Our summer holiday this year consisted of a week in Shanghai visiting a friend, followed by a week in Malaysia visiting my brother. The friend runs the China section of VTB – Vneshnyi Torgovyi Bank (Russia’s state-owned and largest foreign investment bank). The brother works for an Asian store-location consultancy from his base in Kuala Lumpur, spending half his time in Shanghai. Here are a few of my impressions, written through jetlag before they begin to fade.

Transit at Istanbul

Hundreds wrapped in white towels, bare chests and bare feet. My hallucination? No – see the jumbo waiting outside. Saudia; pilgrims. Culturally-disorientated at 3.00 a.m., I bought a plush polar-bear from duty-free.

Films

Sense and Sensibility (Iran, yet again), Grand Hotel Budapest (West China, never again), V for Vendetta (East China, unfinished and unfinishable).

Pasha Paraphrased

I was first in China in the early nineties after studying Chinese at Vladivostok, avoiding military service by getting too old abroad.

In my dorm were Communists of many nations. To relax we’d chat, play football, and drink. The only ones who wouldn’t – who stayed in the dorm reading their Red Books instead – were the North Koreans.

After that Hong Kong: study, Cambridge: MSt, London: Citibank, Cambridge: MPhil, London: HSBC, Moscow: subsidiary of Gazprom that got sanctioned, and an ongoing itch to return to China.

I took a promotion to Shanghai with another sanctioned company, brushed up on my characters, and here I am.

The Chinese have lost their way. They care too much about money. They obsess about their health but destroy their environment. Their economy is heading for a crash.

With girls it’s hopeless. In Moscow I walk into a nightclub and it’s still fine; they don’t care about your age. Here the girls are outnumbered; it’s like the reverse of post-war Russia; they have their pick and they pick Chinese.

They don’t necessarily have it easier than Japanese women though. If the Japanese do what their culture and husbands demand, they don’t need to have a job.

In China they have an ethos of good-enough. That circus performance had mistakes, but it was good enough. People will still come, because Chinese circus is so famous that everyone assumes it’s great.

After the Revolution White Russian civilian refugees came to Shanghai in a convoy of military ships. The British wouldn’t allow them to disembark at the Bund even though they were anti-Communist and dying. The officers pleaded with them to no effect. Then the officers said that, since they had nothing to loose, they would unload their entire artillary into the Bund unless their passengers were allowed to land.

The British gave way, but forced the civilians to move West beyond the Anglo-American Concession to the French Concession. Which is why you saw a (repurposed) Orthodox Church a few streets from here yesterday.

Today the Chinese are ok with the Russians. Also with the Americans, who they just see as business partners. It’s the Japanese and the British that they have problems with. So US citizens get ten-year multi-entry visas whilst UK citizens get two years.

See Shame, below.

