This article was published in Standpoint magazine on 24th September 2015. What follows is a pre-edited draft.

My first question, as script consultant to the BBC’s 2015 Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was – ‘cuyu bono’? The novel was found not-guilty in 1960, since when it has had half a century to gambol freely across our shelves and screens. Two of the concepts on which it turns – marriage and adultery – have lost much of their power since the 1920s. Class distinctions, though extant, carry relatively little threat to love matches which cross them. Mining and industry are now more lamented for their decline than for their inexorable rise. The flannel-trousered Cambridge intellectualism lampooned by the novel no longer predominates either among England’s rulers or its Bohemians. The world of which Constance and Mellors implicitly dream is in many respects our own. What need another replay of the struggle to achieve it? Have not this novel’s battles either been won, left behind, or reversed in aspect?

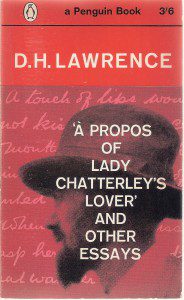

Director Jed Mercurio has recently remarked that since the novel’s struggle to represent sex has been successful, he didn’t want to labour this aspect of it. There has been much comment in the press about his adaptation’s relative lack of visual and verbal sexual explicitness, as compared both to the novel and to its earlier adaptations. But the novel’s battle was not in fact to represent sex explicitly per se, but to depict it in a way that would achieve the aim stated in ‘A Propos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, the essay written by Lawrence in the year after the novel was finished, and placed as the introduction to the second authorised edition.

The essay is a variation on Lawrence’s central theme that in European civilisation the mind and the body have become damagingly separated. The solution which it proposes is not – as elsewhere in his writings – to lose mental consciousness in ‘blood consciousness’. Rather, it is to force the mind to make a connection with the body:

In the past, man was too weak-minded, or crude-minded to contemplate his own physical body and physical functions, without getting all messed up with physical reactions that overpowered him. […] Yet they should be related in harmony. And this is the real point of this book. I want men and women to be able to think sex, fully, completely, honestly, and cleanly. Even if we can’t act sexually to our complete satisfaction, let us at least think sexually, complete and clean.

The last sentence resonates poignantly with Lawrence’s position of writing the novel whilst dying. But the sentence which precedes it makes it clear that the book is not an incitement to action (‘far be it from me to suggest that all women should go running after gamekeepers for lovers. Far be it from me to suggest that they should go running after anybody.’) Its stated aim is to be profoundly read and thought. The descriptions of Connie’s and Mellors’ ‘fucking’ – so much less realistic and vulnerable to a certain kind of ridicule on the page than in film adaptations – are not aiming at clinical mimesis, but at jolting the reader’s mind into an awareness of what sex – as approved of by the mind – is. Thus Mellors mirrors the novel’s function, since in talking sex to Connie he helps effect a similar integration in her. But her accompanying practical lessons are not, it turns out, necessary. It is sufficient to learn by overhearing Mellors and Connie’s consciousness when love-making: ‘Today, the full conscious realisation of sex is even more important than the act itself. After centuries of obfuscation, the mind demands to know and know fully.’

Of course, for Lawrence to ‘know’ sex ‘fully’ did not mean to know it as Don Juan, Swinburne or Freud knew it, but to have ‘a proper reverence for it’. In his essay ‘Pornography and Obscenity’, written at the same time as ‘A Propos’, he argues that what is considered obscene not only varies between cultures and over time, but between the judgment of what he calls the ‘mob self’ and the ‘individual self’. The former, which is allied to public opinion, is defined by Lawrence as itself obscene, because it has turned sex into a dirty secret. The innocent understanding of sex which characterised Chaucer was lost in the Renaissance, since when European art has either denied its existence (as in the art of Gainsborough), or treated it as a forbidden fruit (as in Jane Eyre). To do the latter is, to Lawrence, pornographic: ‘Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it. This is unpardonable’. It is also far more likely to incite masturbation than the ‘moderate rousing of our sex’ which is produced by, for example, Botticelli’s Venus. Hence ‘Boccaccio at his hottest seems to me less pornographical than Pamela […] or a host of modern books of films which pass uncensored’ – or vulgar seaside postcards or smoking-room anecdotes: ‘ugly and cheap they make the human nudity, ugly and degraded they make the sexual act, trivial and cheap and nasty.’

