Saturday 11th April 2020, 5.30-8.00 pm by Zoom (during the period of coronavirus lockdown).

The event was live-streamed by Action4Assange, Labour Heartlands, Consortium News and others.

Speakers:

Kristinn Hrafnsson (Editor-in-chief of Wikileaks)

Stefania Maurizi (investigative journalist)

Catherine Brown (English literature academic)

Peter Oborne (journalist)

Chris Williamson (campaigner and former Labour MP)

Craig Murray (blogger, historian and former UK ambassador)

Andrew Feinstein (South African politician)

Organisers:

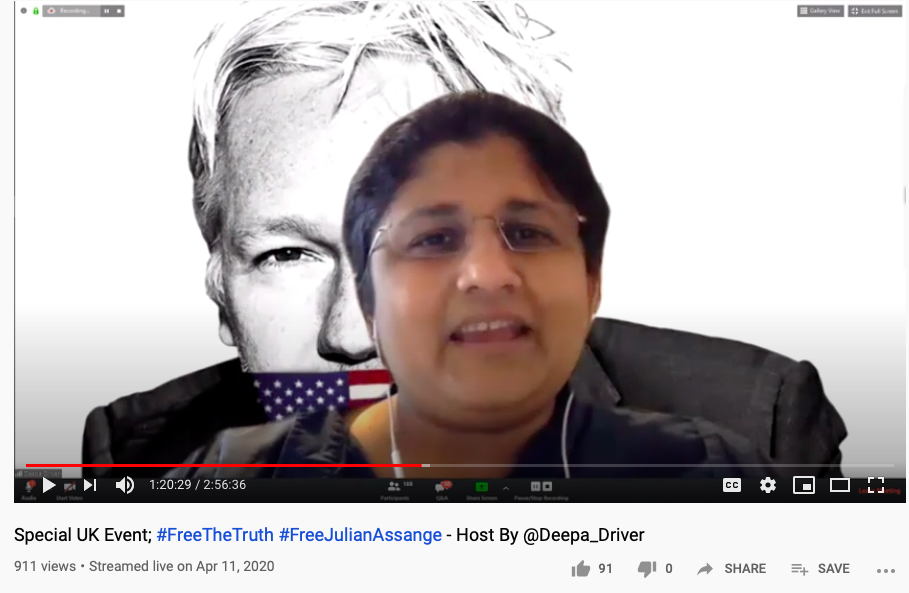

Deepa Driver and Iain Munro

The following account was written at the invitation of, and is published with the approval of, the event’s organiser, Deepa Driver (@deepa_driver).

The views expressed are the speakers’ own. I reproduce them in order to express support for the event, for Julian Assange, and for Wikileaks.

The following account is based on the notes that I took at the event. It is not a word-perfect transcription, but to the best of my belief it does not misrepresent any of the speakers’ views. I would welcome any corrections sent to catherine@catherinebrown.org.

For further materials concerning Julian Assange on this blog, please see my reports on:

Imperialism on Trial, 25th February 2020, 6.30-10.00 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK, with speakers Eva Bartlett (journalist), Mike Barson (music group Madness), Joti Brar (Workers Party GB), Neil Clark (journalist), George Galloway (campaigner and journalist), Joe Lauria (Consortium News), Peter Lavelle (RT), Alexander Mercouris (The Duran).

Free the Truth, 3rd February 2020, 5.50-8.30 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK, with speakers Craig Murray (former UK ambassador, now human rights activist), John Shipton (father of Julian Assange), Eva Joly (former French prosecutor, Green EU parliamentarian and member of the Development Committee), Lisa Longstaff (Women’s rights campaigner and spokesperson for Women Against Rape), and Nils Melzer (UN Special Rapporteur on Torture).

Free the Truth, Thursday 28th November, 2019, 5.50-8.30 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK, with speakers Lowkey (rapper), Lissa Johnson (clinical psychologist), Fidel Narvaez (former Ecuadorian consul), Lisa Longstaff (of Women Against Rape), Mark Curtis (historian and journalist), Nils Melzer (UN Special Rapporteur on Torture), Craig Murray (former UK ambassador, now human rights activist), and John Pilger (investigative journalist).