Former St Nicholas’s Orthodox Church, Shanghai

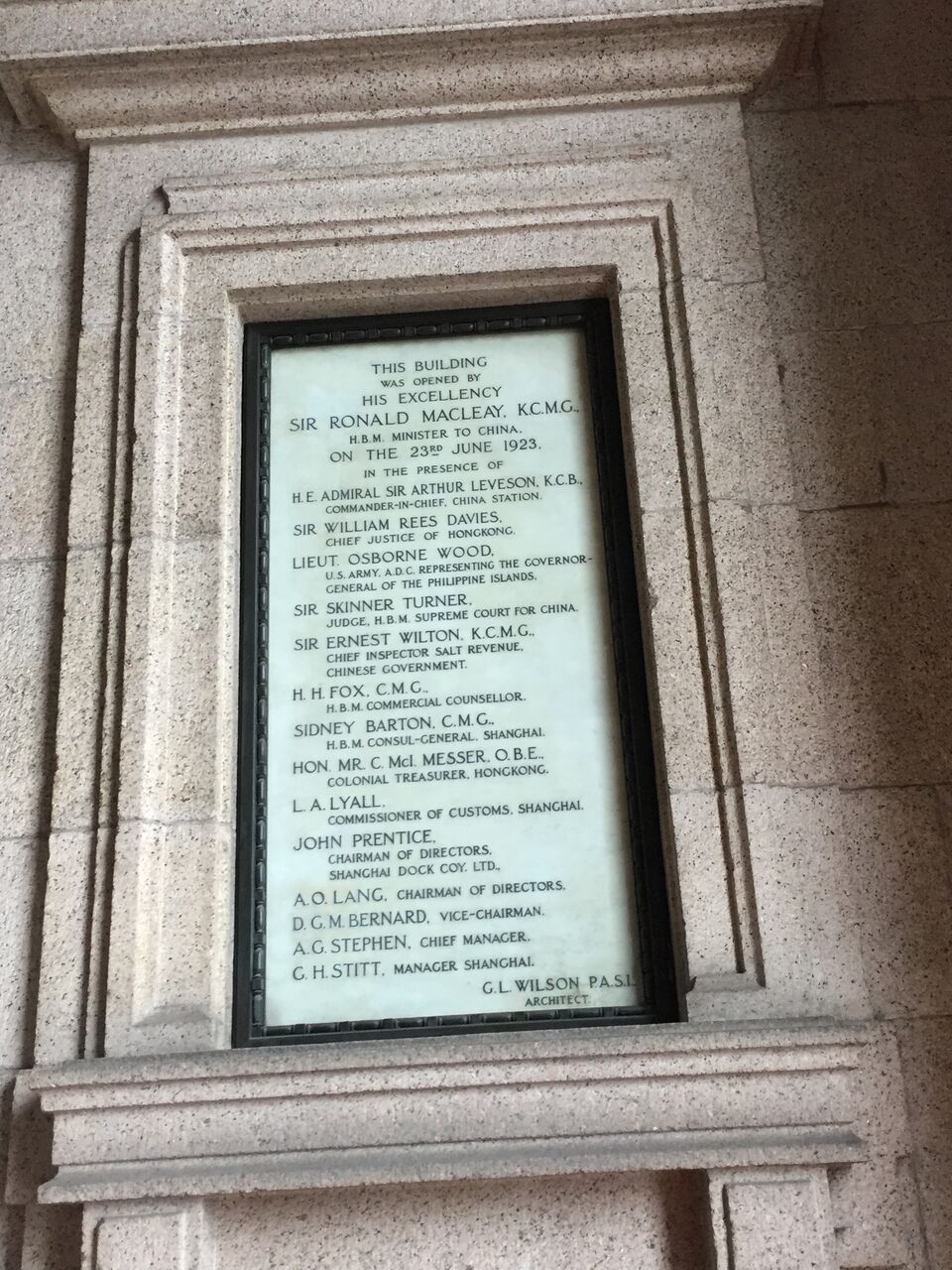

The original headquarters of HSBC, Bund, Shanghai

The current headquarters of HSBC, Pudong, Shanghai (immediately opposite the preceding photograph)

The Future

The Chinese have an app which combines Facebook, Amazon, Whatsapp, Apple Pay and Paypal. You can send a text to a friend that includes money. At any restaurant you can pay by phone. Shanghai is close to being cashless.

Unless you are a visitor.

Mastercard, Visa, etc. are not accepted in many places, because they drain money out of China to America.

To get the app you have to register with a photo of yourself next to your passport page and your Chinese residency permit.

And so we relied on cash more than in the UK, and were excluded from the app-only-operated massage chairs at Pudong International Airport.

Control

Mao, and Xi Jinping, are hardly visible (there was one Mao over the entrance to a restaurant). The control is similarly subtle.

The app mentioned above tells the government much, as do emails and texts. The Chinese enjoy telling each other stories about how the authorities have come down on individuals for their internet use. A husband and wife once texted each other about meeting up, and in a non-political context used the word ‘demonstration’. Within an hour, the police had visited them both.

Local or foreigner, you show your passport to buy train tickets.

At churches, Chinese and foreigners must attend separate services.

Facebook, Twitter, Google and Google’s subsidiaries (such as Gmail) are all blocked. Virtual Private Networks were tolerated because they were used mainly by foreigners, but are now also restricted, and may shortly be banned.

It is expensive for foreigners to get a local driving license, and hard for them to buy real estate. (Pasha is bemused at how easy England, by contrast, makes it for foreigners; he is thinking of investing in a London house).

As the head of a foreign business, Pasha may not watch porn, nor help someone else to access a prostitute, nor commit any number of business offences. In practice the laws are applied according to how favourably the government views the employer. Pasha could face anything from a revocation of residency rights to death for breach of the law. The CEO of a Western chain of shops in China once faced prison because a promotion had caused a stampede in which some customers were injured.

I lay down briefly on a bench on the Bund, exhausted by the walk along Nanjing Road from People’s Square. Within seconds, a policeman had told me to sit up.

Pollock

In Xintiandi one night, three visiting Vladivostokers. Partners in an advertising consultancy, they were in Shanghai to introduce their newest client’s product – pollock roe – to the Chinese market. We ate at a Japanese restaurant where the first course by chance included precisely this roe. The problem, they explained, is with breaking out beyond the Japanese restaurants. That’s a challenge, said Pasha. The Chinese know what they want to eat. It will be hard to change them.

Suns

The Chinese Lenins are the Suns, except that Yat-Sen died two decades before Communism triumphed, came to Communism gradually, was humane, and isn’t embalmed in his hill-top shrine above Nanjing to which the Chinese continue to make pilgrimage.

Soong Ching Ling’s widow’s residence was the first place we visited in Shanghai, followed by their married home. I was moved to see how much the (well-Englished) commentary stressed their mutual love and the happiness of their brief married years.

True to the East Asian penchant for couples’ gifts, a his-’n-hers watch set was for sale in the Sun Yat-Sen gift shop – his with a tiny profile of Sun, hers with a tiny profile of Soong.

The Soong sisters are the Chinese Mitford sisters. Ai Ling (1888-1973) married China’s biggest gangster, H.H. Kung, Mei Ling (1898-2003) married the brutal nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-Shek, and Ching Ling (1893-1981) married the admirable founder of the Kuomintang. As a popular phrase of the time had it: ‘One loved money, one loved power, and one loved China’.

We have worn our matching watches since that day.

Brands

If you want to buy a Vacheron Constantin watch in Shanghai, there are about six different shops in which to do it. These are mainly in malls, which are for the most part empty. All it takes is for a couple of people to spend $20,000 each in a shop per day for them to tick over. Nowhere have I seen Western luxury brands so fawned over, along with (and here’s the contrast to Moscow) a decent number of billionnaires around to buy them. Pasha has a Bulgari watch which he bought before his move to Shanghai to impress Chinese business associates and girls. He confesses that he doesn’t know how to set it to the right time, its face is so complicated he can’t tell the time anyway, and every few months it breaks down, to be repaired in London at a cost of around £2000.

