Report of the Twelfth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Terry Gifford

The Plumed Serpent and Ecology

Thursday 17th December 2020

By Zoom (during period of Coronavirus lockdown)

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Catherine Brown, in Kilburn, London

Chloe Rose Campbell, in Stroud Green, London

Andrew Cooper, in Bristol

Jane Costin, in Manchester

Terry Gifford, in Somerset

Malcolm Gray

Bob Hayward, in Melton Mowbray

Ruth Hall

Glenys Hayward, in Melton Mowbray

Pat Hopewell, in Ladbrook Grove, London

Alex Korda, in Ladbrook Grove, London

Jonathan Long, in Suffolk

Dudley Nichols, in Westerham, Kent

Jane Nichols, in Westerham, Kent

Trevor Norris, in Waterloo, London

Dave Orwin, in Bakewell

Iris Orwin, in Bakewell

Anthony Pacitto, in Richmond, London

Mark Prisco, in Hamilton, New Zealand

Sue Reid

Judith Ruderman, in Durham, North Carolina

Stewart Smith, in Dorchester, Dorset

Nahla Torbay, in Wimbledon, London

Kathleen Vella, in Magarr, Malta

James Walker, in Sherwood, Nottingham

INTRODUCTION

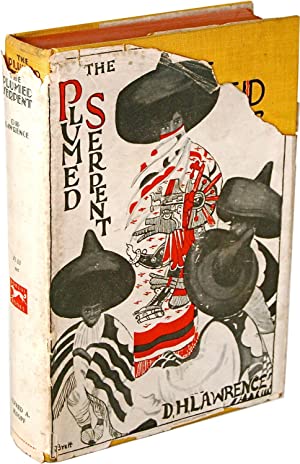

The Plumed Serpent, conceived on Lawrence’s first visit to Mexico in 1923, was published in 1926 (its earlier draft entitled Quetzalcoatl). It has long divided critical opinion.

Terry’s introduction to his ecofeminist approach to the novel is:

‘This was to have been my paper for the Taos conference, where I hope will be able to all meet up next July. Over the last 25 years I’ve been writing conference papers on the role of gender, and women in particular, in Lawrence’s engagements with ecology. Many of these are available on my website and the latest, on metaphor in The Rainbow, which has benefitted from discussion at Nanterre last year, has just been published in the open access online journal Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism. A pattern has emerged of female characters critiquing the ideas of central male characters. Of course, this is not a new observation. Carol Siegal has written that Lawrence ‘assigns the oppositional voice of the tale to female characters’ resulting in Siegal’s observation that the ‘female presence in his fiction deconstructs the discourse of the teller’ (Siegal 1991: 20). I noted that a previous discussion by this group drew attention to the sustained role of Kate in The Plumed Serpent as oppositional. Even on the last pages – even in apparent submission – Kate is ‘mocking’ and challenging. The last words of the novel are hers to her husband: ‘You won’t let me go!’ Whether this is accusation or plea is perhaps, characteristically for Lawrence, ambiguous.’

READING

We were asked to concentrate on Chapter XIII ‘The First Rain’ and Chapter XXVI ‘Kate is a Wife’.

HANDOUT

- ‘I have become conscious of the tree, and its interpenetration into my life. Long ago, the Indians must have been even more acutely conscious of it, when they blazed it to leave their mark on it. I am conscious that it helps to change me, vitally. I am even conscious that shivers of energy cross my living plasm from the tree, and I become a degree more like unto the tree, more bristling and turpentine, in Pan. And the tree gets a certain shade and alertness of my life, within itself.’ (MM 158)

[Terry – I’m indebted to Garry Watson who drew my intention to this passage at the 2017 conference in London, after my paper on trees in Aaron’s Rod. I sent this passage to Wendy Wheeler, an authority on biosemiotics, who has recently died. This is about intuiting the communication through sign systems between species. We now know that trees are a lot more alert and interactive than we’d thought previously, partly from The Secret Life of Trees [‘Hidden’ in some translations]. In my paper on Aaron’s Rod, I’ve developed this whole thing about trees. This is passage is absolutely remarkable. The idea that the tree itself takes an awareness of the human presence. It’s hard to keep up with novels engaging with the sensitivity we find in quote 1. See the painting by Dorothy Brett, ‘L’s Muses’, with Brett at the table, and Lawrence sitting against a tree, revising The Plumed Serpent.]

- ‘We live by the cosmos, as well as in the cosmos. And whoever can come into the closest touch with the cosmos is a bringer of life and a veritable Ruler’ (A 200).

