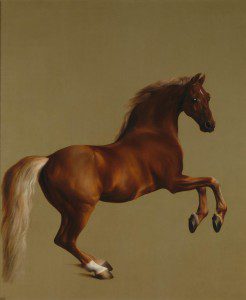

Whistlejacket, George Stubbs (1724-06), 1762. A portrait of the stallion Whistlejacket (1749 – before 1782). It should never be seen this small.

It’s called a levade, when horses rear in art. He’s an Arab, so it fits – from the land of rising suns. He rears, once for all, not in anger, pain or fear – but in excitement. He is up for it. Forever.

He was born in Northumberland in 1749, chestnut, mettlesome and fast. He raced through his second half-decade, winning Newmarket in 1756 and a four-miler in York in 1759 – beating Brutus, no less, by a length. Having been beaten four times only, he retired to reproduce.

After the Newmarket win he was bought by Charles Watson-Wentworth, second Marquess of Rockingham – thus uniting two great winners (the Marquess was later twice Prime Minister), and two great names. Whistlejacket was a cold cure made of gin and treacle, though it better suits a racehorse – all whistling by and horse jackets. Rockingham is a better name still, trumping Whistlejacket’s primus paeon with a magnificently racy, cantering, self-enacting dactyl. Of course the man didn’t have children. A name like that could never been born by a Victorian; far too much fun. Man and horse were a match made in an artist’s heaven.

Enter Stubbs, foremost equine painter of the age, friend of Rockingham’s, fresh from eighteen months’ horse dissection in Lincolnshire, full of anatomy and ready to paint.

The rest is history. The greatest horse portrait England has made.

And an enigma.

Why no background?

There are rumours. It was planned as an equestrian portrait of George III. Stubbs was to do the horse, a portraitist would mount the king, and a landscape painter would give them circumstance. Then this: Stubbs, to finish his horse, leaned his double against the stable and had the original led out, when the latter, seeing a rival, reared. Life imitated art; it took artist as well as groom to bring him down to earth. So word reached Rockingham, and he came to inspect. And decided that that was that. Not a stroke more. Whistlejacket alone. No king. No where.

Unlikely. Stubbs painted two other utopian pictures whilst at Wentworth Woodhouse: Whistlejacket and Two Other Stallions with Simon Cobb the Groom and Mares and Foals. Rockingham collected statues, and knew that classical forms were best seen on plain backgrounds. But you can see why the story lives. A canvas nine foot six by eight foot one. A horse nearly life-sized. It is larger than life. You could all but win Newmarket with it.

Rockingham, keeping his name well within the eighteenth century, bequeathed his house and painting to the Fitzwilliams. A later Earl Fitzwilliam gave a room in the former to the latter – the ‘Whistlejacket Room’, with only family portraits by Reynolds and Lawrence to keep it company. Then in the 1970s he hung in Kenwood House, so that his mind could run free on Hampstead Heath. The Tate Gallery held him from 1984–85. Finally in 1997 he was sold to the National Gallery, where he stares down a ten-room enfillade in the Sainsbury Wing from his place in Room 34. He is the Gallery’s Mona Lisa. He is its Mono Caballo.

He is neither racing nor mating. His penis is carefully out of sight, though from most angles on a rearing stallion it would be visible. He could be a mare. He is androgyne. It is of no matter. He is true to life. The distribution of white – a stripe on the nose and rear leg socks – is meaninglessly genetic. Then again he is Neo-classically idealist, with his Rubens-Velazquez levade and his perfect beauty. Then again he is Romantic, three decades before his time. He rears uncontrolled, natural and fully himself. Compare his free tail with that of Gimcrack or other of Stubbs’s horses – a brush cut just below the stump. Compare his form with that of Molly Long Legs or Tristram Shandy – his legs and torso are not lengthened into stylisation; he is rich in neck, chest and rump. A horse that could carry you further than most. Yet he is also beyond compare. He is not beneath humans, who do not exist. He is existentialist. Alone he constitutes himself in a moss-beige world. And is he not postmodern? His realism clashes with his background’s abstraction. Two cheeky shadows follow his rear legs. Yet there can be no sun without grass. Ceci n’est pas un cheval. Yet it is, my God it is.

Roger Robinson is a London-Trinidadian poet. This is his poem to Whistlejacket.

Stubbs’s Horse

Looking at Stubbs’s horse in the dark it becomes clear

He was no muscular glamourist, no fetishizer of fur and skin,

Convinced that the body was the host to the horse’s spirit,

He began making martyrs of horses, subjecting them to juggler death,

Beads of sweat rolling down their barrelled torsos,

Their eyelashes fluttering with a flourish,

Pumping them with warm tallow till their pulsing veins and arteries slowly came to a halt,

Suspended in a standing or a trotting pose by a series of hooks and tackles amid buckets of clotting blood,

Working his way through muscle by muscle, bone by bone,

Dissecting and designing limbs,

First stripping off the skin and other layers of muscle,

Turning pages in the book of horse.

So that even in the dark of the museum I can feel this horse breathing.