Prices

| Tip for anything

|

£0.00 |

| Single metro ticket

|

£0.35 |

| Fifteen minute taxi ride

|

£2.00 |

| Bottle of tepid water (the Chinese believe that cold water is bad for your health) | £0.30 multiplied manyfold: you need water just to walk down the street in summer, and the tap water, even boiled, is toxic

|

| Nice restaurant meal

|

£12 |

| Return ticket for an immaculate high speed train to Nanjing, 300 km from Shanghai

|

£50 |

| Small pot of tea pretty much anywhere

|

£8 |

| Cashmere jumper from a department store on Nanjing Road East that looks, and sounds from its music, like a British Home Store c. 1970

|

£330 |

| Jade bangle

|

Anything from £80 to £368,000, the differences between them being opaque. ‘Origin’, ‘quality’, and ‘age’ are all vaguely mentioned by those I ask, without indication of how any of these can be identified. See below. |

Bangle in a shop window on Nanjing Road East, c £129,800

Another bangle in a shop window on Nanjing Road East, c £285,800

Another bangle in a shop window on Nanjing Road East, c £368,000

Squatting

It’s so much more hygienic, Western partisans of this arrangement explain. It is not, I have concluded. One splashes oneself. The floor is nastily wet. Backs of unknown women’s thighs hold no terror for me by comparison. And why, when the move is made to Western-style hygiene, is it so uneven? In the futuristic toilets of the luxury IAPM mall the toilets double as electronic bidets, but there are ancient and insufficient soap dispensers next to the futuristic sinks, and inexplicably unlidded waste-baskets in every cubicle. Next to the electronic driers, a sign instructs one not to spit.

IAPM Mall in Shanghai (2014)

Jjimjilbang

The world’s greatest fetishisers of hygiene, it turns out, are the Japanese and the Koreans, not withstanding their squat toilets. I have learned this through my Korean sister-in-law, who has long since educated my brother out of his gross European ways. On the eve of their wedding we went to a jjimjilbang in Seoul – a charming experience, available all night, slotting delightfully into an evening on the town. So after days of sweating round Shanghai, and given the absence of any Chinese public bathing culture, Pasha took us to Shanghai’s Korean baths.

The first hour was predictably boring. I lay around naked and alone, whilst Pasha and my husband sweated in company and talked men’s things. Then we met in shapeless cotton uniforms on the unisex floor, and moved from infrared caves (what are their health benefits? I asked; This is the kind of situation where you don’t ask questions, Pasha answered), to an ice-covered un-sauna, to a cave where we lay around on rock salt, to a restaurant where we hunched over a low table piled with Korean food and beer. From this I absconded for a massage, vaguely wondering how unfamiliar were the protrusions and muscles of my giant pale body laid out on a slab for – I was pleased to discover – the oldest masseuse, whose hands had gained strength over time, and knew what they were doing.

Thank you Korea, I thought as we left.

Food

Saturday Turkish Airlines then Eastern Chinese Sunday Suzhouese then Yunanese Monday Starbucks then Japanese Tuesday Western healthfood then Uighur Wednesday Western healthfood then Eastern Chinese Thursday dim-sum then Japanese Friday Shanghainese then Korean Saturday street food then Italian; Pasha insisted we needed it by then.

The best: Meilongzhen Restaurant, extant from the inter-war years, now government-run and over-lit but still redolant of the thirties and of Sun, Kai-Shek, Kong, and other worthies and unworthies who have eaten there.

The outcome: nothing fresh – neither fruit nor vegetable – made any kind of appearance; my husband had traveller’s diarrhoea for a week; I became constipated.

