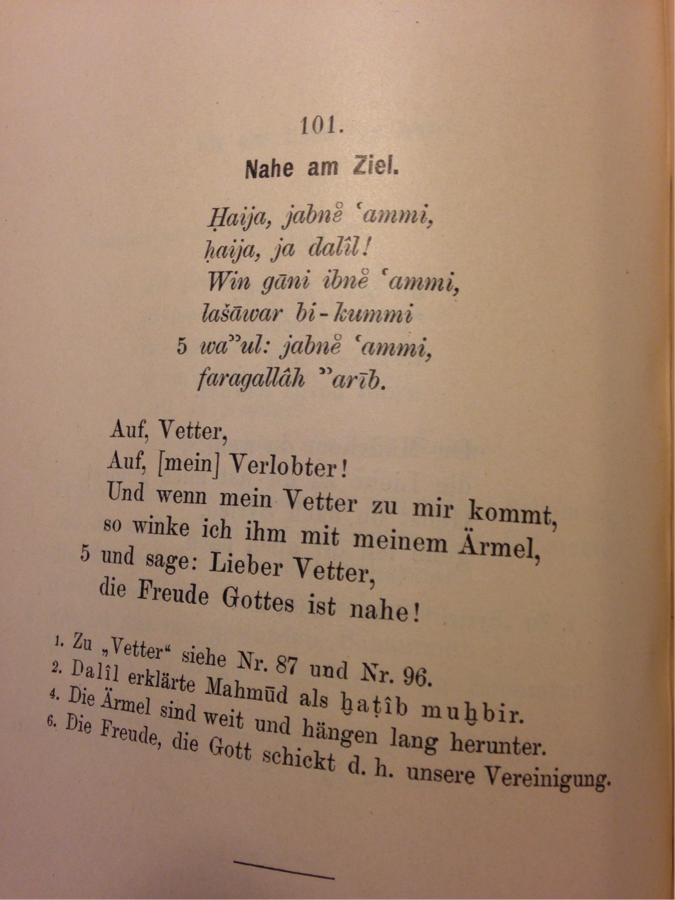

Sometimes, though, the war is unmistakably present. An example is the translation of Schäfer’s ‘Nahe am Ziel’, ‘Close to the Goal’:

‘Auf, Vetter,

Auf, mein Verlobter’

Und wenn mein Vetter zu mir kommt

So winke ich ihm mit meinem Ärmel,

Und sage: ‘Lieber Vetter,

Die Freude Gottes ist nahe!’ (Poems II 917)

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

‘Up, my relative

Up, my fiancé!’

And when my relative comes to me

I wave at him with my sleeve

And say: ‘dear relative,

God-given joy is close!’

Far from sunny Egypt – in Cornwall in the winter of 1916, at the end of a year in which Percival Lucas, the model for Evelyn in ‘England, My England’, and – to be written in the future – Lady Daphne’s brother in ‘The Ladybird’, and Herbert Chatterley, brother of Clifford Chatterley, are all killed on the Western front – this became:

Near the Mark

(A timid girl sighs her unconfessed love for the man in Flanders)

Ah my love, my dear!

But what if my love should chance to hear

As he is passing where the shells are thrown?

What if he stopped and turned to me here!

I should lean and whisper in his ear:

‘My love, my love, now all is known,

God in His gladness has drawn so near,

You, God and I are alone.’ (Poems I 140)

A war poem in the sense of Siegfried Sassoon or Wilfred Owen this is not. It is not merely of its time and place. It cooperates with the spirit of its Arabic original, which Lawrence – and I – have never read, to transcend the parochialism of a nationalist war.

Indeed, 12 of the poems, including 8 ‘war’ poems, are not geographically translated from their original setting at all. That is, they are set in Egypt – or as well there as anywhere in the Maghreb, so universal are the situations being described. Possibly due to the choices of the two farmers who recited to Schäfer, or his own editorial choices, this is not folk literature like Lawrence’s dialect poems, redolent of provincial specificity. And so it becomes habitable by Lawrence, with his particular needs, in the time of war.

He makes the war inflection, often by conscripting one of the protagonists as a soldier. In his translation of a Schäfer poem in which a boy addresses his older brother, Lawrence adds the note ‘A child speaks to his brother, who is a soldier’ (Poems I 141). To Schäfer’s ‘Schaukellied’, Lawrence’s ‘Swing Song’, is added the specification that a soldier is swinging his love (Poems I 149). In ‘Forlorn’, the woman’s handkerchief waved coquettishly in ‘Verliebt’ becomes a symbol of mourning (Poems I 147).