- ‘We must change back to the vision of the living cosmos: we must. The oldest Pan is in us, and he will not be denied.’ (PS 316)

- ‘Animistic becomes the word to describe [Lawrence’s] devotion to the living universe. “This animistic religion,” he wrote to Middleton Murray, ‘is the only live one …’ (William Tindall, H. Lawrence and Susan his Cow, 1939, p. 108)

- ‘Don Ramon argues for a basic, ecological perspective of life, where all minor parts which contribute to the greater system of living should be respected for their own sake as parts of a holistic unit.’ (Anne Odenbring Ehlert, ‘There’s a bad time coming’: Ecological Vision in the Fiction of D. H. Lawrence, University of Uppsala, 2001, p. 139)

- ‘One of the strengths of The Plumed Serpent is its vision of a social order more in tune with ecological values. Like many of the issues dealt with in the novel, however, the environmental vision never reaches a conclusion, but is left hanging in mid-air.’ (Ibid., p. 138)

THE TALK

Insofar as interpretative opinion on The Plumed Serpent divides – and it divides a lot – perhaps the most important dissension is between those who think that the novel substantially endorses the Quetzalcoatl cult, and those who think that the novel more strongly supports Kate’s scepticism towards it.

Terry is in the latter camp, and he combines this with his ecofeminist perspective to argue that Kate – whilst fully alive to the ecological credentials of the movement – is critical of their social application (and therefore performs the task of deconstruction that is performed by many of Lawrence’s heroines towards their male counterparts). By the time of visiting Mexico Lawrence had already explored the dangers of a charismatic movement in Kangaroo. In The Plumed Serpent he applied the same scrutiny to ‘a more ecologically conscious revolution’. The following are Terry’s notes, reproduced here with his permission:

‘New ecocritical theories of the re-enchantment of nature (Patrick Curry), of a more sensitive sense of biosemiology (Wendy Wheeler), of material agency in nature (Jane Bennett) and of ‘radical animism’ (Jemma Deer) invite a new consideration of Lawrence’s vision of a Mexican religion based upon a reconnection with elemental forces and their rhythms. This requires, if it can be achieved, distinguishing what I call ‘ecological animism’ from the regressive primitivism in which it appears to be deeply embedded.

That is to ask whether Ramon’s cry of: ‘We must change back to the vision of the living cosmos: we must. The oldest Pan is in us, and he will not be denied.’ (316) is very different from Lawrence’s perception in ‘Pan in America’ of his relationship with the tree under which he was revising The Plumed Serpent ‘I am even conscious that shivers of energy cross my living plasm from the tree, and I become a degree more like unto the tree, more bristling and turpentine, in Pan. And the tree gets a certain shade and alertness of my life, within itself’ (MM 158). Or whether these are different from this from Apocalypse: ‘We live by the cosmos, as well as in the cosmos. And whoever can come into the closest touch with the cosmos is a bringer of life and a veritable Ruler’ (A 200). If one can recognise and suspend all the problems associated with a ‘Ruler’, rituals for coming ‘into the closest touch’, becoming ‘more like unto a tree’ and that sensibility which ‘will not be denied’, is it possible to distinguish a viable ‘ecological animism’ that Lawrence derived from this ‘spirit of place’? In the place of this novel, Mexico, the elements appear to dominate all organic life – water and earth, rains and volcanoes, sun and shadow – just as colonialism (and its Catholicism) dominates cultural life. Is it possible to argue that the novel’s social alternative to colonialism comes to cloud the idea of personal spiritual re-engagement with regional elementals? That the social application of ideals founders again in Lawrence’s work?

Of all Lawrence’s novels perhaps The Plumed Serpent has fared most badly, even, or especially, amongst Lawrence’s admirers. In the most careful and considered discussion of the novel to date, Neil Roberts not only identifies the different strains of racism in the novel, but demonstrates ‘manipulative episodes … that are self-evidently indefensible’ (165). But isn’t that the point? Isn’t this another novel in which ideals become abstracted into flawed expressions in their social application?

In 1970 I spent a week discussing Women in Love at a summer school run by Keith Sagar. Our discussions were very much influenced by the newly published River of Dissolution by Colin Clarke (1969). I came away admiring Birkin’s calls for the dissolution of corrupt social practices and his ideals of more balanced personal relationships between men and women expressed in notions like ‘star polarity’. I visited Keith two months before he died and told him I was working on Women in Love again. He offered me the idea that in Birkin Lawrence posited all his best ideas up to that point (and his strongest anxieties) to be critiqued by Ursula and the reader. This concurred with the observations I had been making about the role of women as deconstructionists of male characters’ abstract ideal pontifications. Lawrence came to New Mexico having exposed the dangers of socially organised and charismatically led ‘mateship’ in Kangaroo. Is it possible to argue that in The Plumed Serpent he exposed the flaws in a more ecologically driven religious revolution precisely by including, in Neil’s words, ‘manipulative episodes … that are self-evidently indefensible’?

