This article was published in the Newsletter of the D.H. Lawrence Society December 2014

‘There is’, remarked the non-Lawrencian who had come to join me at the thirteenth International D.H. Lawrence Conference in Gargnano, ‘a somewhat cultic quality about this.’

It wasn’t a criticism. Or I didn’t take it as such. But it made me conscious. Personal pronouns were used throughout the week, by the hundred and twenty Lawrencians gathered in the fishing village on Lake Garda where ‘he’ and ‘she’ spent winter 1912-13, without specification. Our raison d’être for gathering together in that place, the subject of our common knowledge, and cause of our mutual knowledge, needed no naming. ‘This is where his landlord lived.’ ‘This is where he saw the plays.’ ‘This is where he met the spinner.’ A reader of Twilight in Italy needs no more. I tried to imagine being at a different author’s conference. In Paris with Chaucerians all using ‘he’ in a similar way. I decided that I would understand by analogy. Having any author specialism makes you understand what it is to know and care about any one author well.

For us, in Gargnano this June, there was no blood-drowsed Southern sleep (and such Dionysiac ecstasy as was known must here pass without narration). The days were filled by lectures; Gargnano was filled by us and Lawrence; at night the heavens, as though noting our charged presence, stormed. My room in the Gardenia ‘al Lago’ was as good as in the lake itself, and on the first night I was woken by a tremendous flashing interchange. On and off went the sky, for an hour and a half. The lake was rained to froth, and Gargnano’s lovely face was flashed like a superstar’s.

Yet this crisis gave the heavens no peace. There were two lemon-yellow afternoons in which I swam, but no chance to turn nut-brown, like the neurasthenic New Yorker in ‘Sun’. It was not constantly hot enough, I was not naked enough, and there was ever the next panel to listen to. Thus were we kept on our mettle: timetabled England, with its uncertain weather, kept ever its hovering attendence.

Yet this was after all not pure Italy, which belongs further South. Lawrence only found Riva (still further to the North, in what was then Austria) Italian because he was coming from Germany. So, effectively, was I – a pale Northerner also dazzled by cypresses and limoncello. On closer inspection, the North was present there too, in a number of absences: of raised voices, drying washing, poverty, motorbikes, mafia, and the palpable male gaze. If Italy was twilit in 1912, then this part of it was now in blackest night, through convergence with North European norms. It is far prettier, more expensive, and more globalized than it was a century ago. It was after all, for a year and a half, the centre of the Salo Republic – and therefore at one end of an Italian-Teuton axis which Lawrence did not quite manage to predict. This aspect of its history is not denied, advertised or celebrated – but it was remarkable that the conference took place in the Palazzo Feltrinelli, Mussolini’s former operating base. Germans are still there today, still influencing its culture, but now with touristic respect.

