Dir. Andrei Zvyagintsev (1964-), Arte France Cinéma, Why Not Productions, released 13.5.2017, 128 minutes.

To start with the first thing we see on screen: Нелюбовь.

Russian film director Andrei Zvyagintsev explains:

‘The English translation of the title does not fully convey the weight and meaning of the Russian title which is literally non-love, the opposite of love, not devoid of love which is what loveless implies. It’s not hate, it’s not indifference, it’s hard to say and the reason I brought this up is because the Russian title sounds even more pessimistic.’

So нелюбовь is a noun not an adjective, and the film is about that thing: the non-love which mutually connects Boris and Zhenya – a contemporary, bourgeois, Muscovite divorcing couple – and which connects both to their twelve-year-old son Alyosha (a name with connotations of innocence, being that of the saintly youngest Karamazov brother in Dostoevsky’s 1880 novel). Part way through, Alyosha disappears. The rest of the film concerns his parents’ unsuccessful effort to find him alive, whilst both of them pursue new relationships.

Despite its untranslatable title, this film has flourished in its subtitled life abroad: at the time of writing it has won twelve awards internationally (including the Jury Prize at Cannes, and Best Film at the London Film Festival, 2017), has been nominated for a further twelve, and is in contention for three more (including Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards 2018). It deserves such success; it is poised, penetrating and brilliant. The colours of its suburban Moscow, and of the film filters applied to them, may be mushroom greys and browns – and the camera may hold its gaze steady and grind exceeding fine – but the effect is that of a flashing gem.

Take, for example, the scene near the beginning when Zhenya (Mariana Spivak) and Boris (Aleksey Rozin) have a searingly ugly argument in front of their son. After some minutes of increasing wrath, Zhenya needs the toilet. What happens next I can only imagine happening in a German or a Russian film: the camera follows her. She doesn’t bother to close the bathroom door; the camera shoots her close-up and in profile as she wees, pulls up her knickers and jeans, perfunctorily dabs her fingers under a tap, clutches at a towel, and returns to the argument. We remain behind, as the camera swings round and peers behind the open door. There is Alyosha, his face covered in tears and his mouth agape in a voiceless scream of нелюбовь. It is a mask of tragedy, an image thrown into relief by the banality of peeing and hand-washing that precedes it – yet also guaranteed in its reality by that precedence. One of the differences between art and life is that only in the latter do women ever wee. Zhenya is a real woman, so her son’s anguish is real anguish.

Or take the moment near the film’s end when Boris and Zhenya are called to a run-down morgue to identify the mangled body of a boy matching Alyosha’s description. The stained tiles of the wall behind them permits them no retreat as they first squint at the uncovered body, then recoil in distress and tears – and then deny. ‘Это не он.’ ‘It’s not him.’ ‘It’s not him.’ ‘It’s not him.’ ‘It’s not him.’ Their faces are masks of grief and horror. Then again – ‘It’s not him.’ Art and life converge in uncertainty; we are not permitted the parents’ view of the corpse, to judge for ourselves. My own assumption was that ‘это’ is indeed ‘он’, and that we are seeing (a wonderfully acted) example of the phenomenon which the man who is showing them the corpse mentions as being common: a refusal to allow oneself to recognise a dead loved-one (or even, as in this case, a dead нелюбимый). Other critics have differed, and assumed that the corpse is not that of Alyosha, whose disappearance remains a mystery. DNA tests could establish it either way, of course, but perhaps Boris and Zhenya do not wish to take them – and wish to remain in tragic uncertainty rather than possible tragic certainty. We aren’t allowed to know this either. At the end of the film we see them, miserably, getting on with their separate lives.

Or take Alyosha’s disappearance. Actor Matvey Novikov is never a major presence in the film; his few scenes almost justify the content if not the contempt of his mother’s remark ‘he just cries’. The film’s main initial interest is in new relationships of both parents, which are in the first flush of lust, and of the relief of escape from intense marital misery. We see lengthy sex scenes, which, if departing from realism in choreographed elegance, are clearly not engineered to titillate, but rather to convey the importance of the sex to the participants. For Boris and Zhenya, sex is central to the sense of security, comfort, even любовь (Zhenya’s partner in particular is sympathetic) that they have in their new relationships – and this, the film successfully suggests, is why we need to see it. Early one morning, after a night of sex, Zhenya returns to her flat and flops into bed. Later that day she is roused by a call from Alyosha’s school. He has, it turns out, gone missing – just as he had long ago gone missing from his parents’ and the film’s concern. All of us have not been paying attention; now we will all spend the rest of the film searching for him.

