I marched yesterday for two reasons.

First, because I consider a second referendum a democratically-necessary concomitant of the first one. The latter totalled on one side the votes of all those who envisioned multiple mutually-incompatible versions of a post-Brexit Britain (51st US State, Singapore of Europe, Canada of Europe, second Switzerland of Europe, second Norway of Europe, Britain heart of the Commonwealth, little England, and so on). It cannot be assumed with anything approaching the degree of confidence appropriate to such a decision that everyone who voted for any one of these visions would prefer any given Brexit over remaining in the EU. One can argue over other things – over whether or not sixteen and seventeen-year-olds should have been allowed to vote, whether or not it was right to exclude from the original referendum both EU citizens living in the UK and UK citizens living in the EU, whether or not a super-majority should have been required, and what the level of obligation on government and Parliament to implement the results of what was technically, but not advertised as, an advisory referendum should be. But one cannot, I think, dispute the soundness of the first point. The original referendum was not between two clear alternatives, but between one clear alternative and a radical unknown. On most issues, when given a choice ‘between the status quo and something else’, most people would vote for the latter. When given a choice ‘between the status quo and something unclear in its details but delimited in its outline’ the proportion of those voting for the latter is inevitably diminished. A second referendum (the term ‘People’s Vote’ is propaganda so I shall leave it alone) should be run with the clarity that the last one lacked regarding its power in relation to Parliament. It may or may not be won by ‘remain’.

This last point is poignant in relation to yesterday’s marchers, whom I assume to a woman and man to support ‘remain’. But my second reason for marching was that I share many of their ideals and their ideas, and would strongly prefer the UK to remain in the European Union than for it to leave under any circumstances.

I am, I imagine, more critical of the EU than many of them. I can’t be the wife of a Greek and not feel the counter-productive and cruel injustice of the ECB’s treatment of Greece in particular amongst South-EU countries. I can’t be an anti-Russophobe and not be sharply critical of the EU’s cold-shouldering of Russia in the immediate post-Soviet period when it approached it about joining, nor its collaboration with NATO as its stalking horse in Eastern Europe, where – amongst other horrors – CIA black sites for torture have proliferated. I can’t have a brother-in-law who works as a doorman at a refugee camp in Athens and not be aware of the cruelties and inefficiencies with regard to the treatment of refugees in and outside ‘Fortress Europe’. I can’t be vegan and not desperately disappointed in the EU animal welfare standards which – as is not the case in human rights – stretch to accommodate the worst violations of its member states, such as the production of luxury foodstuffs through the torture of geese and calves in France, and the ritual twenty-minute torture of bulls in Spain. I can’t come from Grantham in Lincolnshire and not understand the cultural fears and resentments that arise in economically-deprived and ethnically-homogenous communities which absorb large numbers of foreigners in a short period. I note with serious interest the fact that a good half of those people, whom I greatly admire, with whom I make common cause against American imperialism, against Russophobia, and in support of Assange, Manning and Snowden, support ‘leave’. Their reasons for wishing to leave are doubtless related to some of the points mentioned above, and are in many cases aligned with a left-wing critique of what they see as a capitalist behemoth – to the right rather than to the left of the populaces of its countries severally. I support some of the leaver and remainer critiques of the ‘remain’ campaign, including all those voiced in this article. Some of the moral and strategic failings of that campaign have reflected shortcomings which belong to the EU itself. There is an adoration of the EU, visible and palpable on yesterday’s march, which venerates less the entire reality of the EU than what it represents at its best – international peace, intercultural understanding, and the benefits to all concerned that may come from freedom of movement. The assumption that Brexiteers are perforce opposed to all of these things is incorrect. A few of the criticisms that I speculate that D.H. Lawrence would have had of the EU, I share.

