This lecture was given at Rewley House, the Department of Continuing Education at the University of Oxford, on 11th October 2014, as part of a day course entitled ‘Twenty-First-Century Fiction’

The first thing to say about the topic ‘Russia in Anglophone Twenty-First Century Fiction’ is that there isn’t much.

And, indeed, this is not just true of the twenty-first century. Nor of the twentieth, nor the nineteenth, nor the eighteenth, let alone before that – although the lusty men of Navarre in Shakespeare’s 1598 Love’s Labour’s Lost do dress up as Russians, and Hermione Queen of Sicily in The Winter’s Tale is in fact Ivan the Terrible’s daughter; as she says at her trial, ‘The emperor of Russia was my father’.

The mother of the eponymous Daniel Deronda by George Eliot, set in the mid 1860s, marries a Russian prince and moves to Russia. Virginia Woolf’s Orlando has an affair with a Princess in the entourage of the Russian Embassy at the time of Elizabeth the First, as would have been possible. Notice, though, that none of these are actually set in Russia, only that they refer to it. The country’s only major place in twentieth century fiction has been in the spy thriller genre, of John le Carré, Ian Fleming, and others – the intensity of anti-Soviet feeling generally increasing in proportion as the literary quality of these thrillers declined.

A large part of the problem has of course been access. Before the Revolution, alone amongst European countries, Russia required its visitors to carry a passport. Then came the restrictions of the Soviet period. Orlando’s affair with the Russian Princess would in fact have been more possible than an affair between someone in the entourage of Stanley Baldwin (Prime Minister at the time that the novel was written) and a Soviet diplomat, given the non-existence of an embassy at that time due to the Zinoviev affair. Since the Soviet Union ended, tit-for-tat visa requirements, the slow development of mid-price-range hotels, and the general malodour in which post-Soviet Russia has been held, have deterred large-scale tourism thither.

The fact that over the last year and a half, during the Pussy Riot and Khodorkovsky trials, the Syria crisis, the Russian anti-gay law, Edward Snowden’s asylum, the Sochi Olympics and the crisis in the Ukraine, Russia has hardly been out of the headlines – but, as a brief comparison with other countries in the news will suggest, this is no guarantee that it will begin to feature in Anglophone fiction, even after the requisite time-lag for writing and publication. I asked Anthony Grayling, the Chair of the Booker Prize judges for this year, whether any of the nominated books concerned Russia; he said he could think of none none.

Yet it is surely a country which lends itself to fictionalization. Its very size requires a particular stretch of imagination to comprehend. Its uncertain cultural identity, as between Eastern and Western or a tertium quid, has led to the generation of competing myths about it, within the country itself. As young as America in many respects, in the nineteenth century it successfully invented traditions and projected an aura of antiquity, particularly concerning its purportedly defining quality – its dusha, or soul. Any country which thus invents and projects itself, including in its literature, and makes travel within it difficult, is ripe for external mythologising – and such has indeed been the case at the level of politics and of journalism – but Anglophone novelists, still more than Anglophone tourists, have rarely ventured there.

There are however exceptions, otherwise this lecture would have to stop here. The two I would like to discuss are A.D. Miller’s 2011 Snowdrops, and David Bezmozgiz’s 2014 The Betrayers, although I would also like to make honorable mention of Sebastian Faulks’s 2008 Ian Fleming-style James Bond novel set in 1967, Devil May Care, of which the heroine is descended from White Russian émigrés, and the villain is an expatriate Lithuanian who plays the Soviet Union and the West off against each other, to his own ends.

Snowdrops and The Betrayers are both by foreigners with experience of Russia, whose outsider protagonists – English and Israeli respectively – are culturally closer to many of the novel’s likely readers than are the novels’ Russian characters. Neither novel, as far as I know, has been translated into Russia, and in neither case do I anticipate this happening. Amazon and its equivalents, and ebooks, have hardly taken off in Russia, and therefore very few even Anglophone Russians will have had access to these novels, even if they wanted to read them.

Snowdrops, has, however, been translated into nineteen other languages, and was a BBC4 Radio book at bedtime. Its author A.D. Miller was the foreign correspondent of The Economist in Moscow between 2004 and 2007. The novel is set in Moscow during the period that Miller was working there, but its protagonist is not, autobiographically, a journalist – but an English lawyer working for an international law firm which arranges loans to Russian companies from Western banks – loans of precisely the kind which have recently been sanctioned.

