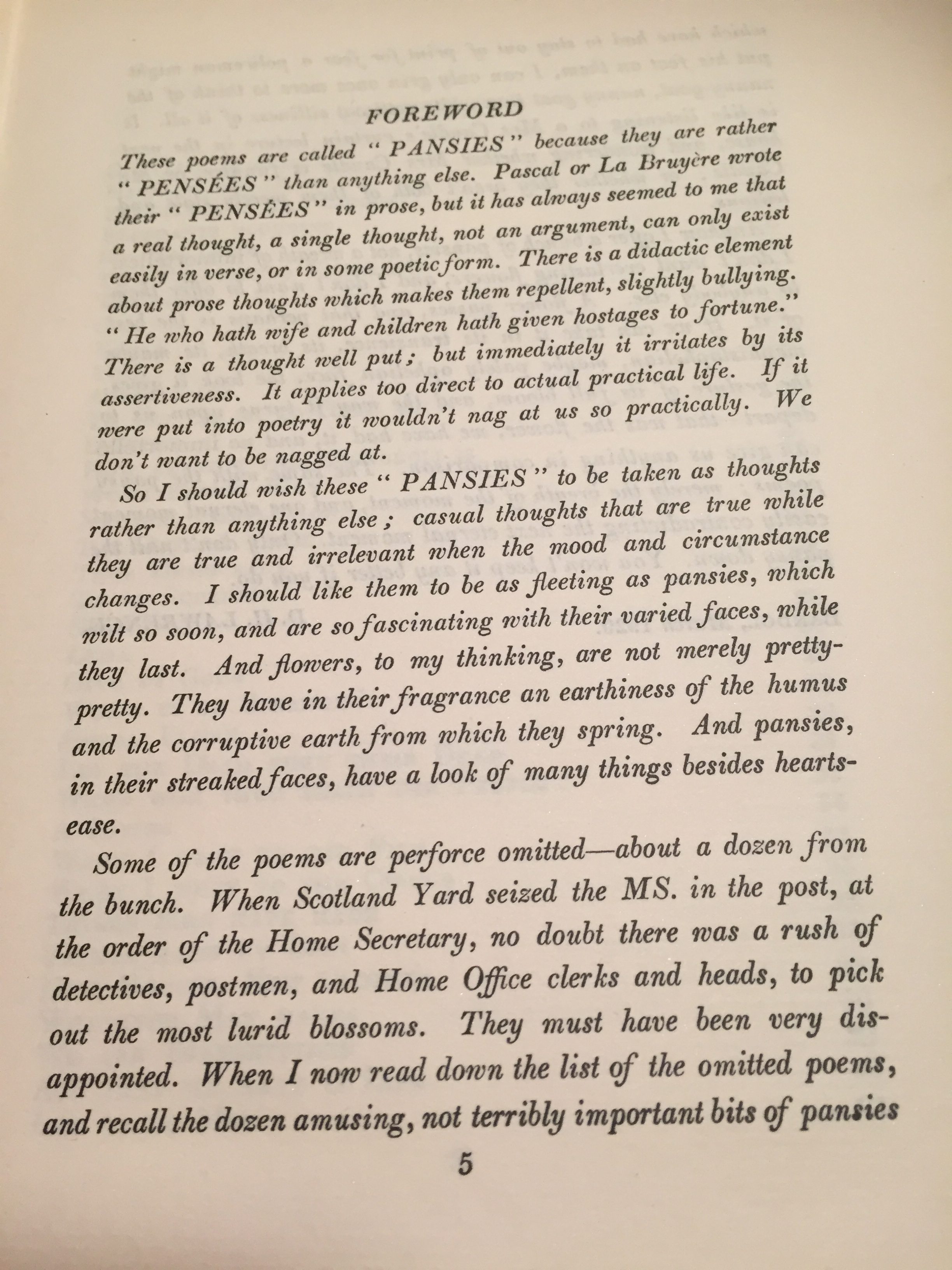

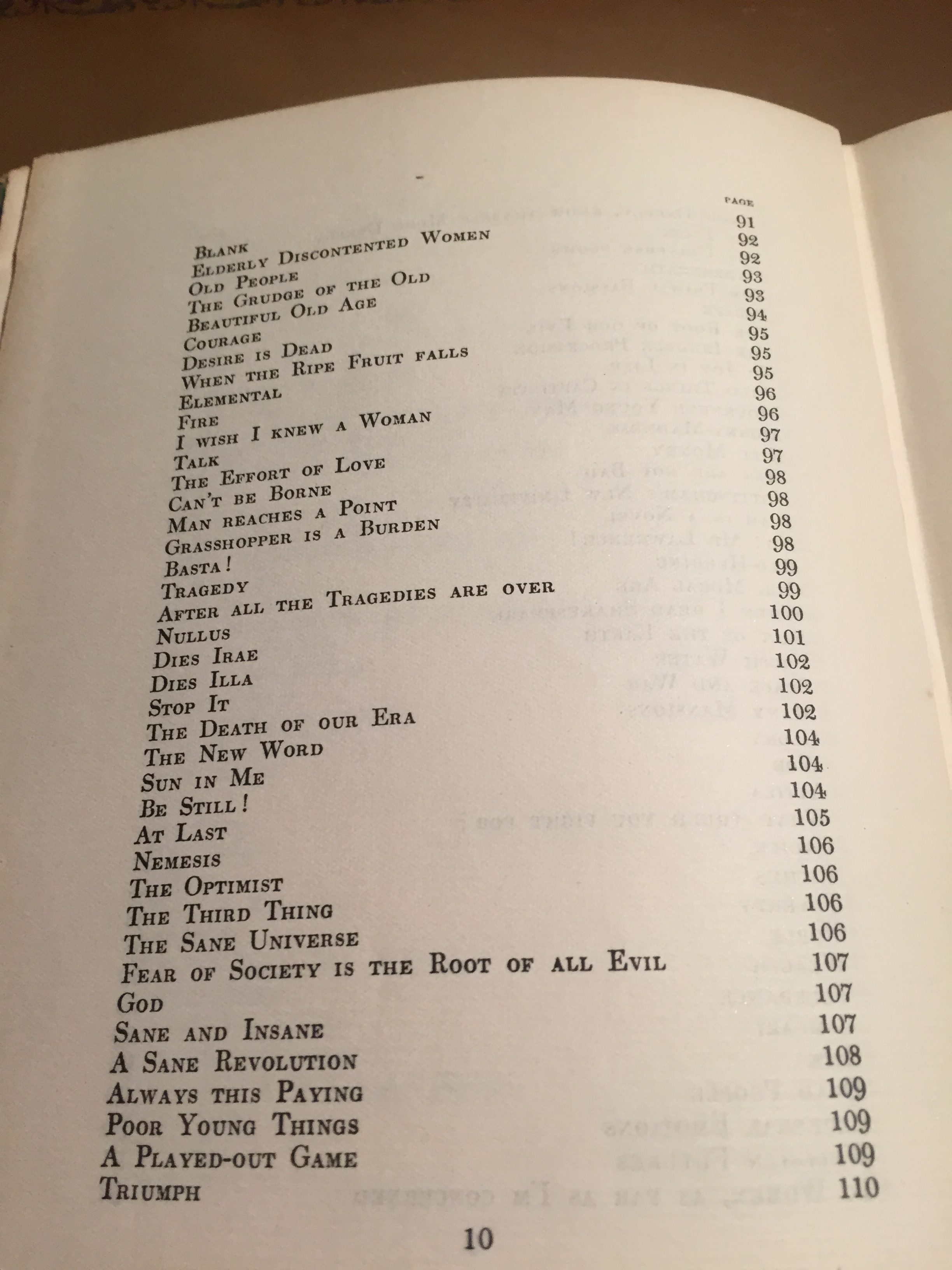

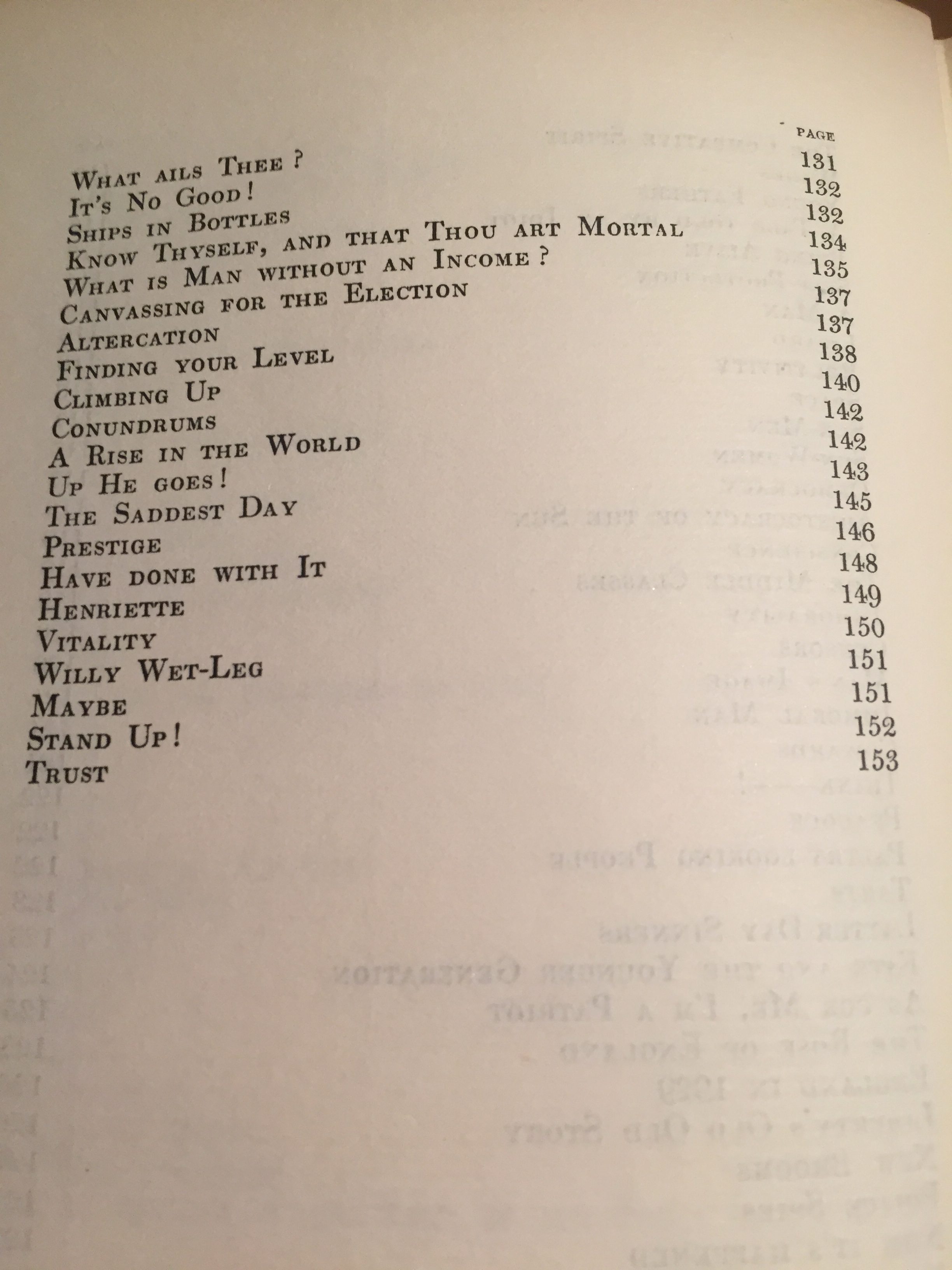

The following paper was delivered at a public colloquium on DH Lawrence’s Poetry held at Eastwood, Nottingham, in April 2017. It concerns the last volume of poetry published in Lawrence’s lifetime, Pansies (1929). The first few pages of the first edition – including Lawrence’s famous ‘Foreword’ – appear below, to give a sense, or a reminder, of the volume.

PANSIES AND POETIC FORM

I’d like to start with an epigraph, even though it was a form that Lawrence didn’t use.

Al Alvarez defends his warmly appreciative criticism of Lawrence’s poetry by saying: ‘‘If my comments are vague and assertive, I can only add another assertion; they have to be.’

And I’d also like to have a Foreword, which was a form that Lawrence did use.

I took inspiration for this talk from Lawrence’s own attitude; when he has had enough of togetherness he wants singularity. People should come together for a tremendous flashing interchange, and then they should draw apart. My little paper is the drawing apart before Lawrence throws himself on God in his death poems, which will be discussed in a later paper today.

The title of this day is ‘As a Poet, is Lawrence a Great Writer of Poetry?’

This specifies that we are to be looking at his poems, not poetic qualities in his other writings; so I thought that I would start by looking at what a poem is, in a question and answer dialogue poem in the manner of Lawrence’s pansy ‘What is he?’:

What is a poem?

A piece of linguistic art that is not in prose, of course.

Yes, but what does that mean?

That everyline ending is meaningful, whereas prose only insists on its line endings once a paragraph.

What about oral poetry, which has no lines?

Its patterns of sounds create units that would cover no more than a line if they were written down.

