This article was published in Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies Volume 7, No. 1, December 2024, pp. 287-98. It develops the findings of a meeting of the London Lawrence Group meeting recorded, with illustrations, here. Thanks are hereby recorded to Natasha de Chroustchoff for her help in setting the historical record straight by presenting her father as an important source of D. H. Lawrence’s knowledge of tribal art, as well as the original of the character of Maxim Libidnikov in Women in Love.

Abstract

D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love (1919) contains one of literary modernism’s most notable discussions of ‘primitive’ art. Women in Love being clearly a roman à clef, some attempts have been made to ascertain the model for the ‘young Russian’, Maxim Libidnikov, who informs this discussion – hitherto without success. This article summarises my finding of that model – one Boris de Chroustchoff – who paid Lawrence, and therefore modernist literature, the service of introducing him to African traditional art. The methodology is my interview of Boris’s daughter, Natasha, and background research in the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, and relevant literature. The result is not only that a conundrum in Lawrence studies has been solved, but light has been shed on the kinds of means whereby modernist authors were made aware of, gained access to, and were influenced by, traditional art.

One of the denizens of Women in Love’s London Bohemia is the “young Russian” Maxim Libidnikov. The editors of the 1987 CUP edition, John Worthen and Lindeth Vasey, suggest that his name derived from Lawrence’s friend Maxim Litvinov and that the character himself “may be a recreation of Heseltine’s friend Nichols” (WL: 538). My 2019 essay in this journal considered and dismissed the Robert Nichols connection, but pursued the Litvinov angle as a means of tracing Lawrence’s shifting relationships to Russia and its politics from 1914 onwards.[1] My research also identified a Boris de Chroustchoff as a possible model for Libidnikov, but I did not develop this speculation (although I did argue that Libidnikov is clearly not a revolutionary, and more likely to have been on the side of the Tsar’s Embassy in London than that of the Soviet Embassy eventually set up by Litvinov with his wife, Lawrence’s friend Ivy Low). I have since become acquainted with Natasha,[2] daughter of de Chroustchoff, who convinced me that Libidnikov is indeed modelled on her father. The meeting of the London Lawrence Group of 18 November 2022, in which I interviewed Natasha about her father, forms the basis for the following addendum to and correction of my 2019 JDHLS article.

Natasha began by giving an overview of her father’s life. The name de Chroustchoff (to which “de” was added when it was transliterated from Slavonic to Latin characters at a time when aristocratic Russians chose to fashion themselves as French) would in Russian be spelled the same as that of the former Soviet Secretary General known in the West as Khrushchev – Хрущёв – although there is no known connection.

Boris was a member of a patrician family which lived in the Ukrainian territory of the Russian Empire. It can be traced back to the first Chroustchoff who arrived from Poland at the end of the 15th century, and whose military support of the tsar was rewarded with land and status. In the nineteenth century there existed a distinguished Crimean War general named Alexander Khrushchev (1806-75). Boris’s family was cultured, liberal and Westernised, based in a manorial estate in the Kharkov region. His father Alexander studied at the University of Heidelberg before returning to run his estate. His mother Maria was the daughter of a professor of agronomy at the university of Kharkov; her portrait was painted by Dmitri Kardovsky.[3] Together they hosted Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko and Russian artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Alexei von Yavlensky. A character called Chroustchoff is the eponymous demon in Chekhov’s play The Wood Demon.

Boris was born in 1892. He had an older sister and brother; the three apparently had an idyllic childhood, and spoke Ukrainian. In 1900 the family moved to Munich for its art, and the father opened an artists’ studio. (After the Revolution of 1917 the extended Russian family disappeared from view; although in 2021 Natasha discovered via the internet that the derelict family house in Ukraine still existed. She believes that prior to the 2022 Russian invasion there were plans to restore it, following a resurgence of interest in the manors of Ukraine and their tourist potential). In Germany Boris’s parents’ marriage broke down, and his brother died. His mother and sister returned to Russia, whilst Boris and his father moved to Switzerland (the father marrying the family’s Scottish governess), where Boris became an alpinist. He was then sent to Harrow School, and in 1912 went up to Lincoln College, Oxford, to study for the (relatively new) Diploma in Anthropology. His main interests lay in ethnography and ethnology; he was already a collector, and made several donations to the Pitt Rivers Museum.[4] However, for reasons that included overspending, a lack of diligence, and the War, he never completed his Diploma.