There are two major plots and one minor one (plot spoilers follow). One of the major ones concerns Nicholas’s work, arranging a 500m dollar loan to a Russian company to build an oil pipeline in the Barents Sea. What Nicholas doesn’t realise is that the project is a fake, and that he therefore enables the transfer of the money to a man called the ‘Cossack’, who promptly dissappears. As a result, at the end of the novel Nicholas is recalled by his company from Moscow to England, where he is given a desk job with no contact with clients. This is the job he is doing at the time that he narrates the novel.

The second main plot concerns his private life in Moscow. One day by chance he rescues two girls from a mugging. He makes friends with both of them, and becomes the lover of one of them. They are sisters and have an aunt in Moscow. This aunt, Tatania Vladimirovna, has a splendid flat in the centre, but is thinking of moving to the pastoral quiet of the city’s Southern outskirts, where a friend of the girls is involved in a residential building project. Masha and Katia enlist Nicholas to do the legal work for the sale of her Moscow flat and purchase of her suburban flat. However, Nicholas is as much a dupe in this plot as in the other. Masha and Katia are not sisters; Tatiana is not their aunt, but a trusting woman whom they too are duping; their friend is not involved in the building project, but he is left as the legal owner of Tatiana’s flat; Tatiana is left homeless and, it is strongly implied, is murdered.

The third, minor, plot echoes the second one and concerns a neighbour’s friend who has disappeared. Again, he is murdered for his apartment, and only discovered the following spring, when the thaw reveals him to be a ‘snowdrop’ – a corpse revealed as the snow level falls. Around the time of the discovery, Nicholas’s culpability in the other crimes rises, like his own snowdrop, to the forefront of his consciousness.

The novel’s inclusion on the Booker prize’s 2011 shortlist was controversial, mainly because it is ‘genre’ fiction, specifically of the thriller genre. But it is also meta-generic. Nicholas is aware of the thriller genre, and sees the Moscow he experiences partly through its lense. For example, he describes his cynical expat friend Steve Walsh as ‘technically British, but he had been trying to avoid England and himself for so long and in so many far-out places […] that by the time I met him he had become one of those lost foreign correspondents that you read about in Graham Greene, a citizen of the republic of cynicism.’ When Nicholas first sees Masha she is wearing a ‘Brezhnev era autumn coat’ which ‘from a distance […] makes the girl in the coat look like the honey-trap in a Cold War thriller’.

It would seem that he likes his girls to look like honey-traps in Cold War thrillers, and that he likes the feeling of acting a part in a thriller, although he tends to displace this feeling onto other expats rather than acknowledging it in himself. He feels that he is superior to the expat lawyers who ‘generally only stayed [in Moscow] for two or three oblivious years, then retreated to service more reputable crooks in London or New York, sometimes as a partner in Shyster and Shyster or wherever, taking with them a handy offshore bank balance and some tits-and-Kalashnikov Wild East stories to console their live-long commutes’.

But Nicholas’s narrative itself includes ‘tits-and-Kalashnikov Wild East stories’ which are currently consoling his ‘live-long commutes’. The opening of his narrative, with the discovery of the snowdrop, echoes the opening of Martin Cruz Smith’s 1981 Gorky Park, another thriller set in Moscow.

But not only is he not fully conscious of his own desire to act in a thriller –he does not realise that he in fact is in a thriller. That his actions further a thriller plot, which he fails wholly to predict. He fails, therefore, at literary criticism of his own world. He thought that he was contemptuously likening Moscow life to gangster movie. It was appropriate, then, that the chair of the Booker judges that year was the former head of MI5. One would assume that a literary-inclined former-spymaster, if anyone, would have an eye for how reality can imitate fiction as well as vice versa.

The reader is positioned alongside Nicholas’s unnamed fiancée. The whole of the narrative is in fact, as gradually emerges, addressed to a woman whom he met after he returned to England from Moscow, and whom he is due to marry in three months’ time. The novel is his several-hundred-page answer to her question: ‘why did you leave Moscow?’. For a lot of the narrative one can forget that this is the frame – but occasionally Nick makes reference to ‘you’, to the fact that she knows what his parents are like, and so on. When he mentions that the area around the Kremlin is nice to visit, he adds ‘though I’m not certain we ever will’.

