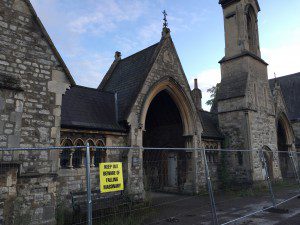

Paddington Old Cemetery, opened1855

My dogs – the most lifeful things, insofar as life consists of bounding and grinning and snuffling and sprinting – lead me daily through a vale of death.

Paddington Cemetery permits dogs off-lead on its twenty-five acres (unofficially and signposting to the contrary), and dogs are therefore the graves’ most frequent visitors.

My husband says that he would like nothing better than for his grave, in the fulness of time, to be daily bounded, snuffled and sprinted upon by grinning dogs. Not all grave visitors feel this way; some are vocally dog-phobic. But they are in a minority among the cemetery’s human visitors, it serving primarily the function of a park. The map at the entrance suggests as much, with its offer of two measured routes, a white path which is one mile, and a yellow path which is half a mile. ‘Enjoy Your Walk’.

Victorian cemeteries served this function in their own time too. They not only solved the public health crisis caused by the proliferation of urban dwellers – and diers – beyond what churches and their graveyards could cope with, but also supplemented the public parks which were springing up in the same suburban zone.

Kensal Green, London’s earliest of these, from 1832, quickly became a tourist attraction – as did Highgate, which followed in 1839. Darren Beach’s 2013 book London Cemeteries testifies to its subjects’ enduring popularity as recreation destinations. His tart but just comment on my neighbourhood is: ‘Kilburn is permanently on the verge of being London’s latest “up and coming” residential area, but until that comes to pass, the finest jewel in this built-up area of London is Paddington Old Cemetery’ (I would add to this the rival jewel of Kilburn High Road’s art-deco State Cinema).

In all of the cemeteries which followed the July 1832 Parliamentary Act ‘Establishing a General Cemetery for the Interment of the Dead in the Neighbourhood of the Metropolis’, the influence of foreign examples – notably that of Paris’s Cimetière Père Lachaise – is felt (though not as much as was planned for the first version of Kensal Green Cemetery, which was to have been built on Primrose Hill, and featured a pyramid with room for millions of bodies).

The development of cremation from the 1870s onwards, and its legalisation in 1894, had hardly an impact on the Victorian cemeteries. Even by 1914 only 0.2 percent of England’s dead were cremated. Since then it has risen to a majority, but that proportion has declined over the last twenty years, as burial has had a revival. Paddington’s JCB stands ever ready, and every other Saturday or so its metal maw bites a new grave for a new group of mourners.

One reason why I don’t like the word cemetery (from the Greek koimeterion, a room for sleeping, from koiman, to put to sleep) is that it looks too much like cremation (and of course, many cemeteries contain crematoria). Another is that it does not have the native beauty of graveyard, or of the even better German Friedhof (peaceyard). It sounds like, and is, a translation of nineteenth century French.

It also sounds municipal. And that is of course not wholly wrong. In the astonishing 1992 German television series Die Zweite Heimat, the protagonist Hermann visits a Friedhof and comments to a friend that graveyards resemble towns: the rich dwell in rich dwellings, the poor in poor, and like dwell close to like.

To some extent that is true of Paddington Cemetery. There is a barracks of small, uniform, hut-like white marble gravestones for the military fallen of 1919-23.

There is a communal dormitary of a marble slab bearing names of the Great War fallen. The 1930s left its mark on grave architecture as on domestic, municipal and industrial architecture, and the fashion seems to have been for wide horizontal family slabs – perhaps covering vaults – of which the Cemetery has a little street. The rich congregate together, as their Kilburn villas did and do, in a sequence of varying-sized obelisks, or large Celtic crosses. Kilburn was then somewhere for rich people to be proud of: one large grave records that ‘John Ring, MC of Kilburn, died October 21st 1896’.

But, just as English cities are not strictly segregated according to wealth, nor are the graves in this cemetery. There is much mixing of rank, of religion (the municipal cemeteries did not require membership of an Anglican church; the Jewish graves here are scattered among the rest) – and even more so of date. If this cemetery were a library, its cataloguing system would be inscrutable indeed. Each decade from the 1850s onwards has spread its graves over many parts of the grounds.

The recent taste seems to be for the straight line. New graves are dug closely head to toe for about fifty metres, then stop. Then death rushes forwards for another fifty metres, somewhere different. The new graves are hardly distinguishable, even by their flowers.

But a few of the older ones stand out. One, forever mourned by a woman of stone, is for a ‘Garibaldi Stephenson, who passed away March 28th 1932, aged 67 years’. One cannot help but compute that he was born in 1865, to Stephenson parents who, perhaps, had seen Garibaldi on one of his visits to England in 1854 or ‘64, and had perchance been eating Garibaldi biscuits since they were launched in 1861.

A Thomas William Bowlby, born 7th January 1818, died ‘in September 1860 while acting as war correspondent to The Times in China. Buried at Pekin.’

The dots – of his early death, its unspecified date, its location, and his occupation – are indeed to be joined. Bowlby was captured during the final, worst Opium War, and tortured to death in a Chinese prison in September, before being buried in Peking’s Russian cemetery. His widow, and mother of their five children, was buried at this place in Kilburn thirty-one years later.

The cemetery lies, like the great public secret that is death, at the heart of life. Four roads surround it: municipal, gentrified Salusbury Road; residential/commercial degentrified Willesden Lane; formerly working-class, now upper-middle-class Tennyson Road; and closest-Kilburn-comes-to-hipster Lonsdale mews Road. All of these face forwards onto life, and have a rear view of the peaceful dead.

Visible from the back upper stories of all their adjoining buildings is the great void at the cemetery’s heart – the 1855 chapel designed by Thomas Little.

For several years now it has been closed, and surrounded by fencing announcing the danger of falling masonry.

Money has been found to pave the entire cemetery to make it accessible to cars. Money is found to keep its toilets open to the public. But money does not exist, it seems, to keep the chapel open. It is not gently decaying, as did many an English rural church in the early twentieth century. It is being held, years-long, in a state of suspended animation, just as the red-star-shaped Communist fountain on Alexanderplatz in East Berlin was for years after the Wende. It could not be done away with; Communist feeling was too strong. It could not be renovated; Communism was too superceded. It could not be decided one way or another – and in any case there was no money – so the barricades went up and stayed up. I wonder how long this chapel will be held in suspension, an offence to Christians, and of no use to anyone else. If it ever becomes a café, let it be dog-friendly. Still better, let it become a dog-friendly chapel.