And how long isa line-if-written-down, since font sizes and page sizes differ?

Good point.

Do not several of Lawrence’s Pansies run over a line, such as‘What is he’ itself, especially in the small format of the first edition?

You always did quibble.

And what about speech, such as ours now?

Well, if we each start a new line, and if we allow for a fewline overruns, such as what I am saying now, then the same applies.

So you are saying that this is a poem?

I suppose that is what I’m saying.

There is in fact no hard distinction between prose and poetry, and the difference is not one of kind but of degree. Line endings are more oftenimportant in poetry than in prose. Poetry takes more frequent breaths. And its meanings residemore than in prose both in sounds and in silences, both in the groupings of words, and the gaps between the groups.

We tend to think of our thought, insofar as it is verbal, as being in prose. Yet do we really think in a continuous stream, like Molly Bloom does for the last fifty pages of Ulysses? Do we not generally pause, hesitate, wool-gather, and therefore have virtual line endings? Is not free verse our mental default? And does it not characterise much of our conversation?

Y’alright?

Alright

You going to the Lawrence poetry day?

You bet.

Yet because we deny this, and see poetry as the exception and prose the rule, those poems that sound most like thought or informal speech are those most likely to be described as prosaic, or not really poetry at all. The reason for this is that when we make the effort of writinganything at all, we do indeed tend to loose the hesitation and diffuseness that characterise the relaxed consciousness. It takes a further effort to retain this quality in written form, or else to do the opposite and impose a regular poetic form.