The reader is therefore explicitly aligned with – and looking over the shoulder of – an English person with no familiarity with Russia. This is the target readership of the novel, and gives the narrator an excuse to explain certain things which such a person wouldn’t know. When he mentions a place name such as ‘Ploshchad Revolyutsii’, he immediately gives the translation, ‘Revolution Square’. He has passable Russian, as Miller must. He tells us: ‘Most of the other foreigners managed to shuttle between their offices, gated apartments, expense-account brothers, upscale restaurants and the airport on twenty-odd words. I was on my way to being fluent, but my accent still gave me away halfway through my first syllable.’ When Russians speak low and fast – as Katia and Masha frequently do to each other – he can’t understand. They are on linguistic home ground, and in any conversation between Nicholas and Russians, it is decided by them which language is spoken. Nicholas comes to understand what he identifies as their ‘language game […] The Russian girls always said they wanted to practise their English. But sometimes they also wanted to make you feel that you were in charge, in their country but safe in your own language.’

The verisimilitude of the novel was implicitly attested by the descriptions of Moscow made in such English media outlets as Miller’s very own Economist. Simon Sebag Montefiore, the British historian of Russia, in his blurb for the front cover of the novel, praised its ‘darkly delicious Russian corruption and decadence’. The Guardian’s review of the novel argues that it ‘adds little to what we already know about life in Putin’s Russia: the cascading vulgarity of elitny shops and restaurants; the flesh bars with their painted girls and dwarves in tiger-stripe thongs; the top-to-bottom corruption; the gangsters.’ The implication is that there is no point in merely writing a thriller about modern Moscow, because from such a work of realism we would learn nothing new.

Nicholas’s tone in describing Moscow is however frequently dismissive – not just of those features cited by the Guardian’s review, but, as though by extension, of smaller and more harmless details: the metro have what he describes as ‘cloying year-round warmth’. The central Asian restaurants are dismissed as cheesy. Lenin has what he calls a ‘freak-show tomb in Red Square’. He makes ethnic characterisations of the Russians as people who could ‘wallow in mud and vodka for a decade, then conjure up a skyscraper or execute a royal family in an afternoon.” The ‘weasel President’ is described as ‘a mass murderer, like all Russian leaders as far as I can tell’. For all Nicholas’s naivety, such analyses on his part are not questioned by the novel.

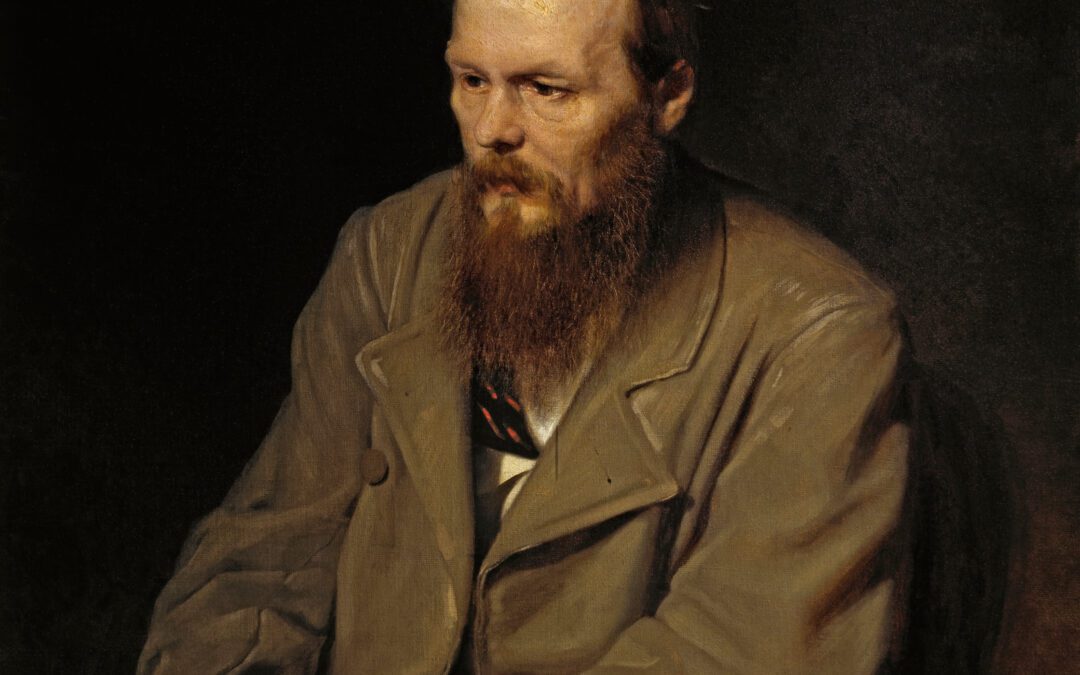

But he also reflects that Russia’s evil is probably matched by its exceptional good: ‘It’s a strange country, Russia, with its talented sinners and occasional saint, bona fide saints that only a place of such accomplished cruelty could produce, a crazy mix of filth and glory.’ This gives echo to a trope of Russian literature, notably that of Dostoevsky, by whom Nicholas is probably influenced in feeling it. It is not in fact strongly supported by the novel’s evidence, in which noone as degraded as Dostoevsky’s Fyodor Karamazov, nor as saintly as Sonia Marmeladova, exists.