A few things are worth mentioning about the very modern Moscow in which all of this takes place. Several characters spend much of their time glued to their iPhones, taking selfies, using social media; Boris’s girlfriend asks Siri to interpret her dream. Zhenya and Boris are comfortably off, as the police officer attending their case points out. Zhenya’s new partner Anton (Andris Keiss) is more than comfortable; his apartment resembles a show flat in a Thames-side new-build, all sophisticated greys, uplights, and matching bedding; a treadmill lives on the balcony. Yet no-one in the film is an oligarch. There is not a whiff of gangsterishness or funny money. These are middle-class professionals living a normal (if dysfunctional) life, as they now do inside as well as outside of Russia.

I thought back over the time that I have known the country. The first time I visited was on a rather mis-timed school trip, before I had any idea what Russia was, or my teachers had any understanding of the events that were taking place in it. It was December 1991, which turned out to be the last month of the Soviet Union’s existence. Moscow was febrile, almost but not quite panicked, and throngingly poor. ‘Jeans’ were a good present to give to people. Vodka bottles sold for the equivalent of 30p. Twelve years later, I returned to Moscow to live for half a year. There was no hint of panic now, but the city was depressed and rough. Western brands were sold at what I at first assumed to be ruble prices, but which were in fact hugely inflated and illegal US dollar prices. Wealth drove black-windowed vehicles with illegal flashing roof lights, with which it cut through traffic; it had bodyguards; it frequented restaurants where beautiful waitresses informed ingenuous English expats that there was ‘no room’ even though they were nearly empty; it frequented nightclubs where ‘feis kontrol’ screened men for wealth and women for beauty, and either for ‘krysha’ – a protective connection. Meanwhile poverty dragged its Chechnya-amputated torso through the snow on a skateboard, to beg. Professional ballerinas doubled as strippers. Professional musicians doubled as buskers.

One year later, when I returned on a visit, the situation had slightly improved. A year later, it was better still. This has been the consistent pattern of my near-annual visits since then; capitalism has been getting its gloves back on. Begging has disappeared; public facilities have improved. Western brands now have Russian rivals (the ‘Russia’ tracksuit that Zhenya wears in the last shot of the film is made by Bosco, a Russian sports brand). A bourgeois lifestyle resembling its London equivalents will cost a similar amount, and, as in London, is not a dodgy or edgy exception. In this sense, Loveless marks Russia’s progress. Russia has moved out of Communism, and the social-economic collapse of the 1990s, to the point that life for iPhone users is now as safe as it is normal. This film acknowledges the convergence between Muscovite and North-West European living standards by not commenting on the fact, but taking it as granted; Western critics of the film have done the same.

Another, less materialist, indication of improvement in Russia is the film’s depiction of civil society. When Alyosha goes missing, the policeman (after inspecting the flat, interviewing the couple, and ruling out the possibility that the latter have themselves kidnapped or murdered the child) explains that there is a limited amount the police can at that point do. In the vast majority of such cases, he says, runaway children return home within a week to ten days; the statistics are on their side. In the meantime, he suggests that Zhenya might like to contact a local group of volunteers who conduct missing-person searches; he gives her their details. From this point to the end of the film, the search operation is directed by that group’s leader, Ivan (Alexei Fateev).