Decoration at Meilanzhen Restaurant

The Uighur Restaurant

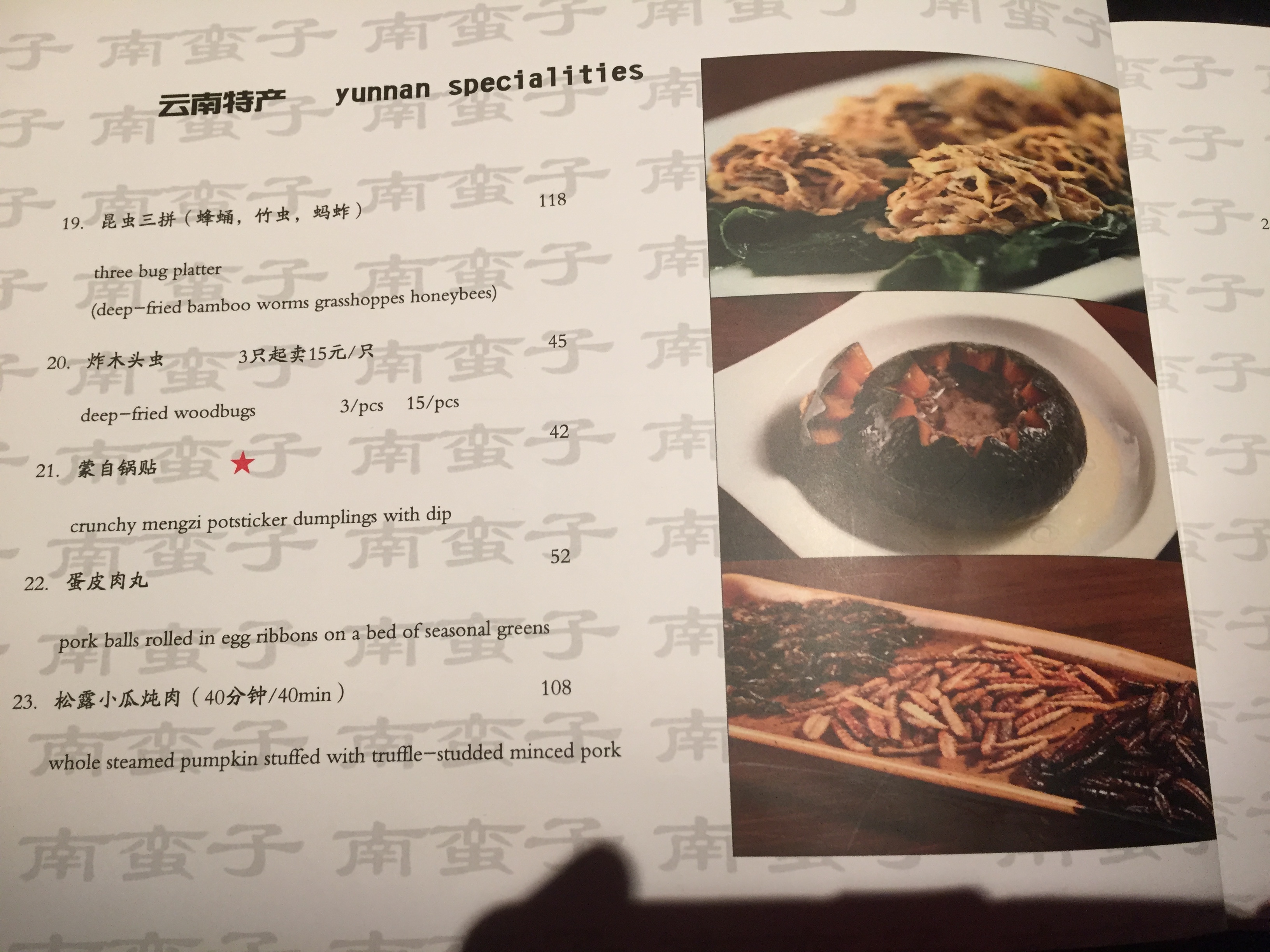

Menu at Yunanese restaurant, Southern Barbarian

Shame

Don’t buy that, said my husband when he saw me looking at one of the many reproductions of the inter-war paintings of pretty Chinese girls in the tight semi-Westernised dresses that were not invented until this period, it reminds me of something ugly. Of the opium wars that roused huge opposition even in Britain at the time but which the British have long since forgotten, of Huangpu Park that excluded dogs and unaccompanied Chinese, of the bars, the brothels, the Shanghai-whore-of-Asia, the racetrack on what is now People’s Square, of the attempt, which came frighteningly close to succeeding, of turning China into another India, and of the fury that it did not succeed, but rather produced Communism.

Inter-war advertisement

British worthies honoured on the Bund

Rare sighting of Marx and Engels, Fuxing Park, Former French Concession

On the far side of the Cultural Revolution, Shanghai is again full of Western goods, Western restaurants, Western(ish) capitalism, the Western language (in places), and of Westerners.

On Chinese terms, this time.

Gardens

After a while in Shanghai one begins to wonder where history has gone. It’s a young city, for sure – but there is a pre-revolutionary town, just West of the Bund, centred on a retired Ming civil servant’s Yu Gardens. Many more such in lovely Suzhou, of which the best garden belonged to a self-declared Humble Administrator. These enchanting adventure playgrounds for grownups to sit about and write poetry in are much needed. The 100 km train ride from Shanghai across the Yangtze delta reveals hardly any space between the factories and surrounding houses. Ditto Nanjing, 200 km further.

Geography Lesson

Visiting a friend in Shanghai and thinking that it would be a good idea to combine this with a visit to a brother in Kuala Lumpur is like someone in Kuala Lumpur visiting a friend in London and thinking that it would be a good idea to combine this with a visit to a brother in the Urals city of Ekaterinburg. The flight South took five and a half hours, and all we covered was a corner of South China and the Indo-Chinese peninsula. Maps don’t cut it; one needs a globe.

Being British

Being white cuts no ice in China, but I heard a whispered echo of Malaya as the doors of Kuala Lumpur’s Majestic Hotel swept open for us to take the most delightfully high of high teas.

Trickle-down

From the palm-shaded fifty metre infinity pool at my brother’s apartment complex I look through the fencing to the less perfect housing below and wonder about the possibility of a causal connection. My agitation makes water overrun the side.

