The following paper was delivered at the (online) 34th annual international D. H. Lawrence Conference ‘Lawrence and the People’ hosted by the University of Nanterre, Paris, in April 2021. This conference was originally to have taken place in person in March 2020, but was delayed by the Coronavirus pandemic. Its Call for Papers ran:

“The people, being subject to the laws, ought to be their author.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, chapter 6.

“Creators were they who created peoples, and hung a faith and a love over them: thus they served life.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, So spake Zarathustra, Chapter 11.

The people is a more or less discreet or threatening presence in Lawrence’s fiction, a kind of collective character with its psychology and narrative function, or a topic for discussion between protagonists. It is also an important theme in the author’s non-fiction, “the political problem of the collective soul” as Gilles Deleuze puts it in his introduction to “Apocalypse.” One immediately thinks of the essay “Education of the People,” but the focus should not be exclusively on this controversial text. “The people,” that of the contemporary working class, is a theme of speculation from Lawrence’s first writings to the last. Strikingly, it is the subject of both Lettie’s letter to the narrator at the end of his first novel, The White Peacock (1911), and of Mellors’ letter at the end of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). Even where Lawrence is tempted to romanticise exotic, primitive, or past peoples untouched by industrialization and modernity, we may perceive oblique references to his own people.

In Kangaroo, the socialist leader Struthers tells Somers insistently, “you’re the son of a working man. You were born of the People,” many Lawrence characters are “of the people,” so was Lawrence. His proximity with the working class in his youth definitely accounts for his lifelong interest in popular culture and the people’s living conditions and, sometimes, for a fleeting touch of nostalgia which never precludes critical distance. Being both an insider and an outsider in relation to the working class people, he never seemed to believe, like the aristocratic Tolstoy, in a possible regeneration through the immersion in the” people or a “turning to the people.” His readings of philosophical works, those of Plato, Locke, Rousseau, Carlyle, Nietzsche, among others, helped him to shape his vision of the relation of the people to authority. His personal change of status, his contacts with other countries, the war and the social upheavals of the period, also contributed to the deepening of his reflection on the people as a sociopolitical entity and to the development of what we may term his social philosophy. Though “the people” is ever present in Lawrence’s writings, he himself was at great pains to define what a people is. When asked to write a play for “A People’s Theatre,” he wondered facetiously about several possible meanings of the term in his “Preface to Touch and Go“: “Not The people: il popolo, le peuple, das Volk […] Plebs, the proletariat […]. What people? Quel peuple donc?” What people in Lawrence? And who does he write for? Both the polysemy of the term and the fact that the writer was himself “of the people” or “from this people” makes for complexity and probably renders these questions to which he responded with characteristic ambivalence more interesting ones.

The following is a non-exclusive list of possible topics of inquiry: Lawrence as a commentator of contemporary social theories, the will of the people, the people and the law, the social structure of primitive and modern societies, ethics and politics, leadership, the sense of superiority, colonized peoples, patriotism, intellectual influences and antagonisms, coherence or evolution of Lawrence’s social philosophy.

It was Rozanov and previously Murry who’d irritated Lawrence by claiming this.

And yet, by the time three years later that Lawrence wrote an introduction to Kot’s translation of the ‘Леге́нда о Вели́ком инквизи́торе’ on his deathbed, he’d changed his mind to the extent that he thought that ‘this story’s perception, ‘once recognised […] will change the course of history’.

For those who don’t know it, Ivan Karamazov tells his brother a story of Christ returning to early sixteenth-century Seville.

The presiding Inquisitor orders Him burned at the stake, to avoid the risk of Him undoing the Church’s correction of His former teachings.

This correction had consisted of removing the burden of freedom of conscience from the masses, and of giving them what Christ had refused to do: miracle, mystery and authority.

It is only when Christ kisses the Inquisitor, having listened to him in silence, that he revokes the death penalty, but still expels Him from Seville.

Ivan’s brother Alyosha, who is a novice monk, listens appalled, but likewise kisses Ivan.

This story, often presented separately from its novel, as when it originally appeared as an instalment in June 1879, or in Blavatsky’s translation of 1881, or Kot’s of 1930, has become something of a theological-political Rorschach test for critics.

Which is why I’d like to try putting Lawrence’s response in the context of others’.

Here are the coordinates:

A large majority of critics consider Dostoevsky to be aligned with Alyosha and against the Inquisitor (whether or not they think Ivan is on the Inquisitor’s side).

