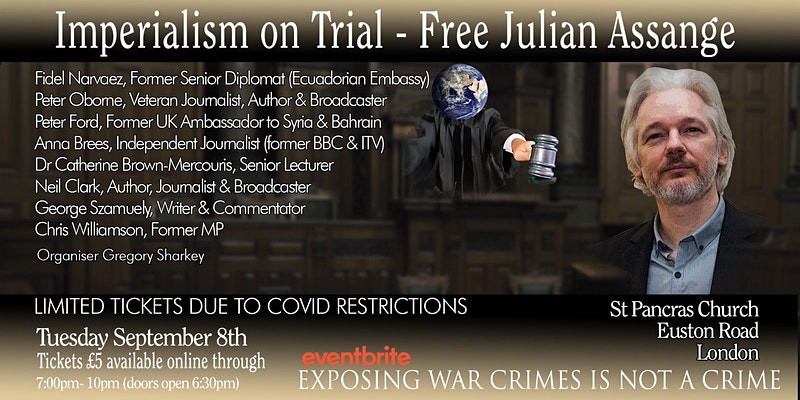

Tuesday 8th September 2020, 7.30-10.00 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK

Organiser:

Greg Sharkey

Speakers:

Catherine Brown (academic)

Neil Clark (journalist)

Peter Ford (former British Ambassador and campaigner)

Fidel Narvaez (former Ecuadorian diplomat, campaigner)

Peter Oborne (journalist)

George Szamuely (journalist)

Chris Williamson (campaigner)

Live-streamed by RT UK (my contribution starts at 18.25).

The event was held on the second day of the extradition trial of Julian Assange at the Old Bailey.

I gave a short talk comparing the phone hacking scandal with the Assange case. A version of this talk has been published on Consortium News.

For anyone unfamiliar with the former, here is a summary:

The UK phone hacking scandal started around 2005 and peaked around 2012. The journalistic malpractices and illegal practices on which it focused long pre-date 2005, and continue today. It came to light through the testimony of victims, and the investigative journalism of publications such as The Guardian, that several publications owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News International (UK subsidiary of News Corp), and others including Daily Mirror andSunday Mirror, were engaged in practices including hacking individuals’ phones and bribing the police in order to obtain stories. Rupert Murdoch’s influence over UK politicians was also scrutinised. Victims of phone hacking included members of the royal family, politicians, murdered schoolgirl Milly Dowler, relatives of British soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan, and victims of the 7th July 2005 London bombings.

The public outcry at these revelations and resultant investigations resulted in high-profile resignations including those of Rupert Murdoch as director of News Corporation, his son James as its executive chairman, and the commissioner of London’s Metropolitan Police Force. There were multiple charges and seven convictions in criminal trials held between 2004 and 2014. News of the World, a News International outlet, closed down after 168 years of publication.

In 2011 Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron established a public inquiry into the culture and ethics of the UK press under Lord Justice Leveson. This inquiry resulted in the 2012 Leveson Report, which made several recommendations concerning regulation of the UK press by an independent regulator, which would give alleged press victims access to arbitration without financial risk. Conservative governments since 2012 have declined to implement Leveson’s recommendations. In 2011 the FBI and the Department of Justice launched probes into News Corporation practices in the US, but no decisive action has been taken.

TEXT OF TALK:

Before I begin I’d like to mention someone who can’t be with us, but who is currently suffering under a politically-motivated legal case against him, a great advocate for press freedom, and for holding power to account. Can we please express our support for Craig Murray?

If you believe the word itself, the media mediates. It isn’t anything in itself. It transmits something else.

In general journalists do not want to be the story. They want to inform, disinform, persuade, distract, entertain, but not be the focus of attention themselves. This applies to Julian Assange as much as it applies to the journalists who hacked the phone of Millie Dowler.

But sometimes the medium does become the message, and the journalist becomes the story written by other journalists, as in both these cases.

We have seen Rebekah Brooks and others, and Julian Assange, arrested, put on trial, subject to huge amounts of journalistic attention because their journalism, it was alleged, broke the law.

In both cases the question of their methods overshadowed their matter – their matter being for example that Millie Dowler’s parents left messages on Millie’s phone in March 2002, or that US soldiers killed over a dozen Baghdadi civilians in July 2007.

These things were revealed at the same time and involved some of the same people. For example journalist Nick Davies was leading the investigations of phone hacking at The Guardian whilst he was working with Assange to publish the Afghan war logs.