Batu Caves

Coming to Malaysia I was ill-informedly expecting roughly one culture, not many. But the British brought in Chinese to do business, and Indians as labourers, and the result is that this Muslim country – more heavily-hijabbed than a few years ago, my brother told us – hosts many Chinese and Hindu temples. One of the latter is at Batu Caves, 17 km to the North of Kuala Lumpur, to which we were attracted partly by the Forsteresque name. But this temple, dedicated to Murugan, is modern, dating from 1890. Each January or February it is the focus of the Tamil Thaipusam festival for the atonement of wrongdoing, at which men will pierce their bodies and drag or carry vats of milk from the city centre to the caves, and up its steps. Inside, it turns out that new shrines are still being added, scattered here and there about the inner rock face. The mood is festive. Men and women sit barefoot in the shrines and chat. Or feed the monkeys, which are ubiquitous, matter-of-fact, and bold (see Monkeys below). A nearby cave is secular – I could remove my borrowed leg-covering – and the focus of conservation. On the guided tour I learned the meaning of ‘twilight zone’ – the part of a cave between the entrance and the realm of pitch black. Between the secular and the sacred, the people and the monkeys, the darkness and the light, I reeled.

Batu Temple of Muruyam

Batu Temple

Macaques and me

Light in the Dark Cave at Batu

Melaka

Formerly Malacca, as in Malacca suger and Malacca cane and straits of Malacca, facing Sumatra. Here is where one goes for history, KL being almost entirely post-war; along with Singapore, this was a major trading port well before the Portugese reached it.

Hungry Ghosts

We visited Melaka on the first day of the Festival of the Hungry Ghosts, which meant that the temples of Tua Pec Kong (who looks after the souls of the dead, and whose temples are often found near cemeteries) were doing considerable business. The ghosts were being fed the huge fruits on the altars. How badly we do death, I thought. How wrong we are to have misplaced All Soul’s Day, and to have turned the eve of All Saints into the offensive banality that is Halloween. Our own ghosts are hungry too, and we are likewise hungry to feed them together.

Temple of Tea Pec Kong, Melaca

Food

Sunday Asian Airlines then English high tea then Malaysian, Monday Indian then Thai, Tuesday Chinese then Thai, Wednesday Bornean then Eurasian, Thursday Bornean then Eurasian, Friday Eurasian, Saturday snacks from Malaysia’s various ethnicities then sister-in-law’s pasta, Sunday Malaysian then Vietnam Airlines.

The best: fresh fruit, wherever I could get it.

The outcome: my husband got better; I ate too much fruit and got diarrhoea.

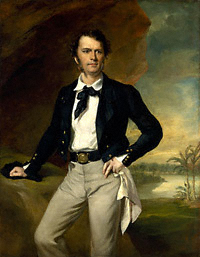

White Rajahs

It turns out that Sarawak – that huge chunk of North-West Borneo that is Malaysia – was not part of the formal British Empire until after the war, when it was colonised for an unhappy couple of decades before independence. Rather it had been ruled by three generations of the Brooke family, known locally as the ‘White Rajahs’. Remarkably, the Brookes were sensitive to local culture, caused relief by extirpating headhunting, and are now warmly and proudly remembered. The Eurasian restaurant at which we dined on each of our three evenings in Kuching, Sawarak’s capital, was called the James Brooke Bistro, after the first of them (who reigned 1842-1868). One of those to speak warmly of them was our guide to the jungle, an Iban called Richard, who claimed that his grandfather had hunted heads – which would mean that it was not extirpated until the early twentieth century. This practice, we learned, was principally a young man’s pursuit. The status of women being relatively high, a young man did not reach sufficient status to marry until he had brought a head back to his longhouse (an appealing version of communal living). A longhouse’s accumulated skulls would be housed in a ‘headhouse’ and appeased by sacrifices of food. The arrival of a new head would help to bring a house’s period of mourning to a close, suggesting a vicious cycle in operation between rival tribes as tit followed mourning followed tat. Today the Sarawakians live in peace, united in their pride in the Brookes and anger at the peninsular Malaysia which they have only recently joined, and which they perceive as giving too little in exchange for their oil. ‘In KL they laugh at us for living in trees, whilst they live on our oil’. In which there is some truth.

James Brooke (1847), 1803-1868

Jungle

My image of jungle was that of Henri Rousseau, who never left France:

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910)

It turns out that there are jungles and jungles, and I was thinking more of the Amazon. So my response was tinged by anticlimax. No big cats. No big snakes. Little big foliage (how was it possible that many of the trees could pass as English?). Hardly any flowers (save one that is the biggest in the world). And hardly any sun. The clue is in the name ‘rainforest’, I guess – but still, where was the cliché? Only the blowpipe-shooting Penan warrior at the cultural village. Reality was more subtle. The tropical pigs, with their wonderfully enormous and wise faces. The solitary youthful crocodile. The sudden contrasts between different kinds of jungle. The mangrove swamp suddenly walkable with the withdrawing tide. The English-style changes of weather. Why, I wondered, are the Middle East and places of similar latitudes so much hotter and sunnier than the tropics, even when they are next to the sea, as in Dubai? A puzzle I have not yet solved, and another example of opposites meeting.