This write-up contains, at the bottom, general background information on the case.

Imperialism on Trial, 11th and 12th June 2019, St James’s Church, Clerkenwell, London, with speakers including Vivienne Westwood (fashion designer), Chris Hedges (Pulitzer Prizewinner), Clare Daly (Irish TD and MEP), Ogmundur Jonasson (former Icelandic Interior Minister), and myself (on the subject of character assassination).

Imperialism on Trial, 1st May 2019, Bloomsbury Baptist Church, London, with speakers including Kristin Hrafnsson (the Editor-in-Chief of Wikileaks), Annie Machon (former-MI5 officer), and Peter Ford (former UK ambassador to Syria).

Context for the date of the event

The previous Assange-related speaker meeting, Imperialism on Trial of 25th February 2020, took place on Shrove Tuesday, which was the second day of Assange’s extradition hearing at Belmarsh Magistrate’s Court. The present meeting took place exactly one year after he was removed from the Ecuadorian Embassy, twelve days after the refusal of his application for bail on health-related grounds, and hours before the voluntary publication of information about Assange’s family by his fiancée. Andrew Feinstein’s message that it is often darkest just before the dawn – as he testified from his experience of opposing apartheid in 1980s South Africa – fitted well with this event taking place on Easter Saturday.

KRISTINN HRAFNSSON

It is nearly a year since Assange was dragged out of the Ecuadorian Embassy. We saw the indictments we had been expecting for ten years, which materialised in shocking manner: eighteen counts, seventeen on the Espionage Act, which would amount to 175 years in prison. This was a grave attack on journalism – the worst I have seen in my lifetime. His persecution has to be resisted – but not just because of journalism; to keep our world sane and our democracy alive. We have this year seen a process which is extraordinary in the UK, which is perceived as having a robust and fair justice system.

On my experiences of the last twelve months I beg to differ. Assange’s is a test case in so many ways. Journalism is on trial. The current litigation pertains to the releases of 2010 and 2011 exposing war crimes and corruption on the part of the US; it is revenge, not justice – raw power being used in a deadly manner, a drone attack by legal means. It is like a slow motion version of the assassination of Soleimani in Iraq. We are seeing this more and more in American foreign policy. It’s scary, and it should be scary to everybody.

Who can we rely on? What about the left, what is left of it? Joe Biden is probably going to be the next Democratic candidate. In 2010 he called Assange a high-tech terrorist – so there is no hope there. In the UK Keir Starmer was the head of the CPS at the time that that office was actively engaging in a conspiracy to try to stall the moving forward of Sweden’s [rape-related] case. He was asked whether he would oppose Assange’s extradition to the US; he replied that he had faith in the UK justice system, which must take its course. I do not share that faith, on the ground of seeing so many things that have stunned me in the UK courts over the last twelve months.

A judge called Assange a narcissist after he said only his name and date of birth. He was sentenced to perhaps the harshest sentence for skipping bail in UK history. Another judge dismissed everything that was presented by way of mitigating elements – e.g. the UN finding that he was being arbitrarily detained, which the judge said had no bearing in this court room. Nils Melzer’s findings regarding torture were similarly dismissed; the UN apparently has no relevance to UK courts. Nor has the European Court of Human Rights, which had found – in a similar case – that keeping a prisoner in a glass cage was against the UN charter. Vanessa Baraitser has from the outset made it clear that she will look for anything to support the rubber-stamping of the extradition of Assange. There is no chance to persuade her; she has dismissed strong arguments. She has several times brought pre-written rulings into court, even though on the third occasion she had received nothing in writing from the defence in advance. So Assange is a political prisoner enduring a show trial in a UK court. Baraitser has denied him to sit with his lawyers, and has denied him bail even though he is facing the dangers of COVID-19.

Prisons are petri dishes for viruses and pandemics, just as cruise ships are. We know of two deaths amongst prisoners so far. No prisoner is currently being tested unless he falls gravely ill, but if any prisoner coughs then s/he is placed in a separate part of the prison containing everyone – with or without the virus – who coughs.

