Report of the Tenth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Adam Lang

Sea and Sardinia and the Spirit of Place

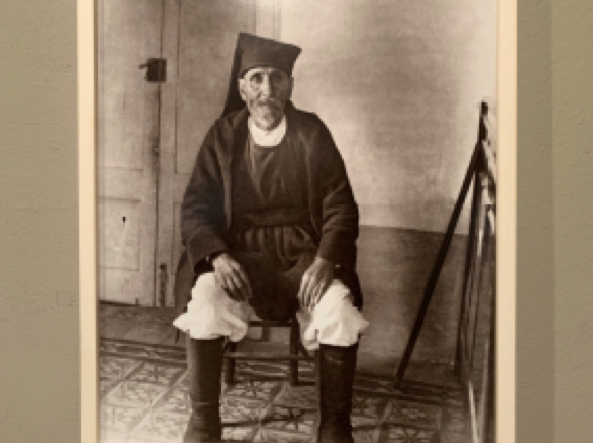

Photo by Max Leopold Wagner (1880-1962), a scholar of romance linguistics who travelled frequently in Sardinia 1905-27; Lawrence was there in 1921. Lawrence, said Adam, ‘almost describes that man’.

Friday 30th October 2020

By Zoom (during period of Coronavirus lockdown)

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Michael Bell, in Leicester

Shirley Bricout, in France

Catherine Brown, in Kilburn, London

Chloe Rose Campbell, in Stroud Green, London

Nicolas Ceramella, in Milan, Italy

Jane Costin, in Manchester

Isobel Dixon

Paul Filmer, Muswell Hill, London

Gareth Giddings, in Portishead, Nottingham

Kate Foster

Mary Foster

Bob Hayward, in Melton Mowbray

Glenys Hayward, in Melton Mowbray

Pat Hopewell, in Ladbrook Grove, London

Lee Jenkins, in Cork, Ireland

Alex Korda, in Ladbrook Grove, London

Adam Lang, in Shepherds Bush, London

Jonathan Long, in Suffolk

Daniele Marzeddu, in Bologna, Italy

Stefania Michelucci, in Italy

Dudley Nichols, in Westerham, Kent

Jane Nichols, in Westerham, Kent

Trevor Norris, in Waterloo, London

Dave Orwin, in Bakewell

Iris Orwin, in Bakewell

Anthony Pacitto, in Richmond, London

Janet Perry, Leicester

Lara Taylor, East Coker, Somerset

Nahla Torbay, in Wimbledon, London

Kathleen Vella, in Magarr, Malta

John Worthen, Germany

Colin Yeates, in Muswell Hill, London

NB This was the group’s second meeting with people in live attendance from outside the UK: Lee in Ireland, John in Germany, Shirley in France, Nick and Stefania in Italy, and Kathleen in Malta.

EPIGRAPH

‘Comes over one an absolute necessity to move. And what is more, to move in some particular direction. A double necessity then: to get on the move, and to know whither.

Why can’t one sit still? Here in Sicily it is so pleasant: the sunny Ionian sea, the changing jewel of Calabria, like a fire-opal moved in the light; Italy and the panorama of Christmas clouds, night with the dog-star laying a long, luminous gleam across the sea, as if baying at us, Orion marching above; how the dog-star Sirius looks at one, looks at one! he is the hound of heaven, green, glamorous and fierce!—and then oh regal evening star, hung westward flaring over the jagged dark precipices of tall Sicily: then Etna, that wicked witch, resting her thick white snow under heaven, and slowly, slowly rolling her orange-coloured smoke.’

From the opening to Sea and Sardinia

INTRODUCTION

Sea and Sardinia is a creative non-fiction account of a trip taken by Lawrence and his wife Frieda from Sicily to Sardinia for just over a week in January 1921. It was written on Lawrence’s return to Sicily. Adam Peter Lang is a former London secondary school teacher and school leader, now an education consultant writing a PhD at UCL on the implementation of the Prevent Policy in secondary schools. He is also a freelance travel writer and member of the Globetrotters Society with a particular love for Sardinia, which he has regularly visited over the last two decades. He is in contact with those who run an annual D.H. Lawrence Festival there, and who are currently planning the 2021 Festival which will celebrate the centenary of Sea and Sardinia. It is hoped – but not yet certain – that this event will be able to happen in person.