Lawrence’s poetry went through several clearly distinct phases, two of which he names in his Collected Poemsof 1928. He started with rhyming poems, self-consciously and deliberately poetic, of which the rhymes create the line endings.

He moved on to unrhyming poems, some of which even, as I’ve mentioned, had some multi-line lines. And yet most of the Pansies, I would argue, are still clearly poems, in the sense that they insist on each line ending – however unedited or unbeautiful an expression of thought they may otherwise seem to be. They would, that is, mean differently if they were reformatted as prose.

Sandra Gilbert, in her book Acts of Attention, proves this by printing the the Pansy‘Wages’ first in its original form, and then as prose, and identifying the differences of meaning. In a sense she made life easy for herself in selecting a pansy with such strong line-dictating anaphora:

The first stanza runs:

The wages of work is cash.

The wages of cash is want more cash.

The wages of want more cash is vicious competition.

The wages of vicious competition is – the world we live in.

So let me take a freer-formed pansy, ‘A tale told by an idiot’.

The first stanza is:

Modern life is a tale told by an idiot;

flat-chested, crop-headed, chemicalised women, of indeterminate sex,

and wimbly-wambly young men, of sex still more indetermine,

and hygienic babies in huge hulks of coffin-like perambulators –

The first line stands alone as an announcement. It is the more assertive for turning Macbeth’s two half lines at the tale end of an introverted musing upon hearing of the death of his wife, into a single, extroverted poem-opener, whilst also wrenching Macbeth’s depressive perception out of the sphere of the universal and into the targeted present. The women and men then get a line each, one ontop of the other, with the result of ‘babies’ on the line following. Yet the very separation of the women from the men gives ironic emphasis to the point about their current androgyny.