In 1914 he met Philip Heseltine (professional name Peter Warlock, model for Julius Halliday in Women in Love) through the Oxford Society for Psychical Research. Boris claimed that for many years he was Philip’s closest friend. Rhian Davies (music historian and expert on Peter Warlock), who was present at the meeting, pointed out that he dedicated his song “Mr Belloc’s Fancy” to Boris in 1922.

For a time the two men shared flats in Chelsea and Maida Vale with an Indian manservant who produced Indian meals (which Boris loved). They frequented the Café Royal on Regent Street along with Minnie Lucy Channing, the Puma, on whom the character of the Pussum is based, and Heseltine’s future wife.[5] Boris was working as a postal censor for the War Office, since he could speak several languages. It was in his and Heseltine’s flat that, Natasha believes, Lawrence first encountered tribal art, of which Boris (de Chroustchoff) had built up a large collection by buying from specialist dealers. Of this collection Natasha has inherited all that survived the Second World War.

Asked whether Boris and Heseltine actually went about naked in their flat, as Libidnikov and Halliday do in the “Fetish” chapter of Women in Love, Natasha responded: “I’ve no idea, but if they did it would hardly be surprising. They were young men sharing accommodation and had both been at public school, where stripping off for swimming etc. was the convention.”

Lawrence first mentions de Chroustchoff in a letter of 22 November 1915 as “a young Russian anthropologist and bibliophile”, and “a “possible” for the new Rananim” (7L 78).[6] Lawrence invited him and Cecil Gray to visit him in Cornwall; concerning this visit, Natasha’s position was that:

‘exactly when, where and what occurred I cannot say. Having lived in Munich as a boy he could well have been involved in the singing of German songs – I can imagine that. He would have jumped at the chance to get out of London. He relished remote country areas, was a great walker and was also keenly interested in obscure languages. He owned Cornish dictionaries and maps. And of course he married a Cornish woman.’

According to Mark Kinkead-Weekes Boris visited the Lawrences in July 1917, and they remained in contact until 1928.[7]

Natasha observed:

‘So, Boris would have been in his mid/late 20s when he knew Lawrence; his English was perfect – he had no foreign accent, just sounded like an upper class Englishman of the time; and his manners were faultless. He was fairly small (around 5’8”) and slim, with dark hair, and very robust – he walked, bicycled, climbed, drank, cooked and caroused. His personality was unusual, magnetic even … Nevertheless he slips through the literature of, and about, the period like a Will o’ the Wisp: now you see him, now you don’t. My father was not himself a creative individual in the typical sense, but he had a personal charisma that attracted those who were. His background, the depth and extent of his knowledge (especially of esoteric “niche” subjects), his appearance and charm seemed to be magnetic to anyone who was not satisfied with conventionality.’

However, he gets bare mentions in the biographies of Warlock/Heseltine. He is not mentioned by Cecil Gray in his 1934 book on Peter Warlock: A Memoir of Philip Heseltine, and in Brian Collins’ 1996 Peter Warlock: The Composer there are just two short footnote mentions of de Chroustchoff as a friend of Heseltine married to Phyllis Crocker.[8]

Boris did not keep in touch with Lawrence after the latter left England for the last time in 1928, and later fell out with Philip Heseltine. He married a Cornish artist’s model, Phyllis Vipond Crocker, who had been living in a cottage just outside Zennor during de Chroustchoff’s visit (Heseltine, incidentally, was also attracted to her), but they did not marry until 1921; this was after Phyllis’s mother moved to London with her three daughters in order to live with and eventually marry the antiquarian book seller Irving Davis. Later in 1921 Phyllis gave birth to a son, Igor, who died in 2015. Boris became an antiquarian bookdealer with a shop in Bloomsbury (The Salamander Bookshop). After Boris and Phyllis’s marriage broke down, Boris married Ida Vera King, a young librarian living independently in London. In 1940 they moved to the Black Mountains of Breconshire to escape the Blitz, where Natasha was born just after the War had ended. Boris died in Oxford in 1969 aged 77.

After this overview of Boris’s life, Natasha turned to Boris’s collection of tribal art. She spoke on Zoom with the surviving collection arranged behind her, and shared photographs of the collection as it had been arranged in her father’s room in Oxford c. 1912.

