In my post Reflections on the Death of an Aunt I mentioned an incident in which my aunt was nearly raped by an American occupier of her Rhineland town.

Twenty years later my parents married, almost a decade closer to the War’s end than we are now from the end of the Soviet Union. Impressively, there was no hostility on either family’s side. As someone brought up English, my German family’s war is both familial and strange to me. It prevents illusions about the uniformity of the German uniformed forces, and illustrates the complexity of the moral catastrophe that was Naziism.

THE MOTHER

Ilse and Ursula Heß

Little bear Ursula (b. 1938) arrived only just before the war, in the process winning her mother the bronze Mutterkreuz (Mother Cross) for a fourth child for the Vaterland, although she was probably not conceived with this in mind. For most of the war she lived in her family’s fine house in the wine town of Alzey, which her parents had built when the German economy improved in the early thirties.

The house in Alzey

Her father was usually away. They kept chickens and slaughtered them in the cellar. She and her brother Dieter (1931-1996) played with paper aeroplanes. ‘Where is your plane flying to?’ Dieter asked her. ‘To Germany!’ she said. ‘But we’re Germany’ he corrected her, ‘you can’t drop bombs on us!’ When bombs did drop on them, in 1945, they were evacuated to the countryside in a cart. After the surrender, back in Alzey, Ursula ran to American soldiers for chewing gum. ‘Don’t do that’, Dieter admonished her, ‘they’re the enemy’. My mother remains to this day, in part by virtue of the time and place of her birth, economical, anti-war, anti-nationalist, anti-anti-Semitic, and grateful to the United States not just for the chewing gum but the Marshall Plan.

THE YOUNGEST AUNT

Tante Renate (1928-2012) was an ideal member of Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls): vigorous of body and politics, a committed Nazi and an excellent long-jumper. When her unit was commanded to stop the Amis’ advance on Alzey, that was what she was going to do. She lacked a bicycle; no matter; she borrowed a friend’s. A few miles West of Alzey she developed a puncture; no matter; she wheeled the bike back to the friend and set off again on foot. She rejoined her group, and one day the Amis appeared. They were not quite the risible force that local radio rhetoric had led them to believe. They had, in fact, tanks the like of which they had never seen. They decided that the better part of valour was containment, and retreated, just ahead of the Americans, all the way to Czechoslovakia. There the Americans finally rounded them up, separated the boys from the girls, put the boys in a field and the girls in a gym hall for the night, and discussed what to do with them next. Nothing, turned out to be the answer. The next day they were all told to go home. So it was that pig-tailed, sixteen-year-old Renate set out to walk from Czechoslovakia to Alzey. She seems to have done much of the journey alone. One night she was taken in by a farming family. In the night she needed to use the chamber pot, and found one on top of the wardrobe in her bedroom. Only the following morning did she discover that this bowl was used by the family to store bread to rise overnight; she was duly chased off the premises. From what she has told me, this was the worst that befell her on her odyssey. She cadged a crossing over the Rhine, and arrived home to her relieved and astonished parents, tick-covered, scratched and filthy, some months after the end of the War.

She found an OSS agent in charge of Alzey. He summoned her to him, and asked her about what she had been doing. She stood up very straight and told the OSS agent that if she had her time again, she would do exactly the same a second time. He thought that she needed to cool off. He exiled her from Alzey, and for some months she worked for distant relatives on a farm. There was one job that she particularly detested: once a week, she would have to thoroughly clean the best furniture and porcelain that filled the best parlour that was hardly ever used. Then the French arrived. They took whatever they wanted to, which happened to include all of the hated furniture and porcelain. She rejoiced.

That autumn the schools re-opened, and she slotted back into the system for her last two years of schooling. Word had it that the Americans were not going to allow Germany to re-industrialise, and that the smart thing was to get into agriculture. So she studied viniculture, and later married the vinicultural expert Wilfried, see below.

Renate Knell, born Heß

I don’t know how long it took or how it happened, but her political intensity, rather than diminishing, tracked an arc from the fascist right to the humanitarian left. She founded the Alzey branch of Amnesty International. She became first a local SPD politician, and then, when she found that party too right-wing, an independent. She worked at the ‘Eine Welt’ (One World) shop attached to her church. She helped refugees in Alzey, particularly Eritreans; they often stayed in her house. She lived out the teachings of Christ with vigour, and many cigarettes. She told me her stories of the war with humour and humanity.

