Russia doesn’t do towns. There are no Russian Granthams, Great Yarmouths, or Leighton Buzzards. Its vastness prohibits such chirpy, middling, interconnected entities. Instead, its farmers live in villages whilst everyone else huddles in metropolises. Despite the unlimited, dirt-cheap land across which they might spread themselves, the Russians pile in their hundreds of thousands in tower blocks, like stakes in a metal paling guarding an older, wooden centre and its kremlin from the near-empty expanses near-infinitely around.

For all their apparent isolated independence, these cities have an undisputed tsar: Maskvà. Since it replaced Kiev as the capital of the Russians in the thirteenth century, Moscow has directed the expansion of its people. Most of Russia’s cities owe their existence to it, and all remain culturally, politically and economically subordinate to it. In the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Moscow was metonymic of Russia, and symbolic of dictatorial rule.

Yet there was an interlude. After Peter I trumped Louis XIV’s moving of his court to a new palace fourteen miles outside Paris, by moving his court to a new capital four hundred and fifty miles outside Moscow, the latter city was left behind. Sankt Peterburg, as young as New York and more ambitious, represented Germany, Europe, neoclassicism, modernity, multiculturalism, multilingualism, the military, money, and the Petrine aristocracy. Moscow became a backwater, whilst remaining the home of Russia’s oldest families, kremlin, churches, monasteries, and beliefs. It was Russian; St Petersburg was cosmopolitan. St Petersburg was the head; Moscow was the heart. St Petersburg had been built with forced labour in a cold swamp where no metropolis had any business to exist; Moscow had developed organically over centuries.

No wonder that Russia’s conservative-patriotic nineteenth-century novelists gave St Petersburg a bad rap (slum-riddled and psychically-threatening in Dostoevsky; corruptly glamorous, frivolous and faithless in Tolstoy). How different Moscow’s reputation in those two demoted centuries to what it had been and would become. It was quiet, pacific, of ontological rather than pragmatic importance. When Napoleon came and – according to Tolstoy – looked down on Moscow from the hills South of the city, he saw it as a woman waiting to be raped:

At ten o’clock on the 2nd of September the morning light was full of the beauty of fairyland. From Poklonny Hill Moscow lay stretching wide below with her river, her gardens, and her churches, and seemed to be living a life of her own, her cupolas twinkling like stars in the sunlight.

At the sight of the strange town, with its new forms of unfamiliar architecture, Napoleon felt something of that envious and uneasy curiosity that men feel at the sight of the aspects of a strange life, knowing nothing of them. […] Every Russian gazing at Moscow feels she is the mother; every foreigner gazing at her, and ignorant of her significance as the mother city, must be aware of the feminine character of the town, and Napoleon felt it. This Asiatic city with the innumerable churches, Moscow the holy. Here it is at last, the famous city! It was high time.

[War and Peace, trans. Constance Garnett]

The mother was soon to be burnt by its own inhabitants in their tactical retreat from the French army. The rebuilt ‘old’ Moscow that the nineteenth-century writers knew was architecturally younger than St Petersburg. Yet its place in the body of the country remained unchanged. Romanticism projected through the Russian prism gave Moscow the aspect of antiquity, and its ‘Soul’ the aspect of mysterious profundity. When Alexander II was assassinated by anarchists in 1881, the Church of the Spilt Blood on the bloody spot in St Petersburg imitated Red Square’s St Basil’s, in order to assert Russianness in the face of Western ideologies that inspired murder.

St Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow (1561)

The Church of the Saviour on the Blood, St Petersburg (1883-1907)

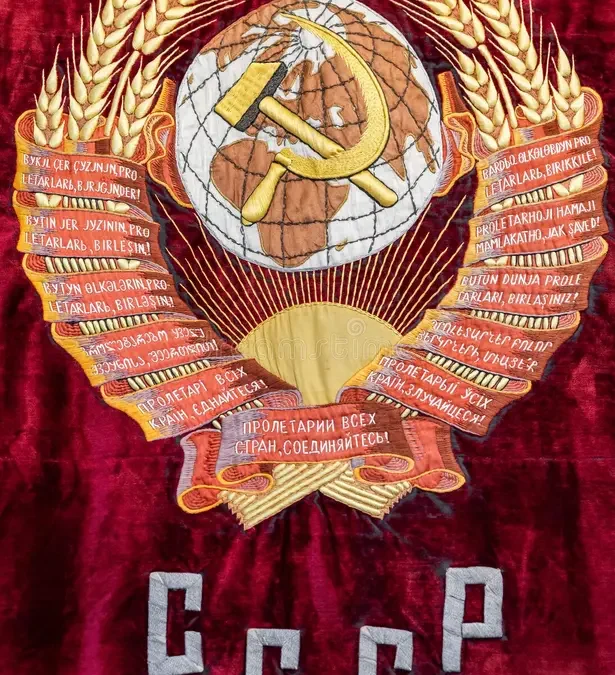

Yet after the Revolution had exploded in, and renamed, St Petersburg, Moscow became the world’s capital of an internationalist ideology written by a German. It simultaneously reinvented the autocracy for which nineteenth-century Russia had been notorious, whilst St Petersburg in its turn sank into a backwater, its hypnotising neoclassical facades slowly decaying, its pace of life gradually slowing. It was gripped by a sudden nine hundred days of pain during the Second World War; then the process resumed. The very historicism with which the tsarist summer palaces, destroyed by the retreating Germans, were respectfully reconstructed, confirmed the city’s place in the past.

