Report of the Fifth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Marina Ragachevskaya

Minsk State Linguistic University,

Minsk, Belarus

Lawrence’s Reception in Belarus and Russia

Thursday 23rd January 2020

New College of the Humanities, 19 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3HH

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Liza Belozerova

Catherine Brown

Lara Feigel

Alex Korda

Pat Hopewell

Dudley Nichols

Jane Nichols

Trevor Norris

Dave Orwin

Iris Orwin

Anthony Pacitto

Patrick Phillips

Marina Ragachevskaya

Lara Taylor

Nahla Torbay

Aleksandar Vasilkov

Abstract

This talk will be part of a broader academic discussion of Lawrence’s reception around the world. Belarus cannot boast of a meaningful history of Lawrence’s translations, but it shares a critical perspective with Russian scholars, as Lawrence has been in the forefront of academic courses of literature for 30 years now.

I will tell an intriguing story about the first bold translations into Russian, the existence of at least four translated versions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, political control over reviews, as well as what it involved to actually “smuggle” Lawrence’s works into the classroom, and the striking similarity between Lawrence’s destiny and that of a Belarusian scholar who first introduced Lawrence to our universities. Lawrence spurred the cultural revolution in the post-Soviet countries in the 1990s and inspired even the Soviet sexologist to speculate on his works… These and other facts will make you surprised one more time just how a different culture opens up to the English author.

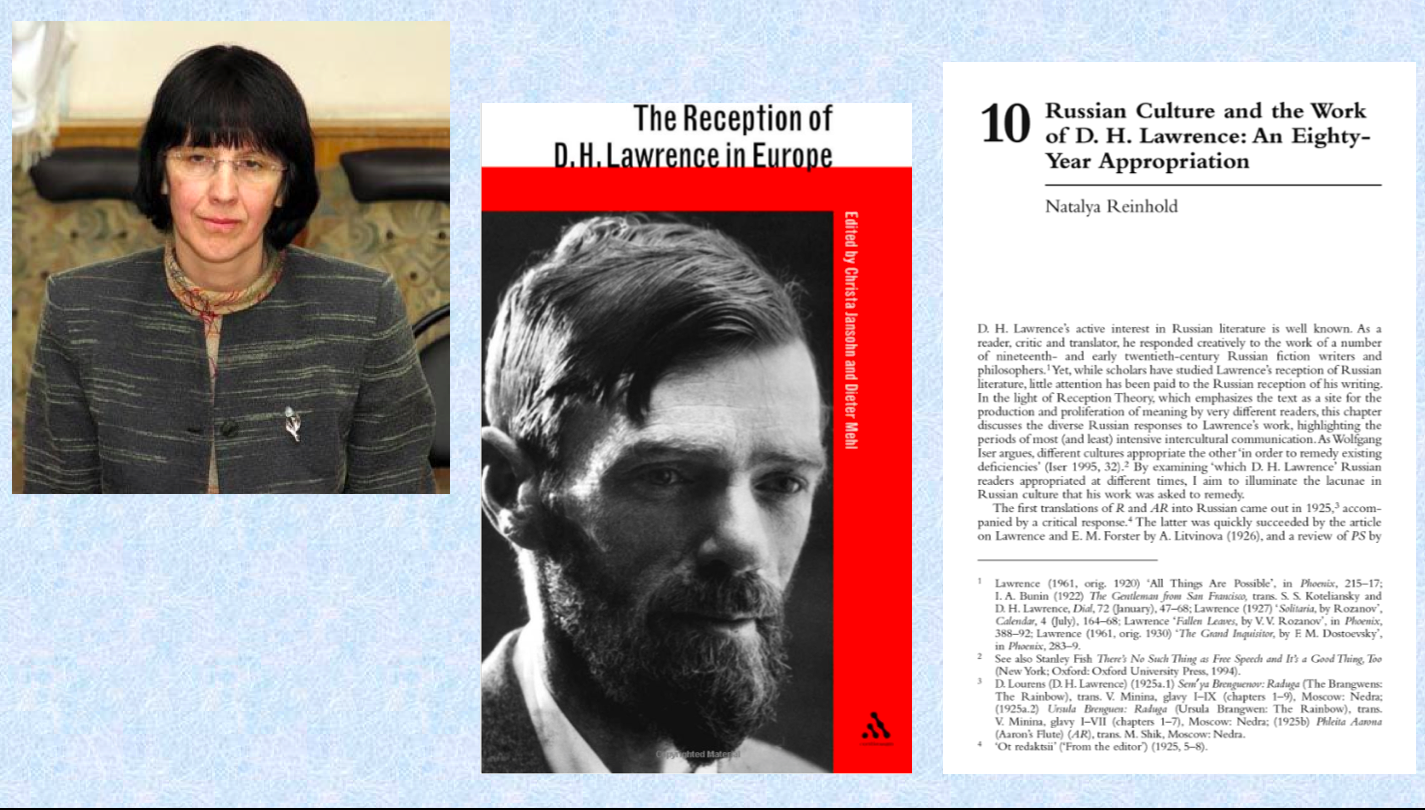

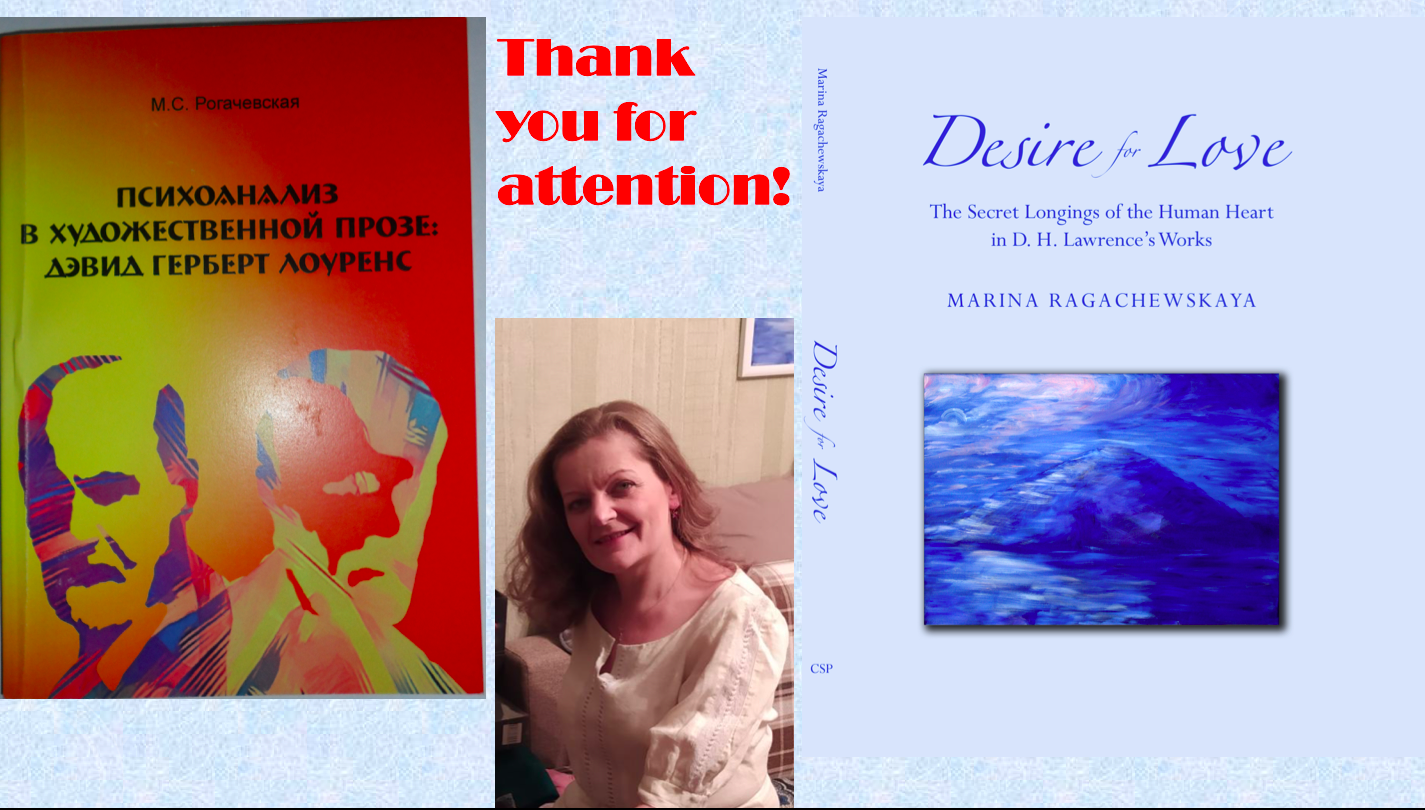

Marina Ragachewskaya

is a Professor at the World Literature department at Minsk State Linguistic University, Belarus. She has published widely on D.H. Lawrence, psychoanalytic literary studies and contemporary British writers (about 150 articles in English, Russian and Belarusian). Her recent books are Desire for Love: The Secret Longings of the Human Heart in D.H. Lawrence’s Works (CSP, 2012), Psychoanalysis in Fiction: David Herbert Lawrence – in Russian (Minsk, MSLU, 2013) and New Forms of Psychologism in the 20th-century British Novel – in Russian (Minsk, Novoye Znaniye, 2015). Dr Ragachewskaya completed her Post-PhD habilitation thesis in 2018, and was awarded the Habilitated Doctor degree. Her academic interests include fiction interpretation, psychoanalysis and literature, modernism and postmodernism, poetry interpretation, and translation. She has also given a lecture for the D.H. Lawrence Society of Eastwood on Lawrence and dance: “Tough Guys Don’t Dance? – What it Meant for Lawrence”.