Less clichéd, and more earthily expressed, is the point made repeatedly in the novel that the moral distinction between Russia and elsewhere is more apparent than real. Miller emphasised this in an an interview about the novel. In one scene, Nicholas describes the swindling Cossack as a ‘barbarian’ after he has left the room. At this, Paolo, Nicholas’s Italian colleague, explodes: ‘Mr English Gentleman, you think they do things so much differently in London? Yes, they are more subtle, ecco, more nice, more clean but it is the same. In Italy also. […] This Cossack is how we make our bonus, understand? No Cossack, no bonus. […] You and me, we are the fleas on the Cossack’s arse.’

But he is not a sober analyst of the country; he is, ultimately, intoxicated by it. This intoxication has two main components. First, living in Moscow he has the very common expatriate’s sentiment that there he is someone, a ‘corporate-law hero’ doing massive deals, skirting (as he thinks) danger, with the power of relative wealth, whereas in England he had felt that he was nobody – a lawyer with a safe suburban life, one amongst thousands. Second, in Russia he experiences an intensity of living which is not remotely matched by anything he had experienced in England. When Masha and Katia take him to a dacha, and they jump into the snow after leaving the banya, ‘The tingly pain proved that I was alive, every inch of me was alive, more alive than ever.’ He is addicted, that is, to what Miller himself called ‘the allure and the intensity of Russia’. This is particularly apparent when he goes home to stay with his parents at Christmas: ‘At the airport, as my passport was stamped, I felt the lightness everyone always feels, even if they love Moscow – the lifting of the weight of rude shopkeepers and predatory police and impossible weather, the lightness of leaving Russia.’ ‘Three hours later, in my parents’ Luton semi, I was howling on the inside and knocking back my father’s supermarket-brand Scotch’. He holds out through three days of awkwardness and boredom, then moves his return flight forwards and returns on New Year’s Eve. On leaving the airport he finds that the temperature has dropped a full ten degrees since he left – but he never for a moment regrets being back. Moscow is after all a place where stories happen, and the novel perforce stalls, along with his life, when he visits England. Nothing happens in England that Nicholas finds worth narrating before he moves to Moscow at the age of thirty-four.

The novel not only answers the fiancée’s question as to why he left – but the question of why he wanted to be there in the first place. The novel is a confession, since he is telling his fiancee that he was involved in major financial and violent crime and that he was in love and lust with one of the criminals. But he saves his greatest confession to the novel’s last page, and this confession retrospectively colours the meaning of all that has preceeded, and may derail his marriage. This is the last paragraph: ‘Of course when I think about it there is guilt, there is some guilt. But most of all there is loss. That is what really hurts. I miss the toasts and the snow. I miss the rush of neon on the Bulvar in the middle of the night. I miss Masha. I miss Moscow.’ The alliterative beauty permitted by Masha having a name beginning with M also perhaps hints at the profound connection between the two, because the novel does raise a question about agency – whether people like Masha make Moscow what it is, or whether Moscow makes Mashas. The first page of Lawrence Durrell’s 1957 Alexandria Quartet contains a pertinent thought: ‘I return link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city we inhabited so briefly together: the city which used us as its flora —precipitated in us conflicts which were hers and which we mistook for our own’. I would not go so far as to claim that the same is true of Miller’s Moscow, but certainly Snowdrops is not only the portrait of certain inhabitants of Moscow, but a portrait of the city itself, of which the name is the novel’s last word.

David Bezmozgis is Latvian Canadian; his parents emigrated when he was seven, in 1980.

