Report of the Twenty-Third Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Jane and Dudley Nichols

Walking Literary Limpsfield Chart

Saturday, 2nd July 2022, late morning until late afternoon

In person

In and near Limpsfield Chart, Kent, UK

ATTENDERS

Jane and Dudley Nichols, David and Genevieve Ellis, Alan Wilson, James Walker, Catherine Brown

INTRODUCTION

It had originally been the ambition of the London Lawrence Group to have in-person meetings in London and the South of England for members who find it hard to reach meetings in Eastwood midweek. During and since the Covid-19 pandemic, meetings of both the Eastwood-based D.H. Lawrence Society and its London-based offshoot have been available on Zoom, but it remains the case that once or twice a year London Lawrence Group members meet in person to explore places of Lawrencian interest. Jane and Dudley Nichols kindly offered to create and lead a literary walking tour in the environs of the Cearne, home of Constance and Edward Garnett, and in July 2022 – having been twice postponed by the pandemic itself – this tour finally took place. The write-up is by fellow attender and Lawrencian colleague James Walker.

David Ellis reading one of Lawrence’s poems at the bottom of the Cearne, overlooking the Weald.

On the 2 July, I [James Walker] joined Catherine Brown, David and Genevieve Ellis, and Alan Wilson for a walking tour of Limpsfield Chart under the expert tutelage of Dudley and Jane Nichols. Dudley is the nephew of Louie Burrows, Lawrence’s former fiancé (December 1910 until February1912), back from that strange period of his life when he briefly assumed the role of lothario. The trip was arranged in collaboration with the London Group of the D.H. Lawrence Society.

We set off from Limpsfield Chart, right in the heart of the Surrey countryside, and meandered through ancient woodland to uncover homes of influential cultural figures. This included the home of Sidney Olivier (1859 – 1943), Governor of Jamaica and Secretary of State for India in the first government of Ramsay MacDonald. He was also the uncle of Laurence Olivier. But of greater interest were his four daughters Margery (1886 – 1974), Brynhild (1887 – 1935), Daphne (1889 – 1950), and Noël (1892 -1969).

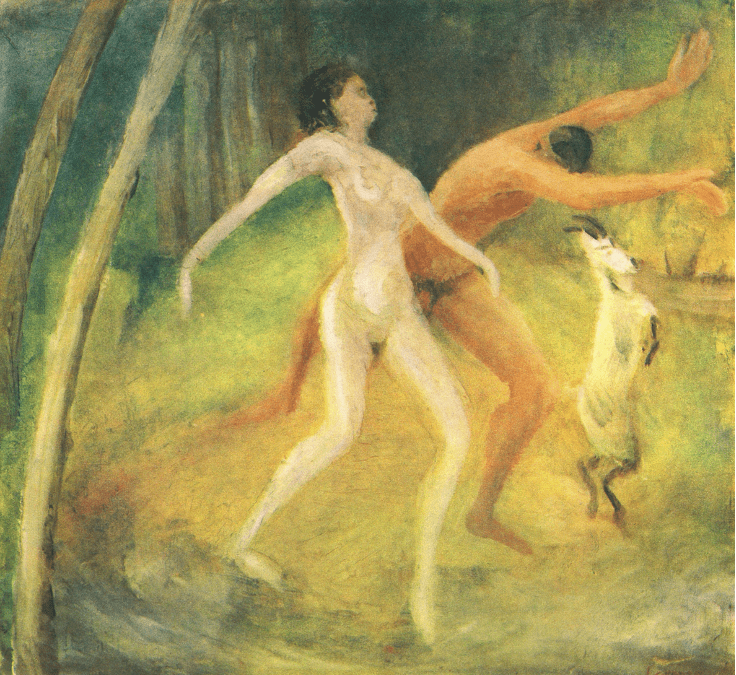

These enigmatic ‘noble savages’ lived life to the max; skinny dipping with the Bloomsburys, marching the suffrage cause, and embracing a bohemian outdoor lifestyle. From their hidden den in the woods, they were more interested in discussing land reform and secularism than pursuing sexual gratification. Virginia Woolf half-mockingly labelled them ‘Neo-Pagans.’ Mostly Cambridge educated, the teenage sisters made a future pact to meet up in Basel, Switzerland on 1 May 1933, where they would vanish ‘from the knowledge of men forever’ and carve out a ‘new world’ together[i]. They didn’t. But their intentions were honourable, and symptomatic of others trying to cope with the changes brought about by modernity, industrialisation and war.