The closest it got to Rousseau

The wonderful pig

The Penan warrior and his blowpipe

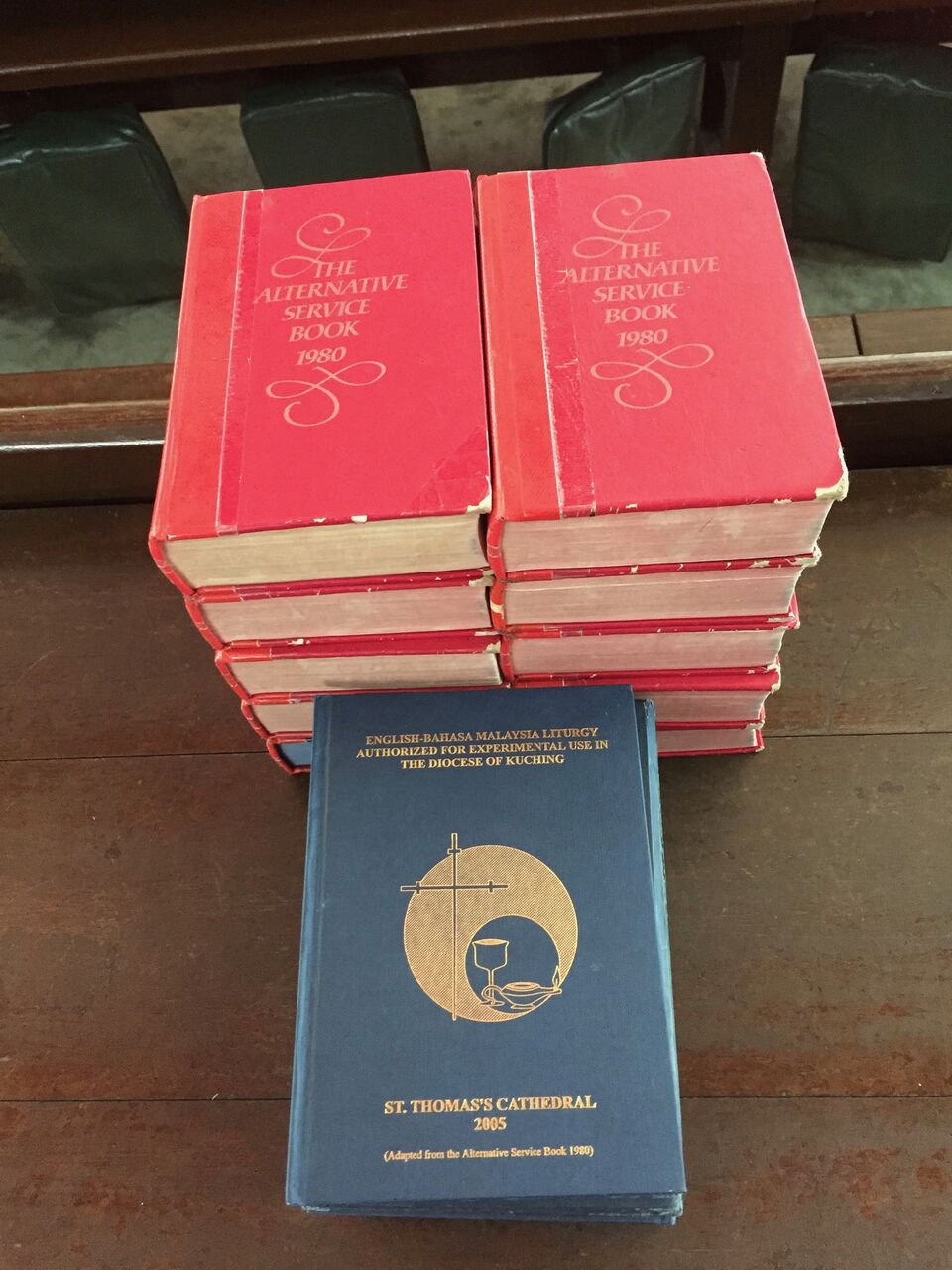

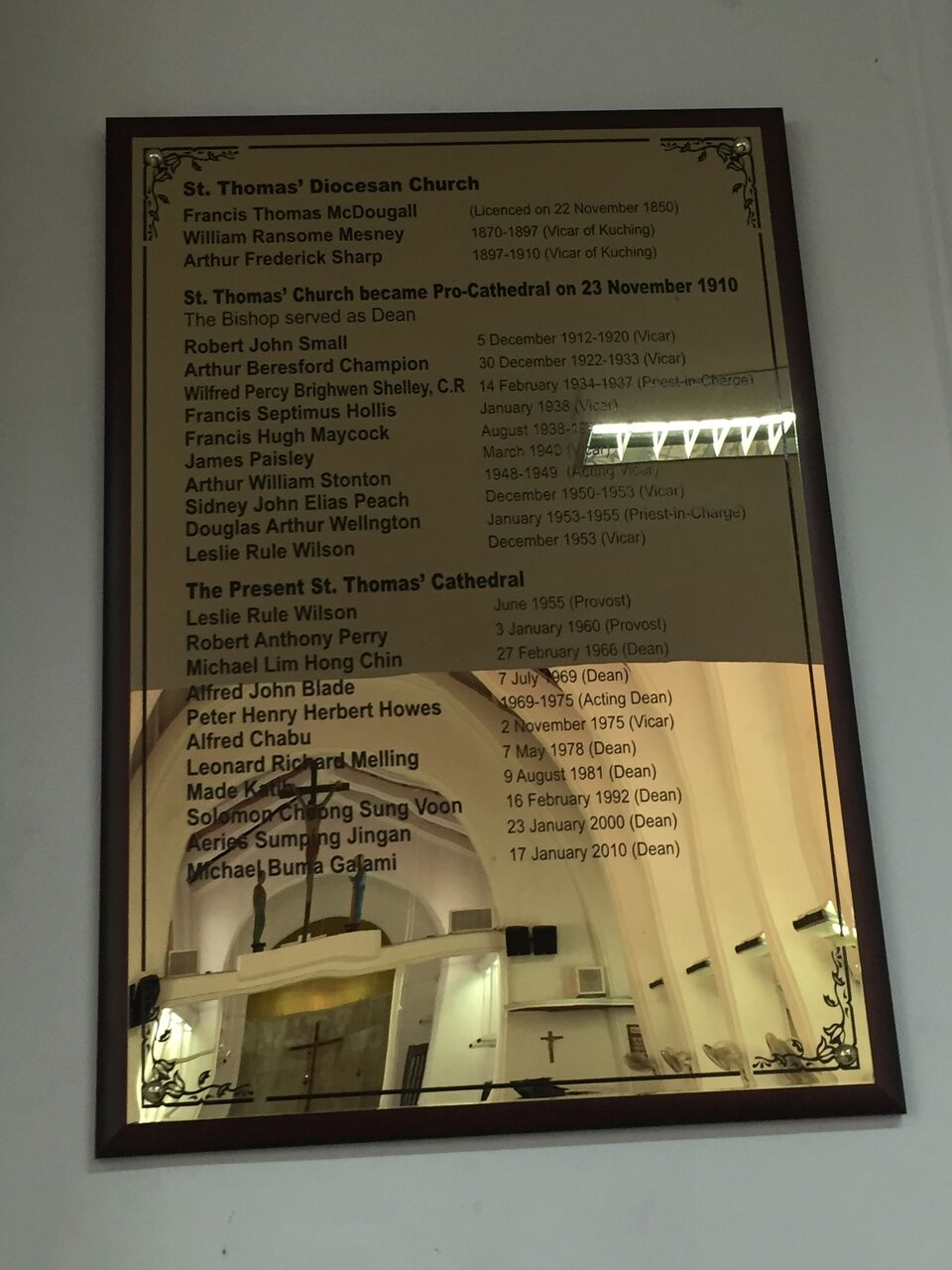

Churches

At Christ Church, Melaca, St Thomas’s, Kuching, tropical Christianity thrives. The newsletters of the latter make it clear how busy the Cathedral is, with women’s groups and Bible groups, retreats and exchanges. The Right Reverend Donald Jute spent some time ministering in the UK. He writes: ‘The Church in the UK is very different from our local Church here. Many churches are attended only by elderly people. It was an honour, joy and privilege seeing life being breathed into the four congregations/churches at Milngavei, Bearsden, Drumchapel and King’s Park, Glasgow where I served. Liberalism is a big challenge. The Church must hold firmly and faithfully to the Word of God in the Bible. […] We cannot simply interpret the Bible to suit the agendas or desires of certain people.’

Sarawak is predominantly Christian, mainly thanks to the Brookes (and in the one Muslim village we saw, headscarves were not worn). In China, by contrast, the hold of Christianity is weak. When the Jesuits were received by the Ming emperors, and made it clear that their faith was incompatible with the Emperor’s worship of Heaven on which the fate of the Empire relied, it was rejected. When Protestants such as Eric Liddell later tried the opposite tack of converting from below, they arrived alongside the bitterest forms of colonialism, and were rejected in favour of Communism. Nonetheless, there was an Anglophone church near Pasha’s Former French Concession apartment. The ministry of the saintly Liddell, who died in a Japanese prisoner of war camp five months before liberation, was not without any effect.

List of incumbents at Christ Church, Melaka

St Thomas’s Anglican Cathedral, Kuching, Sarawak, Borneo – rebuilt in the 1950s

At St Thomas’s

List of incumbents of St Thomas’s, Kuching

Monkeys