Any one of the arguments presented against the extradition should suffice individually to stop it – for example the spying on the legally-privileged conversation that Julian had in the Ecuadorian Embassy. Wikileaks had made a release concerning the CIA. The new CIA director at the time was Mike Pompeo, and in his first speech he named Al Qaeda and Wikileaks as the organisation’s two principal enemies. At that point we knew what was coming. That pronouncement didn’t result in an outcry, which was shameful on the part of the media, which has since been complicit in many things. We only saw a slight change last year after the severity of the US indictments became apparent – not due to passion about Assange, but due to seeing how close to home all of this was getting.

A year ago we had to start campaigning to save his life. Let us all come together in fighting for his freedom. Every day counts now and he must be set free immediately.

[Invited to give final thoughts at the end of the event:]

COVID is a stress-test on our society. Assange is a stress-test on our democracies. His case is not just about the individual person that I call a friend, but our society as a whole. I know that these are dark times, but things can move quickly, as we heard [from Andrew Feinstein] about South Africa. Nobody foresaw the swift turnaround in South Africa, Communist East Europe, or Albert Dreyfus. We are on the right side of history. We know this is what is going to be a test case. We will not be ashamed when our grandchildren ask ‘where were you at that despicable moment in our history?’

DEEPA DRIVER

I was in court earlier this week, and saw the way in which British justice is being delivered. Assange has had a chronic lung condition since 2012, he has mental health issues related to depression, and his trial in May is scheduled to go ahead as planned even though his lawyers are having difficulties communicating with him, he can’t meet his lawyers in person due to the lockdown, the video link room in Belmarsh Prison is in a shared space which is therefore dangerous, things are taking 8-10 days to reach him in the post, and there are about 40,000 pages worth of documentation to be shared with him. He is not being afforded equality of arms.

STEFANIA MAURIZI

I want to clarify why I have to speak out about Julian Assange. If he gets extradited then other Wikileaks journalists may be the next. I have spent the last eleven years working on the secret documents released by Wikileaks, republishing them in my newspapers, La Repubblica and others. I have never had any trouble – nobody ever had troubled me, arrested me, or made me seek protection in an embassy. I cannot accept this double standard – that I could publish the same documents that Assange did but with no trouble. We journalists have not taken any of the heat despite republishing his releases. I have a professional conscience. I wonder how many dozens of journalists have had huge scoops thanks to him and now are silent. Chelsea Manning – one of the greatest journalistic sources of all time – has spent eight years in prison, and tried to commit suicide three times. How can we accept this?

None of my colleagues were interested in the facts of what was going on with Assange. Nobody had a clear idea about the Swedish allegations, or had tried to get hold of the documents. Sweden is an open jurisdiction when it comes to freedom of information, so I thought that I could use the Swedish documents relating to Assange in order to get documents from the UK.

It worked. Initially the Swedish authorities provided me with 226 pages, which contained some of the most important information that we have on the case – for example how the UK and CPS were calling the shots in the Swedish case. Perhaps some people in Sweden disagreed with the approach of the prosecutor on the case at the time. But after that they stopped any collaboration. Why? The UK might have complained. At the same time the UK were still denying me documents. I started suing them. Since then I never stopped this litigation. I am still fighting in a London tribunal trying to get these documents. I haven’t even been told how many pages there are in the Assange file. The Swedes said that they couldn’t tell me this because the records are electronic. The UK said that they couldn’t tell me this because the records are only in hard copy. The UK did however give me an estimate, which is that between 2010 and 2015 the UK exchanged between 7200 and 9600 pages of communications with the Swedish prosecution authorities. After five years of fighting this I have seven lawyers in four jurisdictions, including three in the UK and two in the US – but have only 779 pages. The UK destroyed some emails but the Swedish authorities still have them. What I have is just the tip of the iceberg. What are they hiding?

