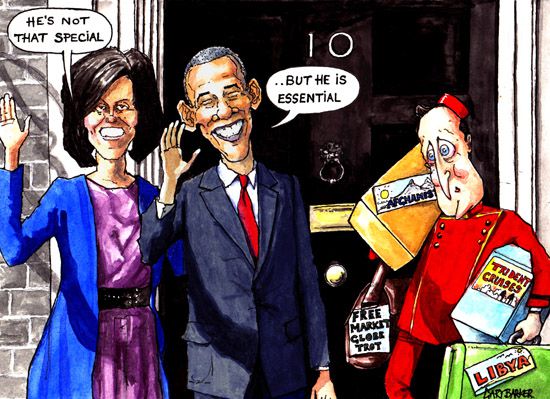

Barack Obama caused a stir in the UK’s debate as to whether to leave the European Union by repudiating – at least as far as he as President was concerned – the Brexiteers’ claim that UK-USA bilateral trade agreements would be swiftly established in the case of Brexit.

Beyond this, the USA has been unfortunately absent from the Euro-debate – not as a participant, but as a subject.

No case for staying in or leaving the European Union is complete, or indeed worth much at all, without a statement of attitude about the future of the UK’s relationship with the USA.

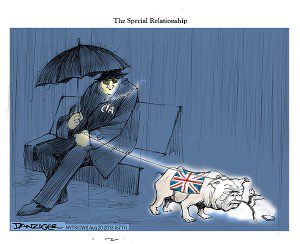

This relationship is particularly important for the UK, amongst West European countries. It is so strongly determinative of the UK’s defence, intelligence and foreign policies, that discussion of the UK’s future as a country is trivial or mendacious if it does not mention this relationship.

Such statements of attitude would reveal major splits within both the Brexit and Bremain camps – a possible reason for the subject being avoided by both.

But whichever camp wins, the most powerful elements within it will determine the immediate future of the Anglo-American relationship – therefore, from them in particular, transparency on this point would help voters to decide advisedly.

In the absence of explicit statements, one must infer.

Beginning with Bremain: David Cameron has generally been in favour of the USA-EU trade deal TTIP, whilst the Labour Party has shifted from initial support to growing hostility. The Liberals are in favour with qualifications, whilst the Greens are strongly opposed. Whatever the possible benefits of TTIP to all parties, they are weighted in favour of the US government and US corporations.

Beyond that, visions for the EU per se range from the US-phobic to the US-philiac. At the former end of the spectrum was once Charles de Gaulle, who after the Suez débacle orientated France towards the proto-EU precisely as a means of shielding it from American influence. He, and later EU politicians such as Shröder and Chirac, have aspired to pool the military resources and harmonise the foreign policy of member countries in order to constitute the EU as a significant independent actor. In 2003, Germany and France refused to co-operate with the US in its preparation for war with Iraq. At the latter end of the spectrum there are leaders from Adenauer in the ’50s, to most of them today, who see NATO and the EU as moving properly in lockstep – as they have done in the Eastward expansion of both since the end of the Soviet Union. The former is more a vision of the past; the latter is the dominant vision of the present. Hence perhaps, in part, Obama’s Europhile intervention. It is worth noting here that significant Brexiteers, such as Jacob Rees-Mogg, approve of this Eastward expansion, suggesting that that they would rather have the EU enlarged than NATO not enlarged.

Yet many of those opposed to the domination of UK foreign policy by US foreign policy hesitate to vote for Brexit. That is because they are aware of the trans-Atlanticist tendency in some of the most powerful Brexit campaigners. The EU, however friendly it might at any given time be to the United States, is at least an entity other than it, and a grouping of which the US is not part. A UK outside the EU – unless under a Labour government led by Jeremy Corbyn – would almost certainly seek stronger ties with the United States than at present.

This would take still further the voluntary subservience of the UK to US interests which began with the UK’s opposite reaction to France after Suez, which has been continued under every Prime Minister since with the exception of Ted Heath, and which was intensified under Tony Blair.

The pro-USA position is more honest amongst Bremainers than Brexiteers, if only because the former commits the UK to alliances – with its European neighbours, and with those with whom those neighbours collectively see fit to ally themselves. The rhetoric of Brexit, by contrast, centres on independence. If independence and subservience are incompatible, then – unless this movement commits to leave NATO, to require the withdrawal of US bases from UK territory, to withdraw from the current asymmetric UK-US extradition and intelligence-sharing arrangements, and to reject TTIP – such rhetoric is hollow.