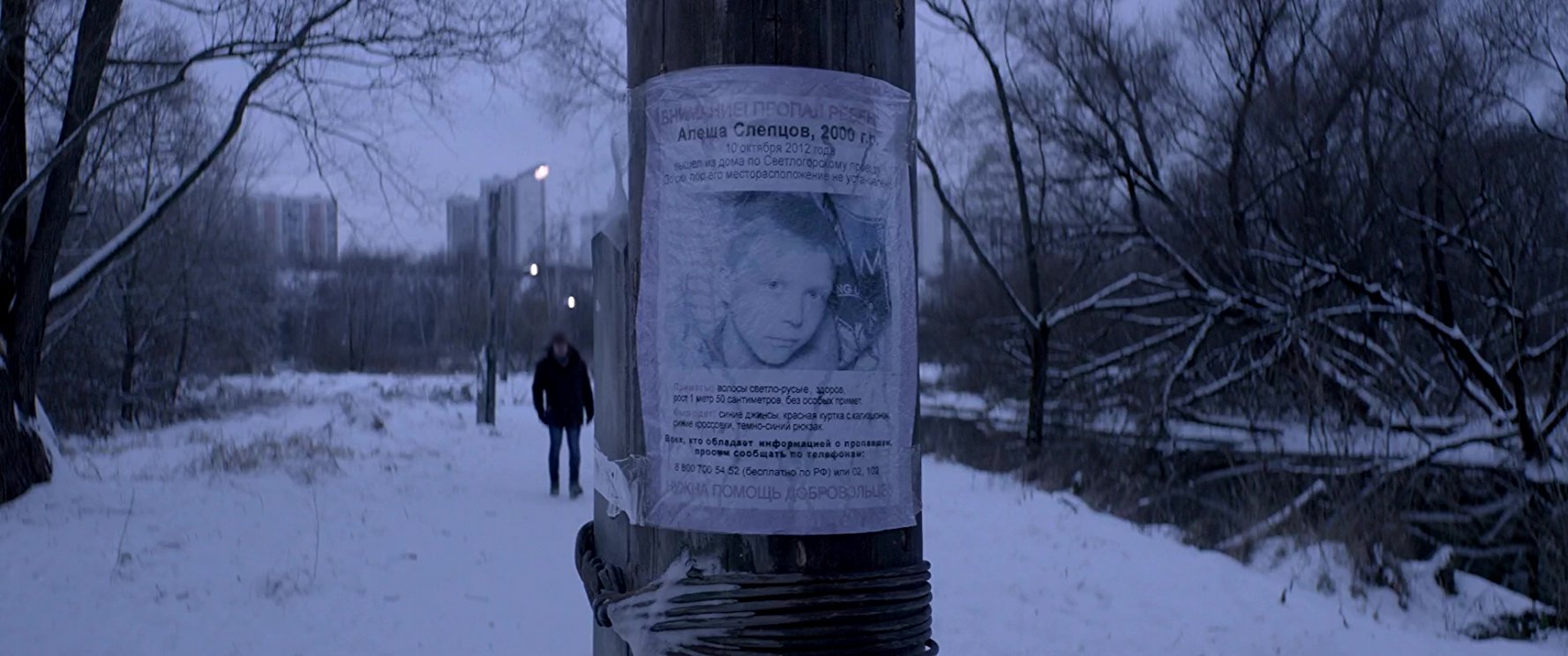

If there is a slightly iconic quality to the film’s other main characters (Zhenya’s harshness is somewhat stylised, as is that of her disturbed mother [Natalya Potapova], whilst Alyosha’s misery is total and archetypal), this extends to Ivan and his fellow volunteers. They are iconically good: totally professional, proficient, caring, and self-sacrificial. The group of about thirty has all the necessary kit, training, discipline, and procedure. Ivan gives clear, astute leadership, which is immaculately followed. He immediately recognises the fact that the missing child was unloved. One of his colleagues accompanies the parents on a lengthy journey to visit the grandmother, and searches the house diligently whilst Zhenya and her mother jab at each other’s emotional wounds over the kitchen table. Back in Moscow, the group organises searches of the local forests, and distributes ‘missing’ posters and flyers on underpasses, stairwells, notice boards, and benches. Gloved hands wind sellotape round and round the lamp-posts; they know how to put up posters that will last in the Moscow snow. As darkness falls and the snow increases, the search is not stepped down for the night, but intensified. Not one of the volunteers is discouraged or complains. Ivan handles the parents, and interviews Alyosha’s only school friend, with patience and astuteness. It is he who finally reveals the corpse to the parents, and he does so with compassion.

