The following is a pre-edited version of a review which appears in DH Lawrence Review (the DH Lawrence Journal of North America), February 2019.

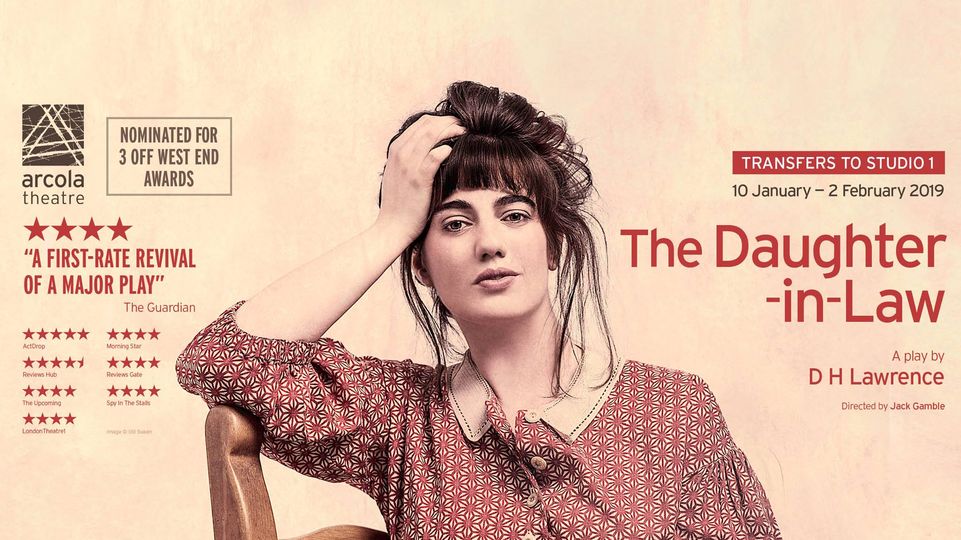

The Daughter-in-Law, Arcola Theatre, Dalston, East London, UK, director Jack Gamble

10thJanuary – 2ndFebruary 2019; revival of production which ran at the Arcola Theatre until 23rdJune 2018

Cast:

Luther Gascoyne Matthew Barker

Mrs Purdy Tessa Bell-Briggs

Joe Gascoyne Matthew Biddulph

Minnie Gascoyne Ellie Nunn

Mrs Gascoyne Veronica Roberts

It is an indication of the historic lack of success of Lawrence’s plays that Lawrencians must celebrate the fact that one of his plays has not only been produced in London, but that the production is having a sell-out revival in a larger auditorium of the same theatre half a year later. James Moran’s 2015 monograph The Theatre of D.H. Lawrence: Dramatic Modernist and Theatrical Innovator makes clear how beset by misfortune Lawrence’s plays have been from the outset (and why therefore only The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd and Davidwere performed in his lifetime). Hueffer had wanted to help the early plays into performance, but lost two of Lawrence’s manuscripts. The Irish Marxist Douglas Goldring favoured Touch and Go, until he and Lawrence fell out over politics. Virginia Mackenzie wanted to produce Lawrence plays at Nottingham’s Grand Theatre, but her theatre folded. The British and Swedish productions of a Lawrence play in the late thirties were in fact of The Daughter-in-Law as rewritten (as My Son’s My Son) by novelist Walter Greenwood, with a more resolved conclusion which was praised above Lawrence’s. Ultimately, of course, the problem was that Lawrence was writing in the nineteen-teens rather than the sixties, when, notwithstanding the simultaneous development of theatrical modernism, naturalism finally broke its way out of the novel and onto the English stage. The Fight for Barbara and The Daughter-in-Law premiered eleven years after Look Back in Anger, but the latter was clearly influenced by the former, from the plot down to the protagonist’s name (Jimmy).