There have of course been many literary and film representations of sex as not degraded since Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and many of these are in the novel’s debt. But Lawrence was less interested in blazing a trail in art than in souls. And the latter work is, to put it mildly, unfinished – at least, if not especially, in Anglo-Saxon countries. Certainly Lawrence considered England to be peculiarly pornographic: ‘I am sure no other civilisation, not even the Roman, has showed such a vast proportion of ignominious and degraded nudity, and ugly, squalid, dirty sex. Because no other civilisation has driven sex into the underworld, and nudity to the W.C.’ Even the young Bohemians, kicking against their parents’ ‘eunuch century’, ‘have the grey disease of sex-hatred, coupled with the yellow disease of dirt-lust.’ Waxing (as Lawrence tends to) physiological, he explains that the sex and excretive functions are opposite ‘in direction’ despite being proximate – tending respectively towards creation and disintegration. In healthy people the distinction between these is sharp; in degraded people it is obliterated, and ‘sexual excitement becomes a playing with dirt’. It is obvious how strong this connection remains, especially in what is today called pornography.

Lawrence’s attempted solution is a frankness which will dispel the masturbatory ‘dirty little secret’. The giggling media reactions to such sex as there is in the latest adaptation confirm that the representation of sex is almost invariably treated as the ‘rubbing of the dirty little secret’. The ‘mild little words that rhyme with spit or farce’ (or punt or cluck) remain restricted by BBC decency guidelines which Mercurio chose not to push. Lawrence wanted us to be ‘able to use the so-called obscene words, because these are a natural part of the mind’s consciousness of the body’ – and I am sure that many a modern couple refers lovingly to ‘fucking’ and the ‘cunt’. But if what Lawrence called ‘word-prudery’ was in his own time directed at any use of these terms, it has now morphed into a fatigue at those aggressive and contemptuous uses of the words, which Lawrence himself would have shared (- and ‘even I would censor genuine pornography, rigorously’). Mercurio’s sparingness with taboo words may have in part been acquiescence with the BBC’s decency guidelines (Mercurio commented to me: ‘Currently fuck is strongly discouraged and cunt is unacceptable. They count number of uses and proximity to programme start. Every use of fuck would have to be approved at Controller level’; and the Controller might of course judge with his ‘mob’ self). But if so, it was acquiescence with a rule which in the balance of cases today Lawrence would have thought well applied.

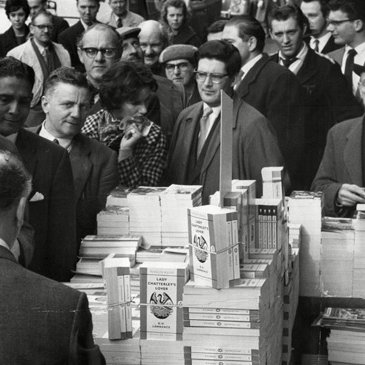

It is equally clear that Lawrence would have condemned a high proportion of the books and films which his novel’s unbanning (and its establishment of precedent for the 1959 Obscene Publications Act) helped to bring into the world. Lady Chatterley’s Lover not only didn’t shrink the volume of pornography in the world, it encouraged a deluge of it, and remains associated with it in the popular consciousness. Mercurio’s adaptation recently occasioned a newspaper article on ‘racy’ ‘period’ lingerie; ‘A Propos’ explicitly deplores modern men’s greater concentration on female underwear than on sex itself. If Mercurio was right that the battle to represent sex has been won, his decision not to reprise that victory was tactful in the light of the novel’s flagrant unintended consequences.

Yet Lawrence’s contempt for the modern Bohemian manner of taking sex ‘lightly’ also made him aware that Bohemians in his own time would condemn the novel: ‘They despise a book like Lady Chatterley’s Lover. It is much too simple and ordinary for them. The naughty words they care nothing about, and the attitude to love they find old-fashioned. Why make a fuss about it? Take it like a cocktail’. This too is echoed in the present. Holliday Grainger (who plays Connie) was recently quoted saying of the novel that she ‘doesn’t see what all the fuss is about’, and Richard Madden (Mellors) has said ‘Come on guys, we’ve got Google’; ‘There’s nothing that’s going to shock us that we’re going to do in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, is there?’ Plus ca change…but also true, and preferable to the attempt to read the novel pornographically.

Still, the novel’s contempt for Bohemianism led me to question a moment in an early draft of the script in which Connie – at the ball at which she meets Clifford – asks the musicians to switch from their sedate Classical music to ragtime. This echoed not only a similar moment in the 1987 film Dirty Dancing, but the scene in Ken Russell’s 1969 Women in Love in which Birkin mischievously asks a pianist accompanying Hermione’s Ballet Russe to switch to ragtime. This latter detail (like many in the film) was more Russell than Lawrence, and in the context of Lady Chatterley’s Lover it was even more unfortunate, since jazz is throughout the novel associated with shallowness. Tommy Dukes (the closest thing to a Lawrencian in Clifford’s Cambridge crowd) characterises modern love as ‘Fellows with swaying waists fucking little jazz girls with small boy buttocks’. Connie finds Venice as ‘almost enjoyment’, ‘all the lying in warmish water and sunbathing on hot sand in hot sun, jazzing with your stomach up against some fellow in the warm nights, cooling off with ices, it was a complete narcotic. And that was what they all wanted, a drug: the slow water, a drug; the sun, a drug; jazz, a drug; cigarettes, cocktails, ices, vermouth. To be drugged! Enjoyment! Enjoyment!’

