Six episodes broadcast from 3.1.2016 onwards on BBC1, 6 hrs 30 in total

Adapter Andrew Davies, Director Tom Harper

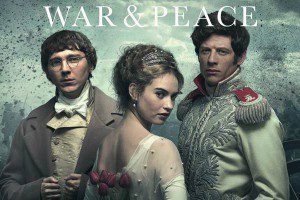

Paul Dano as Pierre, Lily James as Natasha (looking out of character), and James Norton as Andrei

The motion of this adaptation is that of a well-adjusted adult life. You start out finding sex pretty damn important. Then, eventually, gradually or suddenly, your whole being, not just your brain, comes to understand the idea that the most important thing is love.

So the first half of this adaptation was dominated by Tuppence Middleton’s screen-stealing Hélène. She is a far more important, scintillating and sulpherous character than in the novel (and far better played than in Sergei Bondarchuk’s epic 1972 Soviet adaptation). Her incest with her brother isn’t justified by the text, but it sets the tone of this half. Here we are less in the St Petersburg of War and Peace than in that of Anna Karenina, or the Versailles of Liaisons Dangereuses (written and set only two decades before War and Peace’s action) – both the latter being fin-de-siècle, fin-de-regime novels where everyone has affairs, and the ball-rooms and opera-houses drip with sexuality. Anatole approaches the virginal Natasha rather like the Vicomte de Valmont approaches Cécile de Volanges; and both are very willing to be taught. Even the teenaged Nikolai gets a few prostitutes thrown in along the way.

Callum Turner and Tupenny Middleton (bizarrely in art-deco jewellery)

as Anatole and Hélène Kuragin/a

But likeability wins out in this very likeable adaptation. The Sexy Evil Ones (Hélène and Anatole) and the Saturnine One (Andrei) die, so that the Nice Ones (Natasha and Pierre) can marry. Nikolai falls in love with Someone Plain but Good (Masha). The only muck-up in the moral economy is that The Good-if-occasionally-tetchy Faithful One (Sonia) is left without a partner. But she gets to share in a sun-drenched, tear-jerking dinner à l’herbe at the end, so it’s not too bad.

This is a Happier Ending than Tolstoy gives, where everything is far more complex, and the characters are to a greater degree engaged with the kind of ideas that take centre-stage in the narrator’s thirty-six page concluding monologue on the philosophy of history.

Interesting, then, that several English critics commented on how death-filled and dour the final episode was.

I was reminded of Virginia Woolf’s 1925 generalisations about the differences between Russian and English fiction (in The Common Reader). Basically, the Russians, and not the English, do Soul. ‘It is the saint in them which confounds us with a feeling of our own irreligious triviality, and turns so many of our famous novels to tinsel and trickery. The conclusions of the Russian mind, thus comprehensive and compassionate, are inevitably, perhaps, of the utmost sadness. More accurately indeed we might speak of the inconclusiveness of the Russian mind. It is the sense that there is no answer, that if honestly examined life presents question after question which must be left to sound on and on after the story is over in hopeless interrogation that fills us with a deep, and finally it may be with a resentful, despair. They are right perhaps; unquestionably they see further than we do and without our gross impediments of vision. But perhaps we see something that escapes them, or why should this voice of protest mix itself with our gloom? The voice of protest is the voice of another and an ancient civilisation which seems to have bred in us the instinct to enjoy and fight rather than to suffer and understand.’

This adaptation demonstrates the English will to enjoy. Jim Broadbent’s Count Bolkonsky is one that we can enjoy more than Tolstoy’s, or that of most adaptations. We are little taxed by complex or tormented thought, even though this adaptation retains what most of them cut – Pierre’s period of Freemasonry. Where Tolstoy’s characters think, or his narrator thinks about them, this adaptation has nature shots, during which we can do some thinking of our own if we want to. We also have a more comfortable distance in time than did Tolstoy – who had faught in the Crimean War – from the events described. Whatever fresh horrors the military-industrial complex has invented in the meantime, we at least no longer send men marching into canon-fire, or into the insanity of the Duel. Finally, the ending says, whatever has happened, Life Goes On. Simpler than poor, complex, soon-to-have-a-nervous-breakdown Tolstoy, this is a fine, sunny, and generous gift from the BBC to the world.