[In response to questions:]

The most important documents I have published in English and Italian. As for the full set – I am still litigating so I am still waiting. I am doing this in a personal capacity. None of the newspapers that I work for support this kind of work. Now I get a grant which is paying for the lawyers, most of whom are working for very little, and some of whom are working for nothing: they want to find the truth.

How did we learn that the CPS had destroyed documents? In 2015 I could obtain no documents from the UK. I asked ‘why are you refusing, given that Sweden has provided me with documents?’ We told the CPS we wanted the full set of documents. They said ‘we have provided them’. We said ‘you didn’t, because there are huge gaps at crucial times.’ At that point the CPS wrote to me and my lawyers and said ‘we have destroyed the documents’. We asked ‘why, what were they?’ They said they didn’t know. Since 2017 we have been trying to discover what kinds of documents they destroyed, who did it, and when. Last month we filed a new appeal asking for information about this. It is very weird that they destroyed documents concerning an ongoing and controversial criminal court case. We are still fighting before the tribunal about documents destroyed by the UK, and are still fighting for Sweden for a copy of the documents.

I’d like to zoom out now to a big issue, which has played a major part in Assange’s case, and is part of a wider pattern of human behaviour. It’s the perversion of good impulses to negative ends – or, as the proverb has it, the road to hell being paved with good intentions.

In Assange’s case I’m thinking of people of goodwill who condemn rape, who criticise patriarchal distortions of the police and the judiciary, who believe that publishers have a duty of care to those about whom they publish; that political asylum should not be abused to escape justice; that recipients of asylum should not abuse their hosts’ hospitality; that states have not just a right but a duty to keep certain things secret for their people’s safety and in order to reduce conflicts – and which of us is not one of those people?

Yet it’s likely that many of us here today also believe that Julian Assange should be released immediately, and that it’s a priority to campaign for that. For other people there is a contradiction between those positions.

And the difference between us lies I think in these three things:

First, we keep in mind that even were Julian Assange a Russian-backed US-hacking Trump-supporting life-endangering justice-evading excrement-smearing rapist – there have been perversions of the law in the handling of his case; he is being psychologically tortured; and he is being unnecessarily placed in physical danger by the state – all of which would still in that scenario be outrageous abuses.

Second, we are in possession of different – that is to say accurate and fuller – information, which indicate that Assange is none of the things I’ve just listed. For example on the Swedish rape allegations, the excellent UK campaign group Women Against Rape has long argued that these have been manipulated to political ends in a manner that has nothing to do with the protection of women.

But why have we taken the interest and care to look beyond the mainstream media, which is what we’ve had to do in order to access this information? I’d suggest that it has something to do with how we handle our idealism.

And this is where I zoom out. Human history makes clear time and time again that idealism can lead to bad things. Ends can be used to justify means; collateral damage can be justified by intended damage, and the goals that supposedly justify that. One type of good can be seen to trump others – as we saw in the French and Russian revolutions with their justified terrors and their virtuous torturers – whereas in fact different goods can exist in an apparent tension that we need to negotiate carefully, never forgetting the individual.

Never forgetting that although millions of rich people, white people, Christians and men, have for centuries oppressed millions of poor people, non-white people, Jewish people, and women – it is not necessarily the case that any given rich person, white person, Christian, or man is necessarily guilty of any related charge. The belief, which is still out there, that Assange is guilty of rape because rape was alleged of him therefore has kinship with the revolutionary terrors, because in both cases collective justice annihilates individual justice.

Ideals become particularly dangerous when they are manipulated by the morally mad – or, as perhaps more often nowadays, the cynical. I’d like to quote Vera Brittain, the English socialist anti-war campaigner who as a young woman had worked as a nurse during the First World War. Looking back on that period in 1933 she wrote:

‘Between 1914 and 1919 young men and women, disastrously pure in heart and unsuspicious of elderly self-interest and cynical exploitation, were continually re-dedicating themselves … to an end that they believed, and went on trying to believe, lofty and ideal. … To refuse to acknowledge this is to underrate the power of those white angels which fight so naïvely on the side of destruction.’