His protagonist in The Betrayers is Baruch Kotler, born in the Ukraine in 1950. In his youth, decades before the time with which the novel is concerned, he became a Zionist refusenik, was denounced by a fellow Zionist KGB agent, and spent thirteen years in the Gulag, during which time he became the Soviet Jewish Nelson Mandela. On his release in 1988 he emigrated to Israel and became a minister. When, in 2013, he resists blackmail over his unpopular opposition to Israeli withdrawal of its own settlements from an unnamed area, he is exposed for having an affair, and decides to lie low by leaving the country with his lover Leora. This is the incident which the novel describes. Because of a nostalgic desire to revisit the location of a very happy childhood holiday he had fifty-three years earlier, they end up going to Yalta, where by chance they lodge with the woman whose husband is the KGB informant he knew in his youth. They meet, and have a lengthy, highly charged, moral argument. The informant Tankilevich explains that he had been a sincere Zionist, but that his brother had been under a death sentence for theft, and that he had been offered work for the KGB in exchange for his brother’s life. He had then been moved from Moscow to the rural Crimea, under an assumed name, and that he had been living crippled by guilt ever since. He asserts that through his betrayal he had in fact given Kotler the gift of international fame and adulation, a stellar political career in a country he loves, and, consequently, the ability to have a lover. Kotler had betrayed his own family in his refusal to compromise, whereas he Tankilevich had just betrayed a colleague. Kotler rejects these arguments, though he helps to ameliorate Tankilevich’s current, grinding poverty. Just twenty-four hours after arriving in the Crimea, he and Leora return to Israel, where Kotler’s soldier son has just shot through his hand rather than agreeing to obey orders to dismantle Israeli settlements. He is based on the real case of Anatoly, later Natan, Scharansky.

Now, despite the obvious differences, this novel has important similarities with Snowdrops, and it is unsurprising that there is an approving quotation from A.D. Miller on its front cover, which is: ‘Taut, fierce, compulsive’. Both novel’s protagonists have some of a wealthy foreigner’s contempt for what they perceive as the country’s absurdities and poverties. The somewhat, by Western standards, outdated and exagerrated fashions sported by Russian women in particular – such as dying their hair burgundy colour – are closely observed. They are both palpably both novels by men, concentrating on a male perspective. They are both more or less mocking of residual Sovietana: Bezmozgis’s narrator calls the towels in Kotler’s lodgings, which are not big enough to wrap round an adult waist: ‘masterworks of Soviet fabrication’, and calls the Khrushchevite-era bus line from Simferopol to Yalta a ‘triumph of Soviet engineering, the longest trolley bus line in the world. A typical Soviet triumph: scale over substance’ – as, in the post-Soviet world, it is possible for an anti-Soviet to observe without any frisson of fear. In both novels, the presence of Lenin statues are noted with irony: in Yalta ‘There is a Lenin Square ‘where, framed heroically by the Crimean Mountains, the bronze Bolshevik still stood on his pedestal looking intently out to sea – and peripherally at a McDonald’s. In times Kotler thought, the good citizens of Yalta might resolve, if not to add a pile of bones at his feet, then at least to replace him’.

Yet neither novel is much concerned with contemporary Russian politics. Snowdrops’s mention of the murderous president is isolated. So is the following quotation from The Betrayers about Russian state television’s Channel 1: ‘the newscast. Every lie starched and ironed. The pomp of a new agreement between Russia and western corporations to drill for oil in the North Pole. Which everyone knew meant billions of dollars to the same crooks. Condemnation of America for interfering in the affairs of sovereign states. Which meant defending the rights of Arab dictators to shoot their citizens with Russian guns. A clash between authorities and violent demonstrators in Moscow. Which meant the criminal regime stifling dissent. This was Moscow, Russia, and he was in Yalta, Ukraine. But it mattered little. Moscow, Kiev or Minsk. The same methods prevailed.’

And this equivalence between those three countries is echoed again when Kotler reminisces on the period after his release in the late 1980s, when he travelled the Soviet Union’s heseds, or Jewish communities, as their champion, and invited the country’s Jews to ‘come home’ to Israel: ‘And they had come. He didn’t flatter himself that it was because of his personal invitation. The main credit went to Yeltsin and Kuchma and Lukashenko for providing such excellent reasons to leave.’

He and Nicholas make similar sweeping, primordialist statements about Russian national character, alternately, or simultaneously, admiring and condemning, such as have characterised Western conceptions of Russia for several centuries. The Betrayers opens with Leora arguing with a receptionist who is denying them the room that they have booked in a Yalta hotel: ‘a pretty blonde girl, who endured the assault with a stiff, mulish expression. A particularly Russian sort of expression, Kotler thought. The morose, disdainful expression with which the Russians had greeted their various invaders. An expression that denoted an irrational, moral refusal to capitulate – the pride and bane of the Russian people. That Leora persisted in arguing with the girl proved that she was the product of another culture.’

