Below is the pre-edited version of a review which appeared in Literary Review, September 2014, pp. 8-10.

The Poems: D.H. Lawrence, ed. Christopher Pollnitz (Cambridge University Press, 2013, 2 vols, 1391pp, £130)

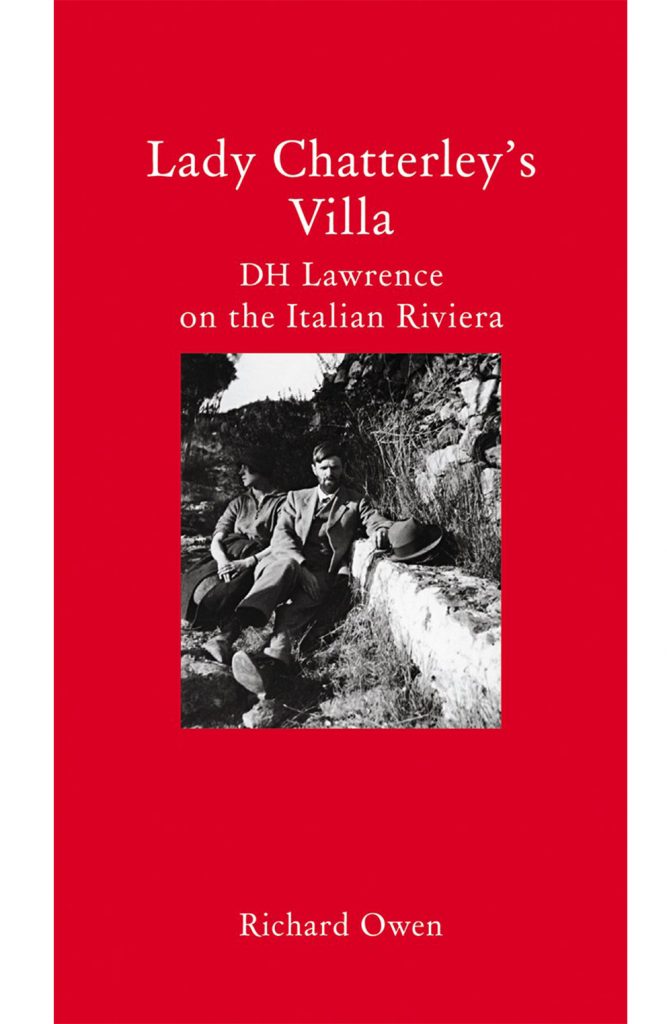

Lady Chatterley’s Villa: D.H. Lawrence on the Italian Riviera, Richard Owen (Haus, 2014, 226pp, £12.99)

At last things are looking up a bit for D.H. Lawrence. Four decades after the Second Wave feminist critique brought his reputation crashing down from its dizzy 1960s heights, today’s students come to him as though to a blank sheet. If they don’t know much about him, at least they know no ill of him. Critics are making a counter-case for Lawrence as a feminist, as did the 2011 BBC4 adaptation of Women in Love. BBC1 is adapting Lady Chatterley’s Lover. And the forty-seven volume Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D.H. Lawrence, ongoing since 1979, is finally almost finished, making Lawrence the most meticulously-edited writer of the early twentieth century.

I say almost finished. This is because the two volumes of his Poems (one of the poems and prefaces, one of editorial introduction and notes) are still to be joined by a third volume of textual variants and unpublished poems.

But these volumes are worth celebrating as they stand, for presenting 860 poems in as close a form and order to the last one Lawrence chose as twenty years of meticulous editing could establish. Pollnitz’s achievement is immense.

The editorial principle has major implications – notably, that the shape of four of Lawrence’s early collections are lost to his selection for ‘Rhyming Poems’ in the 1928 Collected Poems. This makes sense. Lawrence had to bow more to editorial pressure in his earlier collections than in that of 1928, when he also made revisions as a more experienced poet. Those who miss the ‘album’ feeling of the earlier collections could buy a relevant first edition for no more than the CUP Poems. It should be confessed that Lawrence would have blanched at his work costing £130. He cared about accessibility. But he also cared about production values. If he didn’t like luxurious, he didn’t like cheap, and is likely to have approved of the CUP volumes’ sober high quality. In any case, CUP intends to release the Lawrence series in cheaper formats, including electronic.

The current Volume II itself resembles a PC rather than an iPad: the scholarly apparatus lets you do pretty much whatever you want with it – but you need to know your way around. Textual technophobes can stick mainly to Volume I: a fine reading copy.

Even they, though, should read the 135-page essay describing the composition, publication, and reception of each of the collections. Here Pollnitz shows how the poems fitted in with Lawrence’s other writing and living. His relentless travelling massively complicated the process of securing publishers for, and editing proofs of, poems which were for the most part in any case published in both England and America. The 1929 Pansies had a particularly fraught passage: a typescript was impounded by the UK authorities, found indecent, and destroyed – after which Lawrence gave a replacement copy to a friend to post from Nice, rather than posting himself from Bandol. We get the sense of Lawrence as a careful businessman (he needed to be), who worked hard and fast, meticulously reworked his poems, and treated adverse criticism – particularly on the grounds of obscenity – with exuberant scorn, sometimes in poetic form.