The novel begins by exposing a twentieth century culture that tolerates the bullfight, the ritual killing of animals. It ends by exposing a supposedly reformed culture that tolerates the ritual execution of four men and a woman. Surely there can be no mistaking Lawrence’s intention here? After the executions Kate feels revulsion from the male exertion of ‘pure, awful will’. But she is ‘spell-bound’ by its pure force. Yet that too is qualified: ‘She was spell-bound, but not utterly acquiescent. In one corner of her soul was revulsion and a touch of nausea’ (PS 387). So let’s park this obvious critique of the outcome of a male-dominated religion and return to its original impulses.

Before the chapter ‘The First Rain’ there are two striking moments when Lawrence prepares the reader for the ecological animism that is evoked in that chapter. The first is from Don Ramon, p. 80.

- Rooted in Mexican soil, local earth, ‘spirit of place’, 2. material, known, worked with 3. Symbolic network of ecology: Tree of Life.

The second is from Kate, disembarking from the lake, p. 108.

- Patronising, The breath of life in Mexican people 2. Feels it herself, surprised by her language 3. Potency, flux, material earth, air, sun, beating heart of the earth.

In ‘The First Rain’ chapter these elements are brought alive in mythical terms and ritualised. If Anne Odenbring Ehlert’s statement (5) is right that ecological perspective begins in this chapter.

- 196a: ‘Serpent of the earth, snake of the fire at the heart of the world’ is to be felt in the human body. Corporeal apprehension of ecological connection. From animal awareness to a sense of the shared animism with the earth.

Elemental materiality that is re-enchanted: snake, earth, fire, rocks, trees.

- 196b: Growing maize and mining minerals, economic life is dependent upon the living earth.

- 197: Rain about to bring growth of maize and men. (At this stage, of manhood and womanhood, both.)

- 198: Bird serpent (The Winged Serpent?) – thunder, lightning, Bird of the Beyond, blue heaven, sun, Morning Star.

- 199: Animism shared.

- 200: ‘Earth! Earth! You are alive as the globes of my body are alive. Breath the kiss of the inner earth upon me, even as I sit upon you.’

- 203: Cipriano points out that this is what Kate has been missing: ‘It is good to be awake.’ ‘Perhaps,’ she said.

- 243: Kate apprehends the cosmos.

- 264: Ramon agues with the bishop that ‘without a religion that will connect them to the universe, they will all perish. Only religion will serve: not socialism, nor education, nor anything.’ William Tindall (Handout 4).

So in the ‘Kate is a Wife’ chapter Lawrence describes both the personal and the social implications of this religion for Kate on the one hand and for the country on the other. Here is the old fear of loss of individuality, most commonly a male fear in Women in Love, Aaron’s Rod and Kangaroo.

- 414: Kate’s sense of Mexico’s old, non-cerebral, animal mode of consciousness is imagined in material terms of pre-glacial landscapes.

The word ‘fusion’ is used 3 times.

- 421: Kate apprehends the cosmos again, but in more personal terms to become translated into sexual experience of ‘volcanic deeps’, beyond self-satisfaction.

- 422: ‘her strange, seething feminine will and desire subsided in her’.

- 424: Cipriano and his horse are said to have ‘belonged to one birth’ and then Kate experiences reconciliation with the snake, feeling a connection to ‘all the unseen things in the hidden places of the earth’.

Is Ehlert right that the environmental vision is ‘left hanging in mid-air’?’

Terry concluded that Lawrence is, as ever, skeptical about the leadership of social reform movements – and that he recognises the conundrum with problem to ecological improvement that follows.

WORKS CITED

Bennett, Jane, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

Curry, Patrick, Enchantment: Wonder in Modern Life (np: Floris Books, 2019).

Ehlert, Anne Odenbring, ‘There’s a bad time coming’: Ecological Vision in the Fiction of D. H. Lawrence(Uppsala: Uppsala University Library, 2001).

Roberts, Neil, D. H. Lawrence, Travel and Cultural Difference (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Siegel, Carol, Lawrence Among the Women (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1991).

Tindall, William, D. H. Lawrence and Susan his Cow (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939).

Wheeler, Wendy, Expecting the Earth: Life, Culture, Biosemiotics (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2016).

THE DISCUSSION

There was some concurrence with Terry’s perspective that the novel sides with Kate’s critique of the Quetzalcoatl movement – for example from Judith, Jonathan, Jane and Andrew. Andrew observed that readers of Lawrence’s works often look out for who Lawrence’s mouthpiece is; here, he said, it is clearly Kate. Jonathan thought that: ‘The Plumed Serpent is definitely a difficult novel, but if you see him as an experimental writer, I think it becomes a little clearer. He is portraying a culture that he clearly does not approve of. The novel has been misinterpreted by people like Kate Millett, with short quotes or misquoting. He certainly doesn’t approve of the violence in the novel.’ He supported this by saying that the cult’s practices were inconsistent with what Lawrence wrote at other times, and also elsewhere at the same time; like Kangaroo, the novel explores a new, superficially-attractive political movement and finds it wanting. Jane thought that the ritual depicted in Chapter XIII was clearly an instance of Ramon trying to convince himself of the reality of the serpent in which he wanted to believe, and that ‘eco-Irish’ Kate ‘constantly undercuts’ the men around her. She was also interested in the frequent nakedness of the cultists, and the importance of the body’s connection with the cosmos. Terry concurred that this related to blood consciousness, and that Lawrence believed that plants had blood consciousness – ie vital connection with the dynamics of nature; this was the aspect of the Quetzalcoatl cult which Lawrence found attractive.

