The following article was published in the June 2017 issue of Standpoint magazine, and it may be read here.

My Anglo-Greek marriage has often caused me to reflect on the relations of our two countries. Their similarities are less obvious than their differences – but a moment’s reflection will summon a few. Britain and Greece are former centres of maritime empires lying at opposite corners of Europe. They strongly identify with their past glories, towards which their tourist industries are decisively orientated. Their cultures are particularly rich in literature. Each looks to a great power with which it has historically good relations: the United States and Russia. Late amongst Western countries to join the European Union, now they are early amongst them to be thinking of leaving it – thus sharing the ‘exit’ suffix that has come into common use.

Yet even to mention these similarities is to summon the differences by which they must be qualified. These all point to the power differential which has pertained at least since Western Europe’s ‘early modern’ period began, and which has over the last two centuries expressed itself in the actual domination of Greece by the United Kingdom. The latter period was symbolically opened in 1801 by the British Ambassador to Istanbul, Thomas Bruce, who – it is claimed – grossly exceeded the remit of his firman from the Sultan to make drawings and casts of the Acropolis sculptures. Controversy over the seventh Earl of Elgin’s acquisition of a third of these sculptures started almost immediately. A British Museum select committee questioned him closely as to the legality of their removal, when he tried to sell them to the Museum in 1816. The Hellenophile Byron, Keats, Shelley, and Thomas Hardy, all supported their return to Greece well before my husband’s aunt, Melina Mercouri, upped the ante on becoming Greek Minister of Culture in 1981. Byron complained thus:

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

But whatever the contents of the (lost) firman, and the rights or wrongs of the case, Britain simply had – and has – the greater power.

The marbles are not all that it has taken. At the Congress of Vienna, Britain took the Ionian Islands from France, who had taken them from Venice. Lawrence Durrell described the traces of English culture still palpable in the Corfu of the 1930s (the islands had been returned to Greece in 1864) as follows:

The discreet picnics among the olive-groves, the memoranda, the protocols, the bustles, sidewhiskers, long top-boots, tea-cosies, mittens, rock-cakes, chutney, bolus, dignity, incompetence, book-keeping, virtue, church bazaars; you will find traces of all of them if you look deeply enough. The flash of red hunting coat through the olive-groves as the officers galloped over the island on their dangerous paper-chases; the declarations of love among the cypresses, the red-faced sportsmen setting out for Albania. Big Tom, Adams, Leech, and ‘Fusty’ Andrews; Lockler, Jones, and Jervis White-Jervis. Dr. Anstead fussily visiting these ‘embayed seas’ to record the lamentable venality of the islanders. Edward Lear’s gloomy pictures of Perama and the Hyallic Gulf.

The deposition in 1862 of the Russophile King Otto Wittelsbach, and his replacement by the Anglophile George Glücksberg, were managed under British influence. In the following decade Britain took de facto control of Cyprus, which it retained for nearly a century, formalised after the First World War, and maintains in attentuated form through its extant military bases on the island. The abdication of King Constantine in 1917 (when he leant towards Germany), and his reinstatement in 1920 (when he was willing to invade Soviet-inclined Turkey and the Soviet Union itself), were both managed under British influence. In the Second World War, the British first helped the Greeks to eject the Italians and Germans, then helped the monarchists to win the subsequent Civil War. Accordingly, Britain, like the United States, supported the Colonels’ military dictatorship of 1967 to ’74.

This history of dominant relations with Greece is apparent, in one way or another, in the variety of Anglo-Greeks of which I am aware. My husband’s grandfather, Theodore Stephanides, grew up as an English-speaker in India because his father had married into the Anglo-Greek Ralli family. He therefore had a Raj childhood in common with the Durrell children whom he was to befriend in the 1930s. His wife, née Mary Alexander, was the daughter of a former British diplomat in Corfu and a Corfiot aristocrat. Lawrence Durrell spent his career in those parts of the British Empire which mapped onto those of ancient Greece: Corfu, Alexandria, Cyprus. The Duke of Edinburgh is a scion of the Greek Glücksbergs, who married back into Queen Victoria’s family. London was the obvious place of refuge for the last King, Constantine II – as it was for my husband and his parents – when all of them variously fled the military dictatorship.