Seeing monkeys and apes raises questions of definition and of moral status. The macaque monkeys steal my bananas and my nuts. I pull back, but they are more determined than I am. Ritchie (b. 1981), the alpha male orang-utan at Semenggoh reserve in Borneo, apprently ripped several fingers from his closest rival in establishing his dominance. May we judge? Those unfamiliar with them don’t. Those familiar with them do. Yet even to describe the proboscis monkeys as beautifully calm and unassuming, with their pot bellies and big noses and constant pink erections, is to begin to judge the macaques by contrast. The orang-utans may not have blowpipes, but would overwhelm any of us in combat if it came to it, which would only ever be our fault. Their relaxed position is sixty feet up, hanging from one hand, eating bananas with the other – surely the origin of the phrase hanging around. Had the Americans seen them?

Hat

Over the rail of the VIP balcony at the Sarawak Cultural Village’s cultural performance theatre the hat of the visiting former President of Nigeria Goodluck Jonathan was just visible. According to the Chinese woman sitting in the Chinese hut as an example of the Chinese people, his wife was delightful. And later this year, unnamed British royalty are to visit too; British security has already scoped the joint.

Rising Sun

It took a visit to the Far East for me to begin to understand the Eastern Second World War, of which I was as ignorant as Burma vets complain that the English generally are. You cannot visit Nanjing – ‘raped’ when Nanking – or the Shanghai architecture described in J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun, or the relatively-benignly-occupied Malaysian peninsula, without wandering about it. And you can’t see the Bornean mangrove swamps without imagining what it would be to enter them, on foot, as a Japanese or British soldier, facing many alternative sources of death, not the least of them dehydration. If the First World War felled the least imperialist of the European empires, the Second World War felled the most.