In fact, Connie is a middle-class, cosmopolitan, highly-cultured Scot – more Howard’s End Schlegel girl than proto-flapper. I therefore successfully suggested to Mercurio that the events be reversed. Rather than Connie requesting that the music be changed from Classical to ragtime, she could be given the opposite request, and would make her first connection with Clifford whilst doing so. Similarly, I questioned Clifford’s being made to manifest indignation on discovering that his new bride was not a virgin, because it contradicted his character as someone to whom neither sex nor virginity were of much importance. Lawrence too cared little for virginity, but for the crucially different reason that he saw someone’s sexual history as irrelevant to their sexual present.

Just as ‘the mob’ has over the decades read Lady Chatterley’s Lover looking for the ‘dirty bits’, so it has watched its various adaptations. This is a risk which any adaptor faces. But there are others. It is likely that Lawrence would have disapproved of audiences watching naked actors, and would have classified their acceptance of money in order to appear naked as literal and metaphorical prostitution. He may also have classified the interaction between them and an absent film audience as an ersatz connection bearing a similar relationship to real physical encounter as First World War warfare did to sincere hand-to-hand combat. Of course, he presented naked bodies abundantly to the eye in his paintings (as exhibited, then imprisoned, in the year following Lady Chatterley’s Lover), but these remain firmly within the artistic sphere of the imitative, as the nudity of an actor cannot.

On set last October my sense of this was reinforced when seeing how abruptly the actors were moved between non-contiguous scenes. They were indeed being paid to – all of a sudden, and acording to a shooting schedule of military-style discipline – snog a near-stranger; this must perforce be done with more sang-froid than mind-body connection. Economic imperatives demanded that the lead actors be more visually attractive than in the novel, and this is of course a problem faced by all adaptations of novels of which the protagonists are not spectacular beauties. As is the way with ‘costume’ dramas, the costumes assumed a large visual importance, recalling (if not justifying) Lawrence’s point in ‘Introduction to these Paintings’ about ‘Hogarth, Reynolds, Gainsborough’: ‘The coat is really more important than the man. It is amazing how important clothes suddenly become, how they cover the subject’.

But Lawrence concedes the intrinsic difficulties of the visual medium. ‘It is easy in literature […] You can get some of the lusciousness of Hetty Sorrell’s ‘sin’, and you can enjoy condemning her to penal servitude for life. You can thrill to Mr. Rocherster’s passion, and you can enjoy having his eyes burnt out. […] But in paint it is more difficult. You couldn’t paint Hetty Sorrell’s sin or Mr. Rochester’s passion without being really shocking.’ Here he implicitly admits why it is harder for a film adaptation to achieve the aims of Lady Chatterley’s Lover than the novel itself.

Mercurio and I therefore had considerable discussions about the advisability of including oral sex. In one draft there were a few instances as performed by Mellors, and yet I thought the act anachronistic, depicted nowhere in Lawrence, and likely to have been disapproved of by him had he thought about it. Mercurio thought that there was less historic variation in sexual practice than I did, and that in any case he was adapting the novel for the present in the sexual language of the present. Masturbation we discussed masturbation similarly, and this was cut entirely, so strong was Lawrence’s condemnation of it as solipsistic, barren, and that towards which ‘pornography’ tends.

The scenes which enraged Second Wave feminists (Connie’s worship of the penis and Mellors’ disparagement of the clitoris) were not included. Much needed to be cut in order to contract the novel to 90 minutes, and in any case Mercurio felt that the novel on balance was pro-women, and that Mellors (like Clifford) was a knowing representation of aspects of the fractious, dying Lawrence.

Many viewers will not have noticed their absence. So successfully did Second Wave feminism knock Lawrence from the perch on which 1950s and 60s adulation had placed him that he is now relatively little read, and the offending passages, like the outrage about them, have been largely forgotten.

There is one final irony in the novel’s fate – subtler but no less pervasive than those mentioned above. Lawrence’s idea that profound sex is part of a good life has become distorted into the idea that if you aren’t having lots of ‘good sex’ (not what Lawrence meant by this), then you are somehow inadequate. Sex to us is a cocktail, but it is important to our sense of self-worth that we drink – or are thought to be drinking – very many very good cocktails.

And yet we are also – especially when we think about porn – beginning to wonder whether we have lost our way in our relations to sex. It might help to revisit the novel which, more than any other, got us to where we are in the first place, and which more than other tries to remedy precisely this problem. Revisiting it in this wisely restrained adaptation – or still better in its original words – we might see what medicine Lawrence was really trying to give us, and decide whether we want to – or can – take it.