Who, then, is the film’s everyman? Is it the selfish Boris/Zhenya? (There are differences between them; her failings are partly explained by those of her mother, whereas Boris’s receive none – though it is she who is the more vicious. Yet in comparison to Ivan these differences become nugatory). Or is it Ivan, who is every bit as good and wise as Tolstoy’s ideal peasant Platon Karataev (who comforts Pierre Bezukhov when they are prisoners of the retreating French in War and Peace)? But he is no peasant. If there is no reason to believe that Ivan’s flat is quite as nice as that of the parents (money is clearly no motivator in his life), there is also no suggestion that he lives in contrastive poverty. He is simply an ordinary, but totally good, Muscovite: homo – truly – sapiens. So are his thirty nameless assistants. They outnumber the vacuous selfie-taking Muscovites seen in passing; they are, therefore, the Russians-en-masse of the film’s depiction; and they are banded together, in contrast to the atomised others.

The volunteers’ presence in the film does two things. First, it indicates a huge step forwards in the development of Russia’s civil society. It apparently has a real-world original – Liza Alert, founded in 2010 after the death in a forest of missing child Liza Fomkina earlier that year, and now operative throughout the former Soviet Union. Second, it balances the selfishness and dysfunctionality of the central family by suggesting the existence of a huge force for good, ready and available for deployment, amongst the mass of Russian people. The realm of нелюбовь is not limitless. It is worth making this point at length, because I am not aware of any other Anglophone critic who has made it at all. The volunteers are mentioned in other reviews in passing, but of the bright orange of their high-vis jackets no account is taken in descriptions of the film’s Russia as unremittingly grey.

Take, for example, Anthony Lane in The New Yorker: ‘As for the guilty party, blame Russia. The indictment that Zvyagintsev issued to his native land in his previous film, Leviathan (2014), was blistering enough, but Loveless is equally unsparing in its diagnosis of spiritual rot.’ Or Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian: ‘This is a story of modern Russia whose people are at the mercy of implacable forces, a loveless world like a planet without the full means to support human life, a place where the ordinary need for survival has mutated or upgraded into an unending aspirational demand for status, money, freedom to find an advantageous second marriage which brings a nice apartment, sex, luxury and the social media prerogative of selfies and self-affirmation.’ Neither mentions the volunteers, who somehow manage to proliferate on this ‘planet without the full means to support human life’. Owen Gleibermann for Variety does note that ‘a local citizens’ group is more proactive. They scour the area in their orange jackets and fatigues, leaving no stone unturned. As all of this goes on, the title of “Loveless” begins to expand’. Yet surely the reverse is the case: that the title’s realm of application is circumscribed as ‘all of this’ selfless labour, on the part of people to whom Alyosha is completely unknown, ‘goes on’.

The descriptions of the film as wholly damning of life in Russia also find themselves slightly confused between condemning the freedoms of capitalist materialism, and the lack of freedoms of Communist-style oppression. Anthony Lane continues his review: ‘There are shades of Solzhenitsyn in the way that Zvyagintsev condemns both the repressive machinery of the social order and the trappings that are proffered by the free market’. Certainly, there is a clear analogy between selfish, irresponsible consumerism and the breakdown of the parents’ marriage; they both trade up to better partners, acknowledging no responsibility to each other or to their child. But it is less clear what ‘repressive machinery of the social order’ Lane has in mind.

An inane radio station babbles to Boris about impending apocalypse as he drives to work. He clearly lives in a country in which there are exist some very stupid media outlets (as is indeed the case). But the connection between this and either state oppression or individuals’ selfishness is not clear and, I would argue, not argued for. Then there is Boris’s boss, a fundamentalist Orthodox Christian who requires his employees to be married with children; Boris fears that he will be sacked if his boss learns of his divorce. Such a plot line would be less plausible in, say, a British film. Wacky Russian bosses certainly exist; the West has just learned of one, Evgeny Prigozhin, who ran the Internet Research Agency near St Petersburg. But it is also not clear that the film is wholly dismissive of Boris’s boss. You cannot argue both that the film deplores a world of selfish divorces, and that it has nothing but derision for a world-view that praises stable marriages.