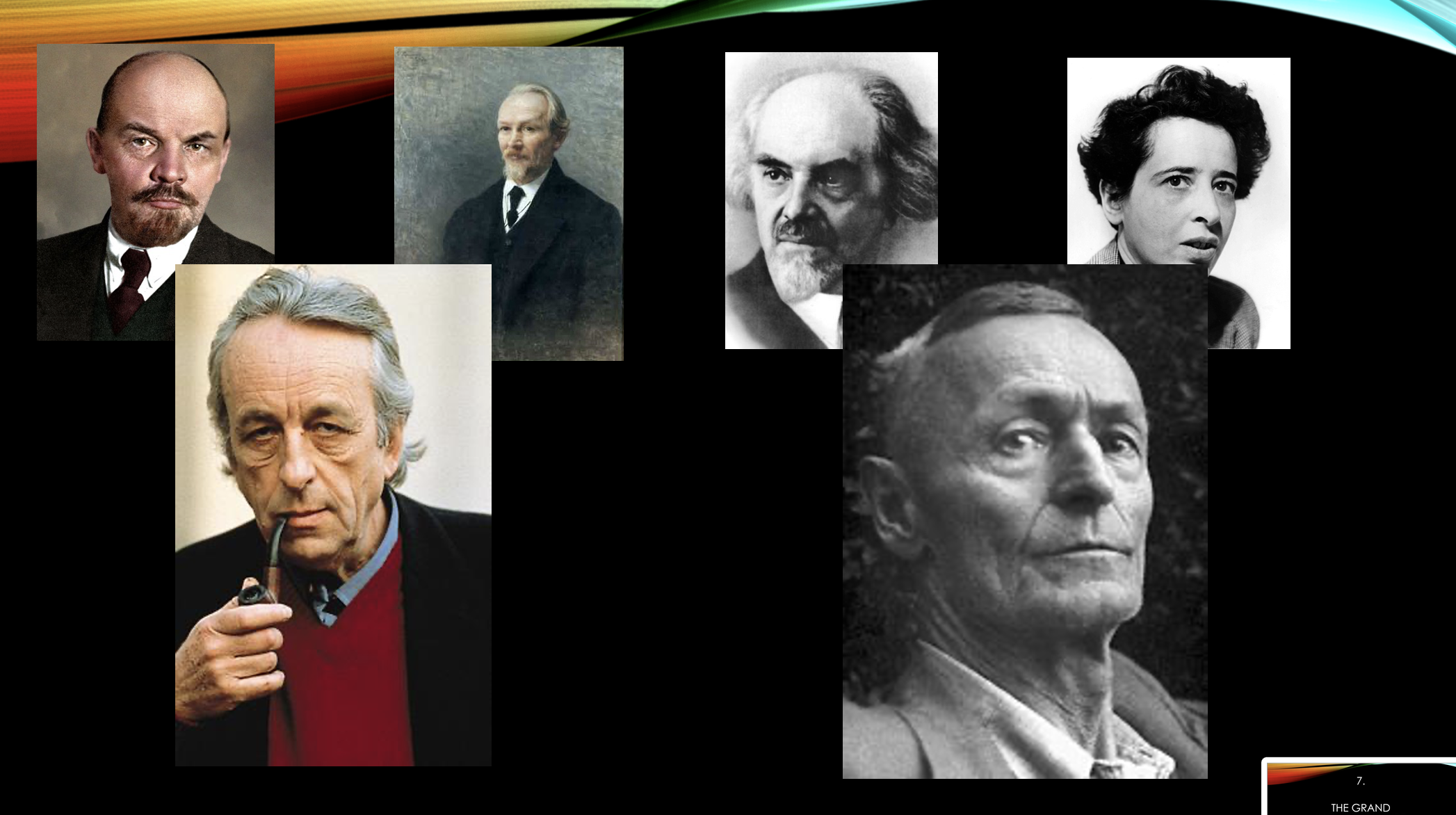

Such critics include Dostoevsky himself in his Writer’s Diary, Blavatsky, Rozanov, Murry, Berdyaev, Huxley, Arendt, Girard, and Chomsky.

A few critics consider Dostoevsky and Ivan to be aligned with the Inquisitor, and because they consider the Inquisitor to be dangerous, they therefore condemn Dostoevsky. Hesse and Camus fall into this category.

A few other critics consider Dostoevsky to be aligned with Alyosha against the Inquisitor, but find things to admire in the Inquisitor, and therefore condemn Dostoevsky. These include Schmitt and Althusser.

A further few think that Dostoevsky is aligned with Ivan and the Inquisitor, and that he is at least partially right to be so. These include Shestov and Merezhkovsky.