Address

“Collapse, as often as not, is the result of persisting in an old attitude towards some important relationship, which, in the course of time, has changed its nature” – with these words Lawrence opened his article “Love was Once a Little Boy” (The essay “…Love Was Once a Little Boy” was written in America and published in Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine, 1925). It is very indicative for literature scholars, considering how the nature of life changes, in order to appropriate other ways of looking at, studying or teaching Lawrence today.

Why have I referred to this idea? Lawrence today and Lawrence about a century ago are very different versions in perceiving one and the same author and his work. Without actually dwelling of this rather broad issue, I think, today, Lawrence as a phenomenon has become a sort of simulacrum (A simulacrum (from Latin: simulacrum, which means “likeness, similarity”) is a representation or imitation of a person or thing. The word was first recorded in the English language in the late 16th century, used to describe a representation, such as a statue or a painting, especially of a god.

By the late 19th century, it had gathered a secondary association of inferiority: an image without the substance or qualities of the original. Literary critic Fredric Jameson offers photorealism as an example of artistic simulacrum, where a painting is sometimes created by copying a photograph that is itself a copy of the real. Other art forms that play with simulacra include trompe-l’œil, pop art, Italian neorealism, and French New Wave). In the same way, Lawrence’s portrait and titles of his works were so prolifically multiplied that sometimes the real resemblance, the inner significance and meaning were totally lost to be replaced by a visual image recognizable only because it used to mean something to someone. But that is the reality of today.

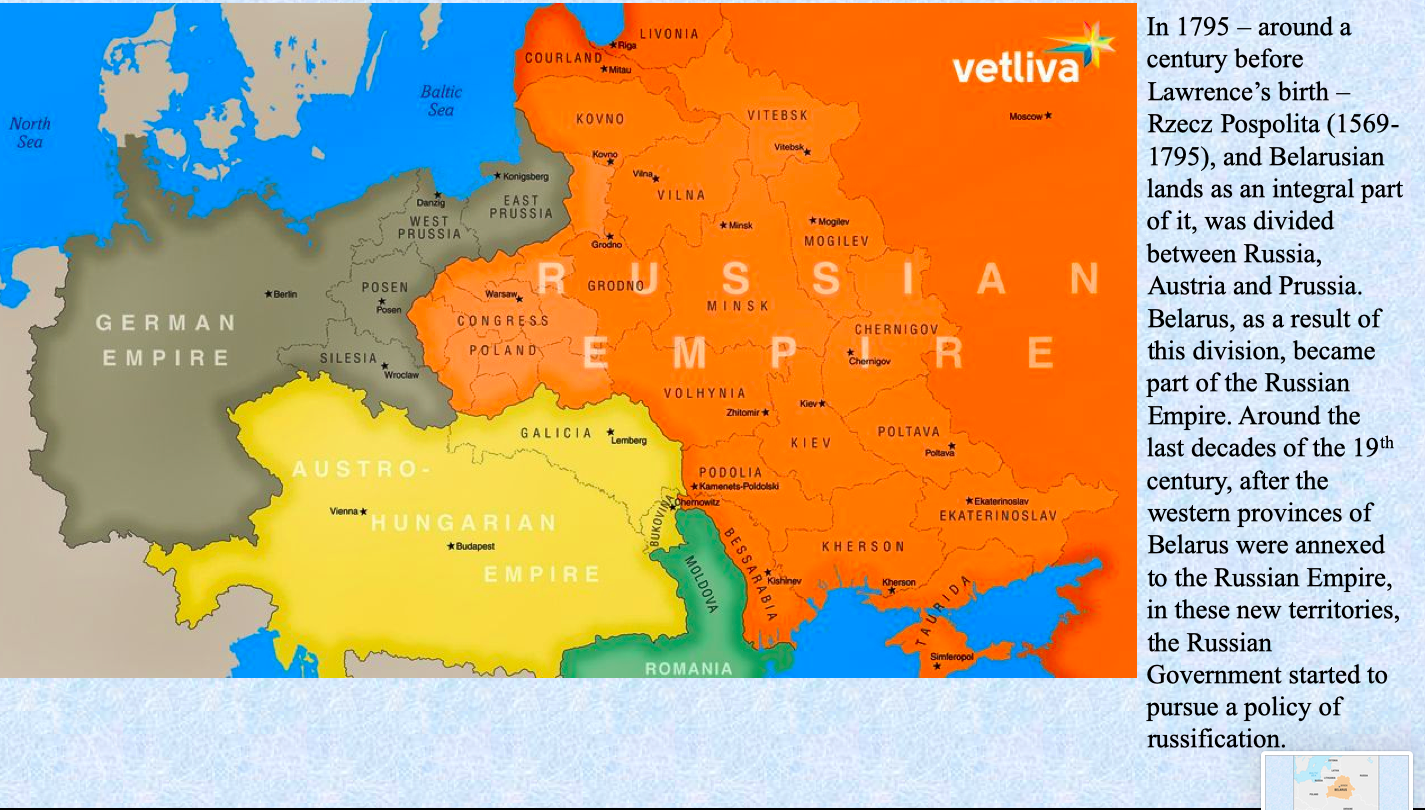

Speaking of Lawrence’s reception in Belarus, let us see, first, what Belarusian historical standing and cultural thought were like during Lawrence’s time span and immediately after his death.

In 1795 – around a century before Lawrence’s birth – Rzecz Pospolita (1569-1795), and Belarusian lands as an integral part of it, was divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia. Belarus, as a result of this division, became part of the Russian Empire. Around the last decades of the 19th century, after the western provinces of Belarus were annexed to the Russian Empire, in these new territories, the Russian Government started to pursue a policy of russification. Belarus had to partake of all imperial and military conflicts of the Russian government, including the Napoleonic invasion of Russia (1812), the 1917 Russian revolution, the Civil and the First World War. Throughout its existence as a Russian colony, Belarusians undertook a number of revolts. The revolt under Tadeusz Kostushko’s leadership (1794), the Polish Revolt (1830 – 1831) and the Great Rebellion, headed by Kastus Kalinouski (1863-1864) demonstrated that the people were not to be associated with the colonial policies of the Russian Tsar. In 1906, the Stolypin agrarian reform began, and, as a consequence, mass displacement of the peasant classes (from 1906 – 1916) with more than 33,000 that were moved from the Belarusian territory to Siberia.

During World War 1 – in 1915 – 1916 – the Belarusian territory was the scene of bloody battles between German and Russian forces. On the 3rd of March 1918 – signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, marked Belarus’ exit from World War One. The Belarusian territories were occupied by German forces until 1918.

The November 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia caused more national movements, and in March 1918 – the Belarusian People’s Republic declared independence. This lasted until the German withdrawal later that year. January 1st 1919 saw the creation of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. However, the Russo-Polish War (1919-1921) and the 1921 Riga Peace Treaty resulted in the partitioning of Belarus between the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic and Poland. Thus, in 1922 the Belarusian SSR became a part of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

In the years 1932-1933 horrible famine was brought about by the Soviet economic policy, and collective farming (Kolkhoz) was introduced. In 1936-1940 Belarusians, as well as all other Soviet nations, suffered the Great Purge. More than 86,000 Belarusians fell victim to political oppression, and over 28,000 were sentenced to death at Kuropaty camp near Minsk.

On 17 September 1939, two weeks after the outbreak of World War Two, the Red Army moved into West Belarus to forcibly annex these lands as well to the Soviet Union this time.

So the main national concerns were rather outside of the European cultural history of the time. However, this brief historical background may be self-explanatory of the fact of over-joyous, exalted and nearly religious welcome Lawrence enjoyed post-mortem in Belarus in the 1980s, and especially 1990s. Naturally enough, he was the emblem of freedom in all forms, which the citizens of Belarus had been deprived of for centuries.

When Lawrence’s short stories and poems were first published (1907), Belarus was deprived of its culture, the right to develop its own voice and, of course, it was drawn deep into the mess of the Russian imperial political concerns. When the writer became famous outside his own country, Belarus was still in part annexed by the Russian Empire. There was no way Belarussian intelligentsia could have any idea about the resonance Lawrence’s revolutionary outlook produced in and outside Europe.

An excursus into the Russian cultural thought of the time is more informative as to Lawrence’s reception in the Slavic countries. An excellent paper on the subject was published by the eminent Russian scholar Natalia Reinhold in the 2007 volume, ed. by Dieter Mehl, The Reception of D.H. Lawrence in Europe.