But there are differences. And in those differences I think we see clearly one of the ways in which our society has gone wrong. Though I am going to be concentrating on newspapers, which have increasingly struggled since that time in print form, they retain considerable influence in electronic form, setting the agenda for TV news and therefore for politics. Their domination by a few magnates who have influence of politicians parallels the situation in social media, where voices that hold power to account are increasingly squeezed out, albeit in less obvious ways.

So let’s compare them. I’m going to compare them on seven points, then I’m done.

First, the motivation and nature of the legal investigations

The phone hacking scandal happened as a result of exposure by other journalists from 2005 onwards. The phrase ‘phone hacking’ described only part, arguably the least part, of what was revealed: journalists bribing police for information, evidence- and consequence-free destruction of individuals’ reputations, media magnates’ control of politicians and therefore politics itself.

The UK press had provoked six major investigations in as many decades, of which none had prevented the need for the next one. It was public feeling, especially in response to the revelation in 2011 of the hacking of murdered schoolgirl Millie Dowler’s phone, that induced the Conservative government to set up the Leveson Inquiry.

There were several arrests and convictions. News of the World’s Glenn Mulcaire was jailed for 6 months; Clive Goodman was jailed for 4 months. Previous News of the World editor, later CEO of News International, Rebekah Brooks, was arrested several times and finally tried on charges relating to phone hacking, and perverting the course of justice, in 2014, but was cleared. The newspaper’s editor Andy Coulson, after resigning from that post, was made Downing Street’s director of communications.

Meanwhile Leveson’s report into press culture came out in 2012, but under the inquiry’s terms this concluded only the first part of Leveson’s duties. Leveson Part 2 was to involve criminal investigations of journalists and police, building on the findings of Part 1. But in March 2018 the Conservative government announced that it was cancelling this plan.

In other words, the government prevented a planned investigation of journalists’ illegal activities, and of police collusion with those activities, for which there was a strong prima facie case.

In the case of Assange, as we know well, the government incited the CPS, and criminal prosecutors in Sweden, to investigate crimes for which the prima facie case was always more than suspect, in ways which have kept him in detention for as long as possible, and which have involved shocking derogations from legal protocol and of the independence of the judiciary.

The second point of comparison is the motivation behind the media coverage of these stories

In the case of the tabloid malfeasance, it’s quite clear that many of the journalists covering it were motivated by the public interest. It should be added that their newspapers’ proprietors didn’t have the close relationship with the government that, say, Murdoch did, and therefore they had less to lose from revealing this relationship. And the story enabled them to assert their difference from the journalists they were denouncing.

In the case of Assange, of course, those same newspapers, such as The Guardian, couldn’t in good faith do that because they themselves had published materials given to them by Wikileaks. But one gets the sense that they have since been trying to restore whatever relationship they had with the government, or responding to government pressure, by their subsequent participation in Assange’s character assassination – in which some of the journalists involved may also have partly believed, on the feminist, anti-Trump and anti-Russian grounds that have misled so many about Assange.

But the contrast between The Guardian’s relative fearlessness about a government embarrassment involving primarily domestic affairs, and its compliance regarding one involving primarily foreign affairs, the secret services, and the US, is indicative of a new dynamic in government-media power relations.

The third comparison is the attitude of the government to the media scrutiny

The government has not enforced the recommendations of Leveson I, and IPSO, which replaced the discredited Press Complaints Commission in 2014 has continued in its ignoble and ineffective course. In 2019 the former Conservative member of the House of Lords, Lord Faulks, was, in complete contravention of the principles of press freedom, appointed its Chair. Most UK newspapers are signed up to IPSO, and the result is that most of the coverage of Leveson has been hostile, and the press malfeasance which continues has dropped out of the news, other newspapers having given up on the cause.

The result is that anyone complaining to IPSO or the newspapers direct about the character assassination of Julian Assange, including clear lies such as Assange’s alleged meeting with Paul Manafort in the Ecuadorian Embassy, has no accessible recourse. Leveson recommended that newspapers enter a low-cost arbitration scheme, allowing redress for victims of press smears without the cost and risk of libel proceedings. The failure to implement Leveson has left us without that recourse.

Fourth, the motivation of the charged journalists’ work

In the cases of News International, The Mirror and the rest, the rank and file journalists were compelled by fear for their jobs and/or ambition, and the editors and proprietors were motivated by money.

Hacking the phones of 7.7 victims didn’t further their political interests, but the power they had over politicians helped them in weakening the law’s pursuit of them for doing this.

In the case of Assange, the motivation was neither money nor any political motivation other than the public interest served by revealing crimes on the part of states and other organisations.