Unfortunately for those interested in the connection to Women in Love, there is no surviving sculpture – or photograph of a sculpture – of a parturient woman. Helen Anderson, a curator of the African collection at the British Museum, confirms Natasha’s opinion that African sculptures of women in childbirth are in fact extremely rare: “You are correct that African representations of women in the act of childbirth are indeed rare. Objects and rituals around fertility and motherhood are prevalent in cultural groups across the Continent, but images of parturient women are not.”[9]Anderson did ascertain that Boris had lent items to an exhibition of “Art from the Guinea Coast” held at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford in 1965; the museum’s report in 1966 notes that “In addition to the Museum’s own collections which formed the bulk of the display the Museum is grateful for loans from the Federal Government of Nigeria, the Oni of Ife, the Oba of Benin, the Dagacin Jebba Gungu, the Trustees of the British Museum, Mr. Hugh Nevins, and Mr. Boris de Chroustchoff, whose generosity made it possible to see the history of West African art in much greater depth than would otherwise have been possible.” However, the catalogue to this exhibition does not picture or describe any parturient women.

Natasha makes the alternative speculation that the inspiration for Lawrence’s “fetish”, rather than being an African sculpture, may at least in part have been an Aztec-style sculpture (possibly pre-Columbian, more probably carved or re-carved in the nineteenth century) which was discovered in 1899 and:

‘became the subject of a great deal of interest and speculation by a wide range of scholars and intellectuals throughout the early part of the twentieth century. My father, as someone with an ethnographic background, would doubtless have been aware of it and it’s very possible he could have shown Lawrence an image. I can’t provide any evidence, but he was interested in pre-Columbian art and archaeology and I have several of his books on the subject … It could well have been something to which my father (or someone else) drew Lawrence’s attention, and which made an impression upon him.’[10]

It is worth noting, however, that the “fetish” in Women in Love does not as obviously as the Aztec-style one represent a woman giving birth; “her abdomen stuck out”, but evidently no part of a baby is visible, since Libnikov feels the need to explain to Gerald that “she was sitting in childbirth” (WL 74). Moreover the novel’s figure is “wooden” (WL: 79) and of a “negro woman” with “hands gripping the ends of the band, above her breast” (78). It is possible that an (atypical) sculpture of this description existed in Boris’s collection, was known to Lawrence, and has been lost. However, if and insofar as Lawrence invented Halliday’s “fetish”, the fact of his choosing to do so – and therefore to associate not just Africa but childbirth with “ultimate physical consciousness” (79) – would itself be of interest.

Finally, Natasha clarified that she only became aware of her father’s former connection to Lawrence when Lady Chatterley’s Lover became a sensation at its unbanning in 1960. This rekindled Boris’s own interest in Lawrence; he read The Plumed Serpent and Harry T. Moore’s 1954 biography The Intelligent Heart: The Story of D. H. Lawrence, in the latter finding a reference to Libidnikov that did not mention himself. Wishing it to be known that the character was based on him, he wrote to Moore as follows:[11]

May 13th 1964

Dear Professor Moore,

On page 239 of the English edition of “The Intelligent Heart” you mention Maxim Libidnikov and suggest that “this may be partly a portrait of Koteliansky.”

No, it is intended to be a portrait of myself, B.de Chroustchoff; a little whimsy on the part of DHL.

I was a very old friend of Philip Heseltine from Oxford days and shared various flats with him, and it was through him that I met DHL in 1915 during the “Rainbow” crisis and saw him on and off until his last visit to England.

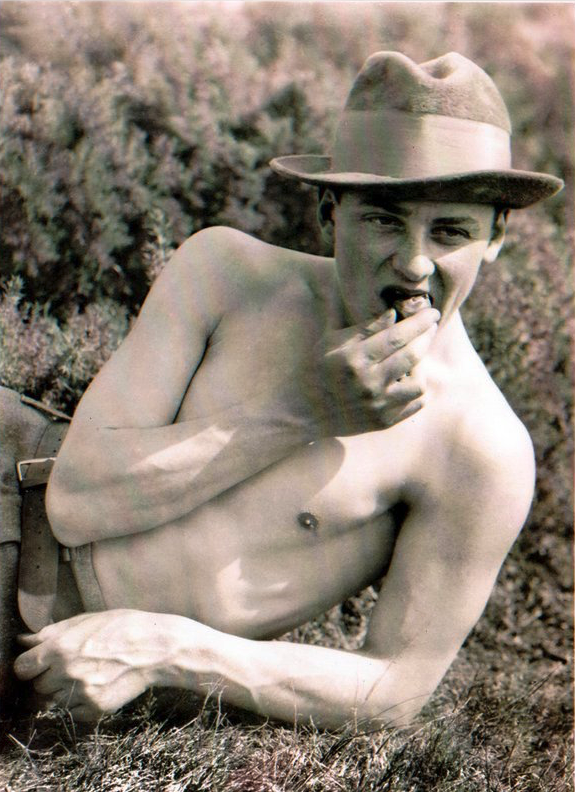

Incidentally I have a photo of “Pussum” that has never been published and I doubt whether there is another in existence. It is contemporary with “Women in Love.” If you would like to see it do not hesitate to ask me.