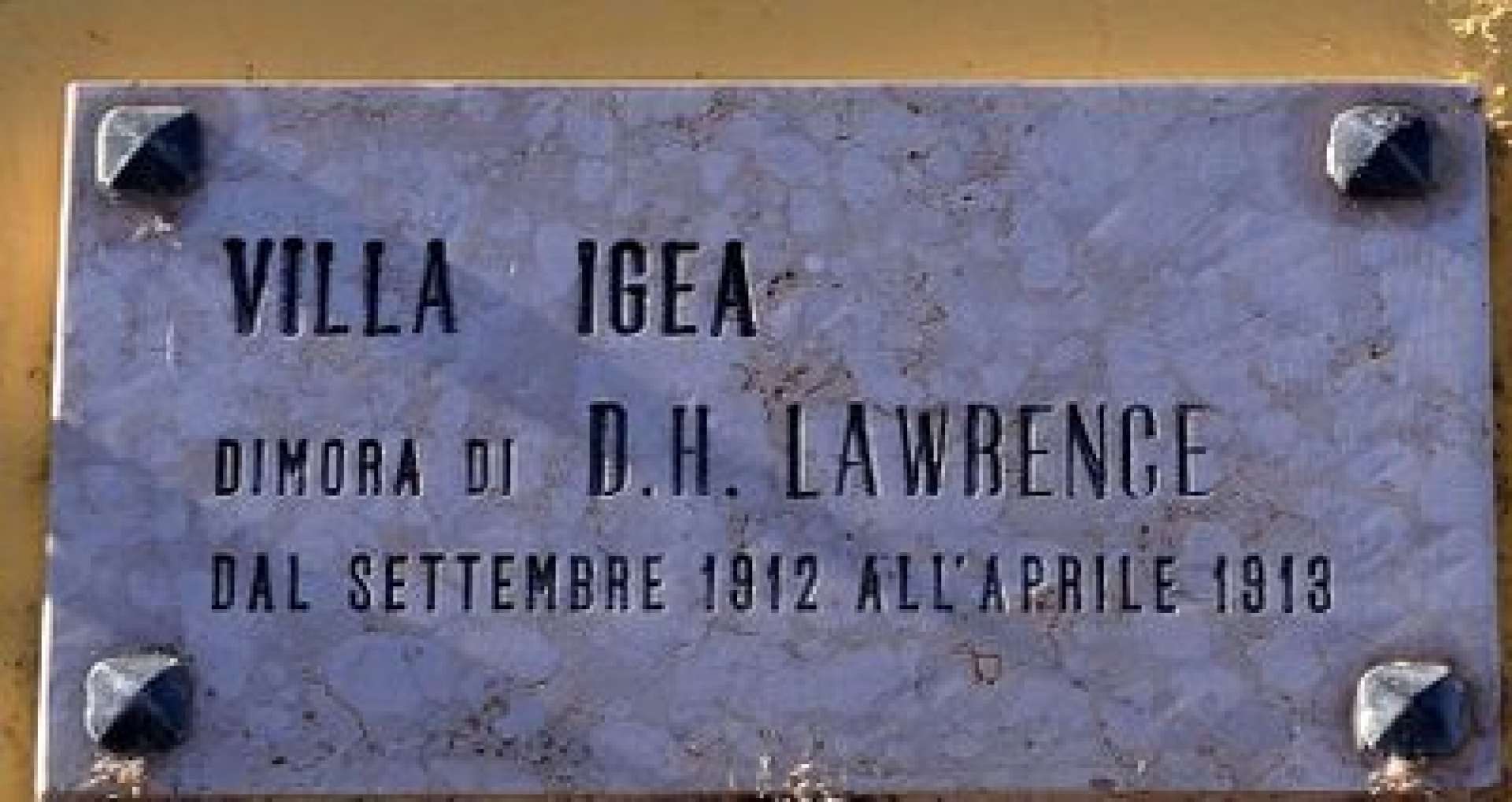

Frieda and Lorenzo found themselves an apartment in a villa one street back from the lake, labelled by a discreet marble plaque as:

VILLA IGEA

DIMORA DI D.H. LAWRENCE

DAL SETTEMBRE 1912 ALL’APRILE 1913

Flatteringly, to us, no explanation of Lawrence’s identity is given. The house is lemon yellow and egg white as a lemon-meringue pie. One can imagine the pleasure which they took in eating there the cheap, exotic Italian food. There we started a walking tour with John Worthen, which deliberately mimicked Lawrence’s difficulty in reaching the San Tommaso Church of the ‘eagle’. When we eventually reached it, not for the first time I felt forced to measure my distance from Lawrence’s creativity and/or perceptiveness. To him, the terrace outside the church ‘was another world, the world of the eagle, the world of fierce abstraction. It was all clear, overwhelming sunshine, a platform hung in the light […] suspended above the village, like the lowest step of heaven, of Jacob’s ladder. Behind, the land rises in a high sweep. But the terrace of San Tommaso is let down from heaven, and does not touch the earth.’ To me? It was a church terrace part way up a hill. And – crucially – the place where Lawrence had thought those things.

One evening we saw a performance, by local actors plus John Worthen, of The Fight for Barbara. Written by Lawrence during his stay in Gargnano, this play thought through the difficulties and possibilities (including disastrous ones) of his elopement with Frieda. Yet the play is of questionable comprehensibility to Italians. The husband threatens Barbara with his own suicide; an Italian husband of Lawrence’s period would have killed her or her lover, or abducted her, or at least threatened some such thing – certainly not talked about suicide. Barbara’s father reminds the lover that married women are out of bounds. An Italian man of Lawrence’s period would have seen a married woman as a particular prize, and certainly not have lectured another man to the contrary.

The main part of the conference was in the best tradition of academic conferences, with regard to location (which was lakeside), food (Italian), and intellectual content (of a kind which justified live presentation, and to which that presentation did justice). Sean Matthews chaired Keith Cushman and Michael Bell whilst wearing red trousers; this needed to be seen. Christopher Pollnitz read ‘The Ship of Death’ to a plenary session, uniting us in the experience despite all our hundred-and-twenty different relationships to death, perceived distances from it, and understandings of Lawrence’s relationship to it. If the conference was at all cultic, then this was a service.