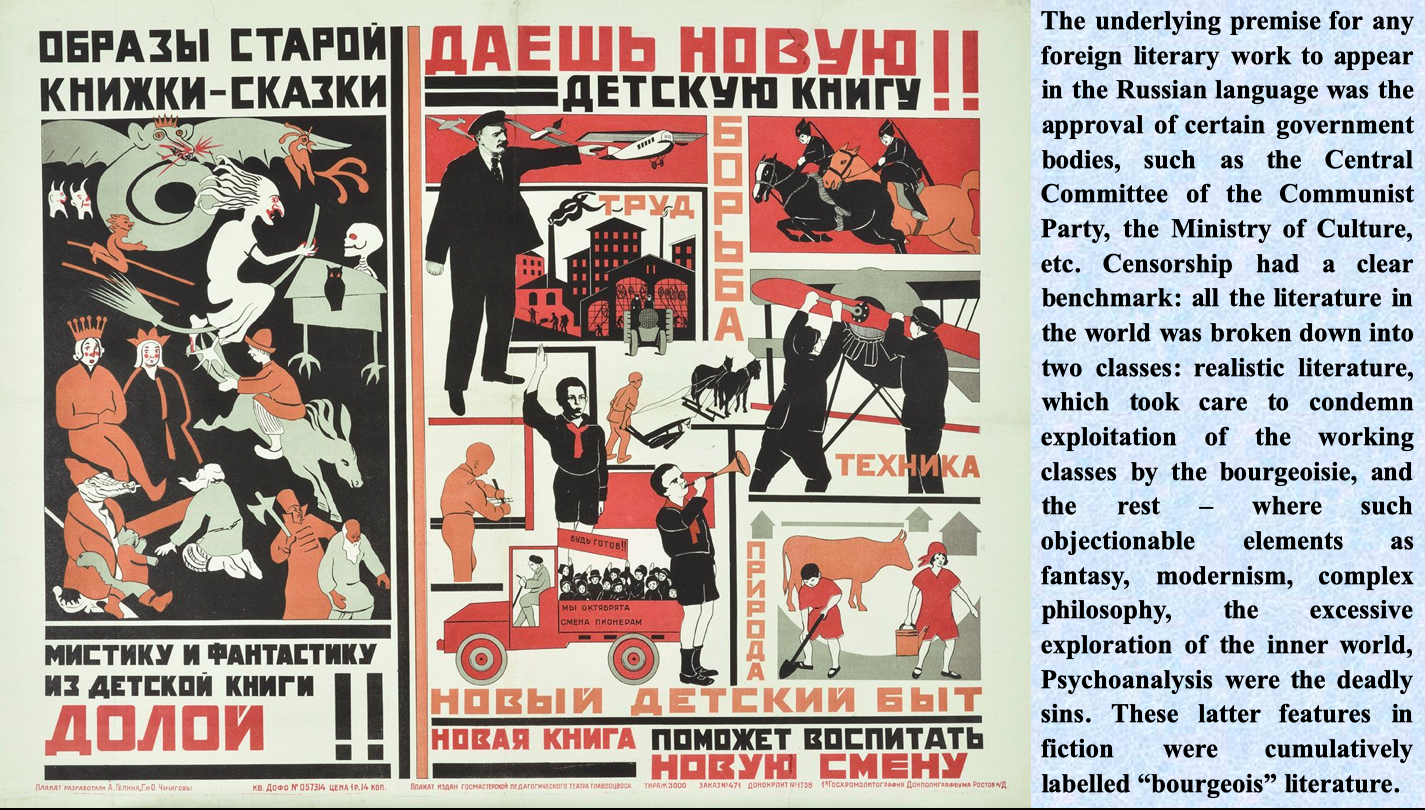

Thus, several novels and stories written by Lawrence were translated in Russia (the Soviet Union) in the 1920s. Perhaps, you should know that the underlying premise, vector and the driving vehicle for any foreign literary work to appear in the Russian language was the approval of certain government bodies, such as the Central Committee of the Communist Party, the Ministry of Culture, etc. Censorship had a clear benchmark: all the literature in the world was broken down into two classes: realistic literature, which took care to condemn exploitation of the working classes by the bourgeoisie, and the rest – where such objectionable elements as fantasy, modernism, complex philosophy, the excessive exploration of the inner world and – Psychoanalysis – were the deadly sins. These latter features in fiction were cumulatively labelled “bourgeois” literature.

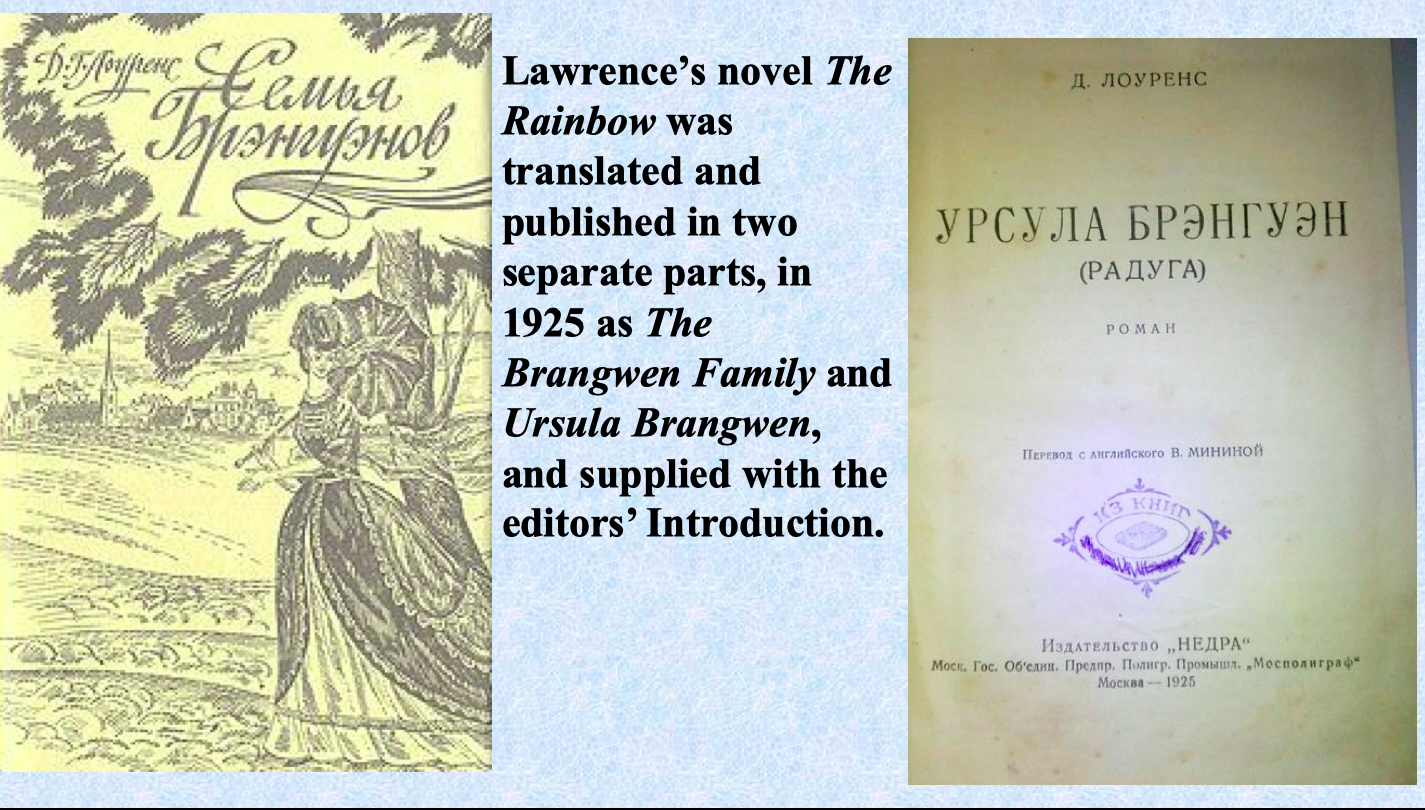

Lawrence’s novel The Rainbow was translated and published, curiously, in two separate parts, in 1925 as The Brangwen Family and Ursula Brangwen, and supplied with the editors’ Introduction. It is a historic document today, as it reflects in retrospect, what the Russian Soviet cultural thought held at the time in relation to Lawrence’s brilliant production.

I will quote some lines (with reference to the Russian scholar Maria Smirnova) and in my translation: “D.H. Lawrence is one of the most significant and original writers in contemporary Europe, whose works have been translated into all major European languages, enthusiastically welcomed by the young progressive criticism and causing indignation of the bourgeois public and clerics”. Further, The Rainbow is assessed as “an artistically strong novel” with “a psychological analysis of a contemporary female soul”; and the editors specifically remarked that for Russian readers, the novel was “undeniably interesting”: on the one hand, as a “work of great artistic value”, but, on the other, as “a characteristic phenomenon of the moribund bourgeois culture”.