So – to take the most extreme examples: Hitler harnessed youthful ideals that favoured helping the poor, bringing communities together, loyalty, courage, making Germany great again. And Naziism managed to achieve the amount of evil it did because of the amount of idealism it harnessed. Other dictators, who have done far less damage, have been less successful at least in part because they failed to harness the will to do good, which is so much stronger than the will to do bad.

Senator McCarthy reached out to the patriotism, the belief in freedom, and the class consciousness of the American working class, and used it to back his reign of terror, which – as again today – discredited anyone with actual or alleged links to Russia.

Liberal interventionists have harnessed the deeply rooted impulse to protect people to serve the ends of imperialism and the military-industrial complex which destroy people.

But on other occasions, certain ideals are appealed to in order to prevent people from acting on other ideals which have a more urgent relevance to a situation.

Defenders of Israel’s oppression of the Palestinians harness people’s revulsion from anti-Semitism and the Holocaust to dampen revulsion at the present oppression and to destroy those who describe it – as my fellow panellist Chris Williamson knows to his cost.

Too often the accusers, by placing themselves on the side of virtue, seem to acquire a virtue of their own which raises them above criticism, and inspires fear.

In Assange’s case, the harnessers of idealism have been the press, which – themselves manipulated – have united to assassinate his character. These finely coordinated attacks lend by their coherence an appearance of truth to those attacks, and make people resort to such untrue truisms as ‘no smoke without fire’.

The press has used lies, omission and obfuscation to engage the positive but irrelevant ideals that oppose rape, the evasion of justice, the abuse of asylum, and disregard for American lives – in order to disengage the relevant ideals that condemn torture, extraterritorial overreach, and political interference in journalism and the law.

Unlike Women Against Rape not everyone is morally careful enough to remember that not everyone is guilty as claimed, that individual rights matter even when group interests are at stake, and that there is very often a great deal of smoke without fire.

Therefore those of us who support Assange have to remember that we are up against is not just a conspiracy of active malice, vengefulness and bad faith – or even laziness and lack of interest – but good will and good faith, adroitly abused.

And to deal with that we have to point that out (which is what I have tried to do) – as well as get the facts out there: as loudly and clearly as we can.

That is what my fellow panellists are doing today.

[In the question and answer session Lisa Longstaff of Women Against Rape shared the following links and reminded viewers that Assange has never been charged in relation to sexual allegations:

http://againstrape.net/letter-on-arrest-of-julian-assange

http://againstrape.net/we-are-women-against-rape-but-we-do-not-want-julian-assange-extradited/]

PETER OBORNE

I made a great discovery as I was reviewing Wisden’s Almanac which was published this week. Wisden has unveiled facts about Assange’s cricket career which were new to me. His paternal great-great grandfather had four sons, all of whom were great cricketers. There has been a rebellion in cricket circles in Ecuador on his behalf: the Quito cricket club has offered him honorary membership. Their offer has been sent to Belmarsh, but he hasn’t yet responded. I have a cricket blog every week, and I’m going to bring this news to my listeners next week.

I am a British journalist – not a particularly distinguished or wonderful thing to be – but we try to find out facts. The more we can embarrass powerful people the better. Assange’s achievements in this respect are outstanding. He is journalist not just of the year but of every year in living memory. I wrote an article for Journalism Review a few months ago reviewing what he has done. He brought us earth-shattering pieces of information. Any journalist worth his salt would be proud to bring it into the public domain. He has had more scoops of great importance than the rest of us put together.

I’m here to say that I’m ashamed of my colleagues. Last year, when I was speaking about Brexit on College Green, the news came through that he had come out of the Embassy. The two journalists standing alongside me immediately took hostile positions against him. Their perspective was ‘good riddance to bad rubbish’. I think that that’s a betrayal of journalism, which we have seen on other matters too: the coverage of the 2019 general election, and of the virus. Shortly before last Christmas The Mail on Sunday had a front page story about the leaked diplomatic cables sent by the UK ambassador in the US. The British ambassador was rude about Trump. When the Metropolitan Police muttered about investigating The Mail on Sunday Boris Johnson and Philip Hunt defended it. Yet the situation was the same as with Assange, who revealed information of far more importance to the world. I am horrified that there is not a campaign by all newspapers to expose the abuses of justice in his case. If he dies in Belmarsh then we will have his blood on our hands.

