It is with some trepidation that I blog for the first time about Donald Trump.

It is partly because I feel such trepidation that I feel the need to do so.

Donald Trump is a gifted demagogue, an unwise, inexperienced politician, and an ignorant, under-principled President of the United States. In some of his long-held desires, and some of those produced temporarily by the influence of advisers, he threatens and damages individuals, peace, and nature around the world. The United States and all other countries would be much better off with a much better President, and I hope that one is elected to office as soon as possible.

There are however ‘howevers’. My good friend, the novelist Howard Jacobson, would classify me, with horror, as what he calls a ‘but-er’.

I was not one of those people who responded to the election of Donald Trump with unmixed anguish. Trepidation, certainly, but feelings that were mixed because:

1. It remained to be seen which of his stated policies Trump would attempt to, and would be able to, enact. A Clinton presidency would have been a relatively known quantity. The same was not true of Trump because:

i) Trump made mutually contradictory statements.

ii) it was unclear how much of what he wanted would be permitted by the US Congress and bureaucracy.

2. His stated policies on the following topics tended more towards domestic wellbeing and world peace than did those of Clinton:

i) foreign interventionism (reducing it)

ii) relationship with Russia (improving it)

iii) ‘the swamp’ (‘draining’ it)

iv) industry and infrastructure (investing in it)

3. The vote for Trump was, contrary to implausible claims that it was ‘all’ or ‘essentially’ racist, to a significant degree a protest against a corrupt, hypocritical, mendacious, plutocratic and imperialist financial-political-military system which deserved to be voted against.

4. The worst of the things that Trump had proposed, such as torture, would – I hoped – be prevented by political will and the rule of law.

5. Insofar as Trump represented prejudice and (contrary to his policy statements) the ‘swamp’ itself, I hoped that his presidency would energise those progressive forces in the United States which had regrettably and long been quiescent. Their newly-vigorous confrontation with the worst aspects of American life might help to finally purge America of the latter.

6. The extent to which Trump was different to and worse than Hillary Clinton and his own presidential predecessors was vastly overstated. A Mexican ‘fence’ already existed. Obama secretly put a six-month travel ban on Iraqis in November 2011. Guantanamo Bay’s inhabitants continued to be tortured throughout Obama’s presidency. The reason that I did not feel that the sky had fallen in when Trump was elected was that we had long been living amongst its shards.

7. Much of the criticism of Trump seemed to be stimulated by, and directed at, style rather than substance.

8. Trump had won the Republican primaries democratically, whereas Clinton had won the Democratic primaries corruptly.

Such were the more hopeful thoughts I had on the morning of November 9th, 2016.

Only a few of these hopes have been met.

Trump has represented the ‘swamp’ more than he has acted against it. He has been forced by ‘Russiagate’ to sign new sanctions against that country (which only Senators Bernie Sanders and Rand Paul, to their great credit, voted against). His policies towards and in Israel, Syria, Iran and North Korea have to an alarming degree undermined the prospects of peace in their respective regions.

These facts make successful opposition to Trump all the more important.

But the current opposition has limited success, and is in some respects counter-productive, because:

1. Trump is treated as exceptional – a far greater manifestation of American political imbecility and evil than any prior US President – in a manner which is not only inaccurate, but suggests that similar policies pursued in a classier, lower-key manner in a post-Trump future would be met with a renewed lack of opposition.

2. The exceptional reaction to him is stimulated in large part by a snobbish reaction to his style. Scales have not fallen from people’s eyes about the post-war nature of the United States; they have been selectively removed in order to gaze in amused horror at the spectacle of a man with allegedly ‘orange’ hair (as though the man might not have whichsoever hair colour he chooses, according to the [admirable] liberal principles of many of his mockers; and as though Trump’s comments about others’ personal appearance, for which they castigate him so loudly, excuse their hypocrisy). As American historian and political analyst Thomas Frank comments here, the ‘respectable press’ ‘know what a politician is supposed to look like and act like and sound like; they know that Trump does not conform to those rules; and they react to him as a kind of foreign object jammed rudely into their creamy world, a Rodney Dangerfield defiling the fancy country club.’

3. Much of the protest has focused on identity issues, such as race, gender, and sexuality, to the near-total exclusion of matters with more concrete and larger-scale implications for non-white people, women, and gay people – such as war. The relative reactions to Trump’s and Clinton’s campaigns suggested that it was of more importance to women that Trump had spoken of them sexually, than that US foreign policy might or might not involve blowing up hundreds of them up. This was true even of protest outside of the United States, which might be expected to concentrate more on US foreign policy. Such protests involved a degree of salaciousness. It was seen as more fun, carnivalesque, and modish, to protest against ‘pussy-grabbing’ than against war or the military-industrial complex.