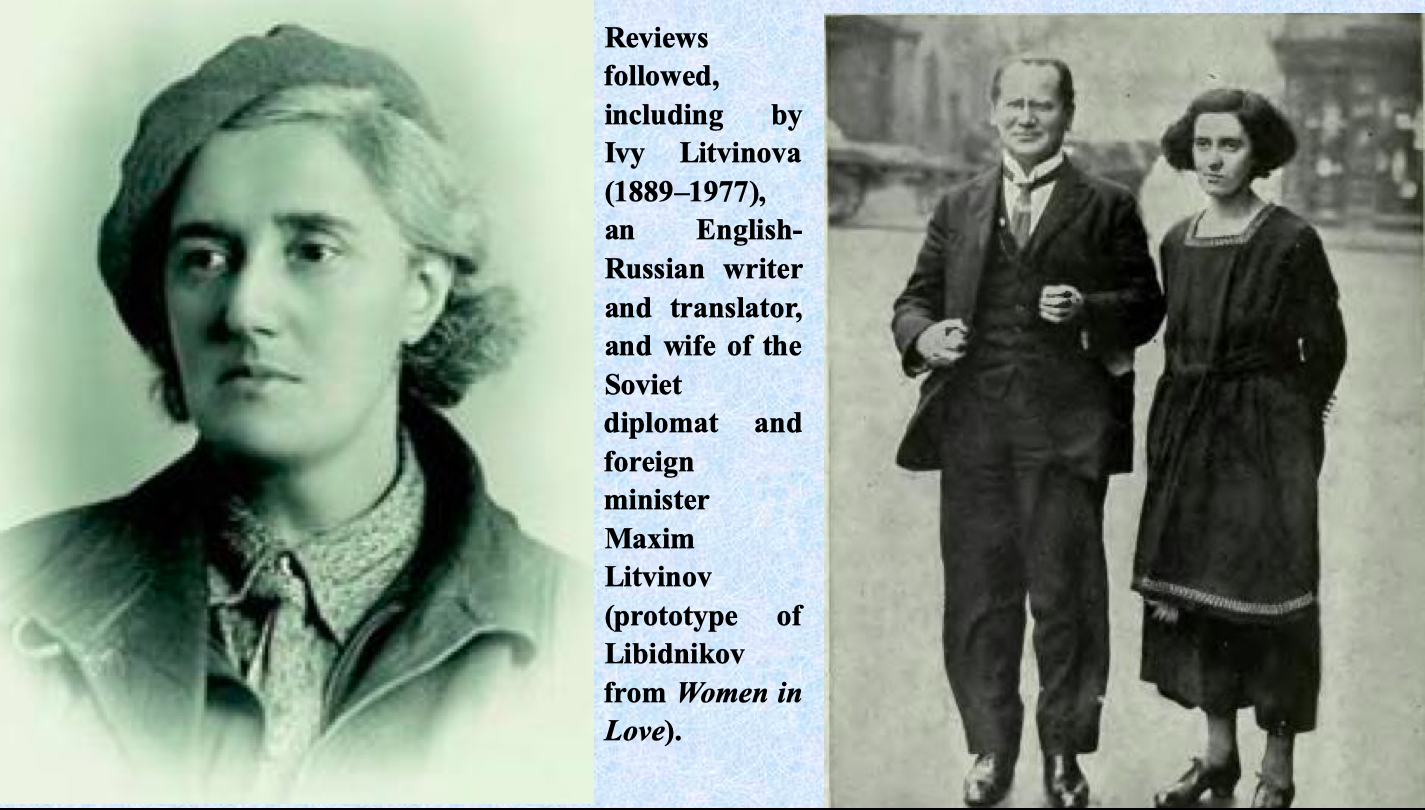

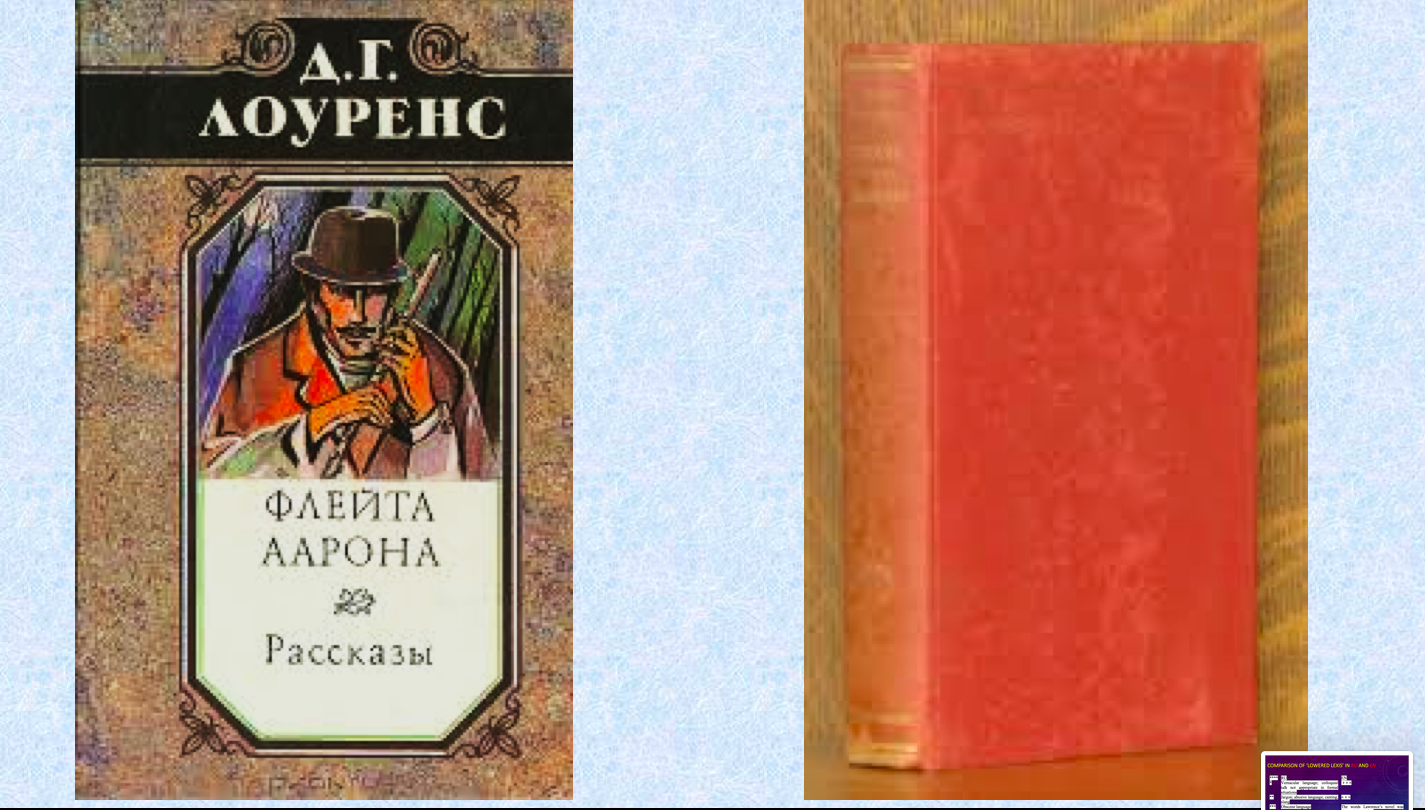

Aaron’s Rod in translation came out the same year. Reviews followed, including by Ivy Litvinova (1889–1977), an English-Russian writer and translator, and wife of the Soviet diplomat and foreign minister Maxim Litvinov (prototype of Libidnikov from Women in Love).

Lawrence’s works were first available to Russian emigrants in Europe. They made first, rather rough translations of random stories. However, they could not translate his work with due professionalism. Sons and Lovers appeared to fascinate many educated readers. The first translation was done by Korney Chukovsky, the Russian children’s author, poet, translator and editor. Unfortunately, it was unanimously judged as unsuccessful. N. Reinhold calls the 1920s period “the short-lived Lawrence wave”. After 1929, and until the late 1980s, Lawrence’s novels were neither translated nor published in the Soviet Union. The most likely sources of knowledge about D.H. Lawrence in Russia were the soviet writer M. Gorky and the émigré Koteliansky.