THE TALK

Adam started as he continued, by linking Lawrence’s past to our present – particularly the context of the Covid pandemic (also discussed in the May meeting of this group https://catherinebrown.org/may-2020/). At various moments in his life Lawrence could not travel, for health or geopolitical reasons; likewise we cannot travel now, and are therefore developing a different relationship to travel writing. For example, Adam has been regularly cycling around his area of London (he lives in Shepherd’s Bush) observing how public life has changed during the time since the first 2020 lockdown was imposed in March. This raised the question of the definition of travel writing: is it a description of a place that is not home to the writer? or of the process of travelling? or is it writing about a place addressed to those who do not know that place? Is just one of these criteria enough to make it travel writing? Adam observed that the pandemic had produced London tourism – and therefore also travel writing – amongst Londoners.

He presented Lawrence as having innovated in travel writing in numerous ways, from his explicit concern with economising whilst travelling (‘he prices everything’) to his explicit concern with the ‘spirit of place’, a concept which recurred throughout the talk. He therefore influenced numerous travel writers since him, for example Paul Theroux (Deep South) and Bruce Chatwin (In Patagonia).

He thought that Lawrence’s works helped us to challenge certain political pieties, including that of neoliberalism, and noted that this is also critiqued by a recent book by Pankaj Mishra, Age of Anger. He explained how on Sardinia recently several far-right-wing groups have emerged and taken power: the Sardinian Action Party and the Brothers of Italy. There is anti-migrant graffiti to be found in Sardinia now (as well as other graffiti that is pro-migrant). Here too, then, is an echo of the time that Lawrence lived in Italy, during its first fascist decade. These groups are supportive of Lawrence and of the Lawrence festivals which are held there.

He shared with us that:

‘Today the Sardinians come across as an attractive and interesting people, very simpatico, who hold onto their island customs and lifestyle. Unlike the more exuberant mainland Italians the Sards have a quiet reserve, friendly but not outgoing.

“There is no place in Italy that is less Italian” write Dana Fararos and Michael Paul’s in their recent Cadogan guide. It is well worth visiting hidden Sardinia today with its turquoise, transparent seas and (outside of mid-summer) uncrowded beaches, spectacular wild landscapes covered with olive trees and vineyards and dotted with hundreds of mysterious Bronze Age towers, lagoons full of pink flamingoes, herds of wild horses, shepherds, peasant life, superb food and distinctive wines, brilliant coloured rugs spun on ancient looms and almost a festival for every day of the year.

Yet for all of its beauty Sardinia has an earthy grit and many, especially the young, leave to find employment and opportunities further afield. Today unemployment is almost double that of the mainland. Aside from tourism Sardinia is perhaps a land that globalisation has left behind. In Mandas, a small town in the centre of the island, where DHL and the QB stayed overnight in the harsh winter of 1921 in “the stone cold station hotel” and ate “a bowl of smoking cabbage soup”, today if you search carefully you can find a couple of dusty plaques commemorating their trip, and each early summer the locals hold a DH Lawrence festival – an eclectic mix of folk culture, local arts and crafts, literature, music, food, wine and dance. In Cagliari you can take a gentle paced stroll as they did and at the harbour front on Via Roma find a table “on the pavement among the crowd” and slowly sip a drink whilst watching the evening passeggiata; it looks almost the same as in 1921.’

THE DISCUSSION

Jane Nichols shared her first edition of Sea and Sardinia via her Zoom screen: Edward Garnett had signed it, and it contains David Garnett’s bookplate. She bought it from a bookseller who was selling David’s book collection after his death in the 1960s. Dudley noted that the book had first appeared as two chapters in Dial Magazine. It was then published in its entirety by Thomas Seltzer in the USA in 1921 and by Martin Secker in England in 1923. Jonathan Long added that Nicholas Joost has written a book on DH Lawrence and the Dial, which explains that The Dial was an American periodical focusing on modernists in the 1920s, and that Lawrence’s prose and poetry appeared there regularly from 1920-29. This included what was per-word probably some of his best-paid work. For Sea and Sardiniahe collaborated with Jan Juta, who produced eight pictures in colour. Unusually for him, Secker also included these illustrations in the first English edition. Jonathan thought the particular care taken by many parties over this book had been apt, since it is one of Lawrence’s most accessible and best books. Jane added that Juta was initially planning to go to Sardinia with Lawrence, but eventually went later, and without having read the book. Most of the illustrations are therefore not directly related to the writing, but have a flat, vibrant colour, which is apt; they are mostly of costume, partly of the countryside. Lawrence showed great trust in the young painter whom he and Frieda had met in Rome, and Juta he is mentioned in the final chapter, ‘Back’, as one of the painters who greets them in Rome. Isobel Dixon and Nick Ceramella (who organized the 2013 Lawrence Conference in Gargnano) both stressed that this was a production that needed to sell well – he wrote it for the money – and which did so.