It is like the conundrum that faces critics of Anna Karenina: the novel’s critique of the Petersburg Society that turns its back on Anna at the opera does not preclude it from implying that Anna would have done better to have remained faithful to her husband in the first place (the more so since that Society shuns Anna hypocritically). Yet in Loveless there is no suggestion that Boris’s boss is hypocritically having an affair. Nor is there any suggestion that his stance has any causal relationship with Boris’s and Zhenya’s divorce. If anything, it is because positions such as his are now held by such a tiny, eccentric minority that behaviour such as the couple’s is unexceptional, and largely without social and legal cost to themselves. There is, admittedly, rather more social pressure on Russians than on North-West Europeans to get married if they are going to have a child, which is precisely why Boris and Zhenya marry when she accidentally becomes pregnant (it is her first relationship, and Boris’s young, pregnant girlfriend Masha iterates the pattern, with the chilling suggestion at the end of the film that their relationship will break down, and that their son is as unloved as Alyosha). But divorces are easier to obtain than in many Western countries, as has been true since Soviet times. Do the film’s Western critics think that Russia’s ‘repressive machinery of the social order’ repressively keeps divorce relatively easy, or the reverse? It is unclear.

The Moscow police is presented as lacking the funds to conduct a manhunt for every child who has been missing for two days; instead, civil society fills the gap (as it does in the UK, but not Russia, when it comes to the funding and provision of lifeboat services). This might in itself be deplorable, but the film neither stresses the complaint, nor attaches it to deliberate government policy.

Government policy is featured near the end of the film, when Zhenya is listening to – or rather ignoring – what one assumes to be a state channel’s radio broadcast about the Battle of Debaltseve in eastern Ukraine, which took place in 2015. Zhenya, wearing a tracksuit top emblazoned with the word ‘Russia’, leaves the room and gets on her treadmill, running slowly to nowhere with her eyes fixed on nothing. One could read this sequence as critical of Russian policy towards Ukraine, but such a reading lacks the support of Zhenya appeared to be approving of, or even listening to, the report. The news is presented from a Russian perspective; the same events would be differently presented on the BBC; but this is not an opinion programme, it is rather an update on events in a hot war. About this, Zhenya appears to care not at all. Again, the implication might be that Russian government policies are permitted by and/or productive of an apolitical people (Zvyagintsev says that he has never voted, because he does not think that his vote can have an effect), yet nothing about this scene suggests criticism specifically of Russian policy in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, this leaves the fact that Zhenya – who doesn’t care one way or the other about the fighting in Ukraine – has ‘Russia’ emblazoned on her Bosco tracksuit, and that the camera zooms in on it during the final shot. Mike D’Angelo writes in his review on The A.V. Club that ‘the film’s heavyhanded final shot makes it clear that Zhenya and Boris are meant to stand in for Russia itself’. I would agree that the shot is heavy-handed, and as such it diverges from the film’s normal mode. Nonetheless, such a reading relies on a different metonymic manoeuvre to that usually deployed in journalistic discourse about Russia, where ‘Russia’ (and anyone or anything Russian) implies ‘Putin and his government’. The ‘Russia’ metonymically implied in the final shot, by contrast, is the non-political masses of the country. And those masses, as we have already seen, are capable of forming themselves into remarkable forces for good. The film seems to end up forgetting that those volunteers ever existed, just as Boris and Zhenya probably do. When they forget, the film drops them. But by the same principle, it might be supposed that it does not in fact forget them, any more than it had actually forgotten Alyosha; these volunteers are still out there, doubtless spending their spare time looking for someone else, whilst Zhenya spends her own on her treadmill.

In his interview with The Independent’s Kaleem Aftab, Zvyagintsev not only criticises Russian capitalism: ‘To use other people as tools for your own purposes. This lack of empathy and this striving towards success, materialistic success is the basis of contemporary society, what is termed a capitalistic society’, but the government’s current Communist nostalgism: ‘They think it’s good to somehow install into the minds of Russian people that Stalin was not too bad. That he was an efficient manager who managed to take that peasant country and raise it to industrial progress and that it was a huge achievement. They are trying not to talk about the human sacrifice needed to make this happen. The authorities they have nothing new to offer so they are almost inevitably going back to the past.’ One could understand by this that in Zvyagintsev’s opinion the government is not offering a fresh, positive alternative to capitalist materialism. That would fit with a reading of the film as criticising the government for the existence of the non-love that it depicts, even though it does not prove it.