The final thing I’d like to say as a British citizen is that I believe in the values of Britain: decency, tolerance and free speech. We’re suspicious of the muscle of the state, we celebrate Thomas Paine, Richard Cobden, John Bright, Keir Hardy, A. J. P. Taylor, Malcolm Muggeridge – all awkward customers. That’s what Britain is about – bloody-mindedly battling on and standing up for the underdog. That’s what we’ve done whenever we’ve been at our finest. And that’s why I believe that what’s being done to Assange is a disgrace.

I will write about this for various newspapers. And I will try to stir up some of my colleagues to convince them.

CHRIS WILLIAMSON

I look forward to the day when Julian can join us in the terraces watching English v Australia Ashes test match – hopefully not too far in the future.

We need him now more than ever, precisely because our representative democracy is not fit for purpose. The mainstream political parties are two sides of the same coin. Who are the parliamentarians representing? The UK government is prepared to spend billions of pounds on the vanity project that is Trident. There are inadequate supplies to protect our health workers from the virus. The UK is one of world’s biggest arms exporters. Who is holding politicians to account? Not the mainstream media. Shamefully, journalists haven’t come to Assange’s aid. Keir Starmer is allegedly a member of the Trilateral Commission, which was established in the 1960s out of concern about an ‘excess of democracy’. Joe Biden provides no opposition to Trump. The EU is obsessed with neoliberalism. We therefore need people like Assange to shine a light on the failings of our democracies.

You can download a copy of the extradition treaty between the US and the UK. He can’t be extradited for a political offence, or if a request for extradition is politically motivated.

We have to do what we can to embarrass the powerful. We have the opportunity to lobby our MP. No MPs seem to be raising this in the House of Commons. Ask your own MP why not.

CRAIG MURRAY

So much of this case is about the demonstrable power of the state. The torture of Assange is to a large extent being done because it demonstrates the power of the state and is intended to make us afraid. For example, it is meant to terrify Kristinn [Hrafnsson]. It is intended to stop us ever again releasing evidence of war crimes. Look at the malign way in which judge Vanessa Baraitser is conducting the case. All of us here who have been in the court have been stunned by her relentless hostility.

The other thing that horrifies me is that it is not just the case that the mainstream media doesn’t stand up for a fellow journalist, and someone whose only crime is to release state secrets. They openly attack him and do so with glee and hatred. That is something I find very difficult to deal with. It comes down to the disappearance of the civil society that we thought we were living in. Look at the countless blue-ticked journalists on Twitter making nasty remarks about him which they know to be untrue, but they say it anyway because it’s important for members of an establishment to kick out at others – the other – in order to establish group identity. It is a sign that we are going in the same way as Nazi Germany. Obviously I’m not saying that we are there yet, but it is scary.

One thing that was clear to me is that Baraitser is being ventriloquised. It is not just that she has written out her judgments in advance, and that for three hours she barely pretends to listen to the defence arguments and then reads them out. I don’t actually believe that she is responsible for those judgments. I’m fairly confident – from close observation of a week in the court during which I saw that whenever there were questions being raised she would adjourn court and then come back and answer the questions – that she is being told the answers to the questions. That she is a cipher giving out judgments handed to her by the Home Office. Again and again she was making judgments against the defence even when the prosecution did not object to what the defence was asking for, such as Julian sitting with his lawyers. It is normal practice in UK courts for vulnerable prisoners to sit next to their lawyers. The US government had no objection. Nor did it object to the postponement to the next stage of the hearing in order to give Julian’s lawyers access to him, and to allow witnesses to be brought in after the virus lockdown ends. There are five or six of these judgments. She claimed that she didn’t have the power to change his treatment in prison, which included strip searching and his papers being removed. The prosecution itself said that she did have such power. She was condemned for this claim by the International Bar Association. I can’t believe that I’m seeing someone I regard as a friend being crushed by the state. It is obvious to any observer. It is being cheered on by the media. It is a sorry reflection of the kind of society we are becoming.