Their mother, Margaret, relocated the family from London to Limpsfield in the 1890s after embracing Edward Carpenter’s principles of the ‘Simple Life[ii]’. Carpenter, an advocate of ‘spiritual democracy’ as well as an early gay rights activist, would later be an influence on Lawrence’s ideas of sexual liberation[iii]. Here they joined a community of progressive Fabian intellectuals where home-schooling and flouting of social conventions was the norm. Neighbours included Edward Pease (1857 –1955) who helped form the Fabian Society on 4 January 1884 and J.A. Hobson (1858 –1940), the economist and social scientist. But what really made this area such fertile ground for activism was the presence of Russian anarchists and exiled writers, most of whom had a link to Edward and Constance Garnett, the main reason for our visit.

Before visiting the Garnett’s family home, we stopped for lunch at the Carpenter’s Arms, a cosy country pub dating back to the 1800s. Mary Soames, the youngest daughter of Winston and Clementine Churchill, remembers the pub fondly in her 2011 memoir as a ‘fruitful recruiting ground’ to help with the yearly Nativity play[iv]. We discovered we had all recently reread The White Peacock (1911), whose floral descriptions I imagine would have appealed to the Arcadian desires of the Olivier sisters as well as fashion designer Laura Ashley, whose curtains adorned the walls of the new Church Hall in 1960 – Ashley taught at the Sunday school.

Once fed, we made our way to the Cearne, home of Edward and Constance Garnett from 1896. On route we passed the home of Constance Garnett’s sister, Grace. Elsie and Ford Maddox Hueffer lived here during 1898/99. As we enjoy the tour and walk freely through open space it is worth remembering that Hueffer suffered from agoraphobia between 1903-06. ‘The memory of those years’ he wrote ‘is of one uninterrupted mental agony.[v]’

Hueffer played an important role in Lawrence’s development as a writer though Lawrence would later observe Hueffer ‘left me to paddle my own canoe. I very nearly wrecked it and did for myself. Edward Garnett, like a good angel, fished me out.[vi]’

Garnett and Hueffer had a strained relationship with different visions for the role of Lawrence as well as literature in general. While a reader at Unwin, Garnett, then eighteen, had recommended Hueffer’s first book, The Brown Owl (1891) for publication as part of Unwin’s ‘Children’s Library’ series[vii]. Garnett was ruthless with his criticism. Olive Garnett, Edward’s sister, recalled in her diary some damning feedback on a biography Hueffer was working on: ‘German – cumbrous – slovenly – vague – will generalise about things of which he knows nothing.[viii]’ Ouch. The rented cottage is where Garnett introduced Hueffer to Joseph Conrad. The two would collaborate on novels and a novella together, but that’s another story.

The shed at the bottom of the Cearne.

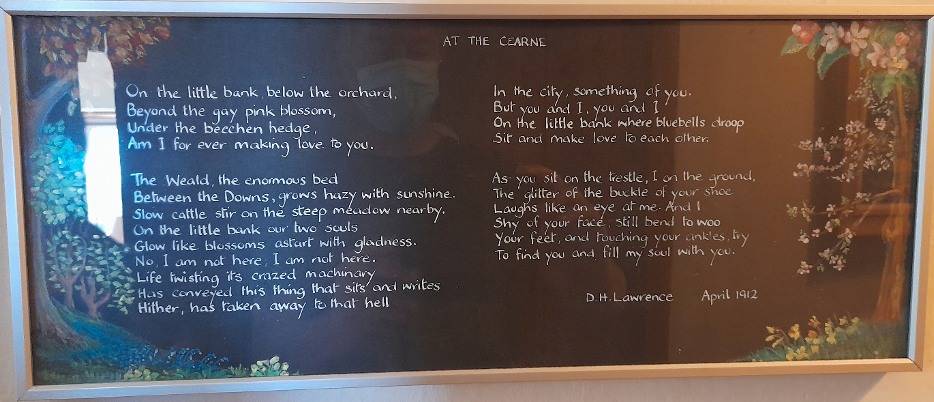

The Garnett’s home, the Cearne, is accessed via a wooded path and sits snuggly above the Weald, an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and South Downs. At the bottom of the sloping garden is a rickety old shed where Lawrence sat and composed poems during his visits, some of which we recited. One of these poems, the aptly named ‘At the Cearne,’ has been illustrated and is framed inside the stone cottage on the upstairs hall, near the bedroom Lawrence and Frieda stayed in. The current owners are well versed on the history of the cottage and were happy to share stories that had been passed on, as well as providing books and articles detailing the history of the home and its many guests.