And finally, there is a critic who considers Dostoevsky split between alignment to Ivan and Alyosha, and therefore also split on the Inquisitor, but who is himself substantially aligned with the latter. This is Lawrence.

He’s therefore closest in his views to Carl Schmitt, a Catholic political theorist who later became the legal architect of the Third Reich, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, a Tolstoyan neo-Christian who later became so strongly anti-Communist as to support Hitler, Louis Althusser, a structural Marxist philosopher who had supported the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and Lev Shestov, an early twentieth-century Jewish Christian existentialist philosopher of despair.

I’d like to proceed by investigating Lawrence and others’ responses to a series of seven hypotheses raised by the Inquisitor.

First:

The rejection of this idea that men should give their lives to attempt to improve the lives of the masses is found repeatedly in Lawrence’s work.

In ‘The Man Who Died’, written two years before his Introduction, Lawrence corrects Christ by having him learn that he shouldn’t have sacrificed himself to save the masses, but should instead live his own life. And even insofar as this was a critique of his own career to date, his method of preaching in that career had been to let those who had ears to hear, hear; he knew that most would not.

Now the Inquisitor, who at least says he cares for the masses, thinks that Christ didn’t truly do so, because He left them freedom, and its attendant discontents.

And Lawrence in his Introduction shifts from many of his own positions, including distance from Christian philanthropy, by claiming that the Inquisitor ‘is serving the great wholeness of mankind, and in that respect, it is Christianity.’

I should add that the majority of those critics who oppose the Inquisitor also claim allegiance to the masses, but don’t accept the Inquisitor’s second hypothesis, which is that:

Again, the nay-sayers first:

Murry in his 1916 book supported Alyosha who rejects the Inquisitor, describing him as ‘the miracle of the novel’.

Nikolai Berdyaev, a Christian philosopher, wrote in 1935 condemning the Moscow Metropolitan for condemning the theologian Sergei Bulgakov for heterodoxy: ‘For Dostoevsky, authority within religion is of the spirit of the Anti-Christ…And always it is justified thus, just as the Grand Inquisitor did, with being concerned for “these little ones”.

Sartre interpreted Ivan’s invention of the Inquisitor as evidence of his understandable if weak desire to lay down his own freedom, which produced existential anguish. ‘Ivan longs for … the complete removal of the anguish of responsibility – he longs for the type of happiness that only a Grand Inquisitor can provide.’

Camus had a rather different take. In his 1951 book which distinguished dogmatic and counter-productive revolution from non-ideological rebellion in favour of justice, he presented the Inquisitor as someone who’d lost touch with the philanthropic basis of his rebellion, and therefore justified crimes such as burning heretics. Indeed under all revolutionaries who claim to act for the masses, ‘a race of culprits will endlessly shuffle toward an impossible innocence, under the grim regard of the grand inquisitors.’

In 1958 Huxley revisited his 1932 Brave New World and was particularly concerned that young Americans had lost faith in democracy, did not object to censorship, and would consent to oligarchical rule provided their living standards were maintained. He quotes: “In the end,” says the Grand Inquisitor in Dostoevsky’s parable, “they will lay their freedom at our feet and say to us, ‘make us your slaves, but feed us.'”

Arendt’s 1963 analysis of revolution has much in common with Camus. She thinks that the inquisitor has as much lust for power as pity, and that pity in any case does not have the ethical force of compassion.

Girard thought that the story offered a Satanic temptation to critics to read it as supportive of the Inquisitor, but that in so doing it offered Christ-like freedom to its readers, a freedom that was productive of the Dostoevskian underground from which the story had emerged, but which ultimately served God’s greater glory.

As for the Ober-Procurator of the Russian Holy Synod at the time that the story came out, Pobedonostsev, he wrote to his friend Dostoevsky that he was anxious that the Inquisitor be refuted, but that he was not sure ‘What answer can be given to all of these atheistic statements’; ‘‘I just waited – where there will be a rebuff, objection and explanation’.

The irony is that Pobedonostsev, who had opposed the liberation of the serfs and was the intellectual force behind the reaction of the late Russian empire, was after 1879 popularly known as the Grand Inquisitor, and even Torquemada. His nervousness may have been at the voicing of some of his own ideas by a Satan-worshipping atheist Catholic.

So in what spirit, then, did Lawrence support the Inquisitor?

In his 1930 Introduction he adduced evidence of the masses’ craving for miracles, such as radio; mystery, such as spiritualism; and authority: ‘Russia destroyed the Tsar to have Lenin’.

