I have just reviewed Mud and Stars: Travels In Russia with Pushkin and Other Geniuses Of The Golden Age by Sara Wheeler. This literature-orientated travel book, in which Wheeler takes Russian writers from Pushkin to Chekhov as her guides to the modern country, prompts me to remember my own last literature-orientated trip to Russia.

The occasion was Lev Tolstoy’s 190th birthday, on 9th September 2018 (just two days before DH Lawrence’s 133rd; Lawrence was twenty-five when Tolstoy died in 1910).

I’d long wanted to go to Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s estate outside Tula, a city of half a million 110 miles South of Moscow. In a conference at Perm State University a few years earlier I had met Volodya – one of the relatively few male Anglicists working in Russian higher education. He is at Tula University, and invited me to this conference. Finally, here was my chance.

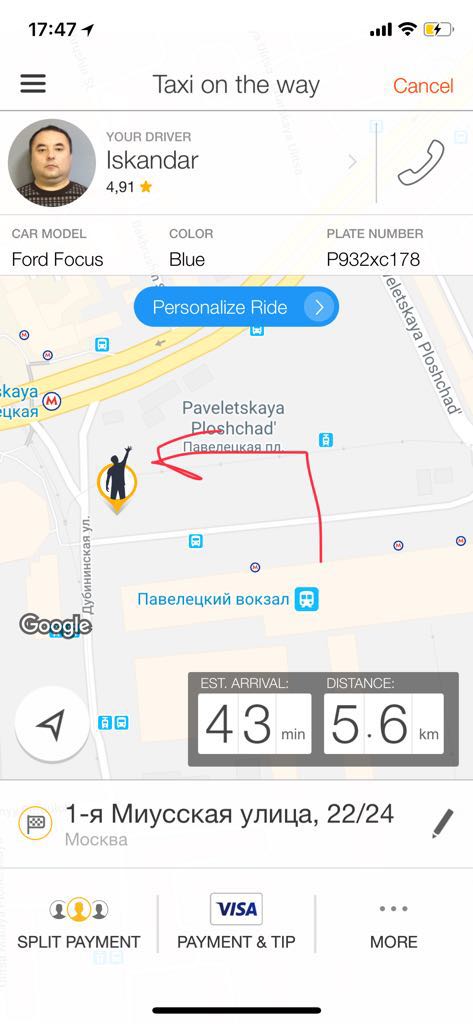

But I went via Moscow, because that’s where the flights go to and most of my friends are. I had one evening. I contacted both Misha and Sasha. Misha trained in law and works in television. He does not remember the Soviet Union. He said that I should come straight from Paveletsky Vokzal, where the direct train from Domodedovo Airport deposits one, to his workplace. In fact he would send me a taxi. He Whatsapped me with a map showing where Iksandar would pick me up.

So Iksandar and I joined the afternoon rush-hour. It had not occurred to Misha to tell me where he worked, nor me to ask. Ninety minutes later, we were still in the rush-hour. But what a route. Straight through Moscow, from South to North, past all the tourist sites, and straight into my history. In 2002 I had lived in Moscow, on the tenth floor of a dom on Prospekt Mira. I drank rather too much Baltika and had multiple friends called Pasha and taught English and read lots of Tolstoy. Moscow was rough and smoggy then. Capitalism had its gloves not just off but trampled underfoot in muddy snow. Nightclubs were postmodern meat-markets. Things have become softer since. But as I was driven through Moscow, my heart quickened. I realised again that it excites me just to exist in this country.

View from Iksandar’s taxi

Misha met me on the pavement and showed me to the offices of the production company where he works. His brother – a major television personality, it turns out – was there too, and said that he would join us later for dinner. Russians are very casual about meals. They can take them or leave them; there are no fixed times for them. I wanted a meal. Misha took me to the Georgian place nearby (it’s always a Georgian place in Moscow), and we caught up on the last several years. Then the brother arrived, and we all became slightly drunk, and I switched proportionately to Russian (it has ever been thus), and started talking about religion. A big van pulled up next to our pavement table and a black-uniformed man got out. The police? No, this was the brother’s car and his chauffeur. I invited the brothers to London. The answer to my question about religious belief went on for a long time.

At ten Sasha picked me up from Misha. He drives ridiculously fast, with one hand. But since Moscow has six-lane roads, it seems to work. In 2002 Sasha had been the only Russian patient enough with my embryonic Russian to speak to me, even to teach me (he had studied pedagogy in the Caucasus). He is also almost the only Russian I know who has done military service – between Afghanistan and Chechnya, though that didn’t stop him losing three comrades in two years (one to an accident, one to suicide, and one to bullying). During his basic training, he thought that he wouldn’t survive. When he had finished, he thought that he couldn’t survive the transition to civilian life. In the 1990s he tried to emigrate to Canada, but was refused as he didn’t have the required skills. Then he saw Brat II, and decided to stay and make his life work in Russia. He became, as he remains, a steel trader. The company that he works for used to be British-owned, but as a result of the sanctions it has become purely Russian (the British company still trades with it), and Sasha has become one of its co-owners – one of several perverse benefits of the sanctions to the economy. He lives in the South, so the centre of Moscow repeated itself. On the radio, Pavel Kashin’s ‘Life is Beautiful’ – a song I had never heard before, and which Sasha declared to be soppy (it is about an epiphanic walk through Moscow on an April day) – came on. This song became the theme tune of my visit.