Yet – just as the Romans felt ambivalently towards the Greeks, so too have the British. This fitted with the Victorian self-identification with the Romans. The Greeks may, to the Romans and British, have been the dominated people – but they possessed something which the dominators knew that they lacked. For centuries the British education system was deferentially orientated towards ancient Greek culture. Just as the Romans were conscious of accepting Greek gods into their pantheon, so – later – both they and the British were conscious of the shaping influence of Greek philosophy in their state religion of Christianity.

Certain Victorians came to see the English education system’s veneration of the ancient Greeks as excessive. George Eliot exemplified such modernising, cosmopolitan impatience. But her male counterpart, Matthew Arnold, identified the ‘Hellenic’ with precisely that cosmopolitan openness of inquiry, fineness of culture, and lightness of spirit, which he diagnosed to be lacking amongst the anti-intellectual, xenophobic, ‘Philistine’ English. The Greeks today continue to represent the spirit of internationalist culture – at least in their administration (currently under my father-in-law’s presidency) of the Cultural Capitals of Europe scheme.

British veneration of the Greeks overlooked entirely the millennium of Byzantine history, which was degraded into a mere negative adjective for complexity. Early nineteenth century philhellenism, despite being anti-Turk, was less interested in promoting Christianity than it was in reviving Greece’s ancient past. The attitude of many patriotic Greeks of the present, such as my anti-clerical father-in-law, is similar.

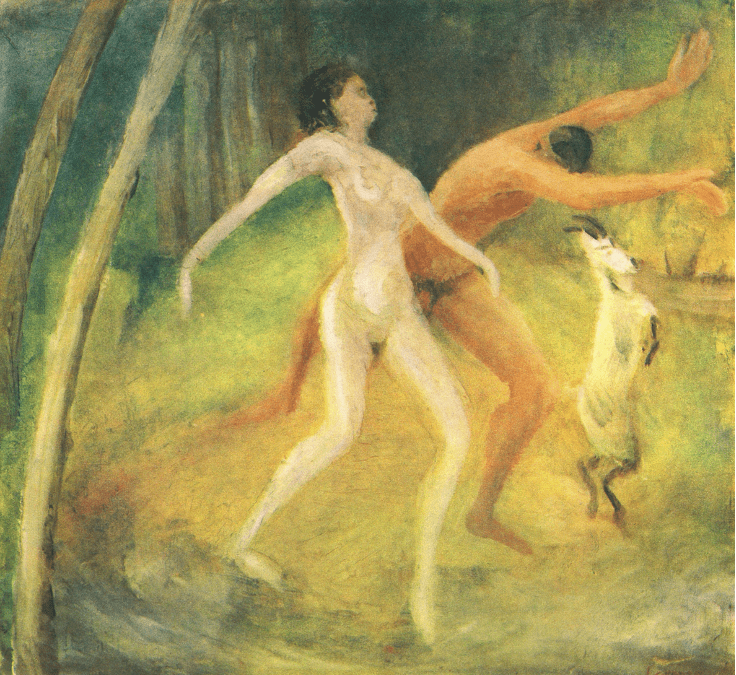

But the philhellenes also put their own, distinctively North European, imprint on the British understanding of Greece. Since their time, Greece has connoted qualities quite other than those which Englightenment neoclassicism had associated with ancient Greece. The Romantics, in short, made Greece Romantic – and such it has remained. Thus it took its place alongside Italy as one of those places in Southern Europe which liberated pale Northerners into the experience of suntan, sex, and Life itself.

Gerald Durrell’s 1956, ‘69 and ‘78 memoirs of Corfu in the 1930s are clearly the recollections of a pre-pubescent, and sexual matters are downplayed even to the dramatic extent of excising all mention of Lawrence’s wife Nancy, Theodore’s wife Mary, and Theodore’s daughter Alexia, whom Theodore hoped that Gerald would marry. Nonetheless, they describe the ascent of an English person into a heightened sensuous existence, deeply attuned to the glorious sun, fauna, flora and food. The British lack of such things is summed up in the famous opening of My Family and Other Animals, in which Larry suddenly expostulates to his family – variously indisposed as the result of foul August weather – that life in England is impossible, and that they must all move to Corfu forthwith. ‘“Why do we stand this bloody climate? What we all need is sunshine…a country where we can grow.” […] So we sold the house and fled from the gloom of the English summer, like a flock of migrating swallows.’