But such a reading relies on the assumption that it is a government’s role (or at least that in Russia it is the government’s role) to give people a reason – and rules by which – to live. It did so in Communist times. But my sense is that one message to be taken from the representation of the volunteers is that it is no longer for the Russian government to spiritually inspire its people, but rather for the people to think things through, and find bases for spiritual revival, for and by themselves. The Russian state as depicted in the film clearly does not repress civil society; on the contrary, the police rely on its help, and refer citizens to do the same. Whatever it does, the film does not suggest that a future, NATO-friendly government in the Kremlin could, should or would through its policies reduce the sphere of нелюбовь in Russia. This is not to deny that Zvagintsev is a critic of Putin’s government and of the current Russian political climate, but it is to deny that the film’s emotional politics may be mapped neatly onto ‘political’ politics, in the manner for which many of its Western critics have argued.

Indeed, it is clear that the film’s reception in the West has been leveraged to support the current discourse of Russophobia (which has many causes, and in my opinion involves culpable bias). Consider the title of Emily Yoshida’s review of the film in Vulture.com, ‘Loveless Will Make You Happy You Don’t Live in Russia (Yet)’. The parenthesis suggests that America (Vulture.com is run by New York magazine) is in danger of being taken over by Russia – a preposterously paranoid view, to which Putin’s strongest Russian critics themselves give no credence (for example Masha Gesson: ‘Loyal Putinites and dissident intellectuals alike are remarkably united in finding the American obsession with Russian meddling to be ridiculous’). Kaleem Aftab’s review and interview in The Independent is titled: ‘Loveless: How Russian director is taking aim at life under Putin through the ugliness of divorce’. For the reasons I have discussed, I consider that it is such reviewers, not the ‘Russian director’ himself, who are ‘taking aim at [life under] Putin through the ugliness of divorce.’ And Owen Gliebermann for Variety claims:

‘As a filmmaker, Andrey Zvyagintsev can’t come right out and declare, in bright sharp colors, the full corruption of his society, but he can make a movie like Leviathan, which took the spiritual temperature of a middle-class Russia lost in booze and betrayal, and he can make one like Loveless, which takes an ominous, reverberating look not at the politics of Russia but at the crisis of empathy at the culture’s core. […] A society rooted in corruption becomes a petri dish for a loveless marriage that spawns a family in which a child isn’t loved — that is, looked after — in the right way. And the result, seemingly out of nowhere (but not really), is tragic.’

As far as actual, financial corruption is concerned, it might be noted that Russia has risen from 120th (out of 183 in the world) in 2010 to 35th (out of 190 in the world) in 2017 on the World Bank Ease of Doing Business Ratings, which correlate strongly to presence and absence of corruption. Moreover, no corruption in this sense is depicted. As far as corruption in a looser sense is concerned, this is either tautological or not suggested by the film.

Such interpretations have certainly helped the film’s success in the West, as it previously helped that of Leviathan. But English interviewers have repeatedly found Zvyagintsev, and his Ukrainian producer Alexander Rodnyansky, resistant to such readings – suggesting that they themselves are resisting the temptation to cash in on them. In the New Statesman interview, entitled, ‘Oscar-nominated Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev is the thorn in Putin’s side’, Ryan Gilbey asks Zvyagintsev whether it was dangerous for him to work in Russia: ‘I don’t feel any danger’. The film is often described as having been refused funding by the Russian government; this sometimes involves contrastive retrospective acknowledgment of what was very much hidden at the time of Leviathan’s release in Britain, that the earlier film was funded, and internationally promoted, by the Russian Ministry of Culture. Zvyagintsev clarifies that he did not ask for state funding for Loveless; his main criticism of the government’s policy on film is, in fact, its protectionism towards Russia’s film industry. Nonetheless Loveless, like Leviathan, has been put forward by the Russian government for the Academy Awards.