Fifth, the contents of the accused journalists’ revelations

One thing that did follow from the phone hacking scandal was that the material illegally obtained was removed from the internet, so it can’t now be found. But it was for the most part trivial, so that, even when the hacked individuals were celebrities, it would have been difficult to argue – in those trials which will now not take place – that the revelations were in the public interest (as opposed to what the public was interested in. People may be interested that Hugh Grant briefly visited A&E in March 2011 when he was feeling faint, as The Sun told us, but it is not in the public interest to know it. Feeling faint is not a crime, and no crimes were revealed by the hacking.)

Assange revealed the most serious crimes possible – to the point of justifying the hacking with which Assange is wrongly accused of collaborating – yet post-Clive Ponting (the civil servant who leaked a damning truth about the Falklands War), the public interest in national security cases is defined however the government sees fit.

Sixth, the response of the majority of the public to the two scandals

In the case of the tabloid behaviour, there was considerable, widespread anger for a year or so. Then the majority of the press regained the narrative – managed to conflate the freedom of the press to break the law without a reasonable justification with freedom of the press per se – and smeared the characters of some of the leaders of Hacked Off. The anger has now died down, though its causes remain.

In the case of Assange, he has been largely successfully monstered by the majority of the press.

As a result, the wrong journalist is mistrusted, and the wrong journalists walk free.

In the case of Assange, who was revealing information of major importance, the way that the narrative of his alleged wrongdoing has dwarfed the narrative of proven, major wrongdoing that he provided, is astonishing. In both cases similar dynamics seem to have been in play.

My day job is teaching literature, and I’m well aware that it’s a peculiarity of humans to crave narratives. Most of us are interested in the lives of real or fictional individuals in a way that we are not in systems or abstractions. The thousands of lives illegally destroyed in Iraq and Afghanistan, as Assange helped to reveal, seem to many to be abstractions, whereas Assange’s alleged criminality is a story that can be followed. The countless journalists who help to corrupt our national life, and the media-political complex are, again, abstractions.

Who leaked the Labour report into the handling of anti-Semitism claims, or the US-UK trade documents, has the appeal of a whodunnit; a history of Labour internal sabotage, or a future of increasing animal cruelty and falling food standards, doesn’t.

There is also in both cases a sense of passivity and fatality – that of course Rupert Murdoch has influence over British politicians, that of course American soldiers commit war crimes, and of course modern technology gives the NSA and GCHQ scrutiny over our lives beyond the wildest dreams of the Stasi – but people like Assange, and Manning, and Snowden, may or may not get away with revealing these latter crimes, therefore there is something to follow. And thus our interest is successfully deflected from the largest scale onto the individual scale. There’s a good side to this. The details of individual lives should be followed, and amongst other things that’s what we’re here today to do for Assange. But for those following the stories without a grasp of the real abstract principles involved, the hero can be cast as a villain, whose suffering – as is true of all fictional villains – doesn’t matter.

But it losing of a sense of the large scale doesn’t always happen. Think of the Pentagon Papers, or Watergate. The MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009 dwarfed interest in how the documents that proved it got into journalists’ hands. Recent animal activists’ exposés of conditions in British pig farms such as Hogwoods have attracted more public interest than the illegal modes used to obtain the footage (it’s worth mentioning here that Wikileaks has revealed plenty about new so-called ag-gag laws in the States, which criminalise revelations of illegal commercial animal cruelty, and against which there is a considerable backlash, as there was when The Guardian in January of this year published police documents classifying animal and environmentalist groups, plus Stop the War, along with far-right extremists and jihadists for counter-terrorist response).

Seventh, the response of a minority of the public to the two scandals:

There has always been a small group of people who’ve remained focused on the crimes revealed in the phone hacking scandal, or by Assange.

In the first case they campaign for the prosecution of journalists who commit actual crimes in anything but the public interest.

In the second, they – we – campaign against the prosecution of a journalist who so far from committing a crime has acted overwhelmingly in the public interest.

These positions support each other. Proper press regulation would distance the media from the state, protect proper journalism, and permit redress for character assassination, which is why the National Union of Journalists supports both causes. Unfortunately not all of the leadership of Hacked Off sees the connection between their cause and Assange’s. But I do.

To conclude, some journalists are obeisant to governments. Some, like Murdoch, dominate goverments. Some, like Assange, hold them to account. Governments naturally react accordingly, and sometimes lean on the judiciary to enforce their response. But the revelation of this fact by other journalists can cause them embarrassment, and may hinder them from carrying on. That is what the journalists here today do, for Assange, for the public interest, and for us all.

Thank you.