As Michael Haag’s illuminating new biography of the Durrells makes clear (The Durrells, 2017: Profile), this was not at all how the decision was made. But his book also stresses how unhappy the Durrell boys were in their various stints at English boarding schools, and what a liberation back into the unregimented days of their Indian childhood the move to Corfu was. The very beauty of Gerald’s prose recreates the paradise in the reader’s mind: ‘The sky looked as black and soft as a mole-skin covered with a delicate dew of stars. The magnolia tree loomed cast over the house, its branches full of white blooms, like a hundred miniature reflections of the moon, and their thick, sweet scent hung over the veranda languorously, the scent that was an enchantment luring you out into the mysterious, moonlit countryside’. Meanwhile Lawrence’s 1945 Corfu memoir, Prospero’s Cell, reveals a world of naked bathing which is the response of a mature sexual being – and one who had passed through London’s Bohemia at that – to Corfu’s nature.

But they were not the only contributors to a post-war intensificiation of the British association of Greece with hedonism, liberation, and general (to use D.H. Lawrence’s word) unEnglishing. Willy Russell’s 1986 monologue play, and 1989 film, Shirley Valentine, liberated a middle-aged English housewife into renewed sexuality and self-confidence (somewhat as the 2016 and 2017 ITV television series The Durrells have unhistorically liberated the widow Louisa Durrell). When Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1946 novel Zorba the Greek, translated into English in 1953, became a smash-hit film in 1964, the mainland Greek protagonist was significantly turned into an Anglo-Greek. Basil’s intellectual detachment is broken down by his connection to the vital Zorba, who taught him how to love santuri, sirtaki, and taking days as they come. Four years earlier, Never on Sunday, starring my husband’s aunt Melina Mercouri, used a similar plot – except that the pale Northerner was an American called ‘Homer’, who gave up on trying to restore the Piraeus prostitute Ilya to ancient Greek glory after recognising the lack of vitality in himself. He ends the film by drowning his notebooks, shedding his Classicist scholarship and scholarly attitudes together.

In the following decade came Peter Shafer’s 1973 play Equus, in which the hellenophile psychiatrist Dr. Dysart ends the play by doubting his own profession of making people sane, and wanting instead to become fully alive. He tells his colleague Hesther, with reference to his wife:

I tell everyone Margaret’s the puritan, I’m the pagan. Some pagan! Such wild returns I make to the womb of civilization. Three weeks a year in the Peloponnese, every bed booked in advance, every meal paid for by vouchers, cautious jaunts in hired Fiats […] Such a fantastic surrender to the primitive. […] I sit looking at pages of centaurs trampling the soil of Argos – and outside my window he [his patient Strang] is trying to become one, in a Hampshire field! […] Then in the morning, I put away my books on the culture shelf, close up the kodachrome snaps of Mount Olympus, touch my reproduction statue of Dionysus for luck – and go off to hospital to treat him for insanity. Do you see?

Such attitudes as those embodied in these works may well have been therapeutic for North Europeans deficient in vitamin D and spontaneity. And they recovered a real aspect of ancient Greece – the Dionysian – which neoclassicism, Arnold’s Hellenism, and the bleached architecture and sculpture that we have inherited and find hard to unimagine – have all denied.

But this attitude significantly mistakes modern Greek culture, shaped as it has been by centuries of Orthodox and orthodox Christianity. The Durrells’ memoirs and their recent adaptations downplay the disapproval aroused by the Durrells’ Bohemianism amongst not only the Anglo-Corfiot high society to which Theodore Stephanides belonged, but the Corfiot peasantry, who deeply objected to Lawrence, Nancy and friends bathing naked; according to Haag, ‘They were known to have been stoned by the village priest and boys’. Neither Lawrence nor Gerald mention the fact that Leslie made one of their maids, Maria Condos, pregnant (as my mother-in-law recently told me). When the maid’s brothers threatened to kill her for her disgracing them, she fled to England to work for the Durrells there. Around the same time, according to Kazantzakis’s imagination, a Cretan widow was stoned and beheaded alive for a one-night stand with an Englishman. Theodore’s writings such as Island Trails (1973), and the posthumous Autumn Gleanings (2011), contain several anecdotes of this kind of patriarchy.