The next day, after kasha (I was definitely going to have breakfast), Sasha drove me to Kursky Vokzal for my train to Tula. Again he drove with one hand, and again I was thrilled. The train (on which I obsessively listened to ‘Life is Beautiful’ on YouTube until I had run my phone imprudently low) was one of those many foreign trains which puts British ones to shame. It ran on time, it had screens for announcements and films, and I had room to cross my legs (my high thigh-to-calf ratio making this comfort a rarity).

Volodya met me at Tula Station.

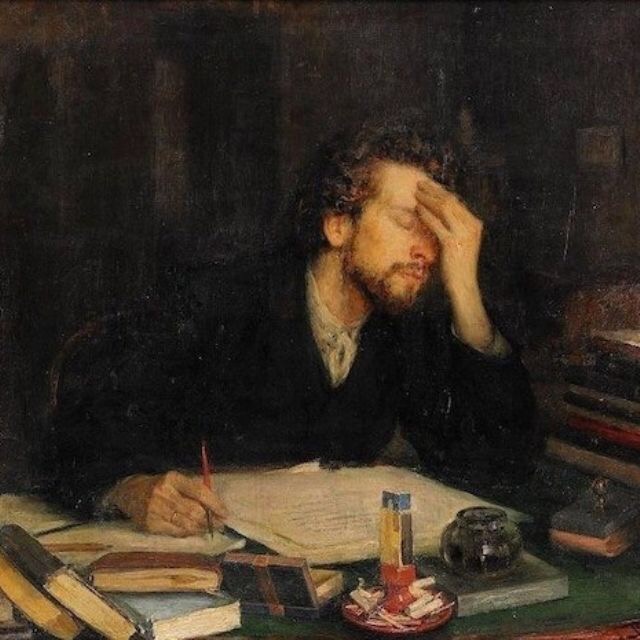

Suddenly I switched mode. I was no longer in wheeler-dealer Moscow, but in the company of an academic. Volodya, charmingly, has Leonid Pasternak’s The Pains of Composition as his WhatsApp profile picture.

The city was neat and sober in conformity with this change. We visited the Kremlin, and I tried and failed to take poignant pictures of the vast Lenin statue.

In the evening we went to a dramatization of Tolstoy’s The Devil by a famous Moscow director in typical modern Russian avant-garde style (Trevor Nunn complains that this style is over-dominant, and that his own text-based approach to Shakespeare is misunderstood whenever he directs in Russia). I’m afraid that I understood far from everything – but the theatre, as always in Russia, was a lovely white confection frequented by all ages.

The next day was the birthday. Part way between Tula and Yasnaya Polyana (about ten miles) Volodya said to me: ‘this is where Tolstoy’s estate started’. It is immense. No wonder Tolstoy spent the last third of his life trying to get rid of it, for all the opposition of his wife and several of his children. A village of the same name clusters at the estate’s gates. I couldn’t help but wonder if any of the inhabitants were illegitimate descendants via peasant lines.

This avenue of birches (the Russian tree second to none) forms the entrance.

It was a Keatsian appley September day. Gathered round the one wing of the house that Tolstoy did not gamble away in his Petersburg years, and in which he lived in his later years, were those who had gathered to celebrate his birthday. These were of many countries, and included a (legitimate) Tolstoy, now married to a local woman who curates the museum. A few speeches were given, including by several of Russia’s writers. I said a few words of my own.

Afterwards a journalist and cameraman from Kultura channel came to me to ask me to deliver my speech again; the lighting had been wrong, and they hadn’t managed to capture it. I fluffed this second rendition badly, with a giant camera poised dangerously close to eating my head.

The house was not large for such a family (thirteen children, of whom eight survived childhood).

What struck me was how often Tolstoy changed the location of his study. He wrote Anna Karenina in the room in which hung a portrait of his late brother (reincarnated as Nikolai in the novel), and on the couch of which his own body would one day be laid out and mourned over by hundreds of visiting friends and peasants.

He wrote War and Peace in a basement room, formerly a pantry, with meat hooks stuck in the ceiling. On the walls he hung his farming implements, so that – should the urge to do some scything suddenly come over him – he could rush out without any need to visit an intervening room.

He wrote his last works, including On Shakespeare and on Drama (the book on which I had come to give a paper at the academic conference attached to this celebration), in a small room next to his last, single, bedroom – so that he would not have to walk too far. In the study is the horse-hair sofa on which Tolstoy and several of his siblings and children were born.