I knew DHL and Frieda very well, and also Orioli and various other personages who were about at that time. DHL and I got on very well together and I don’t think he abused me behind my back very much. But at one time he wrote some rather peevish letters to Cecil Gray bemoaning the fact that (in his usual phraseology) Gray “loved” me more than he loved DHL, and that it was a bad thing and no good would come of it. The letters were sold by Gray to some bookseller who decently remarked at the time that it seemed unfriendly to sell letters wherein a friend of his was mentioned in abusive terms just for the sake of gain when he (Gray) was perfectly well off.

Frieda of course was always talking about her children and we would speak in German about her family the von Richtofens. She was delighted to hear that I knew a cousin of hers, a von Richtofen who was in the same college as me at Oxford. DHL used to come to my house for a meal occasionally and one day I invited Cecil Gray who was on the point of marrying a Russian girl who was daughter of Countess Brassov, the morganatic wife of Grand Duke Michael, brother of Czar Nicholas II.[12]The Lawrences arrived first and when I told DHL that Gray was expected and he was going to marry a Russian princess (that is what this lady was known as amongst her friends) he flew into a rage and squeaked petulantly about it, saying that Gray should not do such a thing. Everyone of course realised that he felt outdone by Gray marrying a “Princess” whereas he himself had only succeeded in marrying an ordinary Baroness.

The dinner party was not a success because DHL resented the fact that some of the dishes were unfamiliar to him. The climax came when, for dessert, Chinese lychees were served in some rather remarkable peacock blue Syrian blown-glass bowls [of mine] which provided a particularly delightful colour scheme. His rage was quite extraordinary because he had never tasted, or heard of, lychees and he could not bottle up his extreme annoyance at this.

I am just telling you this because the Lawrence of the biographies and the real Lawrence are quite different people. You will remember how he behaved over the little bitch [dog] that got pregnant without his permission and “betrayed” him.

For instance, at that time I had a collection of African sculptures and these are the things that Lawrence mentions as “wooden figures”. And the Indian servant was Nazim Khan who originally was a retainer of Shahid Suhrawardy – a friend of Heseltine’s and mine at Oxford – a patrician Indian Moslem from what is now called Pakistan.[13] When Suhrawardy went away on a journey he asked us to look after Nazim and have him as a servant, saying that he only needed a bed, a little vegetable curry and an occasional shilling.

Accordingly in The Priest of Love (1974) Moore writes: “Boris de Croustchoff, a friend of Heseltine’s, has told the present writer that he was himself the model for Libidnikov”, and that he described himself as “a Russian bibliographer and London bohemian”.[14] Moore had also included several photos taken and contributed by (though not attributed to) Boris in his 1966 D.H. Lawrence and his World (Thames and Hudson), as Boris mentions in the following letter to Ken Russell, written when the latter was planning his film of Women in Love:[15]

Dec. 29th 1968

Dear Mr Russell,

I have heard that you are making a film of “Women in Love” by D. H. Lawrence.

This book of Lawrence’s has always been of particular interest to me because I was one of the characters in it, viz. “Maxim Libidnikov”.

Also I was a very close friend of “Halliday” (Philip Heseltine) and “Minette” – or “Pussum” (Puma, later to be Heseltine’s wife), and various other people mentioned in the book. In fact I even know the real name of the Indian servant who looked after Heseltine and me when we were sharing a flat in Chelsea.

No doubt you know the book “Lawrence and His Circle” by Harry T. Moore. I provided some of the photographs reproduced in this book.

Philip Heseltine was at Oxford with me (just before and at the beginning of the first world war) and afterwards we shared flats in various parts of London. I knew Lawrence very well too and am probably the only remaining member of that particular circle of which Lawrence writes in “Women in Love”.

Naturally I am very interested in the film you are making, and knowing that you are very keen on accuracy in your films I feel you might like to get in contact with me. It’s amazing that I can even remember the shade of “Pussum”’s face powder as I often had to buy it for her when she was too lazy to get out of bed and go and buy it herself. Also the African figures mentioned in the book belonged to me. Lawrence had never seen anything like them before he saw my collection.