The illustration of Lawrence’s poem ‘At the Cearne’.

Edward Garnett (5 January 1868 – 19 February 1937) was a writer, editor and critic who started life at T. Fisher Unwin (1887–99) at the age of nineteen but was quickly promoted as a reader. One of his most significant contributions was helping to launch Unwin’s ‘Pseudonym Library’ series (1890–6) which encouraged unknown writers to submit manuscripts. ‘When the author became better known and wanted to claim credit for the work,’ writes Analise Grice, ‘the writer’s identity could be revealed by a press interview or review, which sparked further interest in the volume.[ix]’ Garnett had a brief spell at Heinemann (1900-01) before moving to Duckworth (1901-15), a smaller company that encouraged him to take the initiative.

From August 1911 to November 1914 Garnett provided Lawrence with support on all aspects of his literary career. In addition to finding publication outlets for his plays, novels and poems he even advised which books to review for the English Review[x]. Mark Kinkead-Weekes describes Garnett, who was seventeen years older than Lawrence, as ‘an ideal father-figure[xi]’. This is evident in a letter dated the 17 April 1912 when Lawrence enquired, ‘Why do you take so much trouble for me?[xii]’ He would inscribe Garnett’s copy of Sons and Lovers with: ‘To my friend and protector in love and literature Edward Garnett from the Author.’

One of the things an editor had to protect writers from was falling foul of the various morality lobbying groups that sprung up over the 19th and 20th centuries. One of these was the Circulating Libraries Association, formed on 30 November 1909. Publishers were asked to submit books prior to publication so they could be classified as either satisfactory, doubtful, or objectionable. This hidden form of censorship meant objectionable books were not displayed and were only requested if the public knew of their existence.

Garnet was sensitive to these parameters having experienced censorship as a writer after his 1907 play, The Breaking Point, was refused a licence on the grounds of its alleged indecency.[xiii]’ He would vent his frustration in ‘The Censorship of Public Opinion’, printed in the Fortnightly Review in July 1909, stating that ‘a censorship must necessarily embody and crystallise the ideas and prejudices of the average person; whereas it is the aim of art to transcend those ideas and prejudices[xiv]’. Lawrence couldn’t have been in better hands. However, despite a firm edit, Sons and Lovers would be classified by the Circulating Libraries Association as doubtful.

Lawrence visited the Cearne on the weekend commencing Friday 13 October 1911. The following month he was invited back to meet Scott-James, the literary editor of the Daily News. He would write three dialect ballads at the Cearne (‘The Collier’s Wife’, ‘Whether or Not’ and ‘The Drained Cup’) and Garnett would find a home for his Eastwood-based mining plays. This helped Garnett achieve an ambition he outlined in 1907: ‘We have not had a single novelist of insight to-day who has analysed or mirrored the life of the great manufacturing centres, of the relations of the ‘classes’ to the industrial population, from Birmingham to Newcastle. Consider that from modern fiction we can gather more knowledge about the life of the Kaffirs, the Malays, the Hindus, than about the life of the Yorkshire miners, the Lancashire mill-hands or the Staffordshire ‘Black Country[xv]’.

Although Garnett wanted working class culture to be represented, he was no reductionist. He encouraged Lawrence to develop in other ways, such as challenging perceptions about sexuality. For this reason, Lawrence would acknowledge in 1928 ‘I always look on the Cearne as my jumping-off point into the world.[xvi]’

It should be noted that Garnett’s liberal attitude towards sexuality extended beyond the page; he had an open marriage. As Analise Grice points out: ‘Garnett’s notorious battle with censorship, his high standards for literature, his attempts to become a creative writer, his anti-institutional sentiments, unconventional marital arrangements and his advocacy of the rights of women to claim their sexual independence help us to understand how it was that he and Lawrence got on so well.[xvii]’

Constance Garnett (nee Black, 19 December 1861 – 17 December 1946) married Edward in Brighton on 31 August 1889. In the summer of 1891, then pregnant with their only child, she was introduced to the Russian exile Feliks Volkhovsky, who began teaching her Russian. She would go on to translate 71 volumes of Russian literature into English during her prolific career.