In the bedroom were a pair of dumbells; Levin exercises with them vigorously in Anna Karenina when he is under spiritual strain.

It was from this bedroom that Tolstoy crept out on 28thOctober 1910, beginning the journey that would end in his death at Astapovo Railway Station on 7th November.

Outside the house was a bucket of flowers, from which we were encouraged to take one each to lay on the grave. In ones and twos we made our way through the woods to the glade where Tolstoy had decreed that he should be buried. His was the first secular funeral in Russia. According to his wishes there is no headstone, but the grave is visible, and honoured.

It is surrounded by orchards in which he planted some of the trees. I purloined three apples, and later in England gave one to my husband, one to my father, and one to a friend who had just been bereaved. Their flesh was rose red.

In the late afternoon (was this lunch? was this dinner?) came the conference feast. I found myself called upon to give another speech, and this time made up something in Russian. Several Indians were present, and a few Kazakhs. Somehow the food did not look appealing. There were bottles of champanskoe and of brandy; the sight of the latter made me feel sick. I was reminded of the overheated summer’s day dinner in Ian McEwan’s Atonement. I made the millionth resolution of my life to do as Tolstoy did, and shun alcohol. After dinner there were several activities on offer, including an art exhibition, and a lecture by a novelist from one of the Baltic states. I decided to make a token visit to the former and then retreat to my hotel room. Unfortunately the way to the art exhibition went through the lecture room, where I found myself eagerly invited onto the front row by one of the conference organisers. The language of this lecture, whichever it was (and I was too preoccupied by internal sensations to concentrate in any language), needed to be translated into Russian every few sentences, doubling the length of delivery. At the end I rushed first for a toilet, and then for my hotel, where I decided that I was freezing and needed a sauna. This was possible; the hotel had a banya, and I asked for it to be turned on. I have since learned that the last thing you should do if you are running a temperature is to visit a banya. But that is what I did, with the giant complex to myself. Then I entered into a long dark night of toilet trips, and hot showers, and shivering.

I was due to give my paper at Tula University in the morning. I called Volodya at eight and said that I didn’t think I could make it. He came straight round, and organised a switch with someone who was due to present the following morning; this gave me twenty-four hours to recover. Slightly nonplussed by my veganism, he brought me corn rusks and water bottles. And a thermometer. And – when my temperature rose steeply in the late afternoon – a doctor. I was interested to see what this would be like, not being too ill to enjoy the indulgence of a doctor being called to my bedside. The doctor turned out to be female, and she was accompanied by a male nurse. She was jolly and amused and brisk and kind. Volodya translated as necessary. Later that day, Volodya was to tell me the story of having accompanied some Russians to America, one of whom was hospitalised. Volodya had to translate every request for permission to touch a certain place, to raise a t-shirt two inches, and so on; each permission had to be signed for. In Russia, it turns out, examinations are rather more efficient. The doctor needed to listen to my heart-beat, so up came my nightie to my chin; Volodya averted his head as quickly as possible. I was pronounced ‘khudinkaya’ (thin) on account of my veganism (the doctor was not thin, but then again nor was I). I was informed that, since I had fallen ill at a state event (Tolstoy’s banquet), I had the right to free hospitalisation. This I waived. I was given a course of antibiotics and pronounced fit to fly home the following day, if my temperature didn’t rise again. I hadn’t signed a single piece of paper.

My temperature didn’t rise again, and the following morning I wobbled out of bed. Volodya took me and my suitcase (stuffed with the Tula specialties which Misha – who is from Tula – had commissioned one of his friends to deliver to the hotel) to the University. The lecture hall was large, the stage high, the lectern tall, and the audience serious. My talk wasn’t one I was sure about; it seemed churlish, especially as a foreigner, to discuss a problematic work of Tolstoy’s (On Shakespeare and on Drama is very problematic, and so is saying anything helpful about it). I was following a Russian who knew vastly more than me, and who was speaking warmly about less problematic works. Like the Balt two days before, I was translated every few sentences. Towards the end of my talk, I developed three needs simultaneously and strongly: to faint, to excrete, and to be sick. Perhaps each need counter-balanced the other. In any case, I dug my nails into my palms, sped up my speaking, and made it off the stage without running. A few academics expressed appreciation; I needed it.

Half an hour later I was on the minibus for Domodedovo (this is like going straight from Brighton to Gatwick rather than via London). The road goes straight through a hundred miles of trees. I clutched at my antibiotics, which are not licensed in the UK, but which were the right ones for all that.

For the next few weeks, I was in a haze of love for Russia. It had broken me down physically, and I had risen from the ashes. I had a fridge magnet from Yasnaya Polyana, and a thermometer from Volodya. I am still eating Misha’s Tula preserves. Life is beautiful.