Soviet Communism was directed from and exemplified by Moscow. There the metro was at its oldest, deepest, and most chandeliered; the Terror claimed the most victims; the Lyubyanka tortured the most people; education was the best; living standards were the highest. It is a little-known fact, though recorded by the novelist Mikhail Bulgakov, that the devil and his retinue visited Moscow in 1937; but the Communists, being rationalists, have always denied this.

The Ostankinskaya television and radio tower broadcast the Communist message to all in the world who – to absorb or fight it – would listen. East Berlin’s Fernseherturm, huge though it was, was only two thirds of the height and a fraction of the authority of the Ostankinskaya needle, from which it took its message.

Moscow remained the promised land for Russians: a hugely exciting place to visit, and highly desirable place to live, but for many – as for Chekhov’s three sisters – hard to get to; distant; unaffordable; requiring a permit; a once-in-a-lifetime place for a holiday. Most people knew two metropolises: the one they lived in, and a semi-mythologised Moscow.

Then came the collapse. Communism crashed and Goldman Sachs arrived. Capitalism rocked up with its gloves decidedly off. Western products and ideologies sold for many times the Western price. Western cars arrived, with native oligarchs and minigarchs to drive or be driven in them. Anti-Western Communist propaganda had never rung truer than when it was silenced. The death rate soared. The birth rate collapsed. Unemployment exploded, especially for women, who starved themselves into attractiveness to potential foreign husbands or paying johns. Food markets were taken over by Caucasian gangsters. Literally legless Afghan vets dragged their torsos around on skateboards to beg. Professional musicians busked in subways. Professional ballerinas stripped in nightclubs.

Moscow became the inter-war Weimar of the nineties and early naughties: devastated, exhilarated, febrile, unstable, unequal, racy. Its nightclubs popped up and popped down, with feis-control to select sexy women and rich men, paid dwarfs in leopard-print thongs, male and female strippers, girls from the provinces looking for loaded lovers, semi-lit unisex toilets, strenuous imitation of a pornographically-imagined West. Western men discovered that sex was on tap, and would stay for a few years before – as novelist A.D. Miller put it – ‘they retreated to service more reputable crooks in London or New York, sometimes as a partner in Shyster and Shyster or wherever, taking with them a handy offshore bank balance and some tits-and-Kalashnikov Wild East stories to console their live-long commutes’.

Then, mercifully, the post-Soviet period became the post-post-Soviet one. Capitalism found its gloves and put them back on. A younger generation of musicians found its way back into the Bolshoi, and the ballerinas dropped their second jobs as strippers. The business culture and night-clubs became more civilized and less inter-connected. Middle-aged men no longer drank themselves to death out of heartbreak as once they did, nor are ‘snowdrops’ – frozen corpses – discovered in each spring’s snowmelt as once they were. The birth rate and life expectancy have risen every year in this millennium. Beggars are not visible in Moscow any more.

Moscow is no longer a cipher for anything. Despite recent Western attempts to generate a phoney neo-McCarthyism, it is now a complex, not a simple, signifier. It no longer represents Orthodoxy, autocracy, serfdom, Communism, ‘diky’ (wild) capitalism, or any other single or simple ideology or phenomenon, either in Russia or the world at large. Its government is rightly complained at in the regions for not lifting provincial living standards faster closer to its own, and for not allowing the regions more power. Yet Moscow itself is still loved, in simple and unsimple ways.

Red Square remains a place of national pilgrimage. The Alexander Garden on the Kremlin’s West wall is still the place where the country’s couples want to kiss, and Gorky Park is still where the country wants to ice-skate. The Sparrow Hills remain a place from which to gaze at the city on arrival (like Napoleon), or departure (like Bulgakov’s Satan and his retinue).

Moscow is at the heart of ‘European Russia’. It had to be located in the West of the country for the same reason that Washington had to lie in the East of the US; ethnic Russians are Europeans who spread East, just as European Americans, largely at the same time, spread West. But Russians refer to Europe as somewhere else, and it is fitting that Moscow does not lie as far West as Smolensk. The four hundred miles that today separate Moscow from NATO represent a psychological distance. The country that Moscow rules and represents is its own thing – interactive with but not to be reduced to Europe or China. The nineteenth-century anguish over the question of whether Russia is European or Asian has now disappeared, and with it the fetishisation of Moscow as the guarantor of Russianness; globalisation has undermined the very sense of the question. That loss of urgency gives the Russians a breathing space, and Moscow – still physically heavy with Soviet and tsarist symbols – is now free, for the first time in its history, to be not a symbol, but to finds its way as the complex heart and head of a complex country.