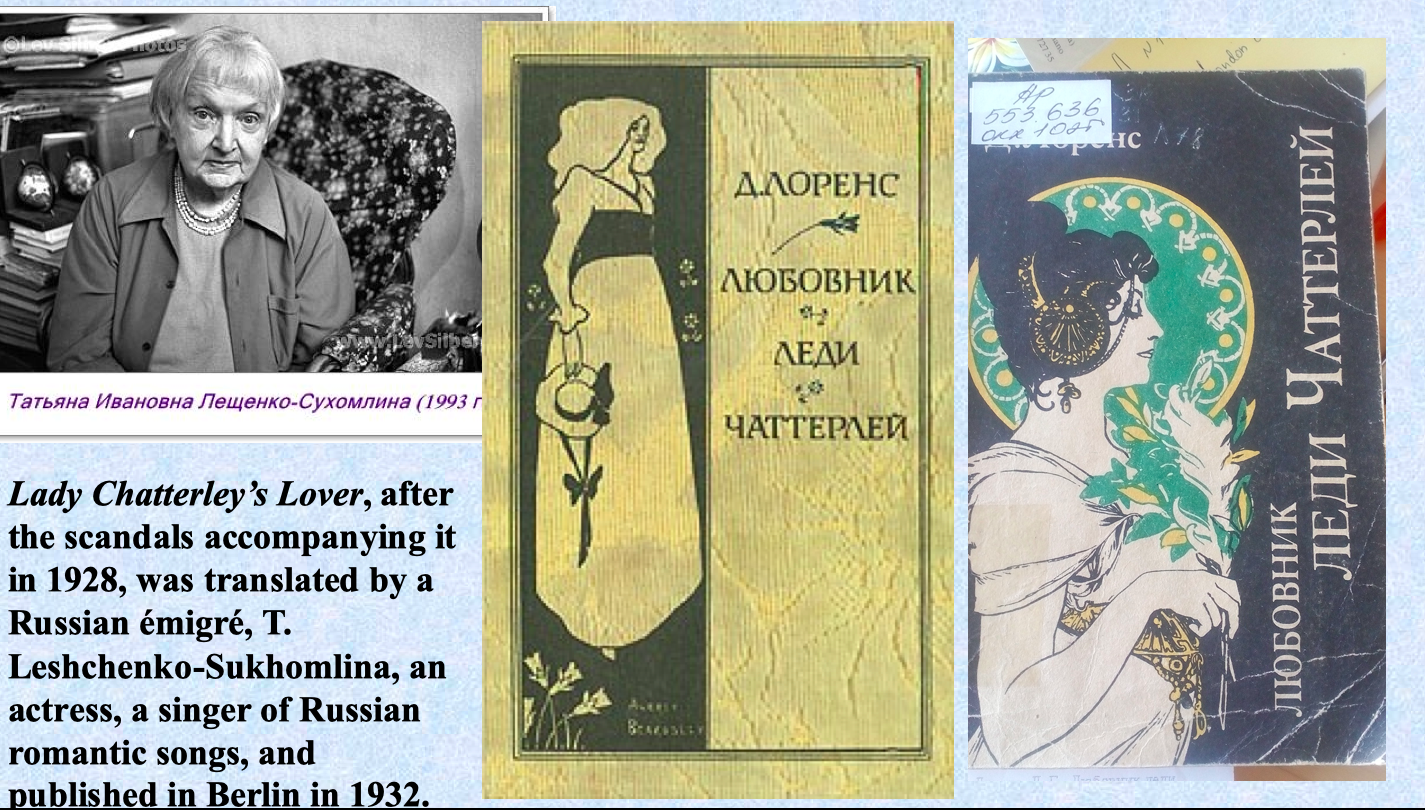

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, after the scandals accompanying it in 1928, was translated by a Russian émigré, T. Leshchenko-Sukhomlina, an actress, a singer of Russian romantic songs, and published in Berlin in 1932. From her memoirs, we can learn that she wrote to Aldous Huxley asking permission to translate the novel, as she found it chaste and honest. Unfortunately, she admits, Huxley’s letter of response was confiscated in 1947 by the NKVD officers during the ransack. Huxley’s letter, in Leshchenko’s words, welcomed this aspiration: Lawrence’s “will executor” gave her permission and expressed a hope that the translation would be brilliant. Indeed, for those times, the text was very well presented. The translator worked with the unabridged original, and any expurgations were her personal choice, not the censorship considerations. The novel thus was published in Russian translation in the Energiadruck not for mass sale and was sent to Povolotsky’s bookstall in Paris. In the same year, a book presentation was arranged in Paris by Russian emigrant literary community. Inspired by Lawrence’s and her own translator’s success, Leshchenko sent a copy of the book to Goslitizdat – the State Literary Publishers. The reply, surprisingly, admitted Lawrence’s great significance for Soviet people – because he was, according to the authors of that letter, “a former coal-miner (!)”, however, it also explained away the impossibility to publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover by the publisher’s overloaded publication stock for a number of years. Smuggling, however, was not to be disregarded. These copies of the translated novel reached Russia and were read in literary circles.

The response from the most progressive-thinking Russian writers and literary scholars (almost all of whom were émigré writers) was positive: among the merits of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, they even mentioned its influence on the struggle against bolshevism, and similarities in thinking between Lawrence and the Russian philosopher V. Rozanov.

However, there were severe blows from the authors like I. Bunin and M. Gorky himself: thus, for Lady Chatterley’s Lover Gorky labeled Lawrence “a priest from an English parish. A dull priest at that” (ref. to Reinhold and her translation of Gorky’s letter to K. Fedin).

The critics’ response and assessment of The Rainbow and Women in Love (to the English version, as there were no translations yet) in the 1920s was strictly socialist by nature: it was noted that Lawrence’s “half knowledge” of psychoanalysis “hovers” over The Rainbow, while Women in Love was proclaimed “infelicific” (ill-fated, unfortunate, disastrous).

One more translation deserves attention. In 1935, “The Prussian Officer” was published in the Soviet monthly journal Znamia (Banner). It served purely political and ideological purposes, as “part of the anti-German propaganda campaign” (Reinhold).

Four variants of Lady Chatterley’s Lover’s translation are in existence today, starting from the above mentioned 1932 pioneering edition to be followed by the 1989 translation by I. Bagrov and M. Litvinova, the 1991 text by I. Gul, and the 2000 version by V. Chukhno. While the 1989 version is universally recognized as the most adequate, it is evident, that readers are still not happy with what is available in Russian. And it is not only the “obscene” words that impede the quality of the Russian translation: it is Lawrence’s inimitable diction and style that makes translators’ stop dead at numerous passages and descriptions. For this reason, many other texts in Russian translation contain mere omissions. Evidently, the translators would enquire: why repeat the same things over and over again? – but we all know how recurrences are all significant in Lawrence’s works, and that their functions vary from emotional emphasis to almost musical and even corporeal impact on the reader’s consciousness and the unconscious.

Indeed, scholars in Russia and Belarus continue to be unhappy about some translations. For example, the understanding of certain realities Lawrence described was poor: thus, in The Man Who Died, M. Koreneva misunderstood the description of the cave where Lawrence’s character was first buried, which looked like “ deep cupboard” (or a small part of a room with a door behind which there is space for storing things, usually on shelves), and gave in the Russian translation the word meaning “a piece of furniture”. Another problem concerns the word “scullery”. Because of the actual absence of this reality in the old Russia, it is almost impossible to name the place – the translator’s comment is needed. Further, when “speaking broad” is concerned, the dialect is untranslatable, either. You cannot make Mellors speak like a Russian muzhik (a peasant with a distinguished local sub-dialect, or lingo).

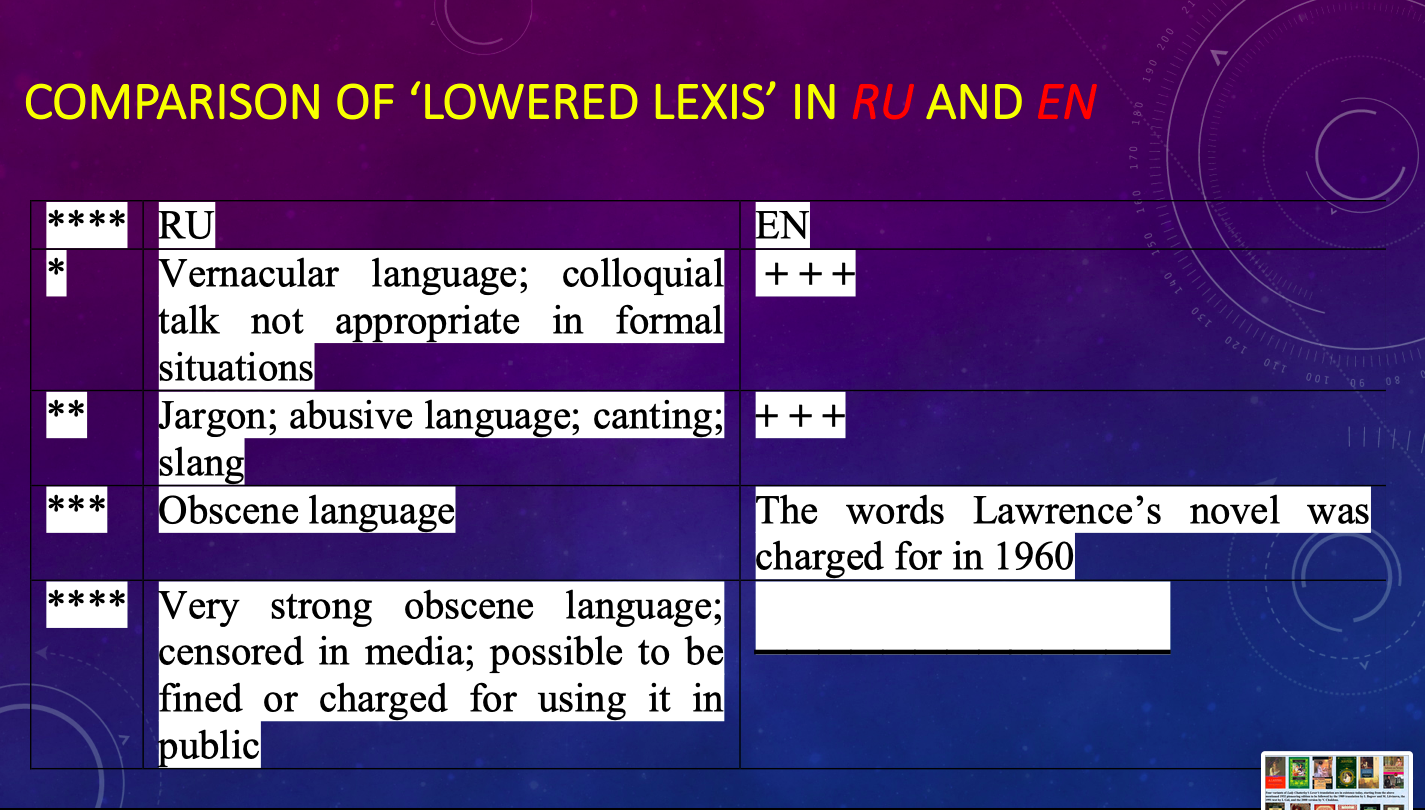

The problem of “obscene” words is another issue for translation. Several levels of “lowered lexis” in the two languages demonstrates this “catch”.