Yet Lawrence’s wartime needs were not on behalf of the English. Though he disapproved of Frieda supporting the Germans, and in one moment of rage during the war he said that he wanted to kill a million or two Germans, more consistently he didn’t want to kill a single one. And so it is appropriate, that whilst he inflects these Egyptian poems by war, he holds many of them open, with regard to which side is concerned.

In the poem about the brothers the older one could be an Egyptian soldier, let’s say, fighting the English in the uprising of 1882. Or, indeed, a German one. Of course, the poem is in English. When one reads the word ‘Colonel’ in an English poem one mentally pronounces it as such, not ‘Kolonel’. But Lawrence has already demonstrated how easy the transition between German and English is. Translated back into German, many of his poems would work just as well for German soldiers.

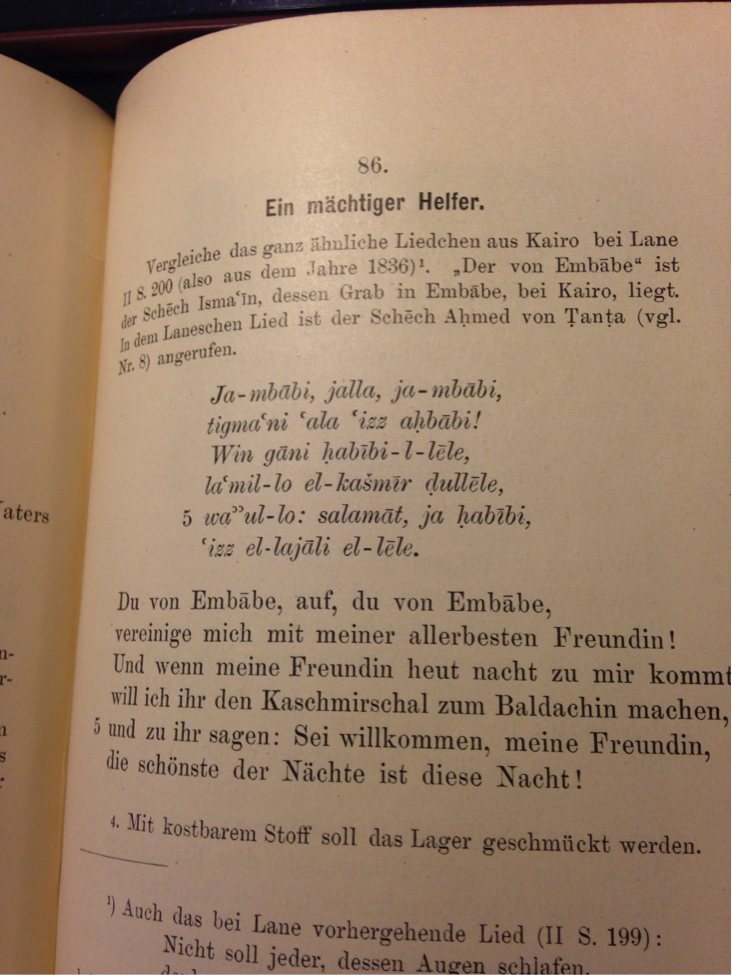

Of the poems which retain their original setting, none is so poignant by this virtue as ‘A Powerful Ally’, which translates Schäfer’s ‘Ein mächtiger Helfer’, Schäfer starts:

‘Du von Embäbe, auf, du von Embäbe,

vereinige mich mit meiner allerbesten Freundin’

(Poems II 927)

‘You from Embabe, up, you from Embabe

Unite me with my very best female friend’

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

Lawrence reverses the genders, and has ‘A young lady speak[s] to the Colonel of her lover’s regiment’:

‘Oh Colonel, you from Embaba,

Join me to my well-beloved friend.’ (Poems I 144)

The ‘you from Embaba’ is in the Arabic a Muslim Saint; he too is conscripted, as a Colonel. Embaba is on the Nile’s West bank just three miles from the Dobrée’s home where twelve years later, Lawrence nearly found himself. In 1916 it was a centre of military training and intelligence gathering. It seems that a local woman has found a soldier lover. Here, more than in any of the other poems, the disjunction between the poem’s origin in a relatively pacific Egypt, and modern militarised Egypt, is made palpable – though only to those, such as Lawrence and us, who know about the originals.