But so many contradictions:

Hitler admiring an Asian people (the Japanese as ‘honorary Aryans’), the Japanese colonising Asia in the name of anti-imperialism, the British first supporting the Japanese as anti-communist buffers to the Soviets, then fighting to reimpose their empire in the name of democracy even whilst facing existential threat in Europe, the Americans destroying British imperialism to the end of establishing the British-style informal imperialism which they have pursued ever since, the Chinese being finally put on the same level as the Europeans when the Japanese entered the Concessions after bombing Pearl Harbour, the Russians entering the war against Japan in the last three weeks of the war in violation of the cease-fire that had ended their war in 1939 thus helping to re-establish Western colonialism, the Japanese offer of a conditional surrender being rejected before Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed even though the ‘unconditional’ surrender that followed left Hirohito in place, the fact that the British accuse Japan of failing to get to grips with its past whilst books about the Burmese War tumble from Japanese presses and the British not have not even begun to properly discuss their own empire.

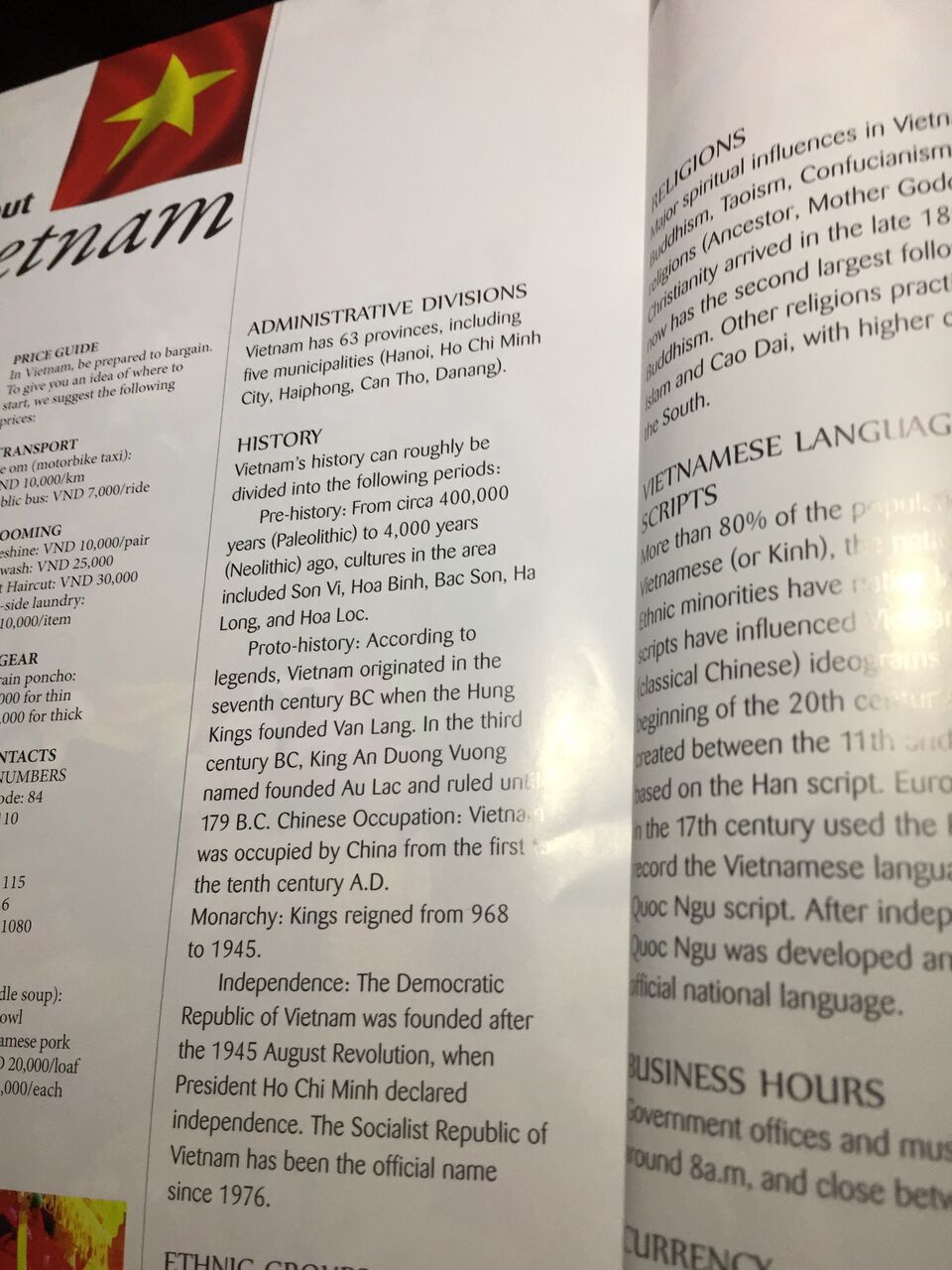

Transit in Ho Chi Minh City

Middle of the night, crocodile skin wallets, belts, handbags, and sandals. No vegetarian sandwiches. Vietnam Airlines making no mention of the French or of the war in its magazine’s potted history, but offering fifteen communist films to watch. To every barrista, handbag seller, waiter and steward I wanted to apologise, and to ask ‘Are you ok?’

Summary of Vietnamese history in Vietnam Airlines’ onflight magazine

But how and where to begin?