This review was published in the ‘Newsletter of the D.H. Lawrence Society’, December 2013, and is reproduced by kind permission of the editor, David Brock.

Summary

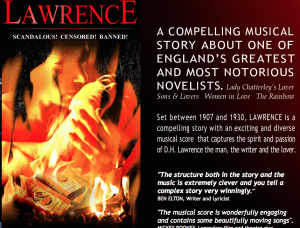

Glyn Bailey’s musical (now called Censored) about the life of D.H. Lawrence, performed at the Bridewell Theatre in London, was entertaining, deeply felt, and ultimately moving – though somewhat trivial and misplaced in its criticisms of the Anglican Church, and not the kind of entertainment of which Lawrence himself would have approved.

LAWRENCE Scandalous! Censored! Banned!

The Musical Based on the Life of D. H. Lawrence

Dr. Catherine Brown

Music and Lyrics by Glyn Bailey

Starring Bart Shatto as D. H. Lawrence

Directed by Keith Thomas

Book by Keith Thomas, Glyn Bailey, Theasa Tuohy Orchestration by Ricki Holmes

The Bridewell Theatre, London, 22-26 October, 2013 http://www.lawrencethemusical.com

My first response when I heard that a musical about Lawrence existed – and was coming to London – was incredulity. Admittedly, Lawrence was a man of many parts: creator, analyst, critic, preacher, theologian, satirist, painter, and writer of all the major genres – but he was never a musician. And the types of humour, performativity, and celebration associated with musicals offer no obvious fit with his character, works (including the plays), or place in his readers’ consciousness. Musicals were an important genre of entertainment throughout both his life and the period of his greatest popularity (the fifties to sixties), but one intuits no strong connection between the fans of that art form and this author. They demand different kinds of attention.

Then I thought again. Between which subject and which musical is there not a degree of disjunction, which adds to the latter’s very attraction? Admittedly, the most famous of biographical musicals – Evita (of which Lawrence composer Glyn Bailey performed in the London production) – concerns a show-woman, who performed her life infront of a popular audience, in a way that Lawrence did not. But apparent disjunction between content and form is by no means uncommon in musicals. Eliot’s modest and whimsical Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats was hardly an obvious candidate for high-decibel projection across the enormous theatres of the 1980s. The interaction of pirates with the population of Cornwall, the bloody defence and defeat of the Paris Commune, the life and death of Jesus Christ, missionary work undertaken by Mormons in Africa, and the life and suicide of osteopath Steven Ward are all gloriously dubious subjects for what have turned out to be (or in the case of the last, may turn out to be) successful musicals. Why, then, might it not work with Lawrence? I reasoned that any performance which reminded the world of the man and his writing, without rendering either ridiculous by intention or accident, was to be welcomed.

The programme, and a chat with composer, librettist, and book writer Bailey, revealed some fitting contexts for the venture. Bailey was born in Nottingham, and ‘has spent much of his life travelling, working and living in other parts of the world. It was Lawrence’s mixed feelings towards the town and country of his birth that first inspired Bailey to embark on this project’. Moreover, ‘It was whilst performing on a cruise ship that Glyn Bailey first had the idea of writing a musical about one of England’s greatest novelists’. One imagines Glyn retreating to his cabin and sketching out the tunes of ‘Scandalous!’, ‘I Hold My Future in My Hand’, and ‘I Will Rise Like The Phoenix’, rather as one imagines Lawrence in his cabin on his way from Sydney

to San Francisco scribbling out Fantasia of the Unconscious. Unlike Lawrence’s works, which received a mixed reception in Eastwood, the first, dramatised concert version of this musical premiered there in 2000. Thereafter it was developed through workshops in the USA as well as the UK, and became in several ways a British- American co-production. The orchestrator and choroegrapher of the current version are English, but its conductor and script consultant are American; the actors playing Lawrence (Bart Shatto) and the Priest (Nick Wyschna) are American, but most of the rest of the cast are English, and the bookwriters are a trans-Atlantic team. Given the relative warmth with which American readers responded to Lawrence’s works, and the importance of America not just to the evolution of his thought but the health of his finances, this American involvement is apt. The second and third productions (of what was by now a full musical) were also in England, at Guildford’s Bellairs Playhouse and the Nottingham Playhouse, but in 2009 the musical played in New Orleans, acquiring American cast members and, perhaps, something of its current Broadway flavour and polish. Now it has returned, as Lawrence did, from America to London.

Bailey was not satisfied with the first version of his work, any more than Lawrence was with the novel which it features most heavily, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Over the decade since 2000 the musical has been intensively developed in distinct successive versions. Admittedly, Lawrence did not tend to revise his own titles (he had his arm twisted by publishers over them), but he cannot be described as gifted at choosing them (Sons and Lovers is the only strikingly good one). So it is apposite that Bailey had some struggles over his title. The Eastwood version was called Country of My Heart – a site-appropriate quotation – but this by 2006 was altered to Lawrence’s emblem, Phoenix, and in 2007 to Scandalous!, which in 2012 was adopted by a different Broadway musical, resulting in a further change to LAWRENCE: Scandalous! Censored! Banned!

But it is Scandalous! that remains literally and otherwise at the heart of this title, as well as naming one of the musical’s catchiest numbers. It sums up the focus and attitude of the musical: that Lawrence was seen as scandalous when he shouldn’t have been. A high proportion of the numbers, sung by the likes of a Priest, prosecutor Herbert G. Muskett, and the company at literary luncheons and soirées, concern this reaction. The musical opens with the dying Lawrence, in a wheelchair, facing abuse to the last. There are of course other types of number, notably those concerning Lawrence’s relationship with Frieda (‘The Most Wonderful Woman’), but their palpable context is the narrative of Lawrence contra mundum. Given that the agenda is set by Lawrence’s critics, certain other things are necessarily left out: the Native Americans of New Mexico and Mexico, Lawrence’s psycho-physiology and his psycho-geography, his sensitivity to flowers, and his sense of God. This is not in itself a problem; what the likes of Herbert G. Muskett objected to in him is hardly peripheral to his thought.

