It was 2001 and I was as footloose as I have ever been. Footlooser than I ever want to be again.

I threw myself up in the air, and was blown to New York.

For half a year I did a literary internship at New Dramatists (an organisation that supports American playwrights) in Hell’s Kitchen. I also did tele-sales for a linen company on Madison Avenue, lived on the floor of kind friends of a friend in Forest Hills, spent a large amount of time with a Sicilian waiter, learned Spanish from a Colombian and Russian from a Dane in Brighton Beach, joined an anti-death penalty group, and grew round on bagels and what the Americans term ‘bread’.

New York being closer to the Caribbean than England, I decided to visit the country that had respectively raised, and launched, two of my literary heroes – V.S. Naipaul and Derek Walcott. So I made a lengthy farewell to Alessandro and got on a BWIA plane to Port of Spain.

It turned out that one did not visit Trinidad alone. Not in 2001, and not as a woman. It also turned out that outside of carnival time (and I was visiting during its flat, exhausted aftermath), Port of Spain was not a tourist destination. As an unaccompanied, visibly unmonied, white, female tourist in the rainy season, I therefore posed a riddle. I might have been a sex tourist, but looked too poor and young for it, and was in any case on the wrong island; that would have been Tobago. I was not safe. One late afternoon in a shop, its female keeper advised me to urgently get back to wherever I was staying. Night falls like a knife in that latitude, and one doesn’t want to be on the streets after it has. For the first time in my life, I was named by my colour. ‘Eh, white woman!’ was flung at me on the streets with varying suggestions of surprise, amusement, mockery, and desire to start a conversation. People would nearly always tell me of a relative who lived in London. One evening, at a bar where I had been told that the black intelligentsia of Trinidad hung out, I met a Muslim geographer who worked at the Port of Spain Campus of the University of the West Indies. I told him that I had not yet been to any of the ‘rum shops’ mentioned so often in Naipaul’s novels. He invited me to find one with him. Breaking all the rules of safe travel, I entered his truck (which he had paid a little boy to guard on the street), and we cruised the suburbs, failing to find a single rum shop. Perhaps they didn’t exist any more, and this was just a prelude to our drinking rum on the terrace of his beautiful villa, overlooking the city. We talked about the human geography of Haiti. He delivered me back to my guesthouse. I live a charmed life; or perhaps I just had sound instincts.

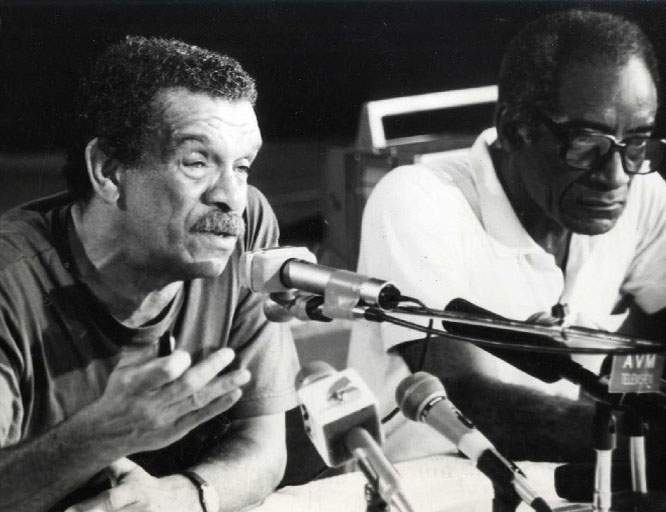

One day I marched into Trinidad Theatre Workshop, founded in 1959 by Derek Walcott and friends. It turned out that one of them, the actor Albert Laveau, still ran it. It was like at first sight. Albert greeted my interest in Walcott with pleasure, and became my avuncular companion. He fed me shark, and machete-split coconut, and told me about calypsonians, and one day said: ‘Derek is coming here tomorrow. Do you want to meet him?’

Derek Walcott and Albert Laveau

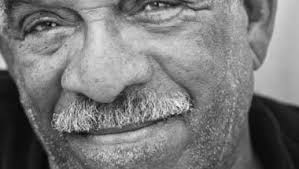

Albert Laveau around the time of founding Trinidad Theatre Workshop with Derek Walcott and others

The following day I had lunch under the equatorial sun with Albert, Derek, his family (he has one in Trinidad), and friends. I hardly spoke to him, except to ask to see him alone. He gave me a time at which to come to his hotel that evening.

I was slightly late. He was not impressed. I had not foreseen that he was the kind of person who would be unimpressed by someone being slightly late. I was overawed and determined not to be overawed. I put on my full Cambridge intellectual prickle; Derek recognised it and commented as much, being not without prickle himself. We discussed how difficult he finds it to write [his wonderful] prose, what literature is taught in Trinidadian schools, and how if I want to understand Trinidadian literature I must live in Trinidad for a while. He did not drink; he invited me to; I don’t remember whether I did or not, but it would have had little effect if I had. I had my full prickle on; alcohol didn’t stand a chance.

As a complete non sequitur to all that had preceeded, he suggested that we go for a drive. As we were about to leave Port of Spain, he said to me, ‘it’s still not too late to turn back, you know.’ We drove along the black coast, tense, alert, but no longer prickly, united in this adventure, both unsure of what we were doing. We pulled up at a raffish pool of light and sound in the countryside, a lone and busy nightclub. But before we had stopped, he had changed his mind. ‘Take us to town’, he told our driver. He dropped me off at my guesthouse.

I was, and am, full of regrets. I should have been older; I would not have prickled so. We would have talked more about his poetry, about history, about him.

I wrote as much to him, and some weeks later delivered this letter to his Manhattan apartment, along with an orchid. He had told me that he lived in the same corridor as Monica Lewinsky. Albert advised me that I would never get a reply, because his experience at Boston University had taught him to be wary of putting anything in writing to a woman. I never did.

Some years later I was teaching at Oxford University, and lecturing on Naipaul and Walcott. Sir Christopher Ricks (now a Visiting Professor, and my colleague, at New College of the Humanities) was Professor of Poetry, but was reaching the end of his tenure. I heard that Walcott was a frontrunner in the election of his replacement. But one of his rivals campaigned dirtily against him; he withdrew in disgust; she was elected, but was persuaded by the Head of the English Faculty to resign. Walcott did not re-enter the election.

I was sorry. I had no right to vote, but would have voted for him. Oxford needed him. He would have described the city well, in his poetry and his lecturer’s prose. And he would have been able to unEnglish the lecture theatre, precisely because he understood – but unlike Naipaul had never been seduced by – England. Our minds would have played like sea swifts in following him. As it was, I left him on a Port of Spain street. And am left with what he wrote for us.