Adam noted that there is still some use of traditional dress in Sardinia

Dudley Nichols said that he was struck by the humour of the book, and by the respects in which it resembled a novel. Adam responded that when Sardinians state – as they often do – that Lawrence is being critical of them, he points out that Lawrence’s humour in the book is in fact affectionate and gentle.

Jane Costin pointed out that in his descriptions of the town of Mandas Lawrence is reflecting on his experience of Cornwall: in the granite he sees the connection between the two places, before realizing the limited extent of the connection. She recommended a book about moving to Cornwall, Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place by Philip Marsden (2014), which also describes, and sees significance in, Cornwall’s granite. She observed that sometimes one thinks and writes better about one’s home place precisely when one is away from it – a kind of inverted travel writing – but that that is, for most of us, at present not possible due to the lockdown. Daniele Marzeddu, a Sardinian based in the UK, said that he too compares the two islands (or Sardinia and Britain). Nahla Torbay responded that, as a British Syrian who has been living in England for 25 years, she sympathises with Lawrence’s position of never having left the spirit of his home behind, despite rarely being there. Dudley noted that the visit to Sardinia was in part in order to see if they wanted to actually move there; they decided not to, and on their return took out another year’s lease on the Fontana Vecchia at Taormina. Lee Jenkins noted that Lawrence talks about Taormina as well as Sardinia as having the same spirit of place that he found or imagined in Cornwall. With regard to imagining, Paul Filmer noted that in her eulogy of Lawrence Rebecca West said that he was only ever writing about the state of his own soul, but that being in a new place stimulated him to greater exploration of his interior.

This led to a discussion of negative reactions to place, which might at least in part be an expression of something internal. Catherine asked whether anyone could think of moments in Lawrence’s writings when an ‘anti-epiphany’ (the reverse of a moment of transcendent revelation and joy) is experienced, as Mrs Moore does in A Passage to India at the Marabar Caves. Trevor Norris mentioned a moment in Kangaroo when it is stated that ‘into every living soul wells up the darkness, the unutterable. And then there is travail of the visible with the invisible. Man is in travail with his own soul, while ever his soul lives. Into his unconscious surges a new flood of the God-darkness, the living unutterable. And this unutterable is like a germ, a foetus with which he must travail, bringing it at last into utterance, into action, into being […] The dark God, the forever unrevealed. The God who is many gods to many men: all things to all men. The source of passions and strange motives.’ He also (in conversation afterwards) noted that there was a scene where the foreshore has been made unrecognisable by the force of the sea and the wind after the storm: ‘The sea was enormous: wave after wave in immediate succession, raving yellow and crashing dull into the land. The yeast-spume was piled in hills against the cliffs, among the big rocks, and in swung the raving yellow water, in great dull bows under the land, hoarsely surging out of the dim yellow blank of the sea […] the whole shore was ruined, changed: a whole mass of new rocks, a chaos of heaped boulders, a gurgle of rushing clayey water, and heaps of collapsed earth.’ Also: ‘Then comes a hollow, desolate bare place with empty greyness and a few dead, charred, gum-trees, where there has been a bush-fire.’

Jane Costin cited a moment in Mexico when Lawrence refused to get out of a train – despite being berated by those accompanying him – because a massacre had taken place there. Paul Filmer thought that Lawrence’s experience of Malta with Maurice Magnus constituted a wholly destitute vision of society. John Worthen said that there were several moments in New Mexico when Lawrence was responding to the ‘most mysterious.. crude half-created spirit of place…the gods of those inner mountains’; one sees this in St Mawr. Anthony Pacitto noted that in The Lost Girl: ‘it seems that there are places which resist us, which have the power to overthrow our potent being’, which ‘refuse our living culture, and Alvina had struck on one of these on the edge of the Abruzzi’ (from Chapter 15, Caliphano).

We finished the session by looking to the future. It is hoped that in July or September 2021 a festival to celebrate the centenary of Sea and Sardinia will take place in Sardinia; the idea would be to spend a few days tracing the route. Adam Lang and Daniele Marzeddu would like the DH Lawrence Society to be involved in this. Daniele has his own film projects concerning Lawrencian locations in Sardinia and Sicily (seaandsardinia.org

Https://vimeo.com/397029374). If travel is not possible by summer 2021, then film will have to do by way of geographical bridge; but let us hope.