Cottage where Sergei Stepniak lived and commemorative plaque.

Edward was friends with numerous Russian exiles who were either Anarchists or ‘Populists’ (narodniki) or members of secret organisations. Of particular interest was Sergius Stepniak (Kravchinskii), who fled Russia after assassinating the Head of the St Petersburg Secret Police. He was an enigmatic figure and would elicit attention from both Constance and Edward’s sister, Olive[xviii]. We passed by Pastens Cottage from where he frequently visited Constance to assist with translations in their temporary accommodation in neighbouring Froghole during the summer of 1895.

Once in exile, the dissidents put down their weapons and attempted to exert change via more diplomatic channels, focussing on ‘the close ties between the British and Russian royal families’ and hoping ‘the important role of Britain in European politics could help initiate changes in Russia via British public opinion[xix].’ One outcome of this strategy was the formation of the Friends of Russian Freedom[xx] with British socialists. This would be parodied in Ford Maddox Hueffer’s novel The New Humpty-Dumpty (1912), published under his pseudonym of ‘Daniel Chaucer’. Although Hueffer could identify with their struggle, he was aware it came with consequences. Writing in his diary, he observed that ‘thousands of heroic young people whom his (Stepniak) titanic conspiracies sent to die in exile[xxi]’

Garnett believed ‘that the English novel at the turn of the twentieth century was damagingly insular, in dire need of rejuvenation and that salvation was to be found abroad’ and was ‘adamant that the Russians were the only true exemplars. Not only did Garnett send his protégés away to read the Russian masters, he tirelessly promoted their work in his critical columns and wrote several introductions to his wife Constance’s translations.[xxii]’ He had a phenomenal impact on Lawrence at the very beginning of his career, as well as devoting unsurmountable energy to other causes and writers, helping to build a better world with words.

[i] Sarah Watling. Noble Savages: The Olivier Sisters. A Biography. 2019, Oxford University Press.

[ii] Edward Carpenter. England’s Ideal: And Other Essays on Social Subject. 1887.

[iii] Emile Delaveny. D. H. Lawrence and Edward Carpenter: A Study in Edwardian Transition. 1971, New York: Taplinger Publishing Company.

[iv] Mary Soames. A Daughter’s Tale: The Memoir of Winston and Clementine Churchill’s Youngest Child. 2011, Transworld. p.67.

[v] Ford, Ford Madox. Return to Yesterday. Ed. Bill Hutchings. Manchester: Carcanet, 1991. Pp 202-204.

[vi] Letters I, 471.

[vii] Annalise Grice. D. H. Lawrence and the Literary Marketplace: The Early Writings, Edinburgh University Press, 2021. p.107.

[viii] Olive Garnett, diary entry. ‘Saturday 28th’ [September] 1895, in Olive & Stepniak: The Bloomsbury Diary of Olive Garnett 1893-1895, ed. Barry Johnson, Birmingham: Bartletts Press, 1993.

[ix] Analise Grice p. 108.

[x] Ibid: 105.

[xi] Ibid: 104.

[xii] Letters, I, 383.

[xiii] Analise Grice p. 122

[xiv] Edward Garnett. ‘The Censorship of Public Opinion’ (1909) p.137–48.

[xv] Edward Garnett. ‘The Novel of the Week’ (review of Arnold Bennett’s Anna of the Five Towns) (1907): p.642.

[xvi] Letters, VI, p.520.

[xvii] Analise Grice. p.141.

[xviii] Sergius Stepniak and his close relationship to Constance is described in detail by her grandson Richard Garnett in Constance Garnett: A Heroic Life (Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd, 1991)

[xix] Anat Vernitski. ‘The Complexity of Truth: Ford and the Russians’ in Ford Madox Ford’s Literary Contacts, Brill, 2007, p.103.

[xx] Anat Vernitski. ‘Russian Revolutionaries and English Sympathizers in 1890s London: The Case of Olive Garnett and Sergei Stepniak’, Journal of European Studies 35:3 (2005), 299–314.

[xxi] Anat Vernitski. ‘The Complexity of Truth: Ford and the Russians’ in Ford Madox Ford’s Literary Contacts, Brill, 2007, p.104.

[xxii] Helen Smith. ‘Opposing Orbits: Ford, Edward Garnett and the Battle for Conrad’ in Ford Madox Ford’s Literary Contacts, Brill, 2007, p.83.