Renate Knell c. 1953

THE YOUNGEST AUNT’S FUTURE HUSBAND

The men in Hugo Boss uniforms had come to the village to pick out the likeliest of the local youths. After propounding the career benefits of their line of service, they picked out ‘du’ and ‘du’ and ‘du’ and ‘du’ from the teenaged audience to report the following morning to the SS station in Alzey. One ‘du’ was the gleaming blonde youth Wilfried Knell (b. 1927), who ran home to his father Otto and told him what had occurred. ‘On no account’, said Otto, ‘will you join the SS. But tomorrow you will go to Alzey and join the Wehrmacht.’ Thus it was that Wilfried, like his future wife Renate, was sent Westwards out of Alzey in 1945 to stop the Amis. Being part of a more serious outfit, he fired out of the forest at the advancing war machine. In return he was shot in the knee – one of a remarkable proportion of leg injuries sustained by young Germans at the hands of compassionate Americans and Russians in the last stages of the war (and later at the hands of the East German officers patrolling the Berlin Wall). He was taken to a war hospital run by Germans. One day, the Americans came. Wilfried was terrified. He thought that they would all be killed; that, in his understanding, is what one did with prisoners of war. But the Americans had arrived with good humour and gum. His only complaint was that the German officer in charge of his ward siphoned off the best food and drink for his fellow officers, leaving the rest the watery dregs. One day Wilfried, from his hospital bed, spoke up. The officer took his leg and kicked sideways at the injured knee. He has limped heavily ever since.

But generous post-war provisions to Kriegsverwunderte (war-wounded) included free travel on Germany’s rail network. He later married Renate, and supported her in her political and charity work, whilst developing a particular interest in Alzey’s Russian refugees. He speaks Russian fluently, having taught himself, in spare time from his career as a viniculturalist, when he was in his fifties.

Wilfried Knell 1958

Postscript added 12th February 2021. I have just heard from my cousin Christian that Wilfried has died peacefully in his sleep today. He has many years been confined to bed, and has listened to his beloved classical music on the radio. He hardly spoke, but sometimes he would sing softly to the music.

