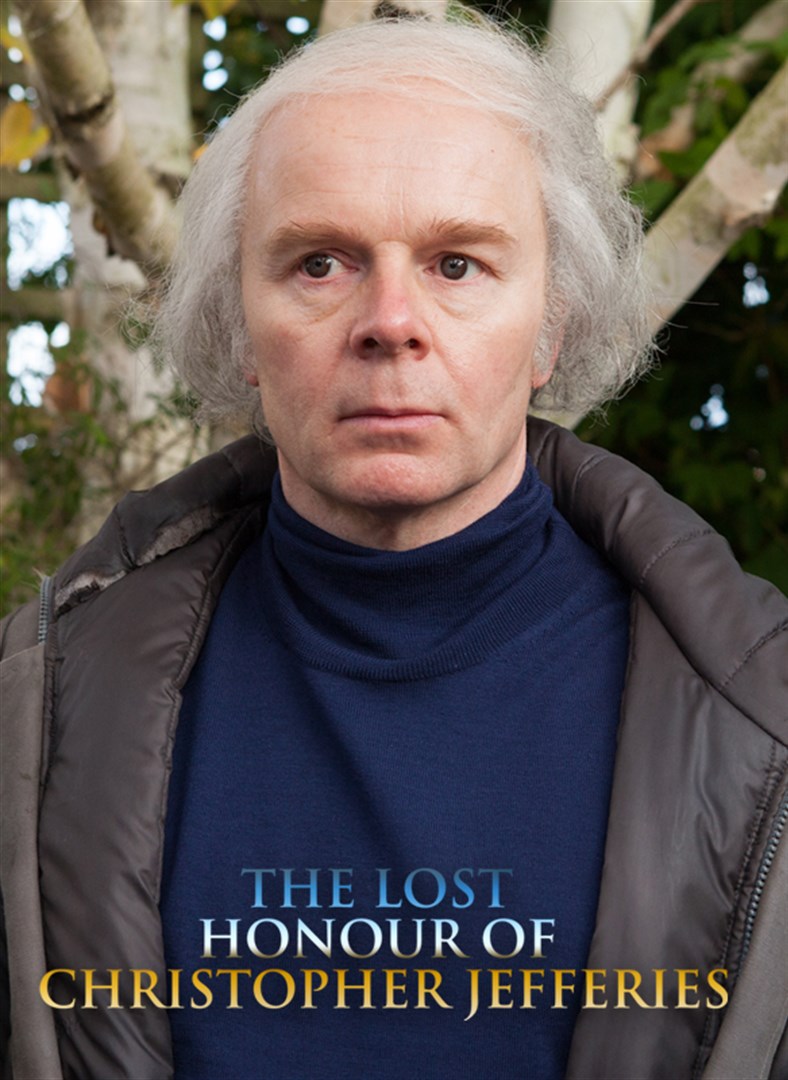

The title plays on Die Verlohrene Ehre von Katherina Blum (The Lost Honour of Katherina Blum), Heinrich Böll’s 1974 novel about a woman whose life is destroyed by an intrusive press reporter working for a lightly-fictionalised version of Bild.

Christopher Jefferies is the retired secondary school English teacher who four years ago this December was arrested in relation to the murder of his tenant, the twenty-five year-old landscape architect Joanna Yeates.

He was held at a police station for forty-eight hours for interrogation, before being released on bail.

He then discovered that several of the country’s most widely-read newspapers had assumed and proclaimed his guilt, in connection with a history (allegedly apparent throughout his long teaching career) of sexual perversion.

Soon afterwards another of Jefferies’s tenants, the young Dutchman Vincent Tabak, was arrested for the murder of Yeates, and in May he confessed to her manslaughter. In October 2011 he was found guilty of murder.

Jefferies had several close friends, including former pupils, who supported him through this period, and urged him to sue the newspapers concerned. Initially reluctant, he did so. Eight newspapers settled with him out of court.

Since then he has become a campaigner for Hacked Off, the campaign group advocating the implementation of the recommendations of the 2012 Leveson Report.

A drama focusing on Jefferies has one obvious ethical problem. Its centre is a man ‘monstered’ (as the phrase now has it) by the tabloid press, placing at the periphery a woman who was strangled.

The film has the moral intelligence to be keenly aware of this. At its close, Yeates’s boyfriend plants a herb garden in her memory. Titles summarising Jefferies’s subsequent life are superimposed on this background – holding both in relation, and making Yeates’s death the contextualising reality of Jefferies’s further life.

Tabak (played with haunting geniality by Joe Sims) is treated humanely. His possible motivations and degree of guilt are speculated upon; a film of this kind could easily have had him at its centre instead.

Whatever the murder’s nature, however, the film suggests that it was probably of a kind from which society can only do a limited amount to protect itself.

It argues that society can and should, however, protect itself from press behaviour of the kind which affected Jefferies. That is its implicit justification for placing Jefferies, not Yeates, at its centre.

I watched the preview with little prior knowledge of the case. Not tending to read either the newspapers which were principally involved, or stories about murders, the names were unfamiliar to me. This was an advantage (of which I am hereby, I confess, depriving you); I saw Yeates and Tabak on their first appearances with no frisson of anticipation, just as Jefferies, or they themselves, would have seen each other at the time.

I was hugely impressed and moved.

Jefferies is memorably played by Jason Watkins, who spent time with Jefferies in order to learn his mannerisms. The similarity in their physical appearance is fortuitous and remarkable.

The film will appeal particularly to people who have something in common with Jefferies: academic, cultured, conscientious, pedantic, Guardian-reading, civic-minded, Church-going. The soundtrack consists of the kind of Classical music which Jefferies himself would enjoy.

It is a study in English eccentricity. As one of the characters observes, the English are usually good at accommodating, if not celebrating, eccentricity. In this case they failed. Being an unmarried retired man with hair combed over a bald patch and a school-masterly manner were enough, in his case, to make it plausible that he was a paedophile and the murderer of a contrastingly normal, attractive, young woman. The Common Law principles of innocence until proven guilt and of sub judice were lost, for much of the British press and public, along with the phrase which the British press used to use in such situations: ‘a man in his sixties is helping the police with their inquiries’. Had Jefferies been charged, he could only with difficulty have had a fair trial.

On his release from custody, a rather oppressively-normal friend mocks him into changing his appearance such that the accusations against him would diminish in plausability. In a memorable barber-shop scene, his hair is cut short and tinted to its original sandy colour. The contradiction that combing hair horizonally is perceived as risible artifice whereas tinting is not is neither explicitly acknowledged nor denied by the film (though in fact in modern society both are condemned for men, in unjustifiable distinction to women).

The dialogue was carefully researched. Morgan initially wrote the interrogation scenes himself, but when Jefferies pointed out how far they diverged from reality, Morgan used the police transcripts verbatim instead.

Only towards the end of the film, when the Hacked Off agenda becomes more prominent, does the dialogue occasionally beocme wooden, and the film’s tension and energy lapse. They are recovered, however, by the end. Moments of warm comedy sparkle throughout.

Given the kind of retiring person that Jefferies was before his tenant was murdered, it is extraordinary that he collaborated with this film. But he did so for the same reason that he joined Hacked Off. He is now a campaigner – and the film shows his transformation.

He is not sufficiently transformed, however, as to have wished to attend the screening.

Instead, from the South of France, he sent a two-minute film voicing support for the film and Hacked Off.

I urge you to see it.