Seven of the poems are geographically transposed but within Africa or the Middle East. In these cases the transposition is pointed with regard to the War, but again, only two definitely concern an English soldier.

One of these is ‘Too Late’, a translation of ‘Der Nachzügler’, in which a straggler pilgrim explains that his country, and his goal, is Mecca.

In ‘Too Late’ a straggler in Mesopotamia exclaims:

‘Alas, my land is England, here I know not how or whence

I come, nor what is my goal.’ (Poems I 148)

Mesopotamia, shortly to be renamed Iraq, was invaded by the British in 1914, in a manoevre which ended in disaster by 1916, half a year before Lawrence wrote his poem. The soldier is English, but ‘alas’ that he is so; and he knows not why he is there, nor what his goal is.

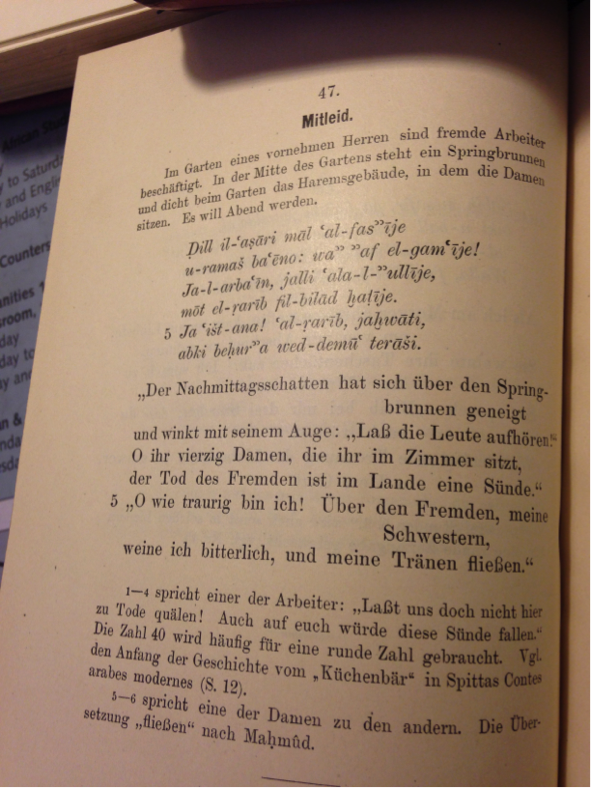

In Schäfer’s ‘Mitleid’, ‘Compassion’, a forced labourer in a foreign land begs for rest, and one of forty women in a room (which Schäfer glosses as a harem) sees him and weeps for him (Poems II 936).

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

In Lawrence’s ‘Antiphony’ ‘A British sailor, prisoner of war, works in a garden in Turkey’ (Poems I 149). In March 1915 the British navy had unsuccessfully stormed the Dardanelles and was shelled by the Turks. Here a Turkish woman takes pity on him.