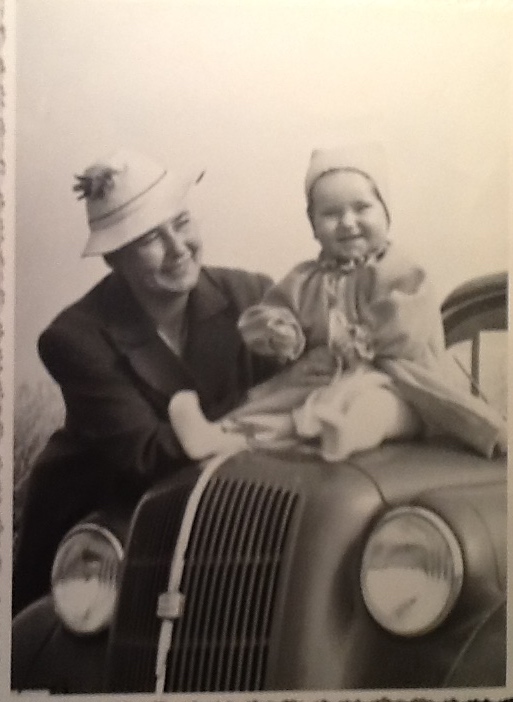

THE GRANDFATHER

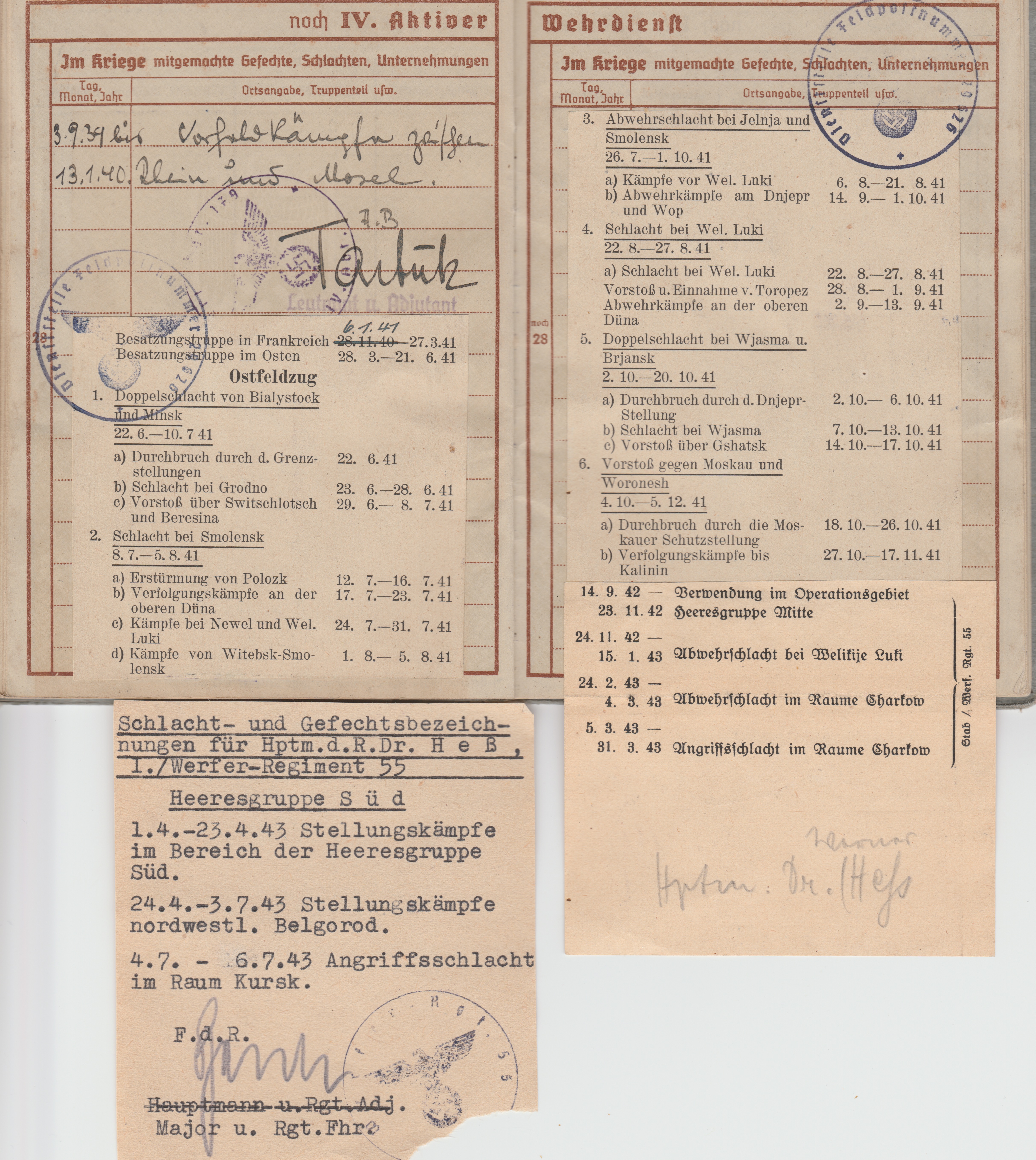

Werner Heß (1899-1973) had the misfortune to be born at a time that made him old enough for the First War and young enough for the Second. For the first he was initially enthusiastic; of the second he disapproved. For the first he was sent to France; for the second he was sent first to France and then to the East. The locations of service listed in his war passport ring a series of deafeningly mournful bells:

Doppelschlacht [twin battles; the word ‘schlacht’ gives us our ‘slaughter’ – rightly, in this case] von Bialystock und Minsk, 22.6-10.7.41.

Schlacht bei Smolensk, 8.7-5.8.41.

Verstoß [assault] gegen Moskau und Woronesh 4.10-5.12.41.

Angriffenschlacht [offensive] im Raum Kursk 4.7-6.7.43.