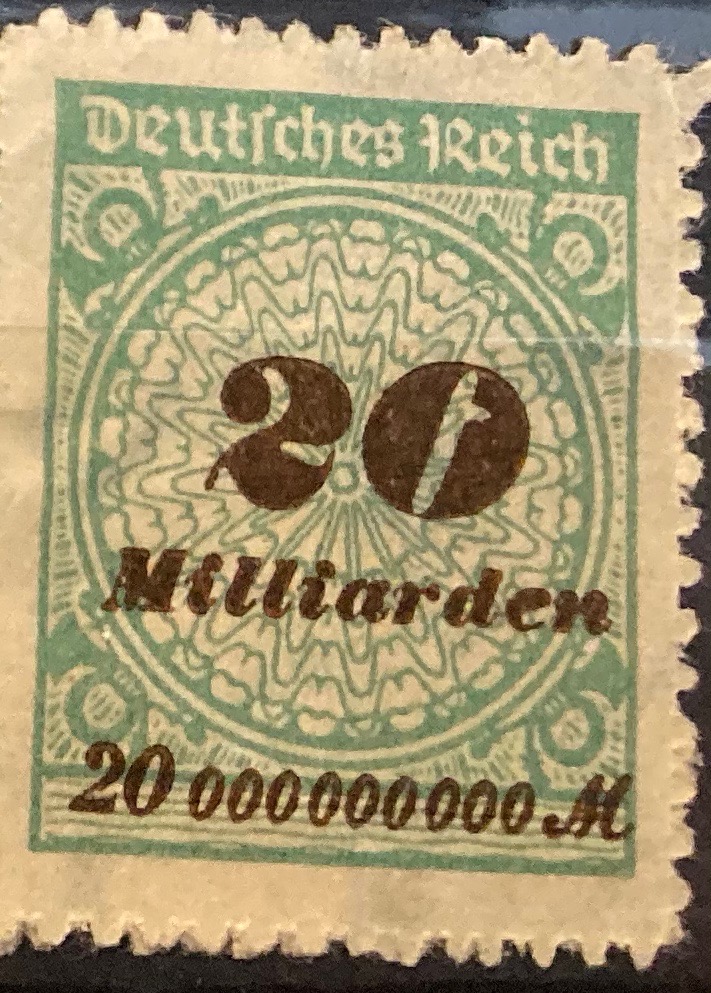

But no left-wing critic of the EU should be able to ignore the obvious fact that the leading Brexiteers are disaster capitalists – individuals who have much to gain personally from a hard Brexit and from the alignment of the UK and its health service with the interests of US companies. A Brexited Britain in the future under, let us say, a Jeremy Corbyn government, would still have to deal with the economic fallout from any deals that a Conservative government had previously signed with US companies, and from the disruption caused by Brexit itself, which is likely to cause suffering to those least able to bear it whatever the attempts of a cash-depleted Labour government to mitigate it. No anti-Russophobe critic of the EU should overlook the fact that both parties in the US are dominated by fervent Russophobes and that a Britain outside the EU will inevitably align its foreign policy more closely to its biggest ally; whereas within the EU are strong and increasingly-vocal groups whose economics interests are suffering because of the anti-Russian sanctions that have been imposed on them by the US, and from which a more confident and independent EU might free itself, thus forming a more peaceful and productive relationship with its Eastern neighbour. Nor should the anti-Russophobe critic overlook the fact that – contrary to the claims of some remainers and some Brexiteers – Putin has said not a word in support of Brexit, but on the contrary says that he values a stable EU, since this is Russia’s biggest trading partner. On the in-many-ways damaging Common Agricultural Policy, on animal rights and welfare, on the treatment of Southern Europe – on all of these things the EU can become a better version of itself. I fear that outside Europe, the UK, or whatever of it that is left (the recent dismissal of Loyalist interests by the UK government is worthy of censure no matter the level of one’s support of the Irish Republican cause), will either become a worse version of itself, or will ask for re-admittance a few years down the line after huge wastage of tears and treasure. As for the EU itself falling apart after Brexit – all the signs so far are that it has galvanised the Union. Grexit sentiment – in terms of leaving the EU as opposed to leaving the Euro – is all but non-existent.

Finally, being young for my generation, I didn’t just have a grandfather who fought in the Second World War, but two uncles who were then teenagers. One of them, my dear Uncle Ted, died one week ago. The other, my dear Onkel Wilfried, lives still in my mother’s home town of Alzey, Rheinhessen. My parents’ marriage represents that burying of wartime hatreds, rejection of ethnic exclusivity and cultural insularity, and promise of international peace, which provided so much impetus to the development of the EEC and EU, and which, for all its obvious but remediable faults, continue to animate the latter. That the Liberal leader Jo Swinson has risked a no-deal Brexit by her refusal to back Jeremy Corbyn as a caretaker Prime Minster in charge of averting this possibility is a scandal that tarnishes the name of Remain. But with the best impulses of the Remainers and of the European Union I stand, and it is in their honour that I reproduce the photos I took yesterday.