For him ‘If a love of mankind entails accepting the bitter limitation of the mass of men, their inability to distinguish between money and life, then accept the limitation’

Carl Schmitt, who like Pobedonostev was also to attract the soubriquet Inquisitor, in 1923 argued that to Dostoevsky ‘Every power was something evil and inhuman to his fundamentally anarchistic (and that always means atheistic) instinct. In the temporal sphere, the temptation to evil inherent in every power is certainly unceasing. Only in God is the conflict between power and good ultimately resolved. But the desire to escape this conflict by rejecting every earthly power would lead to the worst inhumanity.

There is a dark and prevalent temper that perceives Catholicism’s cold institutionalism as evil and Dostoyevsky’s remote formlessness as true Christianity. That is as superficial as anything on the level of emotion and sentiment’. Lawrence in his Introduction would agree with this, as perhaps also with

Merezhkovsky, who in 1901 argued that Ivan had created a false opposition between ‘two false Christs’. Since the real Christ did miracles, both in the Gospels and in Ivan’s Seville before his arrest, and since he showed considerable concern with providing five thousand people with earthly bread as well as that of heaven, there is little contradiction between Christ and the Inquisitor who purports to correct him. And the denial of miracles, far from being Christlike, belongs to modern scientific atheism.

He wrote this in a book on Dostoevsky and Tolstoy at the time that the latter, with Merezhkovsky’s sympathy, was being excommunicated by Pobedonostev for heresy. But there is in his thinking here an ideal of a holistic, spiritually-nurturing society which he carried forwards into his opposition to Bolshevism and his support for what he perceived to more resemble this in Fascism.

He did not argue that people were in any way limited or foolish in their need for strong leadership.

But the Grand Inquisitor did.

His third hypothesis is that:

On this issue Lawrence, even within his Introduction, vacillates. Late in the essay he asks:

‘Are these three desires [for miracle, mystery and authority] weaknesses? ‘Are they not bound up in our emotions’

‘It is no man’s weakness that he needs someone to bow down to. It is .. his strength, for it puts him into touch with far, far greater life, than if he stood alone.’

This seems, however, to be an afterthought. Most of his essay had been congruent with his statement that: ‘The recognition of the weakness of men has been a common trait in all great, wise rulers of peoples, from the Pharaohs and Darius through the great patient Popes of the early Church right down to the present day. They have known the weakness of men, and felt a certain tenderness. ‘

The Inquisitor’s fourth proposition is that:

Here Lawrence is far clearer. He finds it evidence of ‘ugly perversity’ as well as implausibility on Dostoevsky’s part that he aligned the Inquisitor’s wise spirit with the propensity to torture, since his ‘was not the spirit of the Spanish Inquisition …[which was] not Catholic at all..The Spanish Inquisition actually was diabolic’.

The outcome, on Lawrence’s part, is a rejection of political violence and what he calls ‘bullying’ that is consistent with his attitudes towards Fascism, Rome and Bolshevism in many other places.

As for the type of control needed over the masses, the Inquisitor, evidently, believes that this must be religious:

Lawrence agrees with his emphasis on the importance of giving people heavenly as well as earthly bread.

One recalls Kangaroo, whose ideal ruler ‘would be a patriarch, or a pope: representing as near as possible the wise, subtle spirit of life. I should try to establish my state of Australia as a kind of Church, with the profound reverence for life, for life’s deepest urges, as the motive power. Dostoevsky suggests this: and I believe it can be done’

Kangaroo’s mention of a ‘Pope’ raises the question of whether, sixthly:

Blavatsky in her 1881 Preface described the story as a “satire” on the Roman Catholic Church especially.

And many critics have seen in the story evidence of Dostoevsky’s anti-Catholic prejudice.

Schmitt, in his 1923 response, whilst acknowledging that the Inquisitor himself was presented as flawed, gave the story as evidence of the ‘anti-Roman temper’ which he associated with liberalism, Marxism, Weber, Freemasonry, Judaism, Bolshevism and the antiChrist.

And whereas ‘The world-view of the modern capitalist is the same as that of the industrial proletarian’, the ‘Roman Church morally encompasses the psychological and sociological nature of man and, unlike industry and technology, is not concerned with the domination and exploitation of matter.

All this has much congruency with Lawrence’s thought.

And indeed by the time Schmitt wrote this Lawrence had picked up on the possibility of political leadership from the Catholic Church.