4. Trump’s supporters have been inaccurately, unempathetically, condescendingly and counter-productively written off wholesale as racist trash. This is not only factually and morally wrong, but bad politics. As The Guardian columnist Simon Jenkins points out here: ‘it must be counter-productive to feed [Trump’s] paranoia, to behave exactly as his lieutenants want his critics to behave, like the liberal snobs that obsess him.’

5. The mainstream media’s criticism of Trump is so nearly-unanimous and so unvarying that it bores and irritates. As Frank says: ‘The people of the respectable east coast press loathe the president with an amazing unanimity. They are obsessed with documenting his bad taste, with finding faults in his stupid tweets, with nailing him and his associates for this Russian scandal and that one. They outwit the simple-minded billionaire. They find the devastating scoops. The op-ed pages come to resemble Democratic fundraising pitches. The news sections are all Trump all the time. They have gone ballistic so many times the public now yawns when it sees their rockets lifting off.’ ‘The news media’s alarms about Trump have been shrieking at high C for more than a year. It was in January of 2016 that the Huffington Post began appending a denunciation of Trump as a “serial liar, rampant xenophobe, racist, birther and bully” to every single story about the man.’

6. The real reasons for Trump’s victory and Clinton’s defeat are not being addressed. This is the single most important weakness of the anti-Trump movement and of the current Democratic Party. The reasons for Trump’s victory are domestic, but Russia is being used as a scapegoat. Even were the allegations of ‘Russiagate’ true, Russian actions:

i) could not plausibly account for the bulk of Trump’s support

ii) could not plausibly be proved to have given Trump specifically his narrow margin of victory

iii) cannot be undone, and can doubtfully be prevented in the future, in contrast to those domestic factors which have led to the bulk of his support

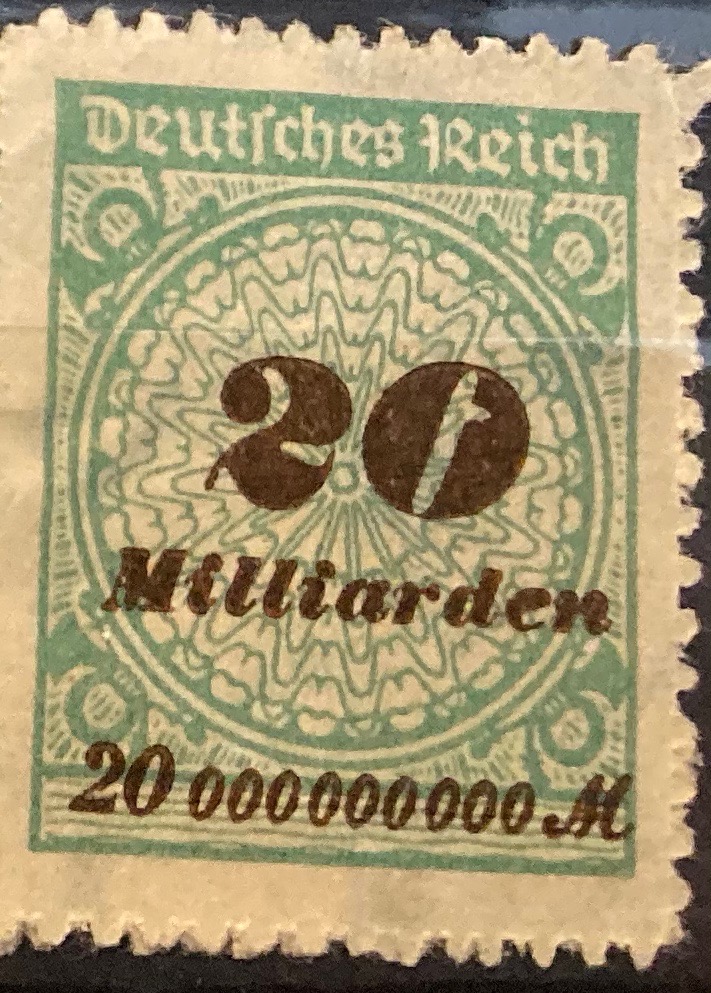

7. However, the substantial allegations of ‘Russiagate’ must be assumed to be untrue, since no evidence has been found to support them. The investigation has been going on since July 2016 and no proof of the hacking of the Podesta emails by Russia has been found. The Joint Intelligence Committee report of January 2017 rested on ‘assessments’ [i.e. guesses]. Prominent Putin critic Leonid Bershidsky describes here how Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity (VIPS) ‘don’t buy the Russia story’. Rather, to keep ‘Russiagate’ going, the goalposts have been continuously widened to include any normal, legitimate contact between any people connected respectively to Trump and to Russia – as former UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan, as Craig Murray points out here. The function of Russiagate to distract attention from the reasons for Trump’s victory are encapsulated in miniature in its success in distracting attention from the contents of the Podesta emails (damning and undenied proof of Democratic Party corruption) by blaming their alleged ‘hacking’ on Russia (which is without evidence). Indeed, the near-monolithic opposition of left-wing and right-wing tabloid and (especially) educated press to Russia has no parallel since the McCarthy era, when at least:

i) US spies for Russia were proved to have existed, as was alleged, if not in the same numbers

ii) Russia was far more to be deplored for its domestic policy, and was formally the enemy of the United States

iii) Many educated individuals were sceptical of or opposed McCarthyism. There is a frightening lack of such scepticism and opposition on the part of such people today.

Russiagate is damaging on all fronts.

i) It distracts attention from the real wrongs in which Trump is engaging at the level of policy, thus making it easier for him to perpetrate them.

ii) It distracts attention from the real reasons why Trump is successful, and provides false hope. As long-standing Putin critic Masha Gessen puts it here, ‘For more than six months now, Russia has served as a crutch for the American imagination. It is used to explain how Trump could have happened to us, and it is also called upon to give us hope. When the Russian conspiracy behind Trump is finally fully exposed, our national nightmare will be over’.

iii) It has little traction with Trump’s supporters, and therefore does not reduce his support. If Trump received proof of Democratic Party wrongdoing from Russia, they do not see why he should not have done so; and Russiagate’s ubiquity and shrillness in the US media confirms Trump’s narrative about that media.

iv) It worsens relations between two nuclear-armed powers, which have been operating in tension in a hot war in Syria since November 2015.

v) It is counter-productive with regard to Russia. Nothing in the most recent sanctions constitutes an inducement to Russia to change its behaviour in any way. The sanctions have stimulated Russian domestic investment, support for Russian brands, and distrust of the United States, whilst strengthening Russia’s financial and political ties with China.

vi) It is financially damaging to the European Union, with the sanctions preventing access to cheap Russian oil and gas for countries such as Germany, and the counter-sanctions having cut off Russia as an export market for food from countries such as Greece.

vii) It represents hypocrisy on a scale that it is almost impossible to comprehend. Since WWII, the United States has intervened, substantially and frequently lamentably, in more countries than any other. Trump is at present speaking openly about the possibility of military intervention in Venezuela. The United States strongly influenced Russian elections and domestic policies during the catastrophic 1990s. As Noam Chomsky puts it here, ‘Half the world is cracking up in laughter. The United States doesn’t just interfere in elections. It overthrows governments it doesn’t like, institutes military dictatorships.’

viii) Nestled within this hypocrisy is the smaller-scale inconsistency of accusing RT (the Russian state international TV channel) of being pro-Trump during the presidential election campaign, as the January 2017 Joint Intelligence Committee Report did.

It should be noted that:

a) RT had favoured the candidacy of Sanders over that of both Trump and Clinton more decisively than it subsequently favoured the candidacy of Trump over Clinton.

b) RT subsequently favoured Trump over Clinton less emphatically than, for example, the BBC favoured Clinton over Trump, but it is certain that no complaints would have been made about the latter’s influence had Clinton won the election.

c) There is no law in the United States requiring impartiality of foreign media entities operating in its territory during domestic election campaigns (in contrast to what the UK required of foreign broadcasters operating in the UK during the Brexit referendum).

d) US television channels have operated in Russia, and have expressed opinions on candidates in elections, throughout the post-Soviet era.

ix) Russiagate represents a failure of empiricism and scepticism on the part of educated people in general, and journalists in particular. As journalist Glenn Greenwald puts it here, ‘This kind of deranged discourse is an attack on basic journalistic integrity, on any minimal obligation to ensure that one’s claims are based in evidence rather than desire, fantasy, and herd-enforced delusions. And it’s emanating from the most established and mainstream precincts of U.S. political and media elites, who have processed the severe disorientation and loss of position they feel from Trump’s shock election not by doing the work to patiently formulate cogent, effective strategies against him, but rather by desperately latching onto online “dot-connecting” charlatans and spewing the most unhinged Birther-level conspiracies that require a complete abandonment of basic principles of rationality and skepticism.’

And this is Gessen: ‘What is indisputable is that the protracted national game of connecting the Trump-Putin dots is an exercise in conspiracy thinking. That does not mean there was no conspiracy. And yet, a possible conspiracy is a poor excuse for conspiracy thinking.’