Around the same time that he was writing this poem, at the very end of 1928, he wrote the essay ‘Give her a Pattern’, which explains in more detail who precisely the idiot telling the tale of modern life is – men, in giving women an abysmal pattern. But the unit of thought in that essay is the sentence, often long and multi-claused. This, for example, does not permit itself to be chopped up into lines:

‘The tragedy is not, even, that men give them such abominable patterns, child-wives, little-boy-baby-face girls, perfect secretaries, noble spouses, self-sacrificing mothers, pure women who bring forth children in virgin coldness, prostitutes who just make themselves low, to please the men: all the atrocious patterns of womenhood that men have supplied to women: patterns all perverted from any real natural fulness of a human being’.

I would not argue that ‘A tale told by an idiot’ is a distinguished poem, but I do argue that it is a poem, in a way that the sentence I have just read, if divided into lines, would not be.

The same is true of the rightly-famous pansy ‘Self-Pity’, even though this is less descriptive and more straightforwardly argumentative:

I never saw a wild thing

sorry for itself.

A small bird will drop frozen dead from a bough

without ever having felt sorry for itself.

Its two sentences could form one and a half lines of prose. But the shortest line, ‘sorry for itself’, could be seen as the little bird which sits on the bough of the longer line beneath, which however also resembles the length of the tumble to the ground when it leaves it: ‘A small bird will drop frozen dead from a bough’. The pity aroused in the reader for the small bird, accentuated by the small lines, is brilliantly contrasted by the poem’s own argument – form here cutting against the thought in a manner which it is poetry’s special power to enact.

I will here share as a personal anecdote the opposite of Sandra Gilbert’s exercise with the pansy. I recently submitted a meditative essay to my college’s student creative writing publication. When I saw the magazine, I was horrified to discover that my piece had been broken up by the editor, who happens to be one of my students, into a poem. I was prepared to stand by it as a moderately successful essay, but I did notwant to see my name over what was a manifestly unsuccessful poem. I have yet to take this up with her..

And it is here that we can see the contrast to ‘A tale told by an idiot’ and ‘Self-pity’, and I think that this true of nearly all but not quite all of the Pansies. ‘Police Spies’, for example, could reassemble itself without loss from two lines into one.

It runs:

Start a system of official spying

and you’ve introduced anarchy into your country.

This does actually resemble a Pascalian pensée– a one-liner such as (in English translation):

Just as we harm the understanding, we harm the feelings also.

But in general Lawrence is right to distinguish his Pansies from Pascal’s pensées, as he does in his various published and draft Forewords and Introductions to the collection, in which he characterises the Pensées as ‘little blocks of prose’, or ‘syllogistic opinions and slices of wisdom […] laid horizontal’.

Whereas, as he said in his Draft Introduction, his‘thoughts sometimes get a poetic way with them. That can’t be helped’.

When Alvarez says of Lawrence’s poetry that ‘In contrast to Eliot’, ‘it was the utterance, what he had to say, which was poetic; not the analysable form and technique’, I would interpret this as meaning amongst other things that his thoughts unfolded themselves in lines – even though he explicitly excludes both Pansies and Nettles from his very positive account of what Lawrence’s poetry is.

Indeed, I find many of the pansies poetic in other ways than merely this, as are Blake’s Proverbs of Hell – for example ‘The nakedness of woman is the work of God’ – proverbs of which Desmond MacCarthy in his review was given ‘a new appreciation’ by the Pansies.

Butif there is a difference between them and prose, there is also a difference from his own earlier poems, and those of other poets of the period.

For example, some of his pansies are imagistic:

This is ‘Elephants Plodding’

Plod! Plod!

And what ages of time

the worn arches of their spines support!

Yet this is not pure imagism, at least not as an image is defined in Ezra Pound’s ‘A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste’ as ‘that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time’. This poem fixates on the temporal, not the spacial dimension that imagism stresses, and rather than seeing a World in a grain of sand, it sees ages in the time between a plod and a plod.

The pansy ‘You’ runs:

You, you don’t know me.

when have your knees ever nipped me

like fire-tongs a live coal

for a minute?

This too seems imagist – the minute-long grip of knees that has never happened is striking enough to suggest it – but is even less so, being addressive, accusatory, questioning and hypothetical.

Of course, the high point of imagism had come fourteen years before the Pansiescame to flower, and pure imagism would never have been Lawrence’s mode in any case. It is too objectivist, distant, self-effacing and unrelational. The addressivity, and complaint about detachment on the part of the addressed that constitutes ‘You’ is far more typical of Lawrence.

But it is more broadly indicative that Lawrence’s later poems never fit neatly into any poetic school, genre or form.

Gilbert points out about one subset of the pansies, ‘Had they been more careful, many could have been […] splenetic haiku’.

Actually, it is questionable how aware Lawrence was of the strict details of the haiku form; their major proponent in England, Ezra Pound, didn’t even write them himself; his imagism was merely influenced by them.

But the way in which, for example, the pansy ‘Cups’ differs from a haiku is again indicative of something typical of Lawrence:

Cups, let them be dark

like globules of night about to plash.

I want to drink out of dark cups that drip down on their feet.

There is the desideratum, the apostrophe, the appeal, and the sensuous alliterative extension of the last line:

I want to drink out of dark cups that drip down on their feet.

Form follows content, and the content, as Lawrence wrote in his first draft introduction, ‘has its roots in good moist humus and the dung that roots love.’

‘Cups’ describe the kind of cup that one would drink out of at the ‘nuptuals’ of Pluto and Persephene of ‘Bavarian Gentians’.

It is of course well-known that Lawrence was less form-orientated than were many of his poetic peers.