We were free, and mutually encouraged, to be both academics and passionate strugglers into conscious being, and to share with each other why Lawrence mattered to us. Carol Siegel did the last particularly memorably, through her autobiography of her inspiration by and defence of Lawrence, in the contexts of her own early poverty and Second Wave feminism. Other recurrent topics were: Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Richard Owen introduced his new book about Rina Secker’s inspiration to the character of Connie), Lawrence in Italy in general and Gargnano in particular, translation, and editing. Linda Bree, general manager of the Cambridge University Press Lawrence project, represented the Press in celebrating the publication of the last major volumes of the series, the Poems I and II (although she pointed out that sales of the CUP volumes had gone down over the decades, as Lawrence became less popular). John Worthen criticised the decision to excise the results of Frieda’s collaboration with Lawrence as far as possible. Paul Eggert described editions as forms of slow criticism, taking their place in the long effort to understand great works. Editors are always down there in the fray, he said, and the work always seems just out of vision. Michael Bell was, as ever, simultaneously profound and precise in his description of the relationship between thought and being: ‘it is in their mutual nagging that philosophy and the novel find their difference.’

On the last day was an excursion to Riva, at the very tip of the phallus-shaped Garda. I found it even more Germanic than Gargnano. In the foothills of the Alps, the architecture has a Teutonic solidity and angularity of roof. The threatening Secession-style sanatorium is decaying into the hillside – as though the Italians, once they inherited South Tyrol from the Treaty of Versailles, did not know what to do with it, such institutions being culturally foreign. And so, one feature which Lawrence would have known as functional, is arrested in his own time. I found a second-hand bookshop and asked the assistant for ‘any D.H. Lawrence’. It turned out that some English people had come about a year ago and cleared him out of most of his Lawrence. These may have been the makers of the BBC documentary ‘Journey without Shame’, though I’m not sure. He still had something left, though: an Italian 1947 Lady Chatterley’s Lover – the edition which provoked the Italian Lady Chatterley trial over a decade before its remarkably similar English counterpart. I also found a 1912 German Baedeker guide to the Alps and North Italy – conceivably the edition with which Lawrence and Frieda navigated their way to Riva across the Alps – and came away well pleased.

We were going to go back to Gargnano by boat, having come by a road which post-dates Lawrence. As the eighty or so of us assembled at the docks, we looked just like tourists. I found this strange. We weren’t tourists. Not even literary tourists. We were…

We were people who had spent the previous week living in multiple dimensions. Our lives could no longer be read merely literally, for the plot, but had to be read also at historical and metaphorical levels. We had found the Villa Igea. We had thought of Lawrence finding the Villa Igea. And we had read his arrival, and our own arrival, through the prism of what he had written in the Villa Igea. I thought of my only other visit to Gargnano, the year before. Lawrence had slipped a year into the past, but a year’s worth of reading closer to me. ‘When at night the moon shines full on this pale façade, the theatre is far outdone in staginess’; ‘Now everything is theatrical’, he wrote. It was indeed like living on a set, where everything demanded literary criticism. Particularly when the documentary, in which I was involved, was shown in the theatre in which Lawrence saw Amletto, levels of meaning connected with an intensity which it was hard to absorb.

On the cruise back to Gargnano, significance gradually fell away, and for the first time in a week life began to resume its more usual consistency for me. This was simply a boat ride. We were about to arrive at an Italian village, where an English author had briefly lived. In the wake of significance came peace, and a slight disappointment.

And yet – at Verona airport there was a delay of a hundred minutes, so I had time to look around. There seemed to be noone else from the conference, which meant that everyone I saw had not been there. How strange, I thought, to have done anything else with the last week of one’s life than to attend the D.H. Lawrence conference in Gargnano. What on earth had they been doing? Why would one visit Venice, or Verona, rather than Gargnano? A fathomless mystery.

I spent the flight reading Twilight in Italy, intoxicated by it.

On my return, London felt enormous, and dangerous. Within this Northern city, I felt as never before, bad things happen, such as do not happen in Gargnano. Lawrence was rarely happy there, and wrote more consistently negatively about it than anywhere else. How strange that I should live there. Yet it had been agreed that the fourteenth International D.H. Lawrence Conference would take place there. Then it will generate, for each attender, its own series of resonances – when Lawrence is three years in the past and closer to us – as we, I hope, to each other.

I lay down Twilight in Italy, and slept.