Frank broadens this point to state that: ‘the unanimous anti-Trumpness of the respectable press is just one facet of a larger homogeneity. As it happens, the surviving press in this country is unanimous about all sorts of things. […] This is one of the factors that explains the many monstrous journalism failures of the last few decades: the dot-com bubble, which was actively cheered on by the business press; the Iraq war, which was abetted by journalism’s greatest sages; the almost complete failure to notice the epidemic of professional misconduct that made possible the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of Donald Trump, which (despite the media’s morbid fascination with the man) caught nearly everyone flatfooted. Everything they do, they do as a herd – even when it’s running headlong over a cliff.’

x) Russiagate represents a sudden extension of goodwill and credulity to the US security serves on the part of many people who had formerly and with good reason been sceptical of their honesty and goodwill.

xi) Russiagate constitutes a form of xenophobia. As Gesson points out: ‘Russiagate is helping [Trump] – both by distracting from real, documentable, and documented issues, and by promoting a xenophobic conspiracy theory in the cause of removing a xenophobic conspiracy theorist from office.’ A Russian friend of mine who lives in London described to me the recoil she sometimes experiences when she tells new acquaintances that she is Russian, and described Russophobia as an acceptable form of racism.

I will leave the last word on Russiagate to Craig Murray:

‘Those who believe that opposition to Trump justifies whipping up anti-Russian hysteria on a massive scale, on the basis of lies, are wrong. I remain positive that the movement Bernie Sanders started will bring a new dawn to America in the next few years. That depends on political campaigning by people on the ground and on social media. Leveraging falsehoods and cold war hysteria through mainstream media in an effort to somehow get Clinton back to power is not a viable alternative. It is a fantasy and even were it practical, I would not want it to succeed.’

8) Opposition to Trump has led to a making of common cause between progressives and neo-conservatives, whose principles and aims the former had opposed, in a manner which strengthens the latter. At the same time, the latter have ‘virtue-signalled’, as in the wake of Charlottesville. This is not a verb that I would use in any situation other than one in which a given virtue is propounded by parties who have no history of association with it, and have an independent political interest in so doing (in this case, achieving power).

9) The liberal/neocon opposition to Trump has focused on one of Trump’s best promises: to reduce US interference in other countries. Trump’s high level of support amongst families which produce America’s rank-and-file troops is based in part upon it. But it has been denounced as ‘isolationism’, a term which links it by implication to irrelevant historical contexts such as the two World Wars, and it is perversely presented as aggressive.

10) Point 9) has given Trump every inducement to resile on this promise, to break international law, and to undermine peace, by intervening. After he ordered the flagrantly-illegal bombing of Syria in April 2017, liberal US commentator Fareed Zakaria commented that with that act, Trump ‘became President of the United States’. With one act of illegal aggression, that is, Trump found that he could win almost the entire political spectrum ranged against him to his side.

11) Point 10) is not the only way in which opposition to Trump has threatened the law:

i) What is currently being attempted by Russiagate is a slow coup. As Gessen comments: ‘The dream fuelling the Russia frenzy is that it will eventually create a dark enough cloud of suspicion around Trump that Congress will find the will and the grounds to impeach him. If that happens, it will have resulted largely from a media campaign orchestrated by members of the intelligence community – setting a dangerous political precedent that will have corrupted the public sphere and promoted paranoia. And that is the best-case outcome.’

ii) Some of Trump’s opponents have on occasion been violent, and have abrogated others’ right to free speech, as in Charlottesville. The context excuses nothing.

iii) Some of his opponents have responded to the events in Charlottesville in a manner which closely mirrors’ certain other people’s reactions to Islamic terrorism: by arguing that the rights of the perpetrators, and of those who think similarly to them, should be abrogated.

Here Greenwald argues strongly and rightly for the universal application of civil rights in situations such as Charlottesville.

So, things have indeed been shaken up by Trump’s presidency, but not as I had hoped.

Certain liberals have made common cause with neocons, have given previously-withheld trust to the US intelligence services, and have incited Trump to interfere illegally and bloodily in other countries, whilst accusing him of being the cooperative beneficiary of the illegal intervention of a different country, which they have forced him to sanction in retaliation, without having proved that intervention, and at the expense of international peace, EU prosperity, and respect for truth. The man has been played, not the ball; opposition to Trump’s worst policies has produced opposition to his best. Focus has remained relentlessly away from the real reasons why Trump won – the negative features of American life which he correctly identified, and the negative features of American life which generated support for his false diagnoses and his false solutions – in a manner which makes his democratic removal less likely, and which works in concert with dangerously-undemocratic means of removing him instead.

Come on – anti-racists, anti-imperialists, feminists, LGBT-sympathisers, liberals, leftists, environmentalists, peace activists and democrats – we can do a lot better.