As for many Westerners, some of the positive stereotypes are associated with the War; it is significant, in Devil May Care, that the Lithuanian villain Julius Gorner fought on both sides at the Battle of Stalingrad, initially for the Germans. Kotler’s taxi driver faces a long wait outside the Jewish centre in Simferopol. He is described as: ‘Reconciled to waiting by vocation and heredity. A stern relentless life, Kotler thought. Thus they’d sat in the trenches as the Panzers advanced.’

There is also some awareness, as there is in Snowdrops, of how Westerners come across to Russians: the narrator describes ”The [Yalta] vacationers in their Western fashions and their brash, contemptuous, cheerful, money-induced postures’. Yet there is also affection: Kotler observes that the phenomenon of getting up very early to sunbathe has remained unchanged since his childhood: ‘Was there another country who approached the phenomenon of leisure as systematically as the Russians?’ He characterises their parallel enthusiasms for natural science and folk medicine as: ‘The rival flows of mysticism and science that irrigated the Russian heart’. Both novels include positive recollations of the Soviet period. In Snowdrops the extremely positive character of the supposed ‘aunt’ is an ‘old communist’; in her flat, the one she gets swindled out of, there is a photo of her, significantly, in Yalta in 1956 – not long before Kotler would have arrived there – looking radiantly healthy and happy as, ‘Nicholas didn’t think Soviet people were meant to have been’. She had survived the Siege of Leningrad, and become happily married to a successful engineer and party member. In The Betrayers, Kotler warmly remembers his childhood holiday, in which he and his parents had lodged for a whole month with a family consisting of parents, their son, and his family. They all shared one kitchen and one toilet. ‘Simpler times’, as he thinks to himself. Though he is from the provinces – a village near Lvov, the Soviet education system had picked up his considerable musical talent and arranged for him to be sent to Moscow to study under a great musician.

However, the novel’s differences to Snowdrops are many and important.

Though The Betrayers feels throughout like a thriller – the atmosphere is as highly charged, Kotler feels in constant danger of being recognised as the refugee politician – it is in fact, as the front cover blurb claims, ‘a moral thriller’. The greatest violence which occurs is the shooting by Kotler’s son of his hand, and that takes place back in Israel. This is not just correlated to a difference of artistic inclination between the novelists concerned, but a difference of realia between the places which the novels describe. Yalta in 2013 had far fewer elements suggestive of the thriller genre than did Moscow in the early 2000s. Miller’s Moscow is lurid, sordid, and febrile; Bezmozgis’s Crimea is a placid, gently decayed backwater – respectively dangerously energetic, and pitiably passive.

The wild East does appear peripherally, however, in The Betrayers: the older brother whom Tankilevich saves by betraying Kotler serves eight years for theft and is then let out. As Tankilevich says: ‘While I sat in my Ukrainian village, he had Israel and America and Europe and even the New Russia. He traded. He did business, he had four wives, six children, and God knows what else. He lived like a king until some Moscow gangster put a bullet through his heart’. The narrator summarises: ‘His brother was a swindler, and Tankilevich had merely granted him the chance to live long enough to see the USSR remade in his image.’ That is, he might well die in the same city and at the same time as various characters of Snowdrops. He might even have become a snowdrop.

The reader’s possible expectations that a novel set in the post-Soviet world will be a thriller are both invoked and disappointed; the country has after all moved on and calmed down, and the tension generated is instead channelled into its moral debates, and the Israeli politics which are going on offstage. In the world of Snowdrops all action happens in Moscow; in The Betrayers it is all happening in Israel, a country with its own, different claims on the thriller genre.

The nostalgia felt by some for the Soviet period in Snowdrops it is more thorough-going, as fits with a novel more concerned with the Post-Soviet disaster. The novel makes scarcely any mention of Soviet oppression. In The Betrayers, Kotler catches The White Sun of the Desert being shown on television. Belye solutes pustyny came out in 1970. It concerns a Red Army officer’s conquest of Central Asia during the Civil War. It is comically exaggerated, but became a Soviet cult film, and it remains a much loved film in Russia, where quotations from it still abound in speech. For example ‘vostok, delo tonkoe’ – ‘the East, it’s a tricky thing’ – an understatement which regained bitterly new relevance at the time of the Chechen Wars.