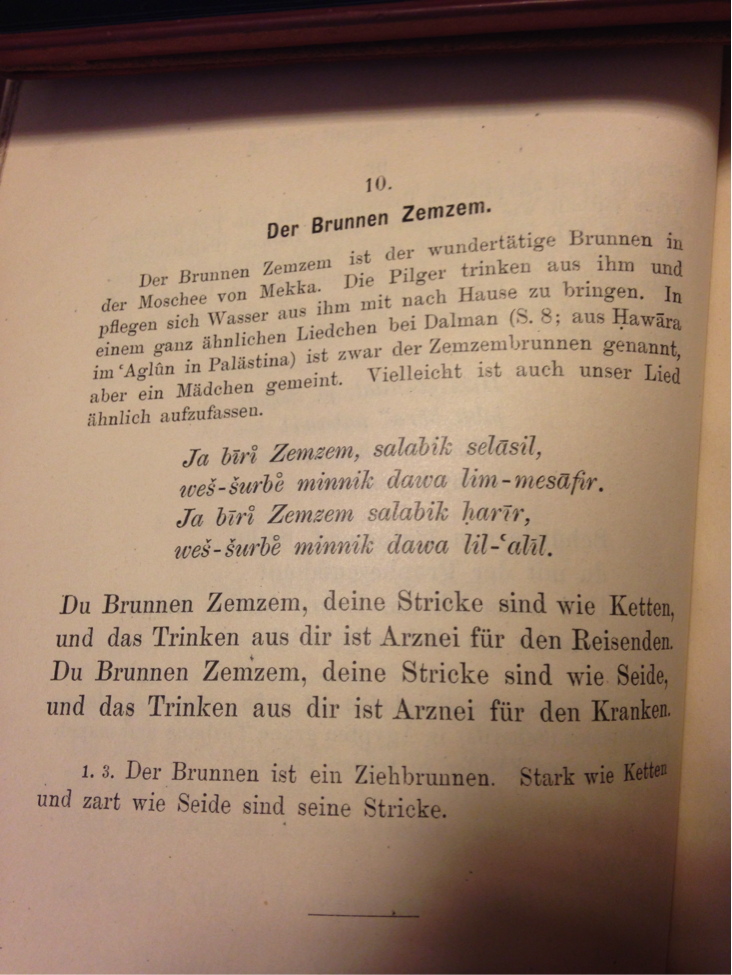

In the other translocated Middle Eastern poems an English or German soldier could equally be concerned. ‘The Well of Kilossa’ is based on ‘Du Brunnen Zemzem’ – a song of grateful praise to the health-giving well.

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

Zemzem, as Schäfer tells us, is the well at Mecca. Kilossa is in Tanganyika or ‘Deutsch Ostafrika’, the German colony which the British Imperial Forces entered in August 1916. There was no decisive victory. The ‘thirsty soldier in East Africa’ of Lawrence’s note could be German or English; both would have been much in need of the well (Poems I 140).

Had he kept the setting at the well of Kilossa, neither soldier could have been present, being Kafirs; but that well was firmly under the English influence, Mecca being the base of T.E. Lawrence’s Arab revolt.

Eight poems, though, are moved to Christendom: one from a dig to a munitions factory, which, if not definitely European, is more likely to be that than Egyptian; one to Greek Salonika, one to Flanders, one through translating a mosque into a ‘cathedral church’, one through translating a hymn of praise of the Prophet into a father’s benediction of his son in the name of Jesus, and two by translating the Prophet and the Muslim Saint Seijid respectively into grey nurses, who in the second case are ‘Sisters’ with a capital ‘S’.

Salonika is the Greek port where the British landed in October 1915; Henry in ‘The Fox’ serves there. But since the Germans bombed the British there, it too could concern a German. The translations into an explicitly Christian setting are more striking, because they are not convincingly Christian. By contrast, Schäfer’s ‘Preis des Propheten’ reads as too Christian for a translation of a hymn of praise to the Prophet. It uses the words and syntax of a German liturgy: ‘der Segen Gottes werde zu Teil dem Propheten’ (Poems II 922).

Lawrence’s ‘Benediction’ despite replacing camels by cattle, and a palm by a willow, reads strongly as a translation of a poem from another culture:

The willow tree leans and sweeps her leaves like a dress,

The cattle run anxious in quest as the time draws nigh;

And stones shall be soft to thy foot, become pleasant to press,

The pebbles in God’s name praise thee for comeliness

Seeing God alight in thy face, child dear to mine eye.

(Poems I 142)

That other culture could of course be the Hebraic, from almost the same part of the Middle East; and so here Lawrence’s saturation in the English translation of Old Testament Hebrew, and his exposure to a German translation of an Arab Islamic hymn, dovetail and join. In his strangely foreign cadences he has not brought a truce not only to the Anglo-German war, but to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which was just at this time coming into existence.

In ‘Straying Thoughts’, the mosque of ‘Schlechte Andacht’ becomes a ‘cathedral church’ where there are ‘grey doves in the holy court/ Feeding on pure white sugar’ (Poems I 141). This too sounds odd. The phrase ‘the cathedral church’ is either a technical term on the part of someone who really knows their Anglican terminology, and that the term ‘cathedral’ is short for this phrase – or the opposite, the phrase, possibly, of a foreigner to Christianity. Do cathedrals have ‘holy courts’? Is this not more mosque-like? When did you last see doves eating sugar in a cathedral church court? Again, the cultural specificity of Christianity is broken open.

