When Russians and Britons discuss literature – especially British fiction, especially if written since the Lady Chatterley trial of 1960 – a difference often emerges in attitudes towards sex. Russians, it seems, prefer sex to be done but not described, known but not displayed – which is one reason for the Russian distaste of Gay Pride marches, which the West misinterprets as principally homophobic.

For what it is worth, I think there is much to be said for this attitude. I too think that sex isn’t a spectator sport. Historically, of course, it was that to a far greater degree than at present. Whether one were a Russian peasant living with one’s family in a one-roomed hut, or a courtier in a corridor-less Petersburg Palace, one could easily find oneself witnessing sex. That is no longer the case for either oligarch or muzhik. Sex, if seen, is seen in ‘art’ – from filmed or staged pornography to literature. The difference is of course one of intention. Whereas neither royals nor peasants displayed their sexual activity – it was just hard to hide – today’s directors and authors choose to display sex, to be consumed at a distance.

An alternative to the Russian attitude is voiced by Patrick, editor of the novelist Michael Owen in Jonathan Coe’s 1994 novel What a Carve Up! He ventures the criticism of Owen’s work that it lacks sex: ‘I’m saying that there’s a crucial aspect of your characters’ experience which is simply not finding expression here.’

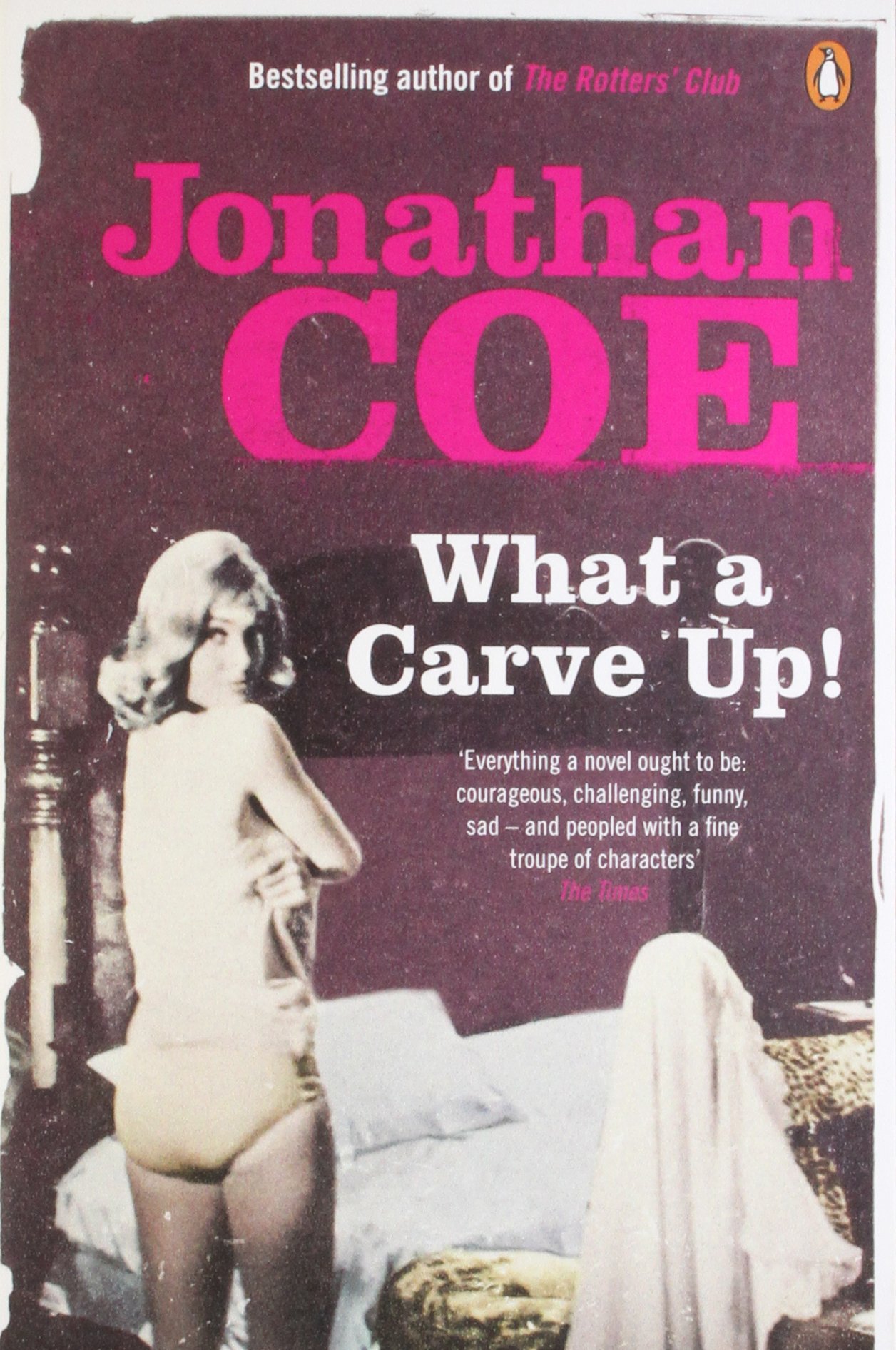

Now, it is crucial that Owen is a novelist rather than a film-maker. The distinction between film and narrative is one to which the novel is deeply wise. Although the sexual element in Pat Jackson’s 1961 film What a Carve Up!, obsessed over for decades by two of the novel’s central characters, is a crucial element of the novel (a still from the film is the cover image on several of its editions), the novel as a whole is sceptical of scopophilia. Obsession over sexual images in film is connected, via Owen and Thomas Winshaw, to physical and emotional impotence. By contrast, since the publisher attributes Owen’s failure to write sex to the very same impotencies, the novel as a whole is supportive of the publisher’s comments.

I would agree that there is an important distinction between sex on the page, on the one hand, and on screen or stage on the other. D.H. Lawrence, that pioneer of explicit literary depictions of sex, would have abhorred the adaptations of his novels, and classified actors’ acceptance of money in order to appear naked as literal and metaphorical prostitution. He may also have classified the interaction between them and an absent film audience as an ersatz connection bearing a similar relationship to the real physical encounter on which he placed such value as did First World War warfare to sincere hand-to-hand combat. Lawrence himself argues that the visual medium is