In The Betrayer’s the film’s tone is described as ‘dry, laconic, gently mocking of the Soviet revolutionary myths’ acknowledges its knowing ironies and absurdities, but perhaps understates the extent to which its hero was in fact taken seriously as a hero. Tankilevich watches a game show on the Russian ‘Channel One’, and reflects ‘This was what they had raised from the scraps of communism. […] Bread and circuses. Mostly circuses. From one grand deception to another was their lot. First the Soviet sham, then the capitalist. For the ordinary citizen, these were just two different varieties of poison. The current variety served in a nicer bottle.’ In Snowdrops, the post-Soviet poison is decidedly the worse. This is understandable as a difference of perspective on the part of the authors. Bezmozgis being of Soviet origin and Jewish, feels with the difficulties which Jewish Refuseniks faced. Miller has, so far as I am aware, no such Soviet connection. The novels use different standards of comparison to contemporary Russia: Snowdrops a torpid and inconsequential England; The Betrayers an Israel which, if bitterly disappointing, and now producing its own returnees to Russia, as Kotler ruefully notes, is still invested with idealism and hope. To Nicholas Moscow is in every sense an adult place, whereas to Kotler Yalta represents his childhood and therefore the past. Nicholas is intoxicated. Kotler is gently moved to see what and how things have and haven’t changed, but, having scratched his itch of nostalgia, leaves the country, it is implied, for good. Both yearn for their adoptive countries, but only in the first case is this Russia.

This correlates with the fact that Snowdrops is eager to introduce its readers to the excitements and dangers of Russia, even to the extent of teaching us basic Russian and the basic layout of Moscow over the course of the novel. The Betrayers, by contrast, contains almost no Russian. The novel’s only memorable inclusion of foreign language appears when Kotler visits the Simferopol hesed and exchanges a few words with its Yiddish conversation group. Towards the end of the novel, Tankilevich’s non-Jewish wife Svetlana concedes to Kotler that Russians are anti-Semitic: ‘We were terrible anti-Semites. With repression and pogroms, our fathers and grandfathers drove the Jews from this country.’ ‘A hundred years later and the Jews are nearly gone. So this is a great triumph! But how do we celebrate? By bending over backwards to invent a Jewish grandfather so that we can follow the Jews to Israel! Ha! There is history’s joke. But tell me who is laughing.’ She explains: ‘This country suffocates its people. Slowly, slowly, until it finally chokes you to death.’ This could be scarcely further from Snowdrops, in which it is Luton that slowly chokes its people.

But The Betrayers’ acute awareness of ethnicity means that in fact its conception of Russia itself is more complicated than it is in Snowdrops. Admittedly, the latter has a soi-disant ‘Cossack’, and pays visits to Muscovite Central Asian restaurants, but its sense of Russianness is not troubled by these, whereas The Betrayers’ concentration on Jewish characters complicates what it is to be Russian, particularly since, shunning the Russian language, it is unable to use the pertinent distinction between russkii, ethnically Russian, and rossiiskii, which is a civic categorisation. The novel also suggests a parallel between the condition of the Crimean tatars and of its Jews. The Crimea was at one stage considered as a possible Jewish homeland: ‘Then the Tatars and the Russians could have demanded we go back to where we belong , as the Palestinians do now.’ As it is, thousands of tatars have returned to the Crimea in the post-Soviet period, and been admitted by the Ukrainian government, in part out of historical guilt. There is a scene in which unfinished buildings are described, strongly recalling the description of the indefinitely unfinished apartment block in which the ‘aunt’ in Snowdrops thinks that she is buying an apartment. But in The Betrayers this provokes a reflection not about corruption, but ethnicity: ‘It resembled, Kostler thought, Israel not so very long ago and, even to this day, the Arab parts of the country in the north and the south. The main difference was a peculiarity of the landscape’. The unfinished buildings. ‘Could just as easily have been new and unfinished as old and decaying. But if they were old, Kotler didn’t remember them from before.’ This aspect of the Crimea as new and pioneer-like cuts across its aspect of stagnancy, but only through the invocation of another people’s vision.

There is also, finally, a difference in the way in which morality operates in the two novels. Snowdrops endorses certain values, such as honesty, and kindness – but candidly sets alongside them the amoral imperatives of intoxication, of missing Masha and missing Moscow. The Betrayers, by contrast, projects itself wholly as a soberly judged moral novel, giving due empathy and generosity to the moral and personal claims of two opposed parties. It does have the moral wild-card of Kotler’s love and lust for his much younger lover, but by the end of the novel it is clear that he will leave her and return to his wife. To some readers, his Zionism will be understood as intoxicated and therefore amoral or immoral, but the novel does not present it in this light.

But one of the purposes of a day such as this, which concentrates on contemporary literature, is, I think, to consider the relationship of literature to life – so for this last part of the lecture I will do that, positioning the novels in relation to my own, limited, knowledge of what life in this century has been.