On the other hand, the ‘holy sister’ in the poem ‘The Saint’ is, by virtue of being definitely Catholic, more likely to be German than English (Poems I 143). ‘God’, in Lawrence’s poems, is rarely allowed to be definitely on the English side – tugged as God, or ‘Gott’ was, during the war, between the prayers enlisting his support raised from German churches, and English churches.

That is if we read this poem on its own. Read in the sequence that is All of Us, it appears soon after ‘Supplication’, in which ‘A young lieutentant, who joined the Roman Catholic church whilst at Oxford, prays on the battle-field’ (Poems I 142). ‘The Saint’ too could be his prayer. ‘Supplication’ is a prayer of simple faith, ventriloquised by Lawrence seriously, without comment. The mention of Oxford creates in the reader’s mind the tie to the soldier’s home of which he himself would have been acutely conscious whilst on the field. If he dies, one feels, there will be a corner of a foreign field that is forever Oxford.

But this is the only poem, even of the five which have an English setting or reference, which has this national simplicity – and this is significantly the small-c catholic prayer of a large-C Catholic, calling for God’s will to be done.

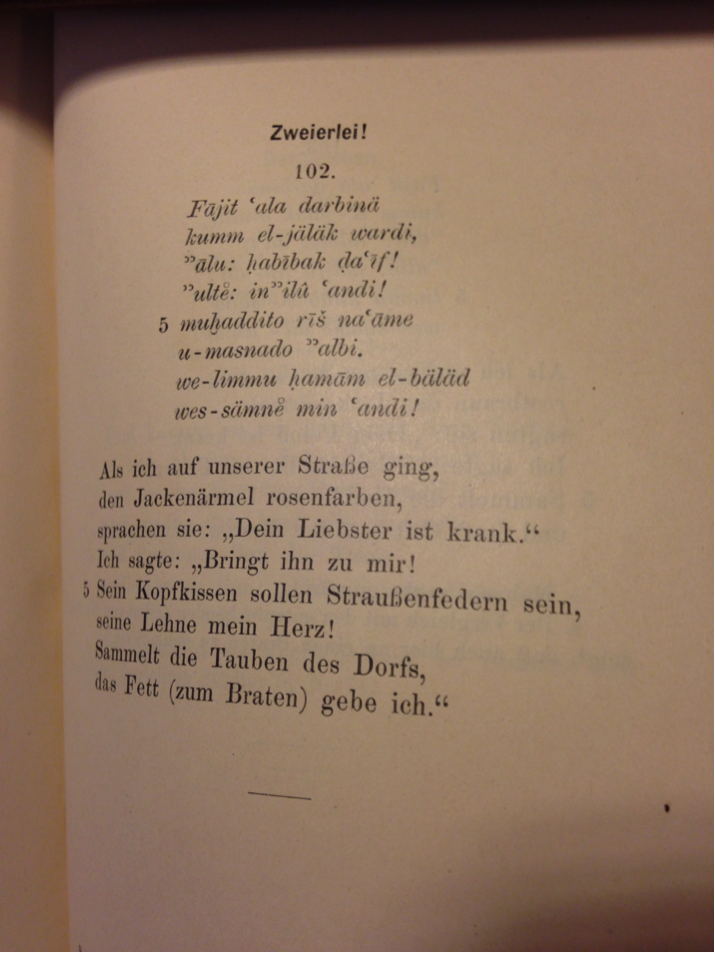

The others English poems reference St Paul’s, Salisbury Plain, the East End, but not straightforwardly. In ‘Twofold’, a woman, as in the original, hears that her lover is wounded and orders him to be brought to her for her to nurse. In the original she orders the doves of the village to be gathered for a sacrifice.

Schäfer Lieder, 1903

In ‘Twofold’ this becomes:

And you, Oh see the myriad doves that walk

Beneath the steps of St Paul’s: catch several,

Go quickly now, let nobody stand and talk,

One of you kindle a fire to consume them withal.

(Poems I 141)

Here a symbol of England and of English Christianity is dislocated by relation to Islamic ritual; we are here, as the scholars David Cram and Christopher Pollnitz note, in the modernist fragmented world of ‘The Waste Land’ (142). England has been spiritually ruptured by war, and now lets other cultures in.