intrinsically more shocking: ‘It is easy in literature […] You can get some of the lusciousness of Hetty Sorrell’s ‘sin’ [in George Eliot’s 1859 novel Adam Bede], and you can enjoy condemning her to penal servitude for life. You can thrill to Mr. Rochester’s passion [in Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre], and you can enjoy having his eyes burnt out. […] But in paint it is more difficult. You couldn’t paint Hetty Sorrell’s sin or Mr. Rochester’s passion without being really shocking.’ Here he implicitly admits why it is harder for a film adaptation to achieve the aims of Lady Chatterley’s Lover – to render sex as clean, natural, and unsensational – than the novel itself. Michael Owen’s description of the actor Shirley Eaton getting changed in What a Carve Up! adds an additional layer of modesty to that offered her by Kenneth Connor’s character (who tries not to look), and the film’s editor. When Thomas Winshaw, whose bank is investing in the film studio, tries to witness the filming of this scene, he and the reader are thwarted in seeing more than the film shows; but even had he succeeded we would still only have seen words.

Still from Pat Jackson’s 1961 film ‘What a Carve Up!’, starring Shirley Eaton and Kenneth Connor

Words are of course not unconnected to sex. Research suggests that women may be more aroused by ‘dirty’ talk than are men, and that they are more likely to read erotic fiction (such as the Fifty Shades series by E.L. James) than to watch pornographic films. They are more likely to masturbate to an imaginative range of mental scenarios, rather than merely to the thought of penetrative sex. Sex as created by the imagination from what is read, rather than impressed onto the mind by what is seen, may for this reason, to certain people, be more powerful.

Yet E.L. James is a case in point that writing which arouses may well not be of a high literary quality – that is, subtle, realistic, profound, or well-related to surrounding, non-sexual scenes (which is not to argue that the two modes are mutually exclusive). It is notoriously hard to write sex well. Michael Owen discovers this when, taking his editor’s advice, he sits down and tries to write a sex scene. He starts by writing a long list of words connected to sex – and, when this fails, cracks open a bottle of wine and tries to go for spontaneity. He desperately rotates alternative settings, clothes and adverbs. Finally he thinks:

Oh, to hell with it.

she was panting with desire

he was bursting from his pants

she was wet between the thighs

he was wet between the ears

she was just about to come

he didn’t know whether he was coming or going

But it is worth noting that what his editor had in fact said was: ‘there’s a crucial aspect of your characters’ experience which is simply not finding expression here’ [italics added]. That is not the same as a request for sexual explicitness.