Alvarez argued:

I believe it was Eliot who first said that Lawrence wrote only sketches for poems, nothing ever quite finished. In one way there is some truth to this: he was not interested in surface polish; his verse is informal in the conventional sense. Indeed, the tighter the form the more the poet struggles […] there is care, even discipline, but no formal perfection and finish.’

And insofar as this is true of any of his poems, it is true most of all of Pansiesand Nettles. For the former he invented what he called in a letter to the Huxleys: ‘a sort of loose little poem form; Frieda says with joy: real doggerel.’

He stresses in his Draft Introduction to Pansies: ‘It is not offered as a collection of poems. Each little piece is just a thought put down, and it doesn’t pretend to be a half-baked lyric or a melody in American measure.’

In the letter to the Huxleys he rams the point home, that they are ‘meant for pensées, not poetry, especially not lyrical poetry.’

So he wants to take his poems out of the realm of poetry, perhaps in part in order to absolve himself of judgment by its standards – on which standards it was indeed harshly judged.

The contemporary reviewer Louis Untermeyer felt that the ‘abrupt change of style’ from his previous poems in Pansiesrendered it ‘valueless’ as poetry, even though a ‘new Lawrence’ was emerging in the warnings against maleness being undermined by social or religious inhibition.

Richard Aldington, in his introduction to his edition of Last Poems, said not only that Nettles was bad and trivial, but that Pansies too represented a decline from previous form: ‘All is Lawrence, but Lawrence of the off days.’ And Alvarez states: ‘In this count I am leaving our Pansies and Nettles. Though some of these are good, they were intended primarily as squibs, and even if they have a serious enough edge to their satire, few are particularly memorable as poetry.’

Many critics, myself included, agree with Aldington’s simple assertion:

‘The Last Poems are much better’.

And yet, more than asking to be let off the poetry-critic’s hook is going on in Lawrence’s assertions in his letters and prefaces. He is in effect seeking to create a new genre of poem, or pensée – and this desire to disregard, or transcend, or bust genre is typical of Lawrence, and characterises much of his work that I find most appealing: his literary critical essay on Walt Whitman which starts off in the mode of a Whitman poem before morphing into prose, or his provincial satire Mr Noon,which turns into autobiography in the high Alps and then fizzles out just as the life to report begins to run out.

The pressure of his own life and engagement with life in the largest sense produced these disruptions, as is mirrored by a lesser genius, thought a great writer nonetheless, Geoff Dyer, in his autobiographical-biographical response to Lawrence called Out of Sheer Rage.

Beyond this general point about disrupting form as content dictated, Lawrence specfically valorised the non-monumental.

As Gilbert points out, at the time of writing the Pansies he had become a fan of the ‘casual little wooden temples of the Etruscans’ that were ‘dainty, fragile…evanesent as flowers’. ‘We have reached the stage when we are weary of huge stone erections […] Why has mankind such a craving to be imposed upon? […] Give us things that are alive and flexible, which won’t last too long’.

And yet – he edited his Pansies. The textual variants of the Cambridge edition make this quite clear. All that was required for the expurgated edition that came out in July 1929 was expurgation. But he rewrote the poems several times, changing many more details.

Frieda noted in her introduction to the posthumous Fire and Other Poemsthat although he wrote verse as it came to him, he would work it over for anthologies with great patience. Prose he would rewrite; poems he would tweak.

Part of the process of editing for publication involved curating their order. Although they can at first glance seem to change mood as Lawrence might have done, and therefore to have a diaristic quality, on closer inspection they are clearly arranged, as much as are the sections of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, which more obviously purports to have a diaristic quality. Like Shakespeare’s sonnets, they have been ordered into groups, each of which tackles the same subject or thinks through the same problem.