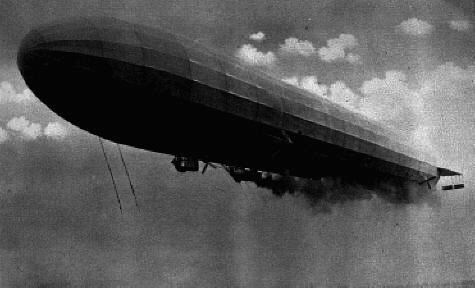

It was of course also physically ruptured. ‘Night-Fall in the Suburbs’, of which in the original is a child’s call to other children to come in at night, remains that, but in the context of a Zeppelin raid:

There’s the Zeppelins coming

Overhead;

I can hear them humming.

You’ll look well when you’re dead.

To this is added a sinister rendering of a chant which Lawrence would have known from his childhood:

My coffin shall be black,

Six angels at my back,

Two to watch and two to pray

And two to carry my soul away. (Poems I 146)

From January 1915 there were Zeppelin raids over England, which Lawrence witnessed from his house in the Vale of Health, Hampstead Heath. On the 8th September 22 people were killed.

A Zeppelin

It is possible that Frieda commented as her avatar Harriett does in Kangaroo:

‘Think, some of the boys I played with when I was a child are probably in it’ And he [her Lawrencian husband Somers] looked up at the far, luminous thing, like a moon. Were there men in it? Just men, with two vulnerable legs and warm mouths. The imagination could not go so far. (216)

Somers’s couldn’t; Lawrence’s could, and ours do perforce.

Lawrence described the September raid in a letter, which was used as a source by Tennessee Williams in his play about Lawrence, Frieda, and their friends Mansfield and Murry on this night, which he moves to Christmas 1915. This play has only just been discovered by the scholar Gerri Kimber, and its first act is called ‘The Night of the Zeppelin’.

In his letter to the pacifist Ottoline Morrell Lawrence wrote:

It was like Milton – then there was war in heaven. But it was not angels. It was that small golden Zeppelin, like a long oval world, high up. It seemed as if the cosmic order were gone, as if there had come a new order, a new heavens above us […] I cannot get over it, that the moon is not Queen of the sky by night, and the stars the lesser lights. It seems the Zeppelin is in the zenith of the night, golden like a moon, having taken control of the sky; and the bursting shells are the lesser lights. So it seems our cosmos is burst. (2L 390)

Williams’s stage direction is:

THE SKY THROUGH THE WINDOW IS CRISS CROSSED BY SILVER BEAMS. INTO THE LIGHTED AREA SAILS SERENELY THE CURIOUS SILVER OVAL OF THE ZEPPELIN.

His stage direction at the end of the act is:

FROM THE STREET COMES THE PURE SINGING OF A BOY’S CHOIR –

‘God rest ye, merry gentlemen, May nothing ye dismay –’

CURTAIN. (Kimber 2014)

– which echoes the childs’ sinister play. Neither the Lawrence we know from his own writing, nor from that of his disciple Williams, suggests that he perceived this raid in terms of Anglo-German emnity; the very fact of the war is changing the composition of the heavens, in a way which far transcends nationality.

During the war, despite the best efforts of Cynthia Asquith, the poems of All of Us did not get published; they were too open. So far from being from sung in public, like the fellaheen songs, they weren’t even read in private.

Only in July 1919 did twelve of the poems, rewritten and rearranged into the collection Bits, get selected by the American journal Poetry, and published under the title War Films. The title was not apt. Documentary films of the war were shown during it, but Lawrence, who did not go near a battlefront except in imagination, could not write their poetic equivalent. They are lyric, not filmic in quality, and have an archaic, not high-tech, feel, as befits their translation of an oral culture. Their new titles make the British war far more explicit: ‘Star Sentinel’ becomes ‘Mother’s Son in Salonika’; ‘An Elexir’ becomes ‘The Jewess and the VC’; ‘Night-Fall in the Suburbs’ becomes the Tennessee Williamsesque ‘Zeppelin Nights’ (Poems II 914-15). And so on. As the inclusivity of All of Us was replaced by the fragmentation of Bits, the poems were narrowed slightly.

But their openness, which has been my subject, is interesting in the context of Lawrence’s very considerable interest in the idea that mankind is divided into different peoples. He often sounds essentialist on this point.

In Fantasia of the Unconscious he gives his own version of the Babel myth. Mankind was originally one; then the glaciers melted and there was a world flood, producing different races, peoples, nations. Even before the war, he had started conceiving peoples in opposed pairs: the German and the Italian, or the German and the English, which he characterised as militarist and commercialist respectively.