In a letter of 1921 he wrote:

‘The Catholic church is a deep one. It is trying to form a Catholic world league, political, and taking more the Communistic line. ..It may turn out a big thing. I shouldn’t wonder if before very long they effected a mild sort of revolution here..It would be a clergy-industrial-socialist move..Smart dodge, I think’.

Four months later he wrote from Kandy that England was in danger of being quenched, and that Buddhism and Hinduism offered no answers, but ‘the Roman Catholic Church, as an institution, granted of course some new adjustments to life, might once more be invaluable for saving Europe’.

But there are many critics hostile to the Inquisitor who have criticised the story for its apparent claim to be critiquing specifically Catholicism.

Merezhkovsky, writing in 1901 shortly before the suppression of his own Bogoiskateli, or God-seekers’, group, argued strongly that the Inquisitor’s type of control was as much Orthodox as Catholic.

And Berdyaev noted that the story had been ‘highly acclaimed by K. Pobedonostsev, whom the whole of thinking Russia regarded as the Grand Inquisitor. This misunderstanding was possible only because …it relegated the Legend of the Grand Inquisitor exclusively to Catholicism’.

There is a similar division among critics as to whether the Inquisitor’s type of control, for good or ill, is right-wing.

The Inquisitor makes a clear allusion to the atheist Communism which Dostoevsky, with dazzling prophecy in 1879, saw coming if the people were not given bread, because they would turn against Christ and persecute priests in the name of gaining it.

Lawrence accepts this association, and notes with the benefit of recent hindsight that socialism had not only discarded heavenly bread but ‘even the earthly bread disappeared out of wheat-producing Russia’.

Lenin, therefore, had a double reason to dislike the story.

Insofar as the Inquisitor’s ideas are presented as admirable, the Inquisitor is anti-Communist.

But insofar as he could be interpreted as proleptic critique of Communist rule itself, then he was the Inquisitor.

Rozanov was the earliest to make the connection; in 1879 he called Ivan a socialist, and ‘our socialists … conscious Jesuits’.

Berdyaev explicitly likened the Inquisitor’s rule to not only Orthodoxy but Communism.

Arendt presented the story as being about Robespierre, who like the Inquisitor was attracted to ‘les hommes faibles’ out of pity [not compassion] and simply lust for power.

Indeed in general, during the Cold War the story was often presented in the West as a critique of Communism and endorsement of the freedoms – despite the pains they may entail – of the capitalist West, since after all Dostoevsky was certainly anti-Communist as well as anti-Catholic.

Given this tradition, which ignored Dostoevsky’s anti-capitalism, it is not surprising that Althusser criticised the story as ‘anti-socialist’ in its ‘anticipatory’ depiction of ‘’totalitarian’ socialist society as a society in which every individual will be doubled by his personal ‘monitor’, or Big Brother.

He sees this as a crude anti-socialist ‘myth of the ubiquitous Grand Inquisitor’, effacing exploitation in order to focus on repression alone.

Hesse in 1920, by contrast, thought that all the Karamazovs and Father Zossima were alike in that they rejected ethical rules in favour of what he called ‘a comprehensive ethical laissez-faire.’ Even Ivan, who starts out rationalist, becomes ‘more ardent..more Karamazov-like.’ It is the latter ‘who wrote the poem of the Great Inquisitor’, which is amoral.

And ‘The ideal of the Karamazov, primeval, Asiatic, and occult, is..beginning to consume the European soul.’

Germany had lost WWI because: ‘With the exception of Austria, Germany stood infinitely more willingly and weakly open to the Karamazovs, to Dostoevsky, to Asia, than any other European people.’

This idea has a striking resemblance to Lawrence’s ‘Letter from Germany’ of three years later, with its presentation of the growing, dark Asiatic influence on Germany.

Yet for Hesse it’s possible that ‘these incalculable people may just as well bring about a good as an evil future’. After all Christ himself, and the destruction that he brought to the Ancient civilisations, had come out of Asia.

Lawrence too at various points in the twenties thought that new life might come out of Russia, and, in his different way to Hesse, thought that a positive new direction in political life might come out of this story of Ivan Karamazov’s.

In conclusion, Lawrence’s response to this story, at the end of his life, has elements in common with thinkers of very different political persuasions, but perhaps most of all in common with a Catholic philosopher who would later be Naziism’s leading jurist, and in whose work the War on Terror has created a considerable revival of respectful attention, Carl Schmitt. At the same time he wearily embraced the limited masses with a Christlike care that he had never shown so explicitly before, and with a rejection of violent coercion which he saw as intrinsically inconsistent with the Grand Inquisitor’s vision.