The US and British governments have argued that the 2003 Extradition Act does not have a bar on political extradition, meaning that the 2007 Treaty bar on this cannot be valid. But only the 2007 US-UK Extradition Treaty allows extradition to happen at all. I know from my time in the Foreign Office that, when the Act was signed, there would have been a process of ratification to ensure that it was fully enforceable in UK law. If Clause 4 could not have been enforced it would have been flagged up and either the Act would not have been ratified, or secondary legislation would have been created to deal with it. I believe that the UK government is lying and that its own legal advice at the time was that it could have been enforced. I have asked my followers to made Freedom of Information Act requests about this. The answer is that the Foreign Office does indeed hold information on its ability to apply Clause 4 in UK law, but it cannot release it because that would take more than 3.5 days of work and would therefore be too costly. Yet this is the key point that the case now revolves around. It would actually take you about 3.5 hours to search it all out electronically and to present it. They are simply not prepared to do it. What I am looking at now is to make a series of information requests, concerning 2003-7, with different people asking for different information month by month.

[In response to questions:]

We can’t do much to influence the legal process. Julian has a first class legal team. I know that sometimes people of goodwill wonder why the team don’t put in certain motions at certain times. I can’t tell you, but I do trust Gareth Peirce. I trusted her with my life when she looked after me when I had left the Foreign Office and became a whistleblower myself. I am confident that he has the best legal team he could have.

Misfeasance in public office is very hard to prosecute. The Foreign Office tried to frame me on many false charges. The firm legal advice I got was that misfeasance in public office is almost never prosecuted. It is almost a dead letter of the law.

ANDREW FEINSTEIN

Listening to the other panellists has reminded me of life under apartheid, when I would sit in a court of law thinking that this is all theatre. It really concerns me this is happening here today, but taking the context that Chris [Williamson] has outlined, we shouldn’t be surprised.

Let us reiterate what Assange is being persecuted for. For revealing the crimes of the US government and its allies. For speaking truth to power. And if we are not able to stop this corrupt and illegal process we would not just have failed an individual in Julian, but failed truth-telling and journalism.

What Julian has done is violated the sanctified code of the national security state. Everything that happens in the domain of national security is veiled in secrecy. We remind ourselves that every day US and UK weapons are being used to murder innocent civilians in Yemen. If citizens were shown the true images of the conflicts that we are engaged in, finance and provide weapons for, then we as citizens would not allow this to happen in our name. Based on my research over the past twenty years it is not just the murder and mayhem of war-making that is being hidden from sight here. The global trade in weapons accounts for 40% of corruption in world trade. Who benefits? Politicians, corporate executives, consultants and lawyers make fortunes out of the arms trade. It is this bribery and corruption that oils the wheels of our corrupted political processes.

One can feel daunted, depressed and powerless. It’s a feeling that many people in South Africa grew up with in the worst years of apartheid. Some of us think that as we got towards 1994 there was probably a loosening of what was effectively a racist oligarchy. In fact it was the years leading up to the end that were the worst to endure, as the state claimed that it was starting a process of reform, but in the townships it imposed even worse oppression than had been seen historically.

But the movement never lost hope. I was forced to leave in the mid-1980s as I was involved in the ANC and was due to be called up for military service. I left the country at short notice, and looked down on my home city of Cape Town thinking that I would never see it again. But four years later Nelson Mandela was released and the ANC unbanned, and four years after that he was the democratically-elected leader of South Africa. And it happened as a consequence of an extraordinary international anti-apartheid campaign, and the fact that most South Africans made their own country ungovernable for the authoritarian regime.

So it’s at times like this that we should remember these experiences of hope and triumph. If we allow the state to continue to do as it pleases it will make us less safe. Instead we should spread information about Assange as widely as we possibly can. The power of information is the greatest thing. We must retain the sense that we can contribute in tiny ways. The volume and nature of those small contributions can create a tipping point.