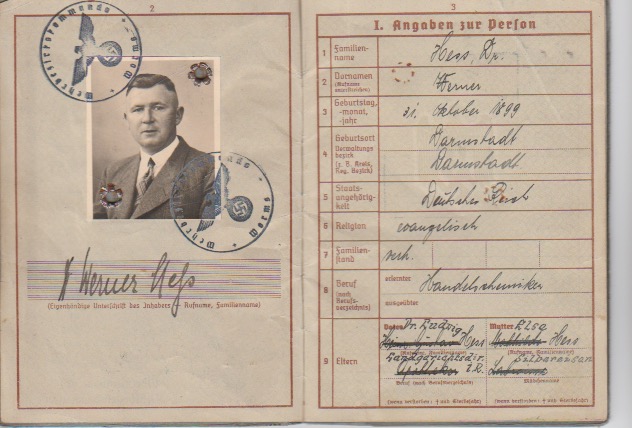

Pages from Werner Heß’s Second World War passport

Finally ‘Entlaffung’ [discharge, in Gothic script], 8. Aug. 1944. He had lost an eye. I only ever knew him, from photographs, as a man with an eye patch. Years later we discovered, amongst piles of family papers at Wilfried and Renate’s home in Alzey, his Nazi Party membership certificate. Nobody had known of it. He was certainly no zealot. He had probably joined to protect his career. Here he is, in Poland, in one of the dark years.

Werner Heß c. 1942, Ostrowo, Poland

THE GRANDMOTHER

Ilse Heß, born Ploch (1903-1990), had married an upright, conventional, kindly man with Burschenschaft (university fraternity) duelling scars in the 1920s. They had danced together a couple of times at a dance hall in Giessen; on the third occasion he walked her home, and asked: ‘wollen wir nicht länger quälen?’ (‘shall we stop messing about?’). This was his marriage proposal, and a happy marriage it was. He was away for much of the war, and Ilse looked after the children and growing number of people billeted in their house, having been bombed out. Her own parents’ house in Giessen was destroyed. When gold was requisitioned for the war effort, she took all of her gold Schmuck (jewellery) to the Alzey station. One of the pieces was a gold snake bracelet with ruby eyes, which wound round and about the wrist. The receiving officer examined it. ‘No’, he said. ‘That’s too beautiful’, and gave it back. Every year, when we visited her for a month in the summer, I would ask her to show it to me; it was my favourite piece of her jewellery.

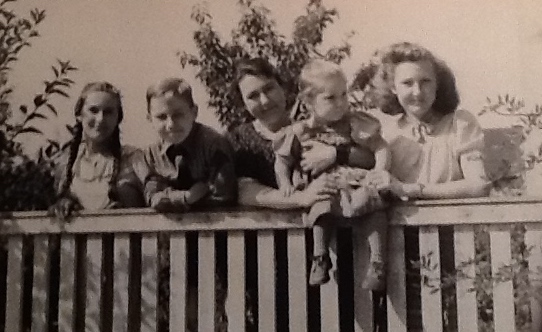

Renate, Dieter, Ilse, Ursula and Inge Heß; anyone who knows me in person will find the full Heß cheeks familiar

Werner occasionally came home on leave. She never told what he said to her. But one day, after one of his visits, she took the children to help her with the harvest. Renate straightened herself up to look over the sweep of Rheinland landscape and declared: ‘Germany is the finest country in the world’. Ilse was silent for a while. Then she said ‘No. It is not so great.’

Dieter, Inge, Renate, Werner, Ursula and Ilse Heß during a period of Werner’s leave

Werner returned home for good in 1944, only to see their daughter Renate disappear into the war herself. When the Americans arrived, it was a shock. Local radio had been describing how valiantly the towns and villages to the West were defending themselves. It was only when it told them how valiantly Alzey was defending itself, that they realised they had been listening to lies.

Some American officers came to occupy their house. Inge, as previously described, was nearly raped. Ilse, alone in a bedroom upstairs, was not so lucky. Werner, who had been locked in the cellar, heard the screams of his wife. He was a wine chemist and the cellar was full of chemicals; he tried to make a bomb which would destroy the house and all who were in it. The Americans released him before any damage, of that kind, was done.

After the war, Ilse had a period of depression. The state paid for her to take a Kur (spa holiday). She looked after her husband until he died in 1973. Now they are buried together, and Renate has joined them in the family grave.

Ilse Heß