The clash between the British vision of Greece and the reality came to a head during the dictatorship, when British tourists continued to flood into Greece in their miniskirts, with their beards, and holding hands – to find all of these things illegal in the ‘Greece of the Christian Greeks’. On finding the tourist income to collapse, the Colonels quickly unbanned these things for foreigners. Nonetheless, my husband’s recollection of arriving as a small boy in the London of 1968 was that it was like moving from a black and white film into technicolour – the reverse of the trope of grey England and colourful Greece. History since then has produced further instances of this clash – as on Mykonos, where the film of Shirley Valentine was shot, which later became the Cycladic capital of British hedonism. Lawrence, Gerald and Theodore were all appalled by the Anglicised Corfu of their several post-war visits, which they had themselves helped to create.

Thus it was that, visiting Greece for the first time with my future husband, I started on a steep learning curve. He explained: Northern women were seen, especially by the older generations, as barbaras: strong, attractive, liable to be drunk, sloppily dressed, and sexually available. Like their male counterparts, they liked to do eccentric things such as turning brown, lying on sand, walking round ruins, or flogging round an island in search of its fauna. All this explained much: why I was looked at askance when I poured myself a second glass of wine at table; why I was the only person I saw jogging in the royal palace’s gardens; why my future father-in-law, on seeing how I was dressed for dinner, turned to his son and commanded ‘buy her some shoes’; why Mount Hymettus (supposed location of the forest in Midsummer Night’s Dream) turned out on closer inspection to lack the infrastructure for walking to which the Peak District had accustomed me.

But these cultural differences are not the sole source of British misapprehension of Greece. It is, of course, in the nature of most tourism to focus on a country’s timeless aspects – its safely-past history, or its nature – rather than its political near-past and present. This is especially the case if the latter are painful, and/or the climate is pleasant; one visits Berlin, for example, in a different kind of tourist mode. In Greece, this dynamic is exaggerated by the fact that many tourists visit the islands, where contemporary political and economic events are less manifest than in Athens. I would say that in Greece, by European standards, there is a particularly great discrepancy between the apolitical idyll purveyed by the likes of Gerald Durrell and experienced by many visitors, and the exceptional grimness of its twentieth and twenty-first century history.

On this, too, I was on a steep learning curve on my first visit, when I approached it as a country that had had its rough patches in the twentieth century, certainly, but which but was now essentially one amongst other picturesque South European countries; not as rich as North Europe, to be sure, but not so different either. It was in small details that I realised that I was wrong, and that I whiffed – not so much the Middle East, as Latin America: the man with the machine gun who stood on permanent guard outside the house next to my future parents-in-law, which was inhabited by a former minister. The holes in the traffic signs part way up Mount Hymettus, which I slowly, horrifyingly, realised had been made by bullets. The ubiquity and anger of the grafitti of central Athens. The high, barbed wall which surrounded the villa of the family lawyer, despite the fact that it was located inside a gated community that was itself surrounded by a high, barbed wall. In explanation of this last, my husband told me about November 17th – a terrorist organisation named after the date of the 1973 student uprising against the junta, which had every year published a hit-list of wealthy Greeks in the national press. It was understood that if these targets left Greece, they were safe, but of those who stayed, two would be killed each year. My mother-in-law herself had witnessed two such assassinations – drive-by motorbike shootings in the Athenian distrcit of Kolonaki. All these were aspects of modern Greece that my Greece-loving friends and relatives, with their tastes for retsina and rembetika, seemed to have missed, or overlooked.

Of course, it is part of the point of the Gerald Durrell memoirs to represent pre-war Corfu as an ahistorical paradise. My Family and Other Animals and The Garden of the Gods do not mention the War at all, and the former mendaciously describes the family as returning to England for Gerald’s education (they left in June 1939 precisely because of the approaching war). Birds, Beasts and Relatives, however, ends with an elegiac letter written by Spiro the chauffeur to Margo: ‘Dear Missy Margo, This is to tell you that war has been declared. Don’t tell a soul. Spiro.’ Lawrence’s more adult memoir, Prospero’s Cell, contains an ‘Epilogue in Alexandria’ (he and Nancy left Corfu only in September 1939), which ends with a reminiscence of April 1941 when he sailed to Crete: ‘I found myself thinking back to that green rain upon a white balcony, in the shadow of Albania; thinking of it with a regret so luxurious and so deep that it did not stir the emotions at all. Seen through the transforming lens of memory the past seemed so enchanted that even thought would be unworthy of it.’ Theodore had a similar Brideshead Revisited moment when he went to fight in Crete in the same year. In the Epilogue to the 1973 Island Trails he wrote: ‘Some of the chapters of this book were roughed out while I was serving with the R.A.M.C. in the Western Desert’. He describes his 1933 touring visit to Crete with the following prolepsis: ‘Little did I guess then under what unexpected circumstances my next journey to Crete, in May 1941, was to be made. I did not see the ruins of Knossos; but I saw the ruins of Canea and the parachuted thugs who were spewed on that helpless town from the skies.’