Consider, for example, the Victorian novelists. They might be considered vulnerable to the editor’s charge; but that is only if they are read with an eye that sees only what is unavoidably recognised as sex. In fact, they excluded it from their novels no more than nineteenth century Russian literary critics, or Tudor playwrights, excluded contemporary politics from their works. They simply perforce did so in a veiled way, which we must recover the sensibility to discern.

For example: in George Eliot’s last novel, Daniel Deronda (1876), a recently-married couple is described getting dressed for an evening engagement:

“‘Oblige me by telling me your reason for not wearing the diamonds when I desire it,’ said Grandcourt. His eyes were still fixed upon her, and she felt her own eyes narrowing under them as if to shut out an entering pain.

Of what use was the rebellion within her? She could say nothing that would not hurt her worse than submission. […] She fancied that his eyes showed a delight in torturing her. […]

‘He delights in making the dogs and horses quail: that is half his pleasure in calling them his,’ she said to herself, as she opened the jewel-case with a shivering sensation. […]

‘You want some one to fasten them,’ he said, coming toward her.

She did not answer, but simply stood still, leaving him to take out the ornaments and fasten them as he would. […] Grandcourt inwardly observed that she answered to the rein.”

This passage tells us as much as we ever find out about this couple’s sex life – but it is enough for us to know that it is a sadistic one; the passage is heavy with cruel sexuality. To apprehend this, we have to be sensitive to suggestion, just as Victorian men were aroused at the sight of a woman’s instep, or as – one assumes – Taliban men are to see the same in Afghanistan today. Or as the film What a Carve Up! was found tremendously arousing by Owen and Winshaw in 1961, but would not be seen as such now; or as Lady Chatterley’s Lover was in the same year, when it was unbanned – but is now not seen as pushing any boundaries.

Restrained fiction, like restrained film, has a convention of skipping to after the act of sex – as Tolstoy does in Anna Karenina when:

“That which for Vronsky had been almost a whole year the one absorbing desire of his life, replacing all his old desires; that which for Anna had been an impossible, terrible, and even for that reason more entrancing dream of bliss, that desire had been fulfilled. He stood before her, pale, his lower jaw quivering, and besought her to be calm.”

Jonathan Coe does it too. When art student Phoebe is seduced by Roddy Winshaw, the narrative runs:

“‘I don’t think I should be doing this.’

But she did.

Roddy fell asleep soon afterwards.”

No more is needed, and Phoebe’s dignity is to a degree preserved.

However, though Owen’s editor is not an example, many British publishers from the 1960s onwards have put great pressure on their authors to write sex scenes in order to boost sales. Hilary Winshaw’s novel, to be published in 1990, contains ‘Sex every forty pages’. Three years later, the British literary magazine Literary Review founded the ‘Bad Sex Awards’ in order ‘to draw attention to the crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it.’ Winners have included Melvyn Bragg 1993, Sebastian Faulks, 1998, Tom Wolfe 2004, Norman Mailer 2007, and Ben Okri 2014. Last year’s winner was Erri De Luca.

To exemplify, here is Ben Okri’s winning passage, from The Age of Magic:

“When his hand brushed her nipple it tripped a switch and she came alight. He touched her belly and his hand seemed to burn through her. He lavished on her body indirect touches and bitter-sweet sensations flooded her brain. She became aware of places in her that could only have been concealed there by a god with a sense of humour.

Adrift on warm currents, no longer of this world, she became aware of him gliding into her. He loved her with gentleness and strength, stroking her neck, praising her face with his hands, till she was broken up and began a low rhythmic wail … The universe was in her and with each movement it unfolded to her. Somewhere in the night a stray rocket went off.”

Amusing though I find the endings to both of these paragraphs, I should say that I am sceptical of the Bad Sex Awards. Since individuals’ experience of sex is extremely varied, their likely reactions to literary depictions of it, and sense of what ‘bad’ sex writing is, is likely to be various too. At the annual awards ceremony in London, which I have attended on several occasions, the short-listed extracts are read out by actors, for laughs. The communal compulsion is to laugh at each one, but on several occasions I had no impulse to laugh, and sensed that the passage had been written in entirely good faith. There is also an undercurrent of hypocrisy in the fact that the award has brought huge publicity to Literary Review, because of the very fact – which the award sets out to disparage – that sex sells. Most of all, the award begs the question of what good sex writing would be, and whether it would not be more helpful to hold good sex awards.