In his pre-war essays about Germany he castigates its militarism, and in Metz he sides with the disgruntled French – though he did know about the other Germany, whose culture he had been reading for years – that of the Dresden where the Chatterley girls are sent for – in a charming expression ‘music among other things’ (Lady Chatterley’s Lover 6).

In his 1916 essay ‘The Crucifix Across the Mountains’ he speculates:

Maybe a certain Grössenwahn [megalomania] is inherent in the German nature. If only nations would realize that they have certain natural characteristics, if only they could understand and agree to each other’s particular nature, how much simpler it would all be. (Twilight in Italy 91)

So he writes in his so-called ‘non-fiction’. But his national theories do not translate into the war poetry. So how does it fare in his war fiction? I am not including here Women in Love, in which the war is only implicit.

His just-pre-war story ‘The Prussian Officer’ has a title which clearly stresses a national group. To be Prussian, to the English mind in 1914 when it was published, is as good as to be an Officer. But significantly Lawrence didn’t want that title. It was forced on him by his publisher, who also made it the title of a whole collection; he had wanted the perfectly English sounding ‘Honour and Arms’. Lawrence said: ‘Garnett was a devil to call my book of stories The Prussian Officer – what Prussian Officer?’ (2L 241).

And indeed, the story has some of the vagueness of geographical context of some of the poems in All of Us. We are told that the officer ‘was a Prussian aristocrat, haughty and overbearing. But his mother had been a Polish Countess’ (Prussian Officer 2). Even here, as in The Rainbow, the Austro-Prussian-Russian Poland comes leaping in to disrupt national purity. Thereafter the officer is referred to as the officer, his orderly as the orderly. Only once again is he ‘the Prussian’ (3). There is a plain, presumably the Bavarian plain (for those who know their military matters, the uniforms are Bavarian), and there are mountains, and these are presumably the Alps. But none of these are named; the story is of a struggle between two men, and one of these men’s consummation in the abstract mountain peaks. Lawrence was largely justified in asking: ‘What Prussian officer?’.

Admittedly, his other two pre-war German military stories are more precisely German. ‘The Thorn in the Flesh’ about military training in Metz, and ‘The Mortal Coil’, set, I think, in Munich, is full of German names, titles, architecture, and currency. At one point, all the lover’s ‘German worship for his old, proud family rose up in her’ (England, My England 175). Yet this is a rare description, for these stories, of a character’s sentiment in terms of national character.

In the English war stories ‘The Thimble’, 1915, ‘The Blind Man’ and ‘The Fox’, 1918, and ‘The Wintry Peacock’, 1919, there is no national specificity, and no feelings of enmity towards Germans, despite the fact that the characters have suffered in the war.

In the war-aftermath story ‘The Captain’s Doll’ of 1921, much German is spoken; it opens with a German conversation between friends, and this is a respectful gesture of linguistic hospitality, in a story which observes defeated Germany and Austria, as Lawrence did when he visited them in 1921, entirely without triumphalism. We have a German countess in a relationship with a Scots officer, but this is no metaphor; Germany raped by the occupier, or indeed united with the enemy, in defiance of that enemy’s ordinance against fraternisation. Hannele and Hepburn, like Frieda and Lawrence, are not Romeo and Juliet – representatives of rival houses – but two, fractious individuals, to whose relationship the contexts of their warring nationalities is not significant.

The one strongly national title which was of Lawrence’s choosing was of course ‘England, My England’, written in June 1915 – and that is about an Englishman who goes to war for the sake of war itself, not of killing Germans. But he kills some Germans, and is killed, in the only battle-scene of Lawrence’s fiction which shows, I think, the fact that he knew his War and Peace. The story only becomes a meditation on Englishness, and the protagonist only becomes called Egbert, in the post-war version of 1922, in which it is noted:

He had no conception of Imperial England, and Rule Britannia was just a joke to him. He was a pure-blooded Englishman, perfect in his race, and when he was truly himself he could no more have been aggressive on the score of his Englishness than a rose can be aggressive on the score of its rosiness.

He had, however, the one deepest pure-bred instinct. He recoiled inevitably from having his feelings dictated to him by the mass feeling. (England, My England 27)

So it is presented as English to be individualist, as Lawrence was; though I confess that this makes me think of the chant in Monty Python’s The Life of Brian: ‘yes! We’re all individuals!’