Haag’s biography supplies some of the history which the Durrell memoirs lack –

including an extraordinary vignette of Lawrence living in Cyprus in the 1950s. He and his second wife Eva would sit at opposite ends of a table with their typewriters – Lawrence writing The Alexandria Quartet in which Eva appears as Justine, whilst Cypriot bombs shook the very windows around them. When Gerald looked into setting up his pioneering zoo on the island, he quickly realised that the political situation – of a terrorist campaign to achieve union with Greece – made this impossible. Haag notes that ‘Larry himself was nearly killed by a terorrist’s bullet and an incendiary bomb was placed in his garage’. But he does not mention the dictatorship, which was in power when the BBC took Gerald and Theodore to Corfu to film the 1967 documentary The Garden of the Gods. In this, the son of the Greek Ambassador to London, then aged ten, ran about recreating the role of Gerald of the mid-thirties. At the same time, both of Theodore’s grandsons were under house arrest in Athens.

The St Lucian poet Derek Walcott made a similar complaint about European attitudes towards the Caribbean. In his 2000 poem Omeros he mapped the Caribbean onto the Aegean, and satirised the English who saught ‘somewhere, with its sunlit islands/ where what they called history could not happen.’ Yet St Lucia’s twentieth century history has in fact been far more pacific than that of Greece. The one post-war work which has brought this turbulence into the British consciousness is Louis de Bernière’s 1994 novel Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. This describes events in the Ionian island of Cephalonia before, during and after the Italian and German occupations. Much criticised in Greece for its pro-British and anti-Resistance politics, this novel has nonetheless served the purpose of yoking the idea of Greece to some of the most terrible aspects of its recent history in the British imagination. Somewhat less-known, the 1969 Franco-Algerian film Z – nominated for Best Picture and Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards – successfully evoked the sinister Greek pseudo-democracy that preceded the 1967 coup.

When I first started visiting the country in the early 2000s, the country was a far stabler, happier place than that depicted in either of these works of fiction. Since then, it has declined again. The economy has staggered. Tens of thousands of refugees have arrived as a result of unrelated wars. Degrading acts of austerity have been imposed by the European Union, including the privatisation of coastlines, and the much-resented enforced opening of shops on Sundays. Greeks have proved powerless to effect any improvement in their situation through the ballot box. The resultant tension is manifest in behaviour that was unknown before. My husband was recently mugged by a taxi driver. I witnessed a spectacular example of road rage in Athens two months ago. Thus the anger that is glimpsed periodically in British news footage of demonstrations on Syndagma Square is between-whiles dissipated in tiny, life-degrading acts of fury. In the meantime, Mykonos has probably grown fractionally more tolerant of the barbaras behaviour of tourists who will keep its economy afloat.

And yet, despite all their grounds for complaint at the European Union, there is no significant appetite to leave it per se – only the Euro. They look upon the British decision to leave the Union with bewilderment, perceiving the British to have had the fat end of the EU, whilst they have received its sharpest end. The most conservative and wealthiest Greeks are uniformly opposed to leaving even the Euro, and thus are the more bewildered at the desire of some of their British counterparts to leave the Union itself. And – a post-Brexit Britain that defines itself as anti-immigrant might no longer be the obvious place of refuge for Greek Kings in exile.

In the light of the possible Brexit, a Greek passport has suddenly become more attractive to me. Perhaps the frailest European barque into which I might jump, the Greek one is nonetheless the one available to me. Or so I thought. It emerges that Greeks do not dispense their citizenship lightly. The website detailing the necessary residency requirements, language test, and history and culture examination, is significantly written in Greek alone. The days when the son of one of Greece’s more famous families could procure citizenship for his Anglo-German wife are, it seems, over. Thus modernised – thus EUropeanised – is Greece today, for all its current desperation. And so I am holding fire on my learning of Greek grammar. I will wait, and see, and find out where our two countries stand in five years’ time. But I also fervently hope that the Greece to which we plan one day to retire is one in which I will feel no compulsion to disengage from the historical present in order to bathe (properly clothed) in an uninformed Arcadia.