After a brief period in the sun in the late nineteen-sixties and early seventies, Lawrence’s plays again disappeared from the British stage. When, as part of the 14thInternational DH Lawrence conference at London in 2017, The Merry-go-Round was performed at the RADA Studios, this was – as far as I was able to ascertain – only the second production of the play since its premiere under Peter Gill at the Royal Court Theatre, London, in 1973.

Yet the 2018-19 production of the Arcola Theatre’s The Daughter-in-Lawis not an isolated incident in recent history. The Daughter-in-Law was performed in 2013 at The Crucible in Sheffield, and the following spring at RADA in London. That autumn The Widowing of Mrs Holroydran at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond, and in 2015-16 Ben Power’s mash-up of A Collier’s Friday Night,The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd and The Daughter-in-Law into the composite play Husbands and Sonsran with considerable success at the National Theatre in London. In January 2019, a former editor of the UK DH Lawrence Society Newsletter, David Brock, founded a group for reading Lawrence’s dramas – ‘The Lawrence Players’ – in Chapel-en-le-Frith in Derbyshire. One can say that, over the last six years, Lawrence’s plays have had a modest, but historically-striking, revival in the UK.

The producer who invited me on to the BBC Radio 4 arts magazine programme ‘Front Row’ to discuss the recent production of The Daughter-in-Lawprepped me with the question: ‘why are Lawrence’s plays having such a moment on the London stage?’ I was grateful for the notice, since I didn’t have a convincing answer immediately to hand, but in the interim I reflected as follows. In 2008 there was a ‘Credit Crunch’ in the UK and internationally. The UK went into recession, and in response the post-2010 government imposed austerity, cut benefits, and enacted fiscal and monetary policies which in practice enriched those at the top of the income scale.

The resultant increasing inequality of wealth was, according to director Jack Gamble, one of the things that made him interested in The Daughter-in-Law. Luther mentions that the manager Frazer earns ‘twelve hundred a year’. This is $123,000 in today’s money. Luther’s dayman’s wage is seven shillings per day, $9,300 in today’s money. A 13-fold wage differential between senior management and the lowest paid in a company now seems low. Since Lawrence’s time, and especially since the Credit Crunch, that ratio has multiplied many times over. As a result of anti-trade-union legislation in the UK from the 1980s onwards, the chance of industry-wide strikes such as The Daughter-in-Lawdepicts has been much lowered. But the awareness, on the part of many who are on average or below-average pay, that there are enormous differences of wealth and reward for effort in this country, has produced considerable anger. Modest terraced houses such as the Lawrence birthplace on Victoria Street in Eastwood, or the Breach House on Garden Road, are now affordable only by the middle classes. The young, and those at the lower end of the income scale, rent single rooms in shared houses. Such people amongst the audience members may have particularly appreciated Mrs Purdy’s line: ‘It’s a wonder they let us live on the face o’ th’earth at all – it’s a wonder we don’t have to fly up i’ th’air like birds.’

Admittedly, such anger is not the main subject of The Daughter-in-Law; its presence in Luther and Joe, and its absence in Minnie and Mrs Gascoigne, is one among several of their tensions. But in the central relationship of Minnie and Luther, wealth differential is a crucial factor – which is why the two of them, in their effort to come together, destroy it: she by converting it into art; he by converting it into fire.

Another, related, context concerns a narrowing of social opportunity, and the increasing centralisation of the UK on London. The heyday of Lawrence’s UK reputation, in the 1950s and 60s, coincided with a considerable opening of the universities, professions, media, and Parliament, to working-class men with regional accents. Since the 1980s, this process has partially gone into reverse – a trend which culminated in the 2015 government led by David Cameron and fellow Old Boys of Eton College. Now, more than at any point in the last four decades, trainee actors are unlikely to come from poorer backgrounds, or to speak with anything other than received pronunciation. This is why a majority of the cast of the current production (Joe Biddulph’s Joe Gascoigne notably excepted) have had to learn Nottinghamshire accents. Lawrence must have anticipated that the dialect of his mining plays might be greeted on the London stage – if they ever indeed reached it – with titters of surprise and wonderment. The current production does provoke such; after all, Nottinghamshire accents are as unfamiliar in London and the London-based media as at any point in the last forty years. The regions, which were forgotten as London increasingly centralised wealth and power in itself, strongly asserted their independence in the Brexit referendum of 2016. That reminder to London that the rest of England exists, and does not think like it, might also provide an impetus to revisit Lawrence’s Nottinghamshire plays, quite independently of their own political positions.