I briefly lived in Moscow in the early 2000s, the time at which Snowdrops is set. I have never visited the Crimea, let alone in 2011, which is when the Latvian Canadian Bezmozgis visited it in order to research his novel – so all my knowledge of the Ukraine is at second hand.

When I compare the world of Snowdrops with the Moscow I knew in 2002, it’s immediately apparent that the social classes described by the novel, and those with which I was connected, had very little connection. I was working as a teacher of English. I didn’t know any English expats, nor did I, to my knowledge, know any Russian gangsters, con-artists, or murderers. But one of m friends wasa banker working in finance for HSBC, and though I didn’t get the impression that he was involved in massive fraud, he was probably always involved in trying to avoid it. The flambuoyantly pornographic, hyper-self-conscious, nakedly wealth-orientated nightlife as represented by the novel accorded with my impressions of it – allowing for the important differences between the experiences of an expatriate woman, and of a man. At such places one did meet people one had every reason to suppose were gangsters.

Nonetheless, aware of the limitations of my perspective, I asked for the opinion of a friend who worked at an international law firm based in the very same crennellated tower next to Paveletskii station as Nicholas’s office is located in. This friend was dismissive of the novel’s quality as literature, but he considered it to be accurate: ‘I have been leaving in a rather rude and violent world, since such stories do not impress me at all. I believe that is because we see and hear similar things everyday’. He also wrote ‘I think every foreigner who has plans to live in Russia should read it, no doubt. While I was reading the only thought that always came across me is that I really felt miserably for him. I wanted to stop him and explain how things are in Moscow, to protect him, in other words. […] All in all, this story is an excellent and exciting guide for visitors, but it is everyday routine for Muscovites. […] I would definitely recommend it to people I know abroad.’

This is a striking endorsement of the novel’s verisimilitude, especially given that he was speaking in 2012, after a decade during which life in Moscow, on all indicators, has become steadily better, calmer, and less terror-ful. But since the progress has been steady, the difference between 2012 and 2014 may itself be relevant. There is also the possibility that my friend wished to impress a Westerner with the toughness of the reality with which he had to deal. For such reasons, Snowdrops already has the character of historical testimony.

If that is true of Snowdrops, published three years and set twelve years ago, how much more is that true of The Betrayers, despite being published this year and set last year. As Bezmozgis noted in an essay: ‘world events conspired to undermine my designs for the book.’ For one thing, a novel can take several years to write, and as he says: ‘I kept changing when the action was set, constantly pushing the date ahead by another year—2011, 2012, 2013, 2014—to coincide with the year of its ultimate publication.’ With regard to the events in the Ukraine which started with the protests on Maidan Square in winter 2013, he writes: ‘I felt frustrated that world events conspired to undermine my designs for the book. I’d wanted to write a novel that, among other things, engaged with current politics and that, in fact, even gestured at a modest prescience. As I was writing the book, I closely followed the news to see if real events had yet outpaced my inventions. I expected this to happen at any moment in Israel, where things always seem to be on the verge of upheaval. And yet, as I write these words, it isn’t Israel that has undergone a transformation but Ukraine and Crimea, places I’d believed to be locked in a dismal kleptocratic stasis.’ As he dryly puts it, ‘setting my novel in the summer of 2014, as I’d intended, is no longer feasible.’ So he sets it in summer 2013. He reflects on the now-yawning contrast between the speed of news updates, and the slowness of the fiction publishing industry, with its typical one-year lag-time between submission and publication. It is increasingly difficult to publish what is received as a novel of sharp topicality. This being the case, the novelist must fall back on literature’s claim to persistent relevance through its identification of durable perceptions. He writes, ‘if, in our infinitely variable and bizarre world, circumstances change, [journalists] will be given the opportunity to revise. The novelist who tackles social and political phenomena has quite a different position. He must posit a world and commit to it fully. He cannot merely describe—he must anticipate an outcome, if only a little. If a work of journalism is a solid structure made of facts, the novel is a moral and imaginative leap from atop that structure. And the pleasure for the reader is the pleasure, in the first instance, of watching an intricate edifice get built, and, in the second, of seeing someone leap without a net and, ideally, of leaping with him.’

Yet he also recalls that Philip Roth, in his essay “Writing American Fiction”, worried about novelists’ inability to invent a world that was imaginatively equal to our absurd and almost unaccountable reality. Snowdrops aspires to encompass that reality within the thriller genre; Bezmozgis was aware that the less violent The Betrayers, even at the moment of its publication, had fallen short of this.