It’s fitting that the culmination of the Cambridge Lawrence should be the poems. He was a poet all his writing life, from 1905 to his dying days, when he was still dealing with proofs of his late, stinging Nettles (1930). The poems also encompass a range of techniques and emotions greater even than is found in his prose. Verses free and unfree express delighted desire, righteous rage, satyric glee, fear of death, need of God, and an astonishing ability to empathise with the orgasm of tortoises. In his Foreword to Pansies he explains that his ‘pensées’ are ‘casual thoughts that are true while they are true and irrelevant when the mood and circumstance changes’, as ‘A flower passes’, ‘one eternal moment easily contradicting the next eternal moment.’ Few contemporary critics were as perceptive. Here Lawrence rejects the high modernist commitments to impersonality, implicature, and creating well-wrought urns – flinging down his pensées, one after the other, and giving us the sense of living with him his pained, throbbingly perceptive life.

If one senses that Pollnitz had to fight long and hard for the texts he serves up to us, one senses that the former Times correspondent Richard Owen was handed a big gift on a plate when Anthea Secker, daughter-in-law of Lawrence’s publisher, showed him the unpublished papers of Martin Secker’s Italian wife (Cate)Rina. It’s clear that Owen, like Lawrence, has his own love-affair with Italy, and that he entered with a will into reconstructing the story which this correspondence tells. He sketches engagingly Lawrence and Frieda’s arrival in Italy in 1912, their periods in Sicily, and their stay near Florence in 1926-28 during which Lawrence wrote Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But the narrative pace slows for the six months of 1925-26 which they spent in Spotorno, the Riviera resort where Rina’s parents ran a hotel. Rina visited them regularly, and described in letters to her husband how their strife intensified once Frieda’s daughters and Lawrence’s sister had arrived to visit. After the sister and Frieda established that they ‘hated’ each other, Lawrence left for seven weeks, during which time Frieda may have started her relationship with her future husband, their landlord Ravagli.

Much of this story is already known, and Owen wisely doesn’t rely on Rina’s account alone, but on Lawrence’s, Frieda’s, and Ravagli’s amongst others. But it’s useful to have existing perspectives confirmed and nuanced, and interesting that Rina mentions nothing of Frieda’s connection to Ravagli; biographers’ guesses at the date of the beginning of their affair vary between 1926 and 1928. Of most interest is the sense one gains of the woman who almost certainly inspired Lawrence’s story ‘Sun’. Here a New Yorker cures her neurasthenia by sunbathing naked with her toddler in Italy. The sun penetrates her deeply, and she nearly has an affair with a peasant too, before returning to the New York husband who arrives – grey, but dazzled – to visit. Post-natally depressed Rina sunbathed at Spotorno with her son Adrian. Her English husband had the good grace to publish the story.

Owen also offers measured support for Frieda’s claim that Rina was Connie in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He points out that the novel is an extension of both ‘Sun’ and The Virgin and the Gypsy (the latter also written at Spotorno), in that a higher class woman not only has sex with a working-class man, but wants to live with him for the rest of her life. Frieda, making her claim about Rina, may have wished to deflect attention from her own obvious resemblance to Connie – an aristocrat married to a man of lowered sexual potency whilst drawn to a man of a lower class. Yet the retiring, pining Connie far more resembles Rina than does the combative, deeply-non-depressive Frieda. Owen also speculates persuasively that Lucy Lamont, an older woman with whom Martin Secker had a connection that irritated Rina, may have inspired Ivy Bolton, Clifford’s nurse, who irritates Connie.

Owen offers an engaging picture of the Italian Riviera as colonised by the English (and their churches, clubs, and libraries) between the Wars. His book is in part a travel guide to the Italy of Lawrence’s time and our own. He doesn’t go as far as Geoff Dyer, whose (credited) Out of Sheer Rage is an autobiography of Lawrencian pilgrimage, but one does sense his delight in the food and the views he experienced whilst researching. Even the format of the book, red and hardback like the Cambridge Lawrence, but unlike it capable of fitting into a large pocket, recalls the Baedeker guides with which the Lawrences travelled – right down to the red ribbon. One can imagine taking it on a trek of Italy’s Vias David Herbert Lawrence.

The disappointment of the book is Rina. Owen himself makes no great claims for her; she is his book’s raison d’être, but he does not hide his puzzlement that she never visited the Lawrences after they left Spotorno, despite repeated and urgent invitations. One infers that Lawrence was right in calling her ‘very nervosa’. She certainly lacked the sensuous unconsciousness which drew Lawrence to Italians; hence her literary projection as a New Yorker. But Owen is kind to all his subjects – most of all to Lawrence, whose death and hope of eternal life are tenderly described. He ends his book, centred on three works about sexually-alive women, by suggesting: ‘Perhaps it is time to reassess D.H. Lawrence – as a feminist.’ It certainly is.