There are numerous other misconceptions, translation errors and cuts. It is interesting that besides the notorious “obscene” descriptions, including those in the hugely abridged version of The Rainbow, Lawrence’s allusions to the Bible were omitted, as well as certain recognizable biblical vocabulary units. One of the most evocative cases, is the replacement of the word “rod” in the title of “Aaron’s Rod” by the word “flute” in translation. This leads to a very important conclusion about the spheres that are most likely to be repressed by a totalitarian regime: the sexual, the political and the religious. And Lawrence was a concoction of all of them simultaneously. So, while trying to annihilate and curtail one of these, they inevitably crippled the rest of the book creating a skimpy and perverse imagery, message and philosophy.

The 1960s as the time of all revolutions, including the revolution in bringing Lawrence back to life had its toll on the appearance of, if not new translations of his books (only sporadic short stories), but at least of the exported English books, as well as these books becoming available in the central Soviet libraries – the main one was in Moscow. It is also worth mentioning that the KGB would thoroughly study the contents of those books which were delivered from abroad. Any objectionable content that “threatened the security of the state” made the book available only for authorized use by special government-approved researchers. With all that strictness, it was utterly surprising for me in late 1990s to discover among such volumes quite a few that bypassed censorship to which testified the fact of uncut pages in the editions of the 1930-50s.

Among those were Lawrence’s “Fantasia of the Unconscious” and “Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious” as well as Herbert Read’s essay collection “To Hell with Culture” which notoriously blamed and cursed bolshevism and the Soviet system. Perhaps there were not enough linguistically educated security people in late 50s and 60s to properly deal with the inflow of books from abroad.

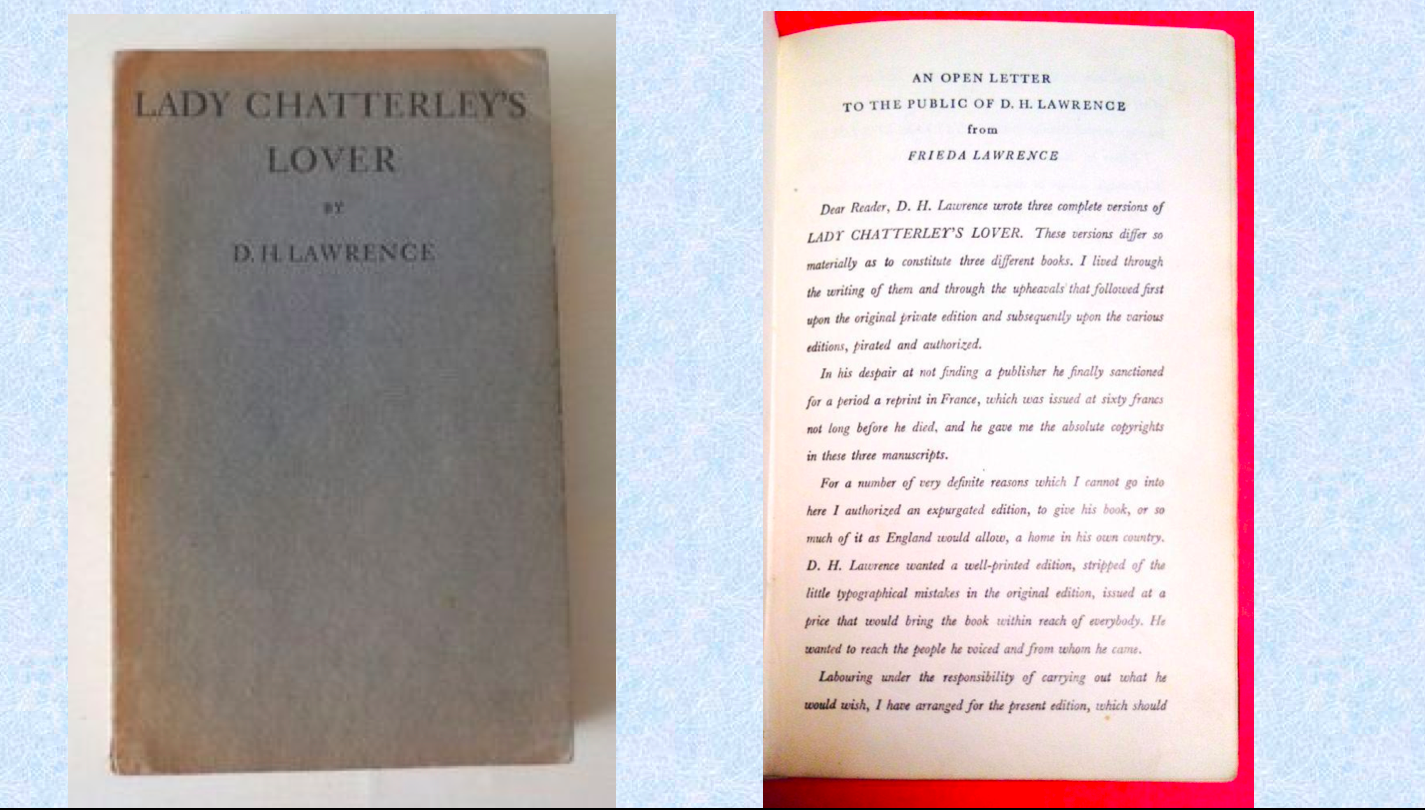

Among them, was an impressive collection brought to Belarus by L. Cortes. A rare copy of the 1933 impression of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, published in Hamburg is in possession of one of our retired professors, Renata Fastovets. This is a famous edition: it opens with Frieda’s introduction entitled “An Open Letter to the Public of D.H. Lawrence from Frieda Lawrence”.

Lawrence’s name and references to his works appear in the first textbooks on the history of foreign literature in Soviet universities. He was not part of the curricula of course, but in the 1948 and 1954 textbooks on the History of English Literature (by A. Anikst) half a page was dedicated to Lawrence, and certainly, with a label of a “reactionary” writer.

One Belarussian Soviet scholar’s personal biography mirrors those exiles and unacceptance which run through Lawrence’s life. Liudmila Pavlovna Cortes wrote her first book about English literature in 1974. It was an act of courage to mention Lawrence in the context of the bourgeois modernist literature:

“The name of D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930) is worthy of attention. He was an admirer of Freud, too. At the same time, however, he stood very near to the realistic principles in Art. The son of a Midland miner, brought up in a working class environment, Lawrence, for the first time introduced in literature the working man in his everyday life, paying much attention to the depicting of his inner, private world. The working people in Lawrence’s novels are described as respectable, sensible, shrewd men”.

No, she does not go further; instead, she concentrates on the “socially important” authors, as she was obliged to do – K. Mansfield, R. Aldington, A. Cronin. No Woolf, Joyce or Lawrence at that stage!

Liudmila Cortes was born in 1910, to Boris Blagoveshchensky and Evgenia Shostakovskaya. The 1917 revolution meant that the aristocratic family would be repressed. So, they fled Russia, left St Petersburg and went through Finland to Italy, where the head of the family worked at a Ford factory. Lyudmila went to school in Switzerland. Then, they moved to Chili, where she worked as a secretary in the British Embassy.

Lyudmila married Alberto Cortes. They had 4 children, including the great Belarusian composer and director of the Belarusian Opera theatre Sergey Cortes.

Their family life turned out a failure, and the Shostakovskys (LP’s parents, she and her children moved to Argentine). The husband of the LP’s elder daughter was a member of the Communist Party of Argentine; the Shostakovskys shared the communist ideas; they were persecuted; they had a quasi-legal status; and they were in communication with the Soviet diplomatic mission staff. When, after Stalin’s death, the USSR began to encourage immigrants to come back, the Shostakovskys decided to return, but they were not allowed to live in Moscow or Leningrad. They opted for Minsk and provided with accommodation there. The family was meticulously robbed in the hunger-stricken and ruined post-war Minsk; their bags were lost at the customs. The Shostakovskys bore up well the first happy meeting with the home country, and managed to integrate into the country’s life. Lyudmila Pavlovna Kortes-Shostakovskaya began to teach foreign languages in Minsk University.

