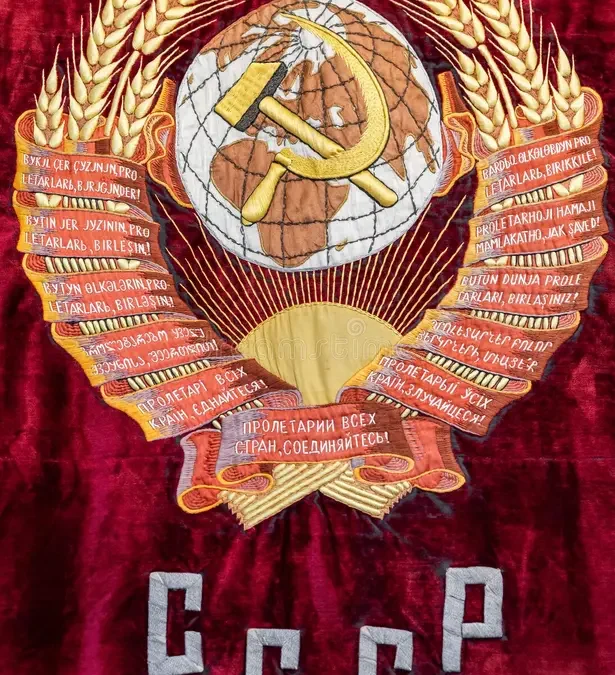

A couple of Sundays ago I was in the Gulag. Or, to be accurate, in a memorial on the site of a former Soviet kolonia. The ‘colonies’ were mini versions of the lagers which were administered by the Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei – Main Camp Administration, or GULAG.

Perm-36 operated on its current site – two hours’ drive outside Perm in the Western Urals – between 1946 and 1987. As a forced labour logging camp, it was at its harshest before Stalin died. It interned regular criminals, but also became the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic’s major camp for dissidents. In 1994 a history Professor at Perm State University, supported by the human rights group Memorial, successfully campaigned to make the camp a museum. Recently the camp has controversially been taken out of local and into central government control, so that the Professor – who was our guide – is no longer involved in its administration.

The night before this visit, the English party of which I was part gathered in the lobby of Perm’s Ural Hotel to drink champanskoe to Jeremy Corbyn’s victory. Earlier that day, we – Mary-Kay Wilmers, Jeremy Harding, Karen Hewitt, Alexander Mercouris, John McRae, David Edgar and myself – had gathered round my laptop to watch the Labour leadership election results live on Sky. Fortunately, our sentiments coincided.

But once our bottle was empty, our conversation turned to the next day. Since visiting Gulag sites is a rare thing to do, whereas visiting Nazi concentration camp sites is not, we discussed the former by analogy with the latter. And on this, it turned out, our views differed. One of us was strongly opposed to all visiting of concentration camps, but not of Gulag sites. Others of us put forward reasons for, and defended the permissibility of, visiting either.

I spoke from fourteen years’ experience of taking American tourists on cultural tours of Europe. All of the tours which included Munich included Dachau KZ (Konzentrationslager). I had therefore had some time in which to develop my Dachau spiel. It had settled down to this.

I would summarise the history of the town of Dachau, and of its Nazi camp. I would try to shed light on the period by sharing the varied experiences of my German family members. Finally, I would say that it was wrong to visit Dachau if it did not make us ask ourselves ‘what similar is happening today?’ And ‘what can I do to stop it?’. Otherwise, we would resemble German tourists visiting British Boer War concentration camp sites in the 1930s and bemoaning past, specifically British, evils. Since my guiding days included the worst days (to date) of the War on Terror, my final comments were pointed. I don’t know if the points were felt, but they were never objected to.

The drive towards the camp, on a fine September day, lifted us out of Perm’s plane to the West of the Urals into the hills themselves – gently rolling, forested, and sequined with little lakes. The camp itself is relatively small – partly decayed, partly neat with exhibitions, and partly, unexpectedly, up-to-the-instant with QR codes.

Over his four-hour tour, the Professor gave us much detail about the camp’s former conditions and inmates. But there were some details that puzzled me. Or, rather, the mode in which they were presented and received puzzled me. We were shown the perimeter fences – variously barbed, electrified, and overwatched – and the visiting room, in which prisoners and their guests were separated by glass, and a guard was always present – and the post room, where all post to prisoners was opened before being passed on. I was struck that all these features characterise UK prisons today.

It may, of course, be wrong to have prisons. But if it is not, then these are necessary measures in running them properly – and we should not confuse the morality of prison conditions with the innocence or guilt of those who are interned.

Towards the end of our tour we passed a truck which had been used for transporting prisoners to the camp. It was explained to us that its hold had no windows, so that the prisoners would not be able to see where they were being transported. I couldn’t help turning to David Edgar and saying: ‘at least they didn’t also tape their eyes shut, put eye masks and earphones on them, truss them up like chickens, and tie them to the bottom of an aeroplane’. (The Soviets, like Americans today, used the term ‘extraordinary’ to refer to their harshest modes of operation).

One of England’s greatest playwrights, and a wise and wonderful man, turned to me in some irritation. ‘There is a certain kind of whataboutism that I find sinister. Catherine, it was awful’.

I retracted and retreated. For a long time, in the solitary confinement hut, I digested this. And then I decided that I needed to respectfully spit it back out. On the dusty track from the hut to the exit I conceded to David that, had we been visiting a contemporary, and let’s imagine appalling, Russian prison, then a comment about Guantanamo Bay might have constituted an inappropriate ‘what about’. As it was, I stuck by what I had said the night before. Let none of us visit such places without thinking of what we can change. And on this, I’m glad to report that one of England’s greatest political playwrights agreed.