Stewart complicated that picture by adding that: ‘the discussion so far has assumed that reconnection with elemental forces – specifically Mexican forces – is a positive thing. Yet throughout the novel Mexico is repeatedly described in ambivalent or negative terms: “the spirit of place was cruel, down-dragging, destructive”; America is the “great death continent”, the continent of “undoing, dissolution”, of revenge and “victim and victimizer”. Even Ramon, in the chapter Terry pointed us towards, describes Nature as vindictive – “He [the earth] sends sorrow into our feet, and depression into our loins” for failing to respect the “alive earth”. Perhaps Kate’s ambivalent response to Cipriano’s call to her to be “awake” is related to these cruel, destructive, elemental forces that pervade Mexico and its people– as she’s afraid of the horror and terror of Mexico?’ Terry agreed: ‘yes, it can kill us. The death process is not ignored in Lawrence. The ambivalence Kate feels is not just Western culture shock, it is recognising a death process.’

Andrew took a middle line: ‘there’s an inconclusive feel about the narration. It’s neither for nor against the religion it describes’. But Bob found it hard to believe that Lawrence would describe at such great length something of which he disapproved: ‘I feel that Lawrence is exploring the idea of creating or evoking a religion that is completely moved away from the Western religions, mainly Christianity.’ Accordingly he thought that the rhetoric of the passages in which Kate stands up to Cipriano and Ramon on balance favour the latter, and suggest that Kate is making a mistake: ‘She’s always implicitly worsted when she gets into an argument with Cipriano’. Kate, moreover, is condemned for her racism towards Cipriano when she first sees him. Nor does Kate’s opposition have any effect on the men’s activities: ‘they are never diverted by her. She is merely questioning them with [what Lawrence presents as] her Western prejudices’. It was, he argued, important to note that Ramon is not interested in political leadership; it is the President Montes who imposes the cult on the country. Nor, even then, is it a dictatorship; people are not forced to follow Quetzalcoatl.

Alex agreed that the novel favours the religion, and therefore found it to be either ‘a Philip Pullman fantasy not related to Mexican or German reality’ or ‘a really awful novel’, in a historical context which included the Munich beer hall putsch having taken place two years earlier. He also, ‘as a chemist’, found the idea of physiological interchange between beings such as man and tree to be ‘nonsense’.

With regard to history (as a matter of fact) there was no Aztec revivalism; Lawrence has invented the cult; but the socialist revolutionary government certainly suppressed the Catholic Church. There was a period when the watch-less mass of the people lost track of time, because the churches, together with their clock towers, had been destroyed.

Bob pointed out that Mexican writers were inspired by the novel: ‘They realised they didn’t have to have a Western approach to describing what was happening in it’; its first translation into Spanish was done in 1940s in Buenes Aires. He has subsequently adumbrated: ‘As for Lawrence’s attitude to Mexico, Brett relates how, on a long train journey to Southern Mexico, Lawrence tried to tip a guard who replied: “No, not from you: you’re one of us”. A leading Mexican newspaper reported the ‘great English writer’s visit’ to Mexico and commented: ‘He understands us.’ In this novel, he had got Mexico right, according to their educated readers.’ Judith recalls being in Mexico City in 1979/80 and finding the novel listed on a reading list in her hotel room…

When the discussion turned to a consideration of how the novel spoke to today’s problems, it was recognized that there is still a tension between decisive ecological policies and the democratic will. Malcolm identified a problem in the fact that a truly ecological leader is ‘more likely to be female than male, due to female awareness of life, but Lawrence doesn’t want a female leader.’ Terry agreed: ‘I’ve said the females in the novels are critiquing the male carriers of ideas. But I can’t think of Lawrence considering a female leader in any of the novels.’ Bob found this unsurprising, since there were then no examples of women presidents or prime ministers at the time. Trevor said that Lawrence was making an ecological argument on the foundation of ‘eco-consciousness’ rather than that of the political plain, which Lawrence found to be that of the ‘ego’.

Madrid 1980 edition of a Spanish translation of the novel, published just 5 years after Franco’s death permitted a relaxation of censorship and the publication of many of Lawrence’s works, which had hitherto been banned.