In the late 60s and through the 1970s, renowned Russian scholars and professors lived under the pressure of ideology, and therefore literary criticism, meant to shed light on the work of certain writers, was aligned with the main ideological postulates. Scholars HAD to abide, or no publication would be permitted. N.P. Mikhalskaya in her 1960-1970-s articles wrote prolifically and deeply about Lawrence’s creative art. However, she was obliged to insert a phrase.

Like “The scheme of human relations created by Lawrence which is repeated obsessively in each of his novels and claims to be the only reality in existence dims the truth of live and perverts the real meaning of human relations … Lawrence was walking the wrong path a priori… Like other modernists, Lawrence isolates his characters from life and releases himself from the need to analyse social conditions of their existence … he uses trumped up symbols … he criticizes the capitalist civilization in The Rainbow … he was far away indeed from the social and political struggle of his time … And though he would sometimes express his wish to join the revolutionary forces, his ideas about their real nature were most distorted. He looked for their sources not in the progressive movements of the epoch, not in the struggle of the proletariat, but in the primeval power of instincts … the frank eroticism of Lady Chatterley’s Lover removes this novel out of truly artistic literature”.

Then, with the year 1986 and Perestroika, which meant reconstruction of the society and liberation, unheard of freedom of expression, the vector changed the direction for the opposite in Mikhalskaya’s books from that of 20 years before. When I was looking at those later articles, I marked that the sentences remained unchanged while the evaluative vocabulary was replaced by the opposite! Thus, what had been condemned, was covered in total praise now!

A very apt observation made by N. Reinhold seems helpful here: indeed, Lawrence’s work in the Soviet Union was made use of for specific political and propaganda purposes. Yes, thanks to his working-class origin and fortunate appearance of the characters of the same origin in his works he became available to the readers of the Soviet block countries.

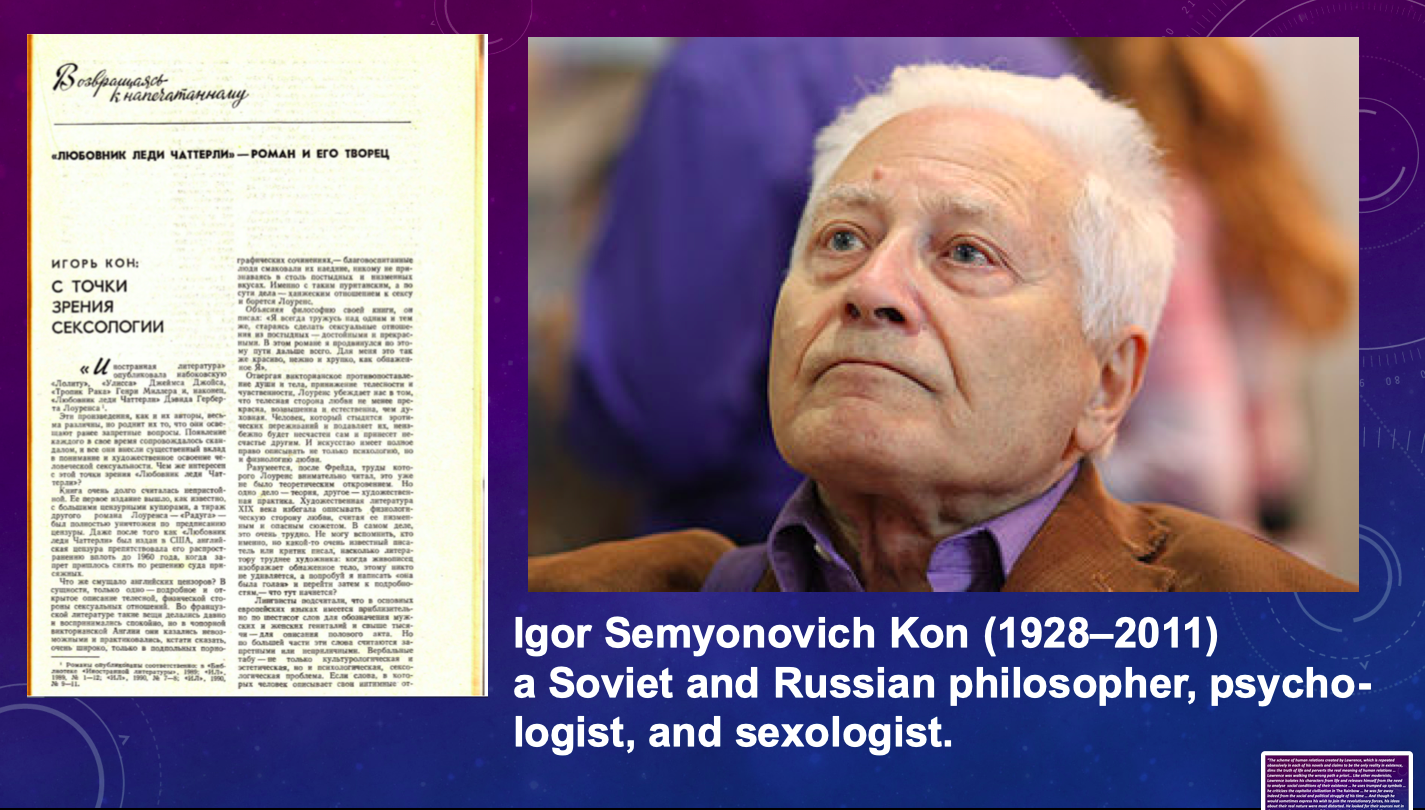

The 1990s is, of course, the period of breakthrough, intellectual and psychological liberation in all spheres of life, including Lawrence’s revival for the new readers. After the seminal publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the 1989 translation, the leading literary journal of the 1980s and 1990s – Foreign Literature – published two “rider” articles: one by a famous sexologist Igor Kon: “Lady Chatterley’s Lover: From the Point of View of Sexology…”; the other – by a critic and scholar N. Paltsev “Lady Chatterley’s Lover: Beyond Sexology”. Paltsev was one of the most progressive scholars and translators with whose contribution the appearance of a collection of Lawrence’s short stories in English, by a Soviet publisher, with his substantial and unbiased introduction and comments was made possible in 1977, thus ushering in the two grand decades of welcoming Lawrence into the Soviet and post-Soviet culture.

A few stories exist in Belarusian translation: “Second Best” is one of them, and it would be curious to learn the motives for selecting this particular one for translating into Belarusian. I may offer a suggestion though.

Only one scholar did research into Lawrence prior to my own – I. Gaiduchenok, and, rather surprisingly, she wrote a book on the philosophical subject of Personality, where, after a more general chapter, she dedicates half of the book to Lawrence’s view of a human personality, pointing out as the major subjects of Lawrence as a philosopher of life, “the sense of connectedness between a human and the universe; … creative aspects of education”. Alongside with these, there are parallels to some thoughts expressed in the writings of Karl Marx!!!

With all that, Lawrence was now firmly rooted in the university curricula. In particular, the novels Sons and Lovers and Lady Chatterley’s Lover were on the students’ obligatory reading lists. The professors tried hard to provide methodology and illustrative material for the students. In the resource centres they would hang some rather rough photographs of the world writers, as in the 1980s the general economic crisis did not allow for any such luxuries as printed posters or anything. And Lawrence’s portrait was duly placed alongside Shakespeare and Dickens.

However, it did not remain there for long: it was stolen. The replacement was provided, but the same destiny awaited that copy as well: the portrait kept disappearing from the wall of the English Centre at the Linguistic University several times, until with better technical and material facilities, a new larger and solid picture was obtained. It remains a mystery to this day why would students want Lawrence’s photograph of poor quality copied from God knows where…. I like to think it was their genuine love!

With time, however, the novelty and freshness of perception of Lawrence’s once revolutionary artistic achievements lost their acuteness. Students of the early 2010s are not so easy to be shocked or even surprised. But even with that, there was one student saying she had had to go the priest for the confession after reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover (which she simply had to do in order to pass her literature exam), and the other refused to read saying it was against her religious convictions…

When Russian journalists write about Lawrence, one never stops being surprised how many distortions and self-invented “facts” they present to the readers. As a curious example, let me refer to an article, published by the Radio Freedom media outlet (2006) by Marina Efimova. It tells about the trend in contemporary critical revival of the authors of the previous centuries. The journalist gives Lawrence’s first name in a very curious transliteration and spells titles of Lawrence’s novels in Russian in her own translation, never caring to look them up: by 2006, almost all major novels had already appeared in Russian translation (except for Women in Love, which was to come out in Russian for the first time only in 2007). One biographical “mis-reference” is likely to create an “alternative” biography of the writer – if you know what I mean; literally, the journalist writes: “In 1914, in his native Cornwall, Lawrence was not allowed into decent houses, because he had swiped a respectable professor’s wife. In 1915, a Cornwall magistrate ordered to destroy all the copies of The Rainbow”.

What is also bewildering in this essay, is that its author makes references to John Worthen’s book D.H. Lawrence: The Life of an Outsider. Moreover, she seems to cherish populist rumours more than she really trusts the eminent biographer and critic, noting that John Worthen “is trying to blanch over his hero”.

