I am rereading Graham Greene’s 1966 novel The Comedians, which I first read as an earnest fifteen-year-old member of Amnesty International. Then, it worked along with Amnesty’s literature to drive a stake of horror deep into my mind. A proxy sense of living under the worst of dictatorships has remained with me ever since, and helps to motivate my current work on torture and fiction.

Greene’s evocation of President François Duvalier’s Haiti has just prompted me to watch Alan Whicker’s 1969 documentary on the same subject. ‘Papa Doc’ ruled Haiti as its dictator and tyrant from 1957 to 1971, when he was suceeded by his son Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ until 1986. Some white anti-racists, like the American couple in The Comedians, showed the regime some indulgence. It had displaced the mulatto elite that had governed the country since the slave revolt of 1791-1804, and presented itself as the leader of black power worldwide. The US government had its own reason to show indulgence: Haiti was a bastion against Communism in the Caribbean; Duvalier came to power in the same year as Castro.

The hour-long documentary, made for the 1958-94 series Whicker’s World, cuts between footage of Whicker’s interview with Papa Doc (a highly unusual concession on the latter’s part), and footage – voiced over by Whicker – of street-level Haiti: American tourists staring uncomprehendingly at dancers holding themselves over an open fire; a dead chicken flung around in a Voodoo ritual; guardsmen sauntering with open-necked shirts and slackly-carried rifles; peasants sorting coffee beans; children running. The oscillation between the people and their President, between outside and inside the President’s palace or car, suggests their connection. Every sorter of coffee beans is continuously aware of the man in the Palace.

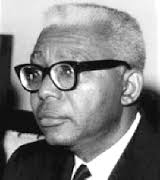

Papa Doc himself seems unextraordinary. The banality of at least some evil comes to mind (more sinister is Jolicoeur, the jocund journalist on whom Greene’s Petit Pierre is based). Duvalier is physically small, presents as elderly (he was only sixty-two), his glasses are thick, his lips are childlike, and his English is good. He is clever. But he does not take care to always make sense. Self-defence and self-promotion must have been amongst his priorities, but they were clearly not the highest. He shows no anxiety, and makes no effort of rhetoric. If his thoughts wished to unfold themselves in the occasional incomprehensible sentence, why shouldn’t he let them? He has already closed several embassies – including the British one – and expelled the Papal delegate one night without giving him enough time to collect his false teeth. His motivation for permitting this white man’s visit is opaque. That oddity presents the only context for understanding the eyes behind the glasses as the eyes that looked through specially-commissioned peepholes at the torture of Communists, critics, and wrong-place-wrong-timers. It is less of a leap to imagine this than to imagine those eyes helping him to treat patients and combat infectious diseases, as he did in the years in which he earned his affectionate soubriquet, before his days of office.

François Duvalier

And yet, watching him, one does not feel afraid. I have, of course, the distance of four and a half thousand miles, forty-eight years, and an ignorance of the Haitian Voodoo in which Duvalier presented himself as the deathless loa Baron Samedi, in which to feel safe. It helps, too, that Whicker shows no fear. He exudes Yorkshire Television safety. When the opening surtitles run: ‘THE BLACK SHEEP/ HAITI’S PRESIDENT FOR LIFE/ VOODOO DICTATOR/ AND HOST TO/ ALAN WHICKER’, the unintentional (I think) bathos of the last two lines enforces a sense of fine English comedy. Whicker’s fearlessness was less justified than mine, however. Haiti was already a pariah. One English journalist the less could do it little harm. Was Whicker not something of a comedian to venture into that country, as were Greene’s Comedians the Smiths? Greene had nightmares about Haiti for years after his fortnight’s visit in 1963.

Alan Whicker and François Duvalier in 1969

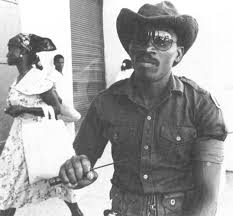

The lack of a sense of threat emanating from the documentary extends to the footage of the Tontons Macoute – personal bodyguard of Duvalier founded in 1959 to replace the downgraded army, which Duvalier did not trust. The Haitians nicknamed this force after the Creole bogeyman Tonton Macoute (‘Uncle Gunnysack’), who punishes bad children by catching them in his gunny sack (French macoute). In Whicker’s World, they look like relaxed armed policemen. In contrast to Greene’s description of them, they do not all wear sunglasses. If the very relaxation of their stance is sinister – indicating that they have nothing whatever to fear, and that everyone else, by contrast, is terrified of them – then this is not visible in the people.

A Tonton Macoute

And that, for me, was the most remarkable feature of the documentary. The people do not look frightened. They go about their various business. Whicker tells us in his voiceover: ‘You feel his menace in the pit of your stomach; you hear his presence in the silence of his subjects’. But we have to take his word for it.

Or Greene’s. In The Comedians a Haitian minister fallen from Duvalier’s grace commits suicide by cutting his throat rather than risk capture by the Tontons, who might have burned him to death. His body is returned to his wife – but during his funeral the Tontons smash the windows of his hearse and remove his coffin, determined to have him in death if not in life. The wife – if occurs to me – should have burned the body, privately. And scattered the ashes, privately. Only then could she have been sure that her husband was safe.

Fiction conveys political terror better than documentaries, one concludes. (Not all fiction of course. Live and Let Die, the 1973 film loosely based on Haiti – though for obvious reasons not filmed there – refracts certain elements of the regime through the thick prism of James Bond, and loses any sense of the people’s terror along the way).

In the same year as Whicker visited Haiti, the BBC made a documentary, ‘Garden of the Gods’, in which Gerald Durrell returned to the Corfu in which he had spent his 1930s childhood. He and Theodore Stephanides, his erstwhile mentor, together they wandered around the island which had now for two years existed under the brutal dictatorship of the Colonels. Of this there was not only no mention by the BBC (more compliant to anti-Communist imperative than was Yorkshire Television), but no sign in the people. Their fear was certainly less pervasive and intense than that of contemporary Haitians, but – such as it was – again it could not be caught on camera.

There is perhaps an exception, in the case of a dictatorship still more terrifying than Duvalier’s. In 1978, two years into his murderous governance, Pol Pot invited Yugoslav television to interview him and make a friendly documentary about his country. Such cheerful Cambodian music as is played over the footage makes still more sinister the facts that nobody smiles, their eyes are dead, or their eyes evade the camera; children are only seen working; everyone is well-behaved. At least the Cambodians were not also required, on pain of death, to appear cheerful. There seems something forced, and terrorised, about the cheering crowds at Stalin’s 1950 Mayday parade.

Yet are the Russians acting any more than the Haitians, who must dissemble their fear? Greene’s narrator makes it clear that to show fear to a Tonton is to bleed in the presence of a shark. No wonder that so much fear is illegible in documentaries – hostile or home-made – about dictatorships. And that Greene’s clever title broadens itself from the English to the French of his setting, making comedians comédiens – actors, not only those assured of a happy ending.