But I would make two observations. First, the attack on Lawrence is led not only by Muskett (also the symbolic hate figure in Christopher Miles’s wonderful 1981 biopicPriest of Love), but a generic Church of England Priest. This is less fair – particularly when the priest in question whips off his cassock and reveals himself to be rather partial to rereading Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The Church of England was not at the forefront of condemnations of Lawrence during his life or since, and John Robinson,

Bishop of Woolwich, spoke bravely for Lady Chatterley’s Lover at its trial; yet the musical’s priest is a saucy hypocrite of a Carry On charicature.

Second, although the musical purports to cover the years 1907-1930, it is implicitly also very concerned with 1960, and with the novel which appears, being burned in its Penguin edition, on the play’s poster. The moral victory which the musical celebrates is that of the defendant in Regina v. Penguin Books, concerning Lady Chatterley’s Lover. It was therefore (queasily) appropriate that the one theatrical production for which the programme contained an advertisement was Cinders: The Adult Panto(‘Will Cinders finally enjoy one of the Prince’s magnificent balls?’ ‘Fun for NOT all the family’) – which is precisely the kind of work which Lawrence would have condemned, but for which the trial of his last novel made the world safe. The battle which Lawrence’s reputation has had to fight for the last four decades – and is still not winning – is the 1970s second wave feminist critique. Of this the musical gave no hint – doubtless in part because it had little resonance in Lawrence’s own time – but if one is concerned with defending Lawrence as well as celebrating him, then this is something for a future dramatisation of Lawrence to address.

The Lawrence who was presented in the musical grew from a geeky but ambitious youth to a saint and martyr with a redemptive vision of sex. The actual Lawrence’s priggishness, self-contradiction, and rages did not appear. Nor did his humour, which flashes and flushes throughout his work, by turns wicked, facetious, wry, genial, and savage. The humour contained in the musical lay in Lawrence’s situations, not the man, as expressed in numbers such as ‘Bertie’s Girls’ (Jessie Chambers, Lawrence, Alice Dax, and Frieda). Of course, characters are necessarily flattened in musical theatre, just as they loose their (Eastwood) accents when they sing: Lydia Lawrence and Jessie lacked brittleness; Alice was stylised as a gamey vamp. Such simplification is all the more inevitable when a musical belongs as decisively to the mainstream tradition of musicals from the 1930s onwards as this one does, with its Hollywood- Broadway bravura and idealism.

One can alternatively imagine a Lawrence: The Opera (or indeed The Ballet), which would reach closer towards the feeling of Lawrence’s works themselves. It would be avant-garde, with expressionist landscape sets, a scene of masturbation in vegetation, music which worked up to climaxes, and sex more transfixingly present than it was in this family-friendly musical (which somewhat disappointed the promise of its flamy poster, showing a woman with outstretched neck held by a large hand, and a male mouth descending). Such an opera/ballet might be inspired by the Ballet Russe, which Lawrence so admired.

But the intention of this work was not to interpret, illustrate, or imitate Lawrence, but to celebrate the later twentieth century’s acceptance of some of his perceptions, and to sing a hymn of praise to him for having made and campaigned for those perceptions. The cast themselves emanated this celebratory spirit, through their highly polished performance. The orchestra of six did their work, flawlessly, out of sight (though I wished that they had been allowed to nod, in the Eastwood scenes, towards the brass bands of mining communities). There were many memorable numbers, including ‘Scandalous!’ (Muskett, Two Women, Man, Priest, and Lawrence), ‘I’ll Be a Writer’ (Lawrence and Jessie), ‘The Most Wonderful Woman’ (Frieda, Lawrence), and, best of all, ‘I Will Rise Like The Phoenix’ (Lawrence and Company). The tenor Bart

Shatto had a slimness, fairness, and sensitivity of face which embodied Lawrence well. Jessica Sherman as Frieda was indeed a rather ‘Wonderful Woman’, and Darren Street offered a fitting and memorable mixture of thuggishness and charisma malgre lui as Arthur Lawrence.

Lawrence himself is unlikely to have approved of this musical – not because of its interpretation or presentation of him, but because he did not much like popular music or entertainment. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover Mellors describes the colliers as ‘a sad lot, a deadened lot of men: dead to women, dead to life. The young ones scoot about on motor-bikes with girls, and jazz when they get a chance. But they’re very dead’. When Connie is taken by her sister to the Venice Lido, it is reflected that ‘that was what they all wanted, a drug: the slow water, a drug; jazz, a drug; cigarettes, cocktails, ices, vermouth – To be drugged! Enjoyment! Enjoyment!’ (LCL 300, 259). Musicals offer the same kind of pleasure, and escape, as the jazz here condemned; this one even contained a jazz number, ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’. A gifted and well-produced musical, it offered plenty of ‘Enjoyment!’.

And yet it was moving – and not escapist – to have Lawrence so emphatically and professionally celebrated on the stage, in England, in 2013. The Bridewell Theatre is a community theatre developed in a long derelict Victorian swimming pool; risen out of the ashes, as it were, of surpassed and derelict Victoriana. The theatre offers lunchtime performances for city workers. One has the sense that this is a theatre which does good works. Hosting this musical was one of them. The auditorium, if not large, was full, and the audience was warm – something which is true in my experience of Lawrencians in general. The final number, ‘I Will Rise Like The Phoenix’, with its last line ‘I’ll never die again’ enacted its own prophecy so far as it could, in being sung and being witnessed. That was worth being there for.