English Language teachers use Lawrence’s texts for mastering English both at universities and schools. However, what may be quite curious, is the choice of those texts and learning purposes. Besides short stories, which are convenient of course, and suitable for many purposes, Women in Love was chosen for linguistic study and analysis designed for college students. The authors helpfully provided it with translations, comments, notes and some exercises.

The picture of D.H. Lawrence’s reception in my part of the world would be incomplete without mentioning some influential opinions of the British citizens who spoke or wrote about the writer knowingly addressing the post-Soviet audience, particularly in the 1990s. There were very few D.H.L. scholars, and one important publication by an Oxford teacher Karen Hewitt definitely contributed to what the readers of the philological journal thought about DHL. Some interesting lines from the article (it is paradoxical but I had to translate the English author back into English as the publication was specifically translated from English into Russian for the purpose): “The title is “LCL in the Moscow Metro””.

Karen Hewitt rates the 3 versions as each one becoming more daring and desperate than the previous one, an attempt to teach people how to live. She believed at the time of writing this article that the novel’s place in English literature was not established at all, and associated the historical situation in 1928 (as well as Lawrence’s role in that context), its evocation in the 1960s and the situation in the Russia of the 1990s. Looking at the posters and pictures in the Moscow metro provoked K. Hewitt to observe that it was very much similar to the period when England had no law regulating what was permissible to show to the public, and what was not. (“I have to admit, writes K. H., that the degree of obscenity in your metro is even higher than in our country ever in history, and it is impede on everyone no matter whether they are willing to admire it or not”).

An interesting comparison that this article offers concerns the onset of freedom of speech and weakening of censorship in Russia which appear to the author to be much more drastic and rapid than the revocation of obscenity laws in England in 1960.

Through the whole of the article the motif runs: LCL is the same as the nudity posters on the metro station walls in Moscow. Beware, appeals the article to the readers, there cannot be freedom without consequences. As a result, many questions arise as to the value and impact of the unleashed freedom on the minds of people.

“Lawrence tired hard to make LCL a beautiful book and achieved his purpose in a certain sense. But simultaneously, this is an angry and didactic novel, which persistently preaches what is wrong with human lives and how one should live”.

In due course, I became the D.H. Lawrence scholar in Belarus who completed a PhD course with the dissertation entitled “D.H. Lawrence’s Psychoanalytic Theory and Its Implementation in his Prose” and two books: one as a book monograph version of the thesis (in Russian, by Minsk state Linguistic University Publishing), and the other – Desire for Love: The Secret Longings of the Human Heart in D.H. Lawrence’s Works (CSP, 2012).

Suggested Reading

The Reception of D. H. Lawrence in Europe, eds Christa Jansohn and Dieter Mehl, London: Continuum, 2007

especially

Chapter 10: ‘Russian Culture and the Work of D.H. Lawrence: An Eighty-Year Appropriation’, Natalya Reinhold, 187-97

Chapter 11: ‘A Genius Redivivus: The Czech Reception of D. H. Lawrence’, Anna Grmelová, 198-212

Chapter 12: ‘The Reception of D.H. Lawrence in Bulgaria’, Stefana Roussenova, 222-31

Discussion

Asked whether she taught Lawrence in Belarus, Marina explained that she taught at a linguistic university. It runs literary English courses, in which the students can choose to read Lady Chatterley’s Lover or Sons and Lovers; they tend to read these in both English and Russian. Many of Lawrence’s short stories and poems are used for translation exercises. Sometimes his poems are included on exam papers for commentary. ‘Second Best’ has been translated into Belarussian, and the students are often bewildered by it. When they read Lady Chatterley’s Lover, they are surprised by the open ending, and by the fact that Connie would be prepared to marry down. One student told Marina that, after reading the novel, she had to go to confession. All students find Mellors’ dialect difficult.

In response to a question as to whether Lawrence has been charged with fascism or misogyny in Russia or Belarus, Marina responded that some such charges are made by scholars, but that these perceptions do not exist in the wider readership. The feminist movements in these countries are more political than cultural; they campaign on urgent practical matters such as domestic violence and female nudity in advertising – feminist literary criticism is only just now emerging.

It was pointed out that the Czech reception history was often mediated via the French translations; was there anything similar in the Belarussian reception? Marina suspected that some translations, in particular that of ‘Second Best’, was done with the help of the Russian version; such mediated translation from English into Belarussian is common.

On the subject of film and television adaptations, Marina said that the 1993 BBC Lady Chatterley’s Lover series had been shown in Belarus with Russian dubbing, and that this contributed to the greater popularity of that novel than The Rainbow. She added that she was a student in the late 1980s when Lawrence’s books were purchased by her university library; hers was probably the first Belarussian generation to get a comprehensive view of Lawrence. Now he is seen as a modernist icon. Russian critics like to classify, and Lawrence is definitely on the modernist shelf. In contrast to Karen Hewitt, Marina does not think that there was a strong connection between Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the post-Soviet pornification of society.

Marina was asked more about the different registers of Russian and English taboo language. She said that at home she had two ‘pornographic’ volumes: Zereshennyie Kartinki (curtained pictures), and a selection of pornographic writers, including unpublished writings of Tolstoy and Pushkin. It was possible to publish these for the first time in the 1990s and early 2000s. Bogrov and Litvinova could not use either medical language, or the strong language for which they would be fined. They found the words that would be either dialectical or jargon or slang, in order to avoid this.

She concluded by explaining why she was giving copies of ‘A Chapel and a Hay Hut’ from Twilight in Italy as her handout: ‘The pages you have give you a sense of nature, the spirit and mentality of local peasants […] I found similarities [with the] feelings of reserve of the Belarussian soul – not Slavonic, but close to it.’ For such reasons, she thought that she might offer this essay to her students to translate.

Two other Slavic people present were asked if they had any comments to make on the reception of Lawrence in their countries.

Aleksandar Vasilkov, a Bulgarian, said (and later expanded upon in an email):

‘I did a BA in English in Sofia. There is something I keep finding odd about the curriculum. In the first of four years they present you right away with post-modernism. Then you go back in time to T.S. Eliot and Dubliners and Sons and Lovers – that’s all first semester. In the second year you go back to the Victorian period. The third year is nearly all Shakespeare. The fourth year is American literature all periods. For many years after I graduated in English Philology Lawrence wasn’t even on my radar. Then I did a Masters in another country. My dissertation was on Huxley – so I was bound to discover Lawrence, and did.

Recently I was reading Bulgarian Wikipedia. Women in Love was not translated until about ten years ago; that’s insane. The Plumed Serpent was translated for the first time in 2013; the same person did it and The Rainbow within three years. Sons and Lovers was first translated in 1940.

At the University of Sofia there is a subject called ‘Stylistics’, where students are taught to appreciate the aesthetic qualities of various bits of text (a paragraph per author, let’s say). In the Translation class, similar paragraphs (of high aesthetic quality, and challenging to translate) would have to be translated into Bulgarian. I don’t remember ever coming across a piece by Lawrence in any of these classes, but I did skip a lot of classes so maybe he was there after all? I do remember translating (or attempting to translate) bits from Hemingway, Aldous Huxley and others. I was reminded of all this when I was reading Anthony Burgess’s book on Lawrence, where he talks about his experience of studying English at Manchester and having been given the opening of The Rainbow to analyse/marvel at.

Some thoughts on the Bulgarian reading public under Communist rule (i.e. my father’s generation – people born in the 50s and in their prime during the late 80s/90s): avid readers would have shelves of Bulgarian translations of world classics, especially Russian, German and French. My father is somewhat more exotic – he actually reads Russian fluently and he has read American classics (Twain, Hemingway, Steinbeck, Dreiser, etc.) in Russian translation, which I have always found mind-boggling. So it is rather striking that a person as well-read as my father had not even heard of Lawrence [Liza, at the meeting, confirmed that her Russian father was also well-read and had not heard of Lawrence]. Can we say that for some reason the Communists disliked Lawrence? What would the reason be? The same goes for Huxley (Brave New World and nothing else), but after all Huxley was a far inferior writer in comparison, so I did not give it a second thought.

I think some of the best works of American and English literature of the time managed to slip through the Iron Curtain because they were implicitly or explicitly criticizing Western values. For example, Joseph Heller, whom I’ve read in the original and my father has read in Bulgarian, was a very popular author in Bulgaria in those days, I think precisely because of books like Something Happened, which present Western suburban life as a kind of hell. My mother-in-law has old translations of Stan Barstow and Alan Sillitoe – authors I know nothing about, but I can infer that, since they were translated into Bulgarian, the Communists must have found them harmless or even useful. Again, Lawrence’s absence is very strange.

Finally, I think that one of Lawrence’s main strengths was his writing on nature and the relationship between man and nature. Until the end of WWII, Bulgaria was a largely peasant society. When the Communists took over, the country was transformed into a largely urbanised, industrial society within one generation. Perhaps the pre-1945 Bulgarian reading public (thin as it may have been) would have appreciated the beauty of a novel like The Rainbow or The White Peacock had they been available in translation. After 1945, the country took a turn in a very different direction and themes such as ‘a woman marrying down’ (a nonsensical phrase in a society where everybody is of the same class) just weren’t appealing enough.