Some writers have argued that it is easier to write sex well if the sex is unemotional; a good sex scene therefore may well not be good sex. My own inference is that one should stick to one or the other end of various spectra: objective and subjective; literal and metaphoric. One should stay focalised on one person or another, or remain external to both. And one should avoid cliché. Okri’s passage unhappily combines physical precision with some distracting metaphors.

I would add that it is advisable to stay away from taboo words. When read out at the Bad Sex Awards, they inevitably raise a laugh. Poor D.H. Lawrence had his gamekeeper Mellors use them abundantly in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, precisely because Mellors and he wanted to purge them, like sex itself, of their association with dirt. As Mervyn Griffith-Jones, Chief Prosecutor at the novel’s trial, said:

Members of the Jury, not only that type of background, but words – not doubt they will be said to be good old Anglo-Saxon four-letter words, and no doubt they are, but they appear again and again. These matters are not voiced normally in this Court, but when it forms the whole subject-matter of the prosecution, then we cannot avoid voicing them. The word ‘fuck’ or ‘fucking’ occurs no less than thirty times. I have added them up, but I do not guarantee to have added them all up. ‘Cunt’ fourteen times; ‘balls’ thirteen times; ‘shit’ and ‘arse’ six times apiece; ‘cock’ four times; ‘piss’ three times, and so on.

He goes on to quote:

“‘Beauty! What beauty! A sudden little flame of new awareness went through her. […] The unspeakable beauty to the touch of the warm, living buttocks! The life within life, the sheer warm, potent loveliness. And the strange weight of the balls between his legs!’ […] That again, I assume, you say is puritanical? Answer: It is puritanical in its reverence. I say: What! Reverence to the balls! Reverence to the weight of a man’s balls? Answer: Indeed, yes.”

This criticism of the novel and its defenders – and the titter which it is likely to have raised – indicated that Lawrence’s attempt to clean these words had by 1960 got nowhere, and it has got no further since. All cultures – not only the Anglo-Saxon ones that are particularly conflicted about sex, and which Lawrence was particularly addressing – persist in having taboo words which are associated with sex, excretion, or both. Lawrence’s ambition to change human culture and nature was too large. Even though the novel is now legal, there are strict limits on what of its language can appear on screen, especially television. The director with whom I worked on the latest, 2016 BBC1 adaptation of the novel, told me that at the BBC: ‘Currently fuck is strongly discouraged and cunt is unacceptable. They count number of uses and proximity to programme start. Every use of fuck would have to be approved at Controller level’.

Of course, the reason for this prohibition is that these words are usually used offensively. When they are not – as they are not by Mellors – they are likely to sound comic. The guidelines therefore inadvertently helped to save the novel from ridicule.

One of the best literary descriptions of sex I know is not from D.H. Lawrence, but Jonathan Coe. Michael Owen does not write it; he transcribes his dream of sex – perhaps suggesting something about Coe’s own authorial process, or his understanding of it. Owen’s dream is about being in bed with the girl he loves as a child, Susan Clement:

“the first thing I knew – almost fainting with the joy of it, the mazing, palpable reality – was that she was touching me, that I was touching her, that we were dovetailed, entangled, coiled like dreamy snakes. It seems that every part of my body was being touched by every part of her body, that from now on the entire world was to be apprehended only through touch, so that in the musty warmth of my bed, the curtained darkness of my bedroom, we could not but find ourselves starting to writhe gently, every movement, every tiny adjustment creating new waves of pleasure, until finally we were rocking back and forth, cradle-like, and then I couldn’t stand it any longer and had to stop.”

When, towards the end of the novel, he finally has sex – with a woman named Phoebe – he experiences it in the same dreamlike terms; although the abrupt ending does not happen:

“Their love was long, slow and sleepy, and although there were times when they did nothing but lie together, drowsily entwined, these intervals of huddled stillness were all part of a single movement, perpetual and effortless, during which they slid rhythmically in and out of sleep, rocked back and forth between dreaming and waking, and had no knowledge of the passing of time until Michael heard the grand-father clock in the hallways strike five, and turned his head to see Phoebe’s eyes smiling at him in the dark.”

Whatever one may think of porn, or literary porn in particular, I think that literature would be the poorer did it not contain such writing as this.