We find this association of Englishness with contempt for national feeling again in ‘The Ladybird’, of 1921 – and this is the story with which I want to finish.

The heroine, who is based on Cynthia Asquith, briefly becomes the lover of a Czech aristocrat and officer of the Habsburg army interned and convalescing in England. Her mother Lady Beveridge, based on Cynthia’s mother, is active in benevolence towards all the locally interned officers.

Despite the fact that she has lost her sons and brother in the war, she will not hate:

the men who were enemies through no choice of their own. She would be swept into no general hate. Somebody had called her the soul of England […] throughout all the agony of the war she never forgot the enemy prisoners, she was determined to do her best for them.’ ‘The new generation jeered at her. She was no longer a fashionable little aristocrat. Since the war her drawing-room was out of date.

(The Ladybird, The Fox, and The Captain’s Doll 157)

The story itself does not jeer at her, though it does find her somewhat conscious and willed; her attitude is very close to Lawrence’s. She goes around the wounded officers talking with them in German – linguistically hospitable, as so many of Lawrence’s stories are. Daphne even writes out the words of a German song, which Lawrence, who was practised at translating German songs, then translates for his readers.

Daphne’s husband, on his return from the Levant, also visits Psanek, and pulls political strings to get permission to host him with his in-laws, before he returns to Austria, or whatever country his estate now falls within.

This is the reaction of Daphne’s father: ‘Earl Beveridge, whose soul was black as ink since the war, would never have allowed the little alien enemy to enter his house, had it not been for the hatred which had been roused in him, during the last two years, by the degrading spectacle of the so-called patriots who had been howling their mongrel indecency in the public face.’ (205) Lawrence likewise went out of his way and pulled on such strings as he had, to host German in his writing, and here he acknowledges that part of the motivation was his hatred of British patriotism. When they meet, Beveridge and Psanek agree: ‘We have all lost the war. All Europe’ (208).

It is significant that Psanek is not German but Bohemian – like Poland, a complicated nationality. His name is hybrid: Count Johann Dionys Psanek. He himself feels that he transcends nationality, and he does so in a more transcendent way than does the Beveridges’ English individualism.

He says: ‘The sun is neither English nor German nor Bohemian’ ‘I am a subject of the sun.’ (170) He then regales Daphne with esoteric knowledge derived from Egyptian cosmology. He explains that the ladybird on his heraldic crest is a ‘descendant of the Egyptian scarabeus [which first set the globe rolling] So I connect myself with the Pharaohs: just through my ladybird.’ ‘I am no Egyptologist’, said Lady Beveridge, ‘so I can’t judge’ (209-10).

No more – for sure – am I or can I. But this defeated Habsburg officer’s sense of connection to Egypt returns us to the country which set this lecture rolling – a country disputed between rival powers, but which itself produced myths that resonated in many countries, and songs that provided the Urtext for both German and English poetry which attempted to bridge national divides, even at a time of war. Lawrence may never have got to Egypt physically, but its culture – ancient and modern – had served his desire to speak to All of Us, very well.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

References to Lawrence’s works are taken from the Cambridge University Press editions. For biographical information, the Cambridge biography of D.H. Lawrence was consulted. Translations from German to English are my own.

Cram, David and Christopher Pollnitz, ‘D.H. Lawrence as Verse Translator’,

Cambridge Quarterly, April 2001 xxx 133-150

Delany, Paul, D.H. Lawrence’s Nightmare: The Writer and His Circle in the

Years of the Great War,London: The Harvester Press, 1979

Kimber, Gerri, ‘A Fragment of an Unknown Play by Tennessee Williams’,

3rd September 2014, Times Literary Supplement, http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1454212.ece (accessed 11.9.14)

Krenkow, Fritz, trans. and ed., The Poems of Tufail Ibn Aug al-Ghanawi and

At Tirimmah Ibn Hakin At-Ta’yi, Arabic Text, London: Luzac & co., 1927

Lawrence, D.H., Der Regenbogen (The Rainbow), trans. F. Franzius,

Leipzig, Insel: 1922

Schäfer, Heinrich, Die Lieder eines ägyptischen Bauern, Leipzig: J.C.

Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1903

Wilm, Jan, ‘German in the Letters of DHL’, Journal of D.H. Lawrence

Studies, 2013 3:2 85-107