Yours sincerely,

Boris de Chroustchoff

Further confirmation of Boris being the inspiration for Women in Love’s “young Russian” can be found in the 1962 memoirs of the journalist Michael Davidson (1897-1975), who knew both Boris and Heseltine.[16] He also mentions that Boris inspired the character of Ivan de Czelten in the 1925 novel Harvest in Poland by the diplomat, essayist, novelist, and contemporary of Boris at Oxford, Geoffrey Pomeroy Dennis (1892-1963). As Natasha confirms, de Czelten has in common with her father his Russian ancestry and childhood, love of climbing, and passion for food. The narrator, Emanuel, describes his physique as ‘small and elfin’, which accords with Lawrence’s perception of Libinikov. Moreoever:

\the most famous thing about Czelten, and the centre of his own loves, was his collection of gods and idols. His room – mantelpiece, tables, walls – was crowded with fallen deities from Africa, Asia, the Americas and the Pacific Isles: a really valuable collection. My own favourite was a wooden monstrosity, some three feet high, gauntly enthroned in the middle of the mantelpiece, whose face wore a thin leer … It was indeed in connection with his idol worship, his whoring after strange gods, that Czelten, before I knew him well, first came to my rooms’ [17]

Lawrence read this novel in 1925 (Letters V 256). Boris’s copy is inscribed by the author as “Emmanuel” to “Ivan de Czelten”:

Interest in the origin of the character of Libidnikov, in what has consistently been received as a roman à clef, has doubtless been dampened by the fact that the collection of African figures does not appear to belong to him (despite the fact that it is he who explains the “fetish” to Gerald, and says of the figures in general that “they are very good”) (WL 74). It is Halliday who invites Gerald to stay the night at the flat (“I always put people up”), and Libidnikov’s suggestion of staying the night in Halliday’s room is at least consistent with him being another guest rather than a co-resident. Prior to becoming sharply aware of Boris de Chroustchoff, I pursued the significance of this somewhat enigmatic character in terms of his ethnicity. Compelling though the topic of Lawrence’s relations with Russians and Russia is, and curiously stressed though Russianness is by repeated mention and the flamboyance of the name, this character’s nationality is in fact largely contingent. Libidnikov’s significance, rather, lies in the fact that the man who inspired Lawrence to create him also introduced him to objects which helped to develop his conceptions of Africa, of its art, of “ultimate physical consciousness” (79), and, potentially, also of childbirth. In so doing he inspired one of the most vivid responses to traditional art to be found in British literary modernism.

[1] Catherine Brown, ‘“The Young Russian”: Lawrence, Libidnikov and London’s Russians in the First World War’, JDHLS 5.2 (2019), 103-123.

[2] Natasha de Chroustchoff read anthropology at University College London and subsequently worked for a period with an archaeologist before pursuing another career.

[3]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Kardovsky,_Portrait_of_Marya_Anastasievna_Chroustchva.jpg

[4] http://england.prm.ox.ac.uk/noajax-individualsb1ff.html?i_l=D&i_id=248.

[5] Cecil Gray, Musical Chairs or Between Two Stools: Being the Life and Memoirs of Cecil Gray (London: 1948), 291.

[6] Mark Kinkead-Weekes, D.H. Lawrence: Triumph to Exile, 1912-1922 (Cambridge

University Press, 1996), 289.

[7] Ibid., 386, 816.

[8] Brian Collins, Peter Warlock: The Composer (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1996), 80, 118.

[9] See also endnote 74:13 (WL: 538).

[10] For more information on this sculpture see https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/artefacts/birthing-figure.

[11] Letter quoted courtesy of Natasha de Chroustchoff.

[12] https://www.geni.com/people/Natalie-Tata-Majolier/6000000011705488191

[13] https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw87340/Hasan-Shahid-Suhrawardy-Philip-Arnold-Heseltine-Peter-Warlock-DH-Lawrence

[14] Harry T. Moore, The Priest of Love (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1974), 286.

[15] Letter quoted courtesy of Natasha de Chroustchoff.

[16] The World, the Flesh and Myself (London: Gay Men’s Press, 1985), 139. Thanks are here recorded to Liam Osterman for bringing this reference to my attention.

[17] Geoffrey Pomeroy Dennis, Harvest in Poland (London: Heinemann, 1925), 70.