Finally, I think that one further factor may underlie the revival of interest in Lawrence’s plays. The MeToo movement, which started in 2017 – and its excesses, and reasonable and unreasonable criticisms of it – has stimulated an appetite for art which addresses the complexity of the relations between the sexes. This production of The Daughter-in-Lawwill in fact have done much to undermine the widespread perception amongst older people (not my students, who are too young to know anything of the feminist critique of Lawrence, and not the significantly older, who were sceptical of that backlash when it came) that Lawrence is a misogynist. The play is named for a woman, as are many of his plays. Moran notes that between 1909 and 1913 56% of Lawrence’s named dramatic roles are female – good by the standards of any time;The Fight for Barbaraand The Merry-Go-Roundhave equal male and female parts; otherwise, women dominate. Minnie and Mrs Holroyd are the play’s protagonists and antagonists; the men are either dead, absent, or literally or metaphorically disabled. The critique of the mother as crippling the development of her younger sons is made not by the son himself, as in Sons and Lovers, but by her daughter-in-law.

The play retains the audience’s sympathy for Minnie through even her harshest attacks on her husband, in part because of its constant insinuation of her difficult upbringing: her early loss of her parents, her vexed if unexplained relationship with her uncle, and her heavy reliance on her former employer. Moreover, in this play of people failing to get very far – Mrs Gascoigne grimly holding onto what she has left of her family; Mrs Purdy striving merely to keep herself and simple daughter above water; Luther working without ambition; Joe drifting – Minnie represents what in The Rainbow is called the widening circle. She has known, and can at any time access, city life. She brings a refined taste in furniture and art to a mining community that does not know how to appreciate them. During one of the after-show talks of the current production, Veronica Roberts, who played Mrs Gascoigne, said that one thing she had come to understand about mining life from her involvement in the play was that the women were the bearers of culture, not least because they remained above ground. They had their own deal of work to do, but they remained in the light, and as such might read, or could look out of the window to the wider world beyond. Minnie is the play’sKulturträger(it would have required considerable intelligence, as a working class woman, to be selected as a governess by a middle-class family, which usually wanted an impoverished member of the higher classes to impart class to its children). Finally, Minnie has the will to fight her way – albeit indirectly and often perversely – to a closer relationship to her husband. Such vision and such force –powerfully rendered by Ellie Nunn – excuses much.

The mother-in-law, attractively played by Veronica Roberts, also attracts sympathetic respect – not least in her wittily epigrammatic assertions of the problems that men bring to women:

Children they are, these men, but my word, they’re revengeful children. Children men is a’ the days o’ their lives. But they’re master of us women when their dander’s up, an’ they pay us back double an’ treble – they do

it’s risky work, handlin’ men, my lass, an’ niver thee pray for sons

An’ so, tha’lt reap trouble by the peck, an’ sorrow by the bushel For when a woman builds her life on men, either husband or sons, she builds on summat as sooner or later brings the house down crash on her head – yi, she does.

a childt is a troublesome pleasure to a woman, but a man’s a trouble pure an’ simple.

Lines such as these recall Anaïs Nin’s 1932 assertion that Lawrence’s writings represented ‘the first time that a man has so wholly and completely expressed a woman accurately’.