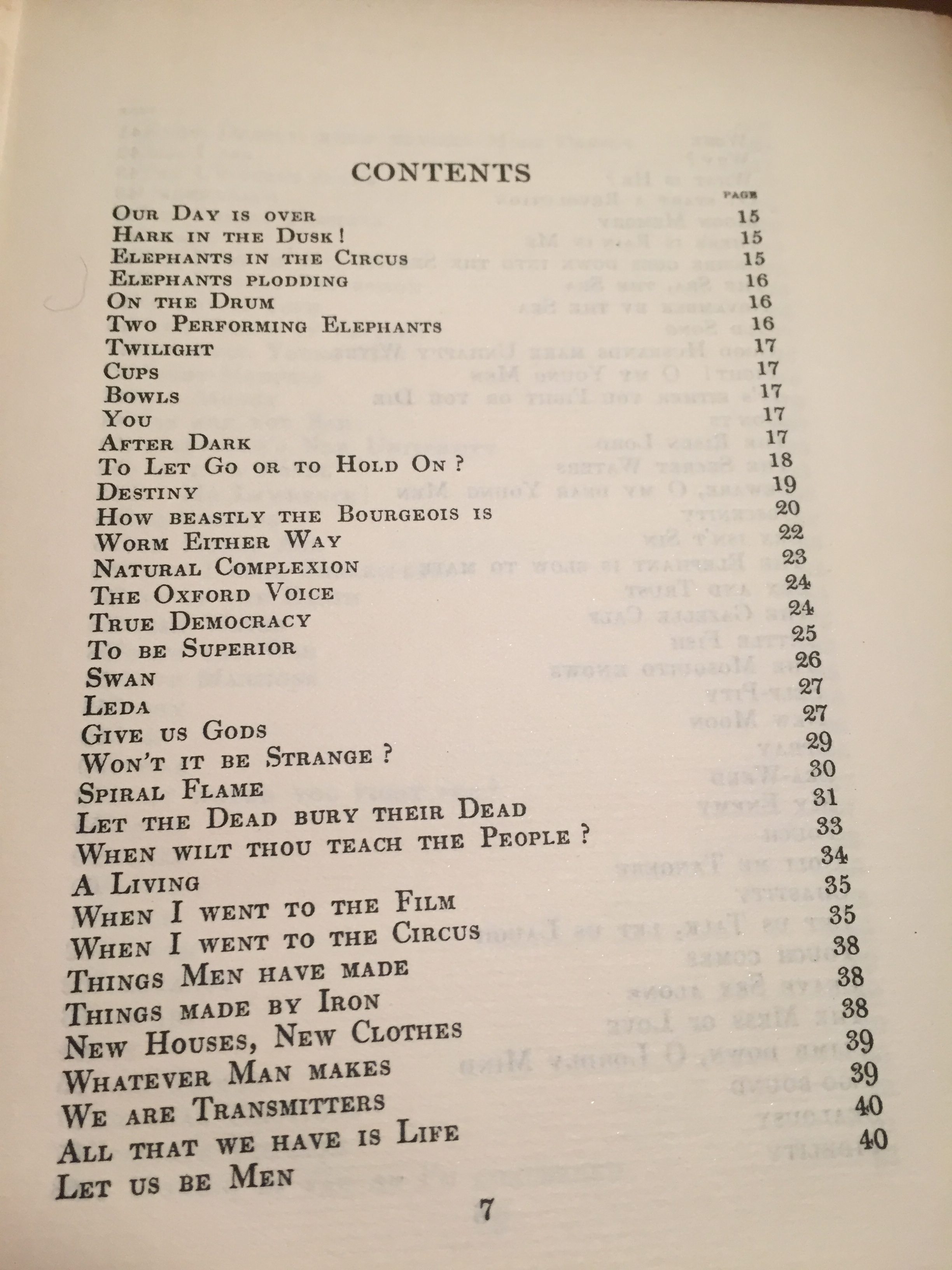

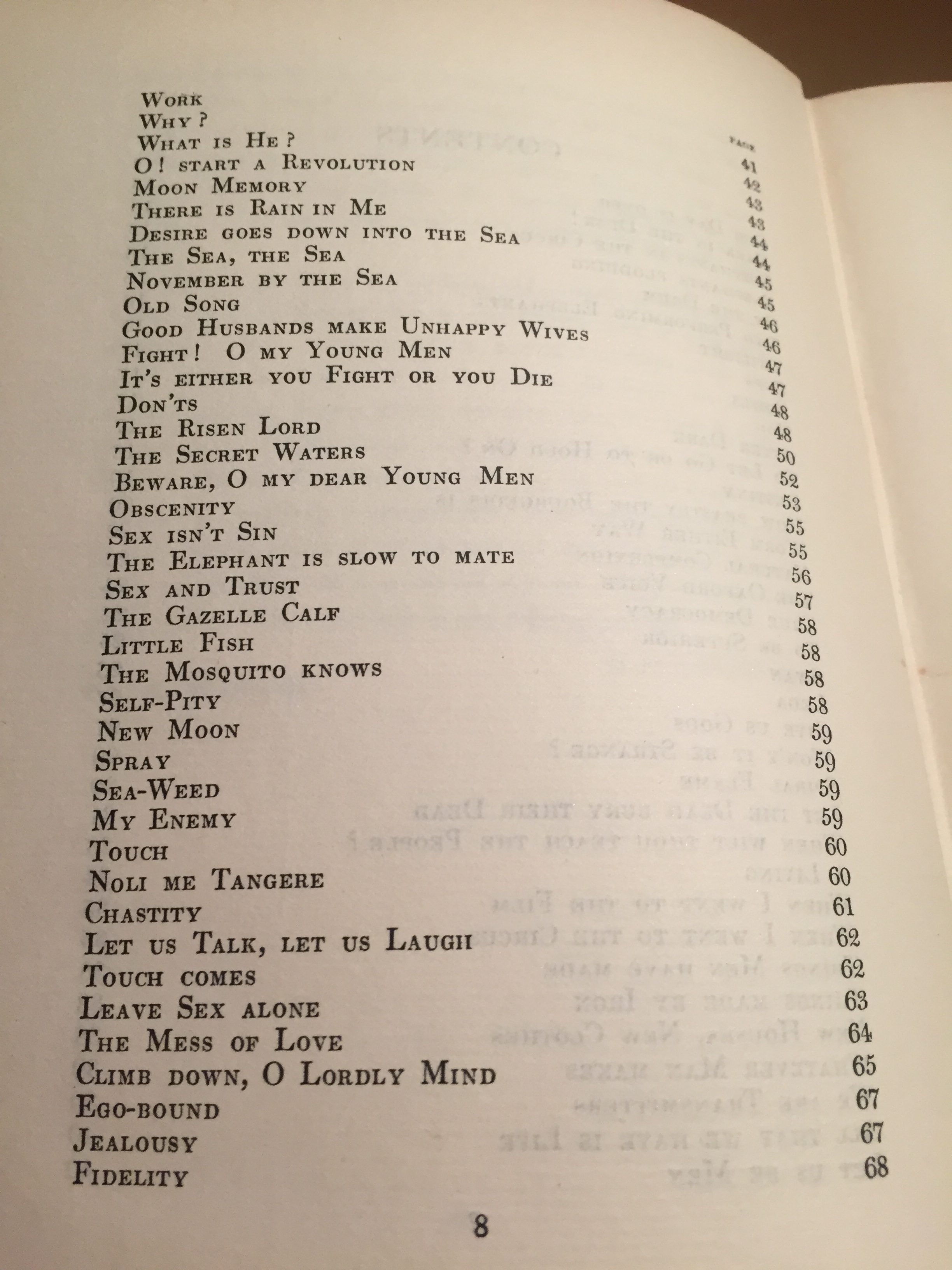

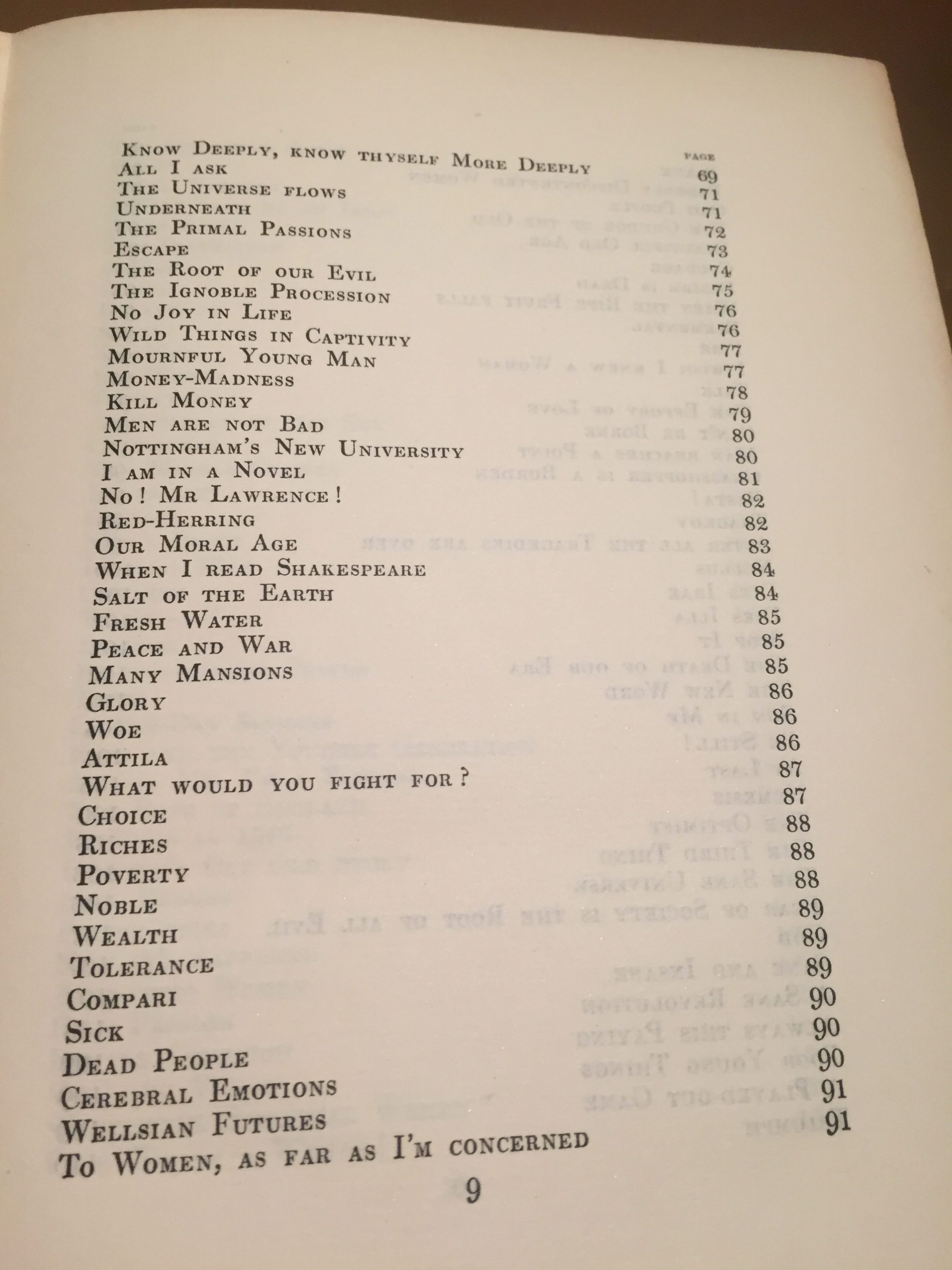

Gilbert lists them as follows: an elephant group, a desire group, an anti-bourgeois group, a swan group, a fidelity group, a work group, a selfishness group, a people group, and one group of poems of ‘prayerful subjectivity’, anticipating the Last Poems.

We might each choose to identify them slightly differently, but you get the idea. They differ between themselves in quite howthey cohere. The desire series works with what Lawrence elsewhere (in his defence of Women in Love) calls a ‘continual, slightly modified repetition.’ The ‘work’ series works through an argument, whilst the ‘people’ series makes what Gilbert calls a ‘miniature variorum’, offering four ways of making the same political point.

Some critics have suggested that some of the poem sequences would work if they were presented instead as a single poem – as In Memoriamin fact is,but Shakespeare’s sonnets are not. Aldington argued this about the Last Poems running from ‘The Ship of Death’ to the end of the notebook, and it is of course easier to make this suggestion with free verse than with sonnets, since such verse is freer to begin and end where it chooses.

These groupings do somewhat conflict with the Introduction’s claim that it suits the modern mind better ‘to have its little thoughts trotting down the page like so many separatecreatures, each with a small head and a tail of its own, trotting its own little way’ Or: ‘this is a book of pensées, and each separate pansy is allowed to tip you its own separate wink.’