In his Financial Times interview with Raphael Abraham, Zvyagintsev states: ‘I didn’t have the objective to criticise the state in this film. It was not at all what I was going for. What touches on the politics is just a background to the things that are going on in the film. All this propaganda that you hear on the radio in the film is just the real background which we Russians lived in from 2012 to 2015 because the main action takes place during six days in the October of 2012. And, then we see the characters after several years in 2015 when, already, all these tragic events between Russia and Ukraine have happened. They’re just the real background that we experienced in those days.’ In other words, part of the function of the mention of the Battle is to relocate the viewer to three years later than the main body of the action. The interviewer concludes sarcastically: ‘Of course. It is merely incidental background. It just happens to appear in a film about two warring parties who callously disregard the human cost of their actions’. But even this reading does not present the film at this point as critical of Russia in particular.

In his Chanel 4 interview with Zvyagintsev, Matt Frei pushes him to state that Loveless is about Russia as a whole. Zvyagintsev responds, with reference to the volunteers, ‘it is indeed in part about Russia, the revival of civil society’. Frei then suggests to Zvagintsev that he pulled his political punches in Loveless, and took the easy way out, because he ‘got his fingers burned’ with Leviathan. At this Zvagintsev recalls that ‘The state was actually very restrained in its response to Leviathan’, and observes: ‘I think we keep going round in circles in this interview.’ He clarifies that he thinks that this is because Frei belongs to a much more politically-active society than his own, and concedes that he would prefer his own to be otherwise than it is; but he insists both that he did not intend Loveless to criticise the Russian government, and that the reason for this is not an oppressive governmental response to his past or present work.

He insists that he is an artist, and on the universality of the film’s application: ‘My film concentrates mainly on human relationships, on human nature – not politics […] These human attributes exist in any political system’. This attitude fits with his claim that the film was originally conceived as an attempt to remake Scenes from a Marriage, the 1973 miniseries about a disintegrating marriage by Ingmar Bergman. Similarly, the film’s producer Rodnyansky, in an interview with Leo Barraclough on Variety.com, states that he:

‘is pleased that the crowds on both sides of the Atlantic have wanted to speak about “the art of Zvyagintsev” and the film’s overall theme — the devastating effects of selfishness — rather than focusing specifically on Russian society itself. “They appreciate his talent, his sophisticated cinematic language and his ability to come up with a strong message […] The story of human selfishness is universal. It is much more than a Russian tale of a couple going through a painful divorce.” […] Zvyagintsev is Russian so he, naturally enough, sets his films in Russia, but his stories are universal, albeit “told through the details of the only life he knows – life in Russia” […] The same selfishness depicted in the film can be seen “all around the world […] No one needs to know anything about Russia before watching the film. It’s a very understandable story of two people who feel the lack of empathy and the absence of love. It’s about their inability to communicate with each other, and their willingness to pay any price to achieve what they want.”‘

Certainly, uncaring and divorcing parents are widely distributed in the world. Capitalist materialism, apoliticism, and social media addiction likewise. Man hands on misery to man, and woman to woman, down the generations, in Larkin’s England and everywhere else. Police lack the funds to deal optimally with all problems, everywhere. Justin Chang in The LA Times writes: ‘Grim headlines about looming disasters in Ukraine and elsewhere blare from every radio and TV screen, drowned out by the vapid allure of Instagram feeds and other technological distractions’. Even taking this as a fair characterisation of the film, which it is not – could this not equally fairly be voiced as a criticism of life in the UK in the same period? With regard to the materialism, such reviewers are at risk of implicitly stating: ‘goodness, look at how superficial, materialist and selfish the Russians have become, now that they have come to resemble us, as we spent the 1990s encouraging them to do.’

We face, in Western reviews of Loveless, a problem faced by all reviewers of films set in countries with which they are not familiar: that, in the absence of other evidence, they take it as representative of that country. In the current case, we are dealing with a country about which the Western narrative is now so overwhelmingly нелюбящий that conformative interpretations are being foisted on it, which the director and producer feel obliged to contradict. As Rodnyansky said in the New Statesman interview: ‘Russia has its challenges and its demons, but it is also demonised itself in many ways.’ Indeed it has and indeed it is. Let not this fine product of its culture, which tries to confront those challenges and demons head on, provoke us to interpret it in a demonising manner.

(From L) Cinematographer Mikhail Krichman, actor Alexey Rozin, director Andrey Zvyagintsev, actress Maryana Spivak and producer Alexander Rodnyansky arrive on May 18th 2017 for the screening of ‘Loveless’ at the 70th edition of the Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, at which the film won the Jury Prize.