Which is not, of course, to say that the contents of these assertions are unequivocally endorsed. This is not so much because contrastive experience on the part of men is presented with anything like equal force in the play (it is not, and the final tableaux of Luther weeping in Minnie’s arms supports Mrs Gascoigne’s assertion that men remain children), but because Mrs Gascoigne is partly speaking in self-justification shortly after her daughter-in-law’s attack. Moreover, as the former herself admits, both of them are ultimately orientated towards men: ‘Th’world is made o’ men for me, lass – there’s only the men for me. An’ tha’rt similar’. Mrs Gascoigne was not envisaging a future world in which women would make their way in fields of work dominated by men, and would discover the disadvantages of femininity. But her implication that one way to become less vulnerable to being hurt by men is to become less psychologically reliant on, and orientated towards, them, does perhaps give a hint to the MeToo movement – to look for sisterhood in professional life, and to become less concerned with what men think of women. Minnie’s claim that ‘I’d rather have had a husband who knocked me about, than a husband who was good to me because he belonged to his mother’ is on its face unassimilable in today’s discourse. But, quite apart from the fact that it is spoken in anger, it is an assertion that emotional harm can be at least as destructive as physical. This perception was recently enshrined in UK law, when the definition of domestic violence expanded to include emotional violence (albeit not of the passive kind of which Minnie accuses Luther).

Yet the women in this play are not innocent; if anything the men (skilfully played as relative simpletons by Matthew Barker and Matthew Biddulph) more deserve that characterisation. The play presents the complexities as well as tensions of sexual relationships, especially as played out in a limited physical space and a situation of financial strain – but with particular sympathy to the problems of the women. In all these respects, this is a play that is ripe for modern Britain.

The auditoria (both the larger one of its current production, and the smaller one used last year) resemble mine-shafts: windowless, black-painted theatres in the round. The rattle of mine machinery between the acts was used to emphasise this sense. Even the seats were cramped: audience and characters alike were thrown hugger-mugger – and they had to get on. If anything, this was slightly overdone. As mentioned above, the Lawrence houses in Eastwood are today dignified middle-class dwellings. The play set abolished away any concept of space: there was no garden in which characters could go to cool off, and no windows from which the women might see the widening world beyond.

Yet the humour of the play was allowed to breathe, and even accorded the liberty of adding an ‘h’ to words beginning with a vowel – such as ‘a haccident’. The apercus of Mrs Gascoigne, and phrases of Mrs Purdy (such as ‘my long thing’) reliably elicited a laugh. The largest of these was produced by: ‘Marriage is like a mouse trap, for either man or woman. You soon come to ter th’ end o’ th’ cheese’. Of course in modern Britain, where there are minimal social, legal or financial inducements to get married, fewer people than ever do so, and the ‘trap’ is relatively easily escapable, the laughter that this line evokes is less deeply felt than it would have been had the play been produced in Lawrence’s lifetime. Nonetheless, across the hundred-and-six years that separated us from the play, the laughter was one of recognition.

So here we were, in a hipster theatre in the East End of a metropolis, which, like the rest of the country, may be about to crash into recession because of a Brexit voted for by many of those in Eastwood, meditating on a provincial play written on Lake Garda concerning the widening circle, and the limitations to that widening. I was reminded of the thoughts that I wrote down at the end the Lawrence and War Poetry Day run by the UK Lawrence Society last June:

Sitting in the garden of the Breach House, sipping Ceylon tea and looking at the rhubarb and the red bricks, the green paint, the Gothic gable, the lawn, the neighbours’ washing, the Country of my Heart, it strikes me how English Lawrence was and how unEnglished he was to become. Not not English but not only English, his circle widening, just as official Englishness was constricting round the trigger of a gun. London, Cornwall, England were too narrow for his unEnglishness, which circumnavigated the world; the sun never set on it. International war was unthinkable – a nightmare of drone-like-remoteness. Meanwhile, over my tea, I recall the George flag filling the bow window of a house on Walker Street. [9.6.18]