But he also, in his Draft Introduction, says:

And if there is no system, think of pansies pansily marching one after the other, stiff as wooden soldiers forming fours around a general! It’s enough system for pansies that they all turn to the sun, and droop when they feel like it. I never did like arrangements of tin soldiers, which is what systems of philosophy always seem to me. I prefer the way things arrange themselves to the sun, or turn their backs to the wind.’

In that case, let us imagine that the pansies are scattered, and some groups of them have the sun shining on them, whilst others must turn their backs to the wind.

Or, as the Second Draft Introdcution states:

It suits the modern termper better to have its state of mind made up of apparently irrelevant thoughts that scurry in different directions, yet belong to the same nest.

Perhaps they distribute themselves between several nests.

And in the unused Foreword, the following is particularly applicable to the groups:

They are thoughts, such thoughts as run through the mind and the body today, and disappear and re-appear: separate thoughts which yet hang together in the current of consciousness, and which, taken all together, perhaps make up a complete state of mind. Each one is separate in its own little idea; yet each depends on all the others for its meaning.

The critic Edward Lucie-Smith said of the difference between TS Eliot and Lawrence as poets: ‘Eliot’s poems [such as The Waste Land] seem to be simultaneous; progression is almost lost and we can think of the whole existing simultaniously in the poet’s mind’, whereas ‘Lawrence dramatises the mind’s enounters.’

I think this is right, and would suggest that the ‘mind’s encounters’ are particularly present in the transitions between the groups, which are so much more striking than the transitions between single, relatively unrelated poems in a collection would be. Precisely because the groups have so palpably been arranged, the transitions between them demand attention also.

I would like to look at three of these transitions.

The first is from ‘Hark in the dusk!’ To ‘Elephants in the Circus’:

Hark! in the dusk

voices, gurgling like water

wreathe strong weed round the knees, as the darkness

lifts us off our feet.

As the current

thrusts warm through the loins, so the little one

wildly floats, swirls,

and the flood strikes the belly, and we are gone.

Elephants in the circus

Elephants in the circus

Have aeons of weariness round their eyes.

Yet they sit up

And show vast bellies to the children.

The second is from ‘Destiny’ to ‘How beastly the bourgeois is’:

But if it is thumbs up, and mankind must go on being mankind,

then I am willing to fight, I will roll my sleeves up

and start in.

Only, O destiny

I wish you’d show your hand.

How beastly the bourgeois is-

How beastly the bourgeois is

Especially the male of the species-‘

The third is ‘To be superior’ to ‘Swan’

How nice it is to be superior!

Because really, it’s no use pretending, one issuperior, isn’t one?

I mean people like you and me.-

Quite! I quite agree.

The trouble is, everybody thinks they’re just as superior

as we are; just as superior.-

That’s what’s so boring! people are so boring.

But they can’t really think it, do you think?

At the bottom, they must nowwe are really superior

don’t you think?

don’t you think, really, they know we’re their superiors?-

I couldn’t say.

I’ve never got to the bottom of superiority.

I should like to.’

Swan

Far-off

at the core of space

at the quick of time

beats

and goes still

the great swan upon the waters of all endings

the swan within vast chaos, within the electron.’

[an unscripted close reading of these transitions followed at this point]

In conclusion: there too is poetry – across the gaps, in the transitions, as I argued at my opening to be characteristic of poetry itself.

But the meanings generated are peculiarly not be nailed down, as Lawrence warns us against doing to his Pansiesin his Foreword.

One could make many other interpretations of the transitions than those I have made.

And in this sense the gaps between groups are what Iser called Leere Stellen – empty spaces, where we can get on board.

And this, I would suggest, is a poetry that the more coherent and less distinguished collection Nettles does not have. But nor does one have it in the more explicitly ordered Birds, Beasts and Flowers.

And we know that these spaces were created by invitation, not merely the actual shifts in Lawrence’s poetic thought over time, such as we read in the notebook transcriptions that form the Last Poems, and in this sense we must make sure to read these two late collections differently.

It was this quality to the Pansiesthat the Manchester Guardian review, like many others, failed to appreciate. It apprehended the range of registers, ‘profanities’ ‘flippancies’ ‘travesties of sacred writing’ ‘flaunting of slang and music-hall catchwords’ but deplored the betrayal of the poet’s calling [‘C.P.’]

The reviewer H.J. Davis saw the volume as split between ‘fairly successful doggerel’ and ‘simple lyric beauty, where the whole quality of life at a single moment is intensely felt’, again without seeing beauty in the relation between the two.

So – to return to the question, as a writer of poems, is Lawrence a great poet?

One way is to answer this is on the basis of the best of his individual poems, such as those we are going to be discussing later today, of which only one is a pansy – ‘We are transmitters’.

But Alvarez has a more nuanced approach. He wrote that Lawrence ‘wrote too much verse, like Hardy and Whitman, the two poets who influenced him most. But even his badness is the badness of genius; and there are quite enough good poems to make up for it.’

And Aldington in his introduction to Last Poems argued that: ‘it is wrong to judge Lawrence on single works and obligatory to swallow, or reject, his entire output as one massive literary utterance.’

But not – I have argued -as a ‘solid block of prose stuffily filling square space’, as Lawrence charicatured Pascal’s pensées. Rather, one can sometimes gain as much from reading between the gaps in Lawrence – gaps between poem groups, between drafts, between genres, between mutually-contradictory statements by the same characters – as from what lies between the gaps.

And insofar as creating meaning